Полная версия:

Road Brothers

Copyright

HarperVoyager

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in ebook in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2017

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2017

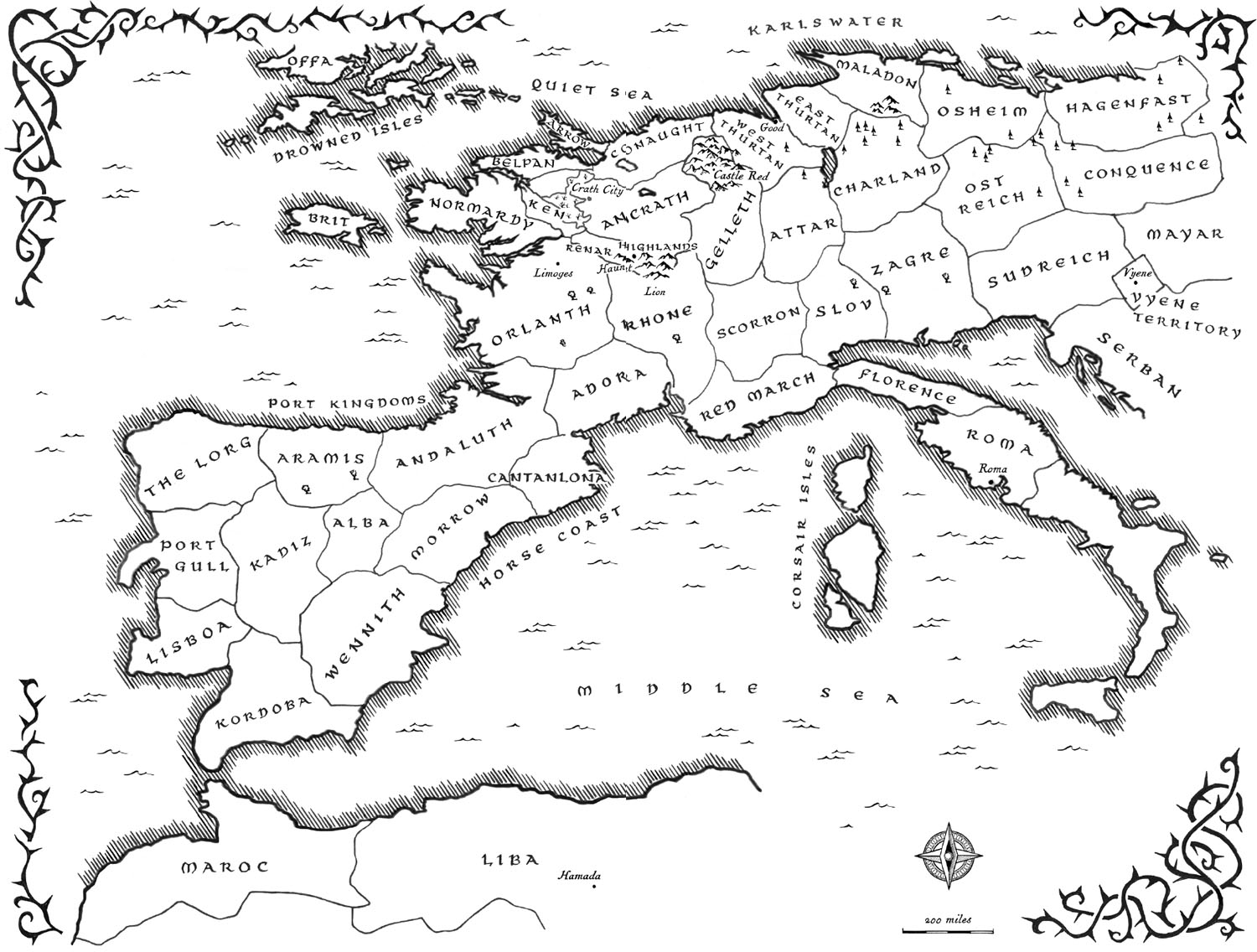

Map © Andrew Ashton

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Jacket illustration © Kim Kincaid

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These works are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008221386

Ebook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780008221393

Version: 2017-10-04

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

Introduction

A Rescue

Sleeping Beauty

Bad Seed

The Nature of the Beast

The Weight of Command

Select Mode

Mercy

A Good Name

Choices

No other Troy

The Secret

Escape

Know Thyself

Three is the Charm

Acknowledgements

Also by Mark Lawrence

About the Author

About the Publisher

Map

Introduction

I learned most of what I know about writing from writing short stories. They’re a great place to practise the art. They are also a fine means by which to revisit a character or a world, illuminating a corner of the original tale that perhaps deserves more attention. In addition, they can be used to look back over the years, allowing us to see how our heroes and villains … well mainly villains if we’re honest … came to be where we found them and what shaped them along the way.

The stories in this anthology were written over the space of a few years, mostly for other projects. They offer a mix of murder, mayhem, pathos, and philosophy, and stand on their own without the need to have read the books that inspired them. The events occur before or around the edges of those described in the Broken Empire trilogy and will contain a variety of spoilers.

I hope you’ll enjoy dipping into the lives of Jorg and his brothers one more time. It was a grand tale and I was sorry to leave it behind.

Mark Lawrence

Bristol, 2017

Oh, and I’ve added a brief footnote at the end of each story … because I wanted to!

A Rescue

‘I spent a year hunting down the men who burned my home. I followed them across three nations.’

‘I see.’ The old man laid down his quill and looked up across the desk at Makin.

Makin returned the stare. The king’s man had a long white beard, no wider than his narrow chin and reaching down across his chest to coil on the desk before him. He’d asked no question but Makin felt the need to answer.

‘I wanted them to pay for the lives of my wife and my child.’ Even now the anger rose in him, a sharpness twitching his hands towards violence, a yammering in his ears that made him want to shout.

‘And did it help?’ Lundist studied him with dark eyes.

The guards had told Makin the man had journeyed from the Utter East and King Olidan had hired him to tutor his children, but it seemed his duties extended further than that.

‘Did it help?’ Makin tried to keep the snarl from his voice.

‘Yes.’ Lundist set his hands before him, the tips of his long fingers meeting in front of his chest. ‘Did taking your revenge ease your pain?’

‘No.’ When he took to his bed, when he closed his eyes, it was blue sky Makin saw, the blue line of sky he had watched from the ditch he had lain in, run through, bleeding out his lifeblood. A line of china blue fringed with grass and weeds, black against the brightness of the day. The voices would return to him – the harsh cries of the footmen set to chase down his household. The crackle of the flames finding the roof. Cerys hid from the fire as her mother had told her to. A brave girl, three years in the world. She hid well and no one found her, save the smoke, strangling her beneath her bed before the flames began their feast.

‘… your father.’

‘Your pardon?’ Makin became aware that Lundist was speaking again.

‘The captain of the guard accepted you for wall duty because I know your father has ties with the Ancrath family,’ Lundist said.

‘I thought the test …’

‘It was important to know that you can fight – and your sword skills are very impressive – but to serve within the castle there must be trust, and that means family. You are the third son of Arkland Bortha, Lord of Trent, a region that one might cover a fair portion of with the king’s tablecloth. You yourself are landless. A widower at one and twenty.’

‘I see.’ Makin nodded. He had disarmed four of Sir Grehem’s men when they came at him. Several sported large bruises the next day although the swords had been wooden.

‘The men don’t like you, Makin. Did you know that?’ Lundist peered up from the notes before him. ‘It is said that you are not an easy man to get along with.’

Makin forced the scowl from his face. ‘I used to be good at making friends.’

‘You are …’ Lundist traced the passage with his finger, ‘a difficult man, given to black moods, prone to violence.’

Makin shrugged. It wasn’t untrue. He wondered where he would go when Lundist dismissed him from the guard.

‘Fortunately,’ Lundist continued, ‘King Olidan considers such qualities to be a price worth paying to have in his employ men who excel at taking lives when he commands it, or in defence of what he owns. You’re to be put on general castle duty on a permanent basis.’

Makin pursed his lips, unsure of how he felt. Taking service with the king had seemed to be what he needed after his long and bloody year. Setting down roots again. Service, duty, renewed purpose, after his losses had set him adrift for so long. But just now, when he had thought himself cut loose once more, bound for the loneliness of the road, he had, for a moment, welcomed it.

Makin stood, pushing back the chair that Lundist had directed him to. ‘I will attempt to live up to the trust that’s been placed in me.’ He thought of the ditch. Cerys had had faith in him, a child’s blind faith. Nessa had had faith, in him, in his word, in God, in justice … and her trust had seen her pinned to the ground by a spear in the cornfield behind her home. He saw again the blue strip of sky.

Lundist bent to his ledger, quill scratching across parchment.

As Makin turned to go, the tutor spoke again. ‘The need for vengeance feels like a hunger, but there is no sating it. Instead it consumes the man that feeds it. Vengeance is taking from the world. The only cure is to give.’

Makin didn’t trust himself to speak and instead kept his jaw locked tight. What did a dried-up old scribe know of the hurts he’d suffered?

‘There’s a gap between youth and age that words can’t cross,’ Lundist said. He sounded sad. ‘Go in peace, Makin. Serve your king.’

‘The Healing Hall is on fire!’ A guardsman burst through the door into the barracks.

‘What?’ Makin rolled to his feet from the bunk, sword in his hand. He’d heard the man’s words. Saying ‘what’ was just a reflex, buying time to process the information. He glanced at the blade in his grasp. An edge would rarely help in fighting flames. ‘Are we under attack?’ No one would be mad enough to attack the Tall Castle, but on the other hand the queen and her two sons had been ambushed just a day from the capital. Only the older boy had survived, and barely.

‘The Healing Hall is on fire!’ The man repeated, looking around wildly. Makin recognized him as Aubrek, a new recruit: a big lad, second son of a landed knight and more used to village life than castles. ‘Fire!’ All along the barracks room men were tumbling from their beds, reaching for weapons.

Makin pushed past Aubrek and gazed out into the night. An orange glow lit the courtyard and on the far side tongues of flame flickered from the arched windows of the Healing Hall, licking the stonework above.

Castle-dwellers scurried in the shadows, shouts of alarm rang out, but the siege bell held its peace.

‘Fire!’ Makin roared. ‘Get buckets! Get to the East Well!’

Ignoring his own orders, Makin ran straight for the hall. It had once been the House of Or’s family church. When the Ancraths took the Tall Castle a hundred and twenty years previously they had built a second church, bigger and better, leaving the original for the treatment of the sick and injured. Or, more accurately, to repair their soldiers.

The heat brought Makin up short yards from the wall.

‘The Devil’s work!’ Friar Glenn’s voice just behind him.

Makin turned to see the squat friar, halted a few yards shy of his position, the firelight glaring on the baldness of his tonsure. ‘Is the boy in there?’

Friar Glenn stood, mesmerized by the flames. ‘Cleansed by fire …’

Makin grabbed him, taking two handfuls of his brown robe and heaving him to his toes. ‘The boy! Is Prince Jorg still in there?’ Last Makin heard the child had still been recuperating from the attack that had killed his mother and brother.

A wince of annoyance crossed the friar’s beatific expression. ‘He … may be.’

‘We need to get in there!’ The young prince had hidden in a hook-briar when the enemy had come for him a week earlier. He had sustained scores of deep wounds from the thorns and they had soured despite Friar Glenn’s frequent purging in the Healing Hall. He wouldn’t be getting out on his own.

‘The Devil’s in him: my prayers have made no impression on his fevers.’ The friar sank to his knees, hands clasped before him. ‘If God delivers Prince Jorg from the fire then—’

Makin took off, skirting around the building toward the small door at the rear that would once have given access to the choir loft. A nine-year-old boy in the grip of delirium would need more than prayers to escape the conflagration.

Cries rang out behind him but with the roar of the fire at the windows no meaning accompanied the shouts. Makin reached the door and took the iron handle, finding it hot in his grasp. At first it seemed that he was locked out, but with a roar of his own he heaved and found some give. The air sucked in through the gap he’d made, the flames within hungry for it. The door surrendered suddenly and a wind rushed past him into the old church. Smoke swirled in its wake, filling the corridor beyond.

Every animal fears fire. There are no exceptions. It’s death incarnate. Pain and death. And fear held Makin in the doorway, trapped there beneath the weight of it as the wind died around him. He didn’t know the boy. In the years Makin had served in King Olidan’s castle guard he had seen the young princes on maybe three occasions. It wasn’t his part to speak to them – merely to secure the perimeter. Yet here he stood now, at the hot heart of the matter.

Makin drew a breath and choked. No part of him wanted to venture inside. No one would condemn him for stepping back – and even if they did he had no friends within the castle, none whose opinion he cared about. Nothing bound him to his service but an empty promise and a vague sense of duty.

He took a step back. For a moment in place of swirling smoke he saw a line of brittle blue sky. Come morning this place would be blackened spars, fallen walls. Years ago, when they had lifted him from that ditch, more dead than alive, they had carried him past the ruins of his home. He hadn’t known then that Cerys lay within, beneath soot-black stones and stinking char.

Somehow Makin found himself inside the building, the air hot, suffocating, and thick with smoke around him. He couldn’t remember deciding to enter. Bent double he found he could just about breathe beneath the worst of the smoke, and with stinging, streaming eyes he staggered on.

A short corridor brought him to the great hall. Here the belly of the smoke lay higher, a dark and roiling ceiling that he would have to reach up to touch. Flames scaled the walls wherever a tapestry or panelling gave them a path. The crackling roar deafened him, the heat taking the tears from his eyes. A tapestry behind him, that had been smouldering when he passed it, burst into bright flames all along its length.

A number of pallets for the sick lined the room, many askew or overturned. Makin tried to draw breath to call for the prince but the air scorched his lungs and left him gasping. A moment later he was on his knees, though he had no intention to fall. ‘Prince Jorg …’ a whisper.

The heat pressed him to the flagstones like a great hand, sapping the strength from him, leaving each muscle limp. Makin knew that he would die there. ‘Cerys.’ His lips framed her name and he saw her, running through the meadow, blonde, mischievous, beautiful beyond any words at his disposal. For the first time in forever the vision wasn’t razor-edged with sorrow.

With his cheek pressed to the stone floor Makin saw the prince, also on the ground. Over by the great hearth one of the heaps of bedding from the fallen pallets had a face among its folds.

Makin crawled, the hands he put before him blistered and red. One bundle, missed in the smoke, proved to be a man, the friar’s muscular orderly, a fellow named Inch. A burning timber had fallen from above and blazed across his arm. The boy looked no more alive: white-faced, eyes closed, but the fire had no part of him. Makin snagged the boy’s leg and hauled him back across the hall.

Pulling the nine-year-old felt harder than dragging a fallen stallion. Makin gasped and scrabbled for purchase on the stones. The smoke ceiling now held just a few feet above the floor, dark and hot and murderous.

‘I …’ Makin heaved the boy and himself another yard. ‘Can’t …’ He slumped against the floor. Even the roar of the fire seemed distant now. If only the heat would let up he could sleep.

He felt them rather than saw them. Their presence to either side of him, luminous through the smoke. Nessa and Cerys, hands joined above him. He felt them as he had not since the day they died. Both had been absent from the burial. Cerys wasn’t there as her little casket of ash and bone was lowered, lily-covered into the cold ground. Nessa didn’t hear the choir sing for her, though Makin had paid their passage from Everan and selected her favourite hymns. Neither of them had watched when he killed the men who had led the assault. Those killings had left him dirty, further away from the lives he’d sought revenge for. Now though, both Nessa and Cerys stood beside him, silent, but watching, lending him strength.

‘They tell me you were black and smoking when you crawled from the Healing Hall.’ King Olidan watched Makin from his throne, eyes wintry beneath an iron crown.

‘I have no memory of it, highness.’ Makin’s first memory was of coughing his guts up in the barracks, with the burns across his back an agony beyond believing. The prince had been taken into Friar Glen’s care once more, hours earlier.

‘My son has no memory of it either,’ the king said. ‘He escaped the friar’s watch and ran for the woods, still delirious. Father Gomst says the prince’s fever broke some days after his recapture.’

‘I’m glad of it, highness.’ Makin tried not to move his shoulders despite the ache of his scars, only now ceasing to weep after weeks of healing.

‘It is my wish that Prince Jorg remain ignorant of your role, Makin.’

‘Yes, highness.’ Makin nodded.

‘I should say, Sir Makin.’ The king rose from his throne and descended the dais, footsteps echoing beneath the low ceiling of his throne room. ‘You are to be one of my table knights. Recognition of the risks you took in saving my son.’

‘My thanks, highness.’ Makin bowed his head.

‘Sir Grehem tells me you are a changed man, Sir Makin. The castle guard have taken you to their hearts. He says that you have many friends among them …’ King Olidan stood behind him, footsteps silent for a moment. ‘My son does not need friends, Sir Makin. He does not need to think he will be saved should ill befall him. He does not need debts.’ The king walked around Makin, his steps slow and even. They were of a height, both tall, both strong, the king a decade older. ‘Young Jorg burns around the hurt he has taken. He burns for revenge. It’s this singularity of purpose that a king requires, that my house has always nurtured. Thrones are not won by the weak. They are not kept except by men who are hard, cold, focused.’ King Olidan came front and centre once more, holding Makin’s gaze – and in his eyes Makin found more to fear than he had in the jaws of the fire. ‘Do we understand each other, Sir Makin?’

‘Yes, highness.’ Makin looked away.

‘You may go. See Sir Grehem about your new duties.’

‘Yes, highness.’ And Makin turned on his heel, starting the long retreat to the great doors.

He walked the whole way with the weight of King Olidan’s regard upon him. Once the doors were closed behind him, once he had walked to the grand stair, only then did Makin speak the words he couldn’t say to Olidan, words the king would never hear, however loud-spoken. ‘I didn’t save your son. He saved me.’

Returning to his duties, Makin knew that however long the child pursued his vengeance it would never fill him, never heal the wounds he had taken. The prince might grow to be as cold and dangerous as his father, but Makin would guard him, give him the time he needed, because in the end nothing would save the boy except his own moment in the doorway, with his own fire ahead and his own cowardice behind. Makin could tell him that of course – but there are many gaps in this world … and there are some that words can’t cross.

Footnote

Makin has always been an interesting character for me, a failed father-figure if you like. He should be Jorg’s moral touchstone but too often finds himself swept along by the force of Jorg’s personality and by the chaos/cruelty of the life he’s entangled in. We root for him to recover himself.

Sleeping Beauty

A kiss woke me. A cool kiss pulled me from the hot depths of my dreaming. Lips touched mine, and deep as I was, dark as I was, I knew her, and let her lead me.

‘Katherine?’ I spoke her name but made no sound. A whiteness left me blind. I closed my eyes just to see the dark. ‘Katherine?’ A whisper this time. Damn but my throat hurt.

I turned my head, finding it a ponderous thing, as if my muscles strove to turn the world around me whilst I remained without motion. A white ceiling rotated into white walls. A steel surface came into view, gleaming and stainless.

Now I knew something beyond her name. I knew white walls and a steel table. Where I was, who I was, were things yet to be discovered.

Jorg. The name felt right. It fitted my mouth and my person. Hard and direct.

I could see a sprawl of long black hair spread across the shining table, reaching from beneath my cheek, overhanging the edge. Had Katherine climbed it to deliver her kiss? My vision swam, my thoughts with it – was I drunk … or worse? I didn’t feel myself – I might not yet know who I was, but I knew enough to say that.

Images came and went, replacing the room. Names floated up from the back of my mind. Vyene. I had a barber cut my hair almost to the scalp when I left Vyene. I remembered the snip of his shears and the dark heap of my locks, tumbled across his tiled floor. Hakon had mocked me when I emerged cold-headed into the autumn chill.

Hakon? I tried to hang details upon the void beneath his name. Tall, lean … no more than twenty, his beard short and bound tight by an iron ring beneath his chin. ‘Jorg the Bald!’ he’d greeted me and fanned out his own golden mane across his shoulders, bright against wolfskins.

‘Watch your mouth.’ I’d said it without rancour. These Norse have little enough respect for royalty. Mind you neither do I. ‘Has my beauty fled me?’ I mocked sorrow. ‘Sometimes you have to make sacrifices in war, Hakon. I surrendered my lovely locks. Then I watched them burn. In the battle of man against lice I am the victor, whilst you, my friend, still crawl. I sacrificed one beauty for another. My own, in exchange for the cries of my enemies. They died by the thousand, in the fire.’

‘Lice don’t scream. They pop.’

I recalled the bristling of scalp beneath palm as I rubbed my head trying to find an answer to that one. I tried now to touch the hair spread out before me across the steel but found my hands restrained. I made to sit up but a strap across my chest held me down. Straining, I could see five more straps binding me to the table, running across my chest, stomach, hips, legs, and ankles. I wore nothing else. Tubes ran from glass bottles on a stand above me, down into the veins of my left wrist.

This room, this white and windowless chamber, had not been made by any people of the Broken Empire. No smith could have fashioned the table, and the plasteek tubes lay beyond the art of some king’s alchemist. I had woken out of time, led by dreams and a kiss to some den of the Builders.

The kiss! I flung my head to the other side, half-expecting to find Katherine standing there, silent beside the table. But no – only sterile white walls. Her scent lingered though. White musk, fainter than faint, but more real than dream.

Me, a table, a simple room of harsh angles, kept warm and light by some invisible artifice. The warmth enfolded me. My last memories had been of cold. Hakon and me trudging through the snow-bound forests of eastern Slov, a week out from Vyene. We picked our path between the pines where the ground lay clearest, leading our horses. Both of us huddled in our furs, me with only a hood and a quarter inch of hair to keep my head from freezing. Winter had fallen upon us, hard, early, and unannounced.

‘It’s buggery cold,’ I said unnecessarily, letting my breath plume before me.

‘Ha! In the true north we’d call this a valley spring.’ Hakon, frost in his beard, hands buried in leather mittens lined with fur.

‘Yes?’ I pushed through the pine branches, hearing them snap and the frost scatter down. ‘Then how come you look as cold as I feel?’

‘Ah.’ A grin cracked his wind-reddened cheeks. ‘In the north we stay by the hearth until summer.’