Полная версия:

Prince of Fools

PRINCE OF FOOLS

Book One of The Red Queen’s War

Mark Lawrence

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2014

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2014

Jacket layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Jacket illustration © Jason Chan

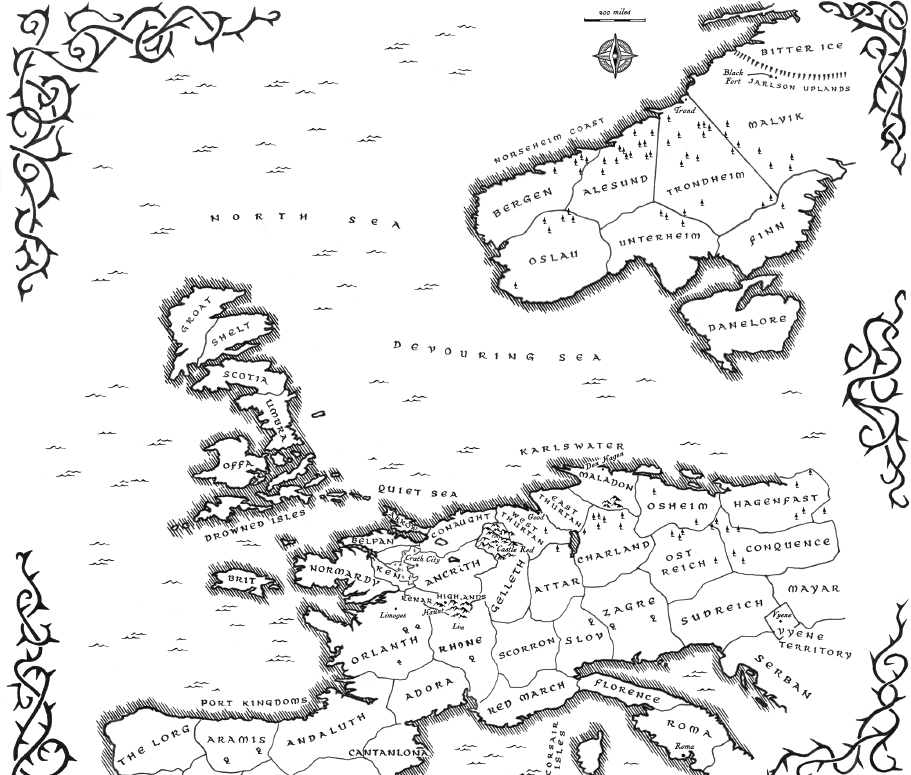

Map © Andrew Ashton

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007531530

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007531554

Version: 2017-05-31

Dedication

Dedicated to my daughter, Heather.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Mark Lawrence

About the Publisher

1

I’m a liar and a cheat and a coward, but I will never, ever, let a friend down. Unless of course not letting them down requires honesty, fair play, or bravery.

I’ve always found hitting a man from behind to be the best way to go about things. This can sometimes be accomplished by dint of a simple ruse. Classics such as, ‘What’s that over there?’ work surprisingly often, but for truly optimal results it’s best if the person doesn’t ever know you were there.

‘Ow! Jesu! What the hell did you do that for?’ Alain DeVeer turned, clamping his hand to the back of his head and bringing it away bloody.

When the person you hit doesn’t have the grace to fall over it’s generally best to have a back-up plan. I dropped what remained of the vase, turned and ran. In my mind he’d folded up with a pleasing ‘oofff’ and left me free to leave the mansion unobserved, stepping over his prone and senseless form on the way. Instead his senseless form was now chasing me down the hall bellowing for blood.

I crashed back through Lisa’s door and slammed it behind me, bracing myself for the impact.

‘What the hell?’ Lisa sat in the bed, silken sheets flowing off her nakedness like water.

‘Uh.’ Alain hammered into the door, jolting the air from my lungs and scraping my heels over the tiles. The trick is to never rush for the bolt. You’ll be fumbling for it and get a face full of opening door. Brace for the impact, when that’s done slam the bolt home while the other party is picking himself off the floor. Alain proved worryingly fast in getting back on his feet and I nearly got the doorhandle for breakfast despite my precautions.

‘Jal!’ Lisa was out of bed now, wearing nothing but the light and shade through the shutters. Stripes suited her. Sweeter than her elder sister, sharper than her younger sister. Even then I wanted her, even with her murderous brother held back by just an inch of oak and with my chances for escape evaporating by the moment.

I ran to the largest window and tore the shutters open. ‘Say sorry to your brother for me.’ I swung a leg over the casement. ‘Mistaken identity or something …’ The door started to shudder as Alain pounded the far side.

‘Alain?’ Lisa managed to look both furious with me and terrified at the same time.

I didn’t stop to reply but vaulted down into the bushes, which were thankfully the fragrant rather than thorny variety. Dropping into a thorn bush can lead to no end of grief.

Landing is always important. I do a lot of falling and it’s not how you start that matters so much as how you finish. In this instance, I finished concertinaed, heels to arse, chin to knees, half an azalea bush up my nose and all the air driven from my lungs, but with no bones broken. I fought my way out and limped toward the garden wall, gasping for breath and hoping the staff were too busy with pre-dawn chores to be poised and ready to hunt me down.

I took off, across the formal lawns, through the herb garden, cutting a straight path through all the little diamonds of sage, and triangles of thyme and whatnot. Somewhere back at the house a hound bayed, and that put the fear in me. I’m a good runner any day of the week. Scared shitless I’m world class. Two years ago, in the ‘border incident’ with Scorron, I ran from a patrol of Teutons, five of them on big old destriers. The men I had charge of stayed put, lacking any orders. I find the important thing in running away is not how fast you run but simply that you run faster than the next man. Unfortunately my lads did a piss-poor job of slowing the Scorrons down and that left poor Jal running for his life with hardly twenty years under his belt and a great long list of things still to do – with the DeVeer sisters near the top and dying on a Scorron lance not even making the first page. In any event, the borderlands aren’t the place to stretch a warhorse’s legs and I kept a gap between us by running through a boulderfield at breakneck speed. Without warning I found myself charging into the back of a pitched battle between a much larger force of Scorron irregulars and the band of Red March skirmishers I’d been scouting on behalf of in the first place. I rocketed into the midst of it all, flailed around with my sword in blind terror trying to escape, and when the dust settled and the blood stopped squirting, I discovered myself the hero of the day, breaking the enemy with a courageous attack that showed complete disregard for my own safety.

So here’s the thing: bravery may be observed when a person tramples one fear whilst in secret flight from a greater terror. And those whose greatest terror is being thought a coward are always brave. I, on the other hand, am a coward. But with a little luck, a dashing smile, and the ability to lie from the hip, I’ve done a surprisingly good job of seeming a hero and of fooling most of the people most of the time.

The DeVeers’s wall was a high and forbidding one but it and I were old friends: I knew its curves and foibles as well as any contour Lisa, Sharal, or Micha might possess. Escape routes have always been an obsession of mine.

Most barriers are there to keep the unwashed out, not the washed in. I vaulted a rain barrel, onto the roof of a gardener’s outbuilding, and jumped for the wall. Teeth snapped at my heels as I hauled myself over. I clung by my fingers and dropped. A shiver of relief ran through me as the hound found its voice and scrabbled against the far side of the wall in frustration. The beast had run silent and almost caught me. The silent ones are apt to kill you. The more sound and fury there is, the less murderous the animal. True of men too. I’m nine parts bluster and one part greed and so far not an ounce of murder.

I landed in the street, less heavily this time, free and clear, and if not smelling of roses then at least of azalea and mixed herbs. Alain would be a problem for another day. He could take his place in the queue. It was a long one and at its head stood Maeres Allus clutching a dozen promissory notes, IOUs, and intents to pay drunkenly scrawled on whores’ silken lingerie. I stood, stretched, and listened to the hound complain behind the wall. I’d need a taller wall than that to keep Maeres’ bullies at bay.

Kings Way stretched before me, strewn with shadows. On Kings Way the townhouses of noble families vie with the ostentation of merchant-princes’ mansions, new money trying to gleam brighter than the old. The city of Vermillion has few streets as fine.

‘Take him to the gate! He’s got the scent.’ Voices back in the garden.

‘Here, Pluto! Here!’

That didn’t sound good. I set off sprinting in the direction of the palace, sending rats fleeing and scattering dungmen on their rounds, the dawn chasing after me, throwing red spears at my back.

2

The palace at Vermillion is a sprawling affair of walled compounds, exquisite gardens, satellite mansions for extended family, and finally the Inner Palace, the great stone confection that has for generations housed the kings of Red March. The whole thing is garnished with marble statuary teased into startlingly lifelike forms by the artistry of Milano masons, and a dedicated man could probably scrape enough gold leaf off the walls to make himself slightly richer than Croesus. My grandmother hates it with a passion. She’d be happier behind granite barricades a hundred feet thick and spiked with the heads of her enemies.

Even the most decadent of palaces can’t be entered without some protocol, though. I slipped in via the Surgeons’ Gate, flipping a silver crown to the guard.

‘Got you out early again, Melchar.’ I make a point of knowing the guards’ names. They still think of me as the hero of Aral Pass and it’s helpful to have the gatekeepers on side when your life dangles from as large a web of lies as mine does.

‘Aye, Prince Jal. Them’s as works best works hardest they do say.’

‘So true.’ I had no idea what he’d said but my fake laugh is even better than my real one, and nine-tenths of being popular is the ability to jolly the menials along. ‘I’d get one of those lazy bastards to take a turn.’ I nodded toward the lantern glow bleeding past the crack of the guardhouse door, and strolled on through the gates as Melchar drew them open.

Once inside, I made a straight line for the Roma Hall. As the queen’s third son, Father got invested in the Roma Hall, a palatial Vatican edifice constructed by the pope’s own craftsmen for Cardinal Paracheck way back whenever. Grandmother has little enough time for Jesu and his cross though she’ll say the words at celebrations and look to mean them. She has far less time for Roma, and none at all for the pope that sits there now – the Holy Cow, she calls her.

As Father’s third son I get bugger all. A chamber in Roma Hall, an unwanted commission in the Army of the North, one that didn’t even swing me a cavalry rank since the northern borders are too damn hilly for horse. Scorron deploy cavalry on the borders but Grandmother declared their pigheadedness a failing the Red March should exploit rather than a foolishness we should continue to follow. Women and war don’t mix. I’ve said it before. I should have been breaking hearts on a white charger, armoured for tourney. But no, that old witch had me crawling around the peaks trying not to get murdered by Scorron peasants.

I entered the Hall – really a collection of halls, staterooms, a ballroom, kitchens, stables, and a second floor with endless bedchambers – by the west port, a service door meant for scullions and such. Fat Ned sat at guard, his halberd against the wall.

‘Ned!’

‘Master Jal!’ He woke with a start and came perilously close to tipping the chair over backwards.

‘As you were.’ I gave him a wink and went by. Fat Ned kept a tight lip and my excursions were safe with him. He’d known me since I was a little monster bullying the smaller princes and princesses and toadying to the ones big enough to clout me. He’d been fat back in those days. The flesh hung off him now as the reaper closed in for the final swing, but the name stuck. There’s power in a name. ‘Prince’ has served me very well – something to hide behind when trouble comes, and ‘Jalan’ carries echoes of King Jalan of the Red March, Fist of the Emperor back when we had one. A title and a name like Jalan carry an aura with them, enough to give me the benefit of the doubt – and there was never a doubt I needed that.

I nearly made it back to my room.

‘Jalan Kendeth!’

I stopped two steps from the balcony that led to my chambers, toe poised for the next step, boots in my hand. I said nothing. Sometimes the bishop would just bellow my name when he discovered random mischief. In fairness I was normally the root cause. This time however he was looking directly at me.

‘I see you right there, Jalan Kendeth, footsteps black with sin as you creep back to your lair. Get down here!’

I turned with an apologetic grin. Churchmen like you to be sorry and often it doesn’t matter what you’re sorry about. In this case I was sorry for being caught.

‘And the best of mornings to you, your excellency.’ I put the boots behind my back and swaggered down toward him as if it had been my plan all along.

‘His eminence directs me to present your brothers and yourself at the throne room by second bell.’ Bishop James scowled at me, cheeks grey with stubble as if he too had been turfed out of bed at an unreasonable hour, though perhaps not by Lisa DeVeer’s shapely foot.

‘Father directed that?’ He’d said nothing at table the previous night and the cardinal was not one to rise before noon whatever the good book had to say about sloth. They call it a deadly sin but in my experience lust will get you into more trouble and sloth’s only a sin when you’re being chased.

‘The message came from the queen.’ The bishop’s scowl deepened. He liked to attribute all commands to Father as the church’s highest, albeit least enthusiastic, representative in Red March. Grandmother once said she’d been tempted to set the cardinal’s hat on the nearest donkey but Father had been closer and promised to be more easily led. ‘Martus and Darin have already left.’

I shrugged. ‘They arrived before me too.’ I’d yet to forgive my elder brothers that slight. I stopped, out of arms’ reach as the bishop loved nothing better than to slap the sin out of a wayward prince, and turned to go upstairs. ‘I’ll get dressed.’

‘You’ll go now! It’s almost second bell and your preening never takes less than an hour.’

As much as I would have liked to dispute the old fool he happened to be right and I knew better than to be late for the Red Queen. I suppressed a sneer and hurried past him. I had on what I’d worn for my midnight escapades and whilst it was stylish enough, the slashed velvets hadn’t fared too well during my escape. Still, it would have to serve. Grandmother would rather see her spawn battle armoured and dripping blood in any event, so a touch of mud here and there might earn me some approval.

3

I came late to the throne room with the second bell’s echoes dying before I reached the bronze doors, huge out-of-place things stolen from some still-grander palace by one of my distant and bloody-handed relatives. The guards eyed me as if I might be bird crap that had sailed uninvited through a high window to splat before them.

‘Prince Jalan.’ I rolled my hands to chivvy them along. ‘You may have heard of me? I am invited.’

Without commentary the largest of them, a giant in fire-bronze mail and crimson plumed helm, hauled the left door wide enough to admit me. My campaign to befriend every guard in the palace had never penetrated as far as Grandmother’s picked men: they thought too much of themselves for that. Also they were too well paid to be impressed by my largesse, and perhaps forewarned against me in any case.

I crept in unannounced and hurried across the echoing expanse of marble. I’ve never liked the throne room. Not for the arching grandness of it, or the history set in grim-faced stone and staring at us from every wall, but because the place has no escape routes. Guards, guards, and more guards, along with the scrutiny of that awful old woman who claims to be my grandmother.

I made my way toward my nine siblings and cousins. It seemed this was to be an audience exclusively for the royal grandchildren: the nine junior princes and singular princess of Red March. By rights I should have been tenth in line to the throne after my two uncles, their sons, my father and elder brothers, but the old witch who’d kept that particular seat warm these past forty years had different ideas about succession. Cousin Serah, still a month shy of her eighteenth birthday, and containing not an ounce of whatever it is that makes a princess, was the apple of the Red Queen’s eye. I won’t lie, Serah had more than several ounces of whatever it is that lets a woman steal the sense from a man and accordingly I would gladly have ignored the common views on what cousins should and shouldn’t get up to. Indeed I’d tried to ignore them several times, but Serah had a vicious right hook and a knack for kicking the tenderest of spots that a man owns. She’d come today wearing some kind of riding suit in fawn and suede that looked better suited to the hunt than to court. But, damn, she looked good.

I brushed past her and elbowed my way in between my brothers near the front of the group. I’m a decent sized fellow, tall enough to give men pause, but I don’t normally care to stand by Martus and Darin. They make me look small and, with nothing to set us apart, all with the same dark-gold hair and hazel eyes, I get referred to as ‘the little one’. That I don’t like. On this occasion, though, I was prepared to be overlooked. It wasn’t just being in the throne room that made me nervous. Nor even because of Grandmother’s pointed disapproval. It was the blind-eye woman. She scares the hell out of me.

I first saw her when they brought me before the throne on my fifth birthday, my name day, flanked by Martus and Darin in their church finest, Father in his cardinal’s hat, sober despite the sun having passed its zenith, my mother in silks and pearls, a clutch of churchmen and court ladies forming the periphery. The Red Queen sat forward in her great chair booming out something about her grandfather’s grandfather, Jalan, the Fist of the Emperor, but it passed me by – I’d seen her. An ancient woman, so old it turned my stomach to look at her. She crouched in the shadow of the throne, hunched up so she’d be hidden away if you looked from the other side. She had a face like paper that had been soaked then left to dry, her lips a greyish line, cheekbones sharp. Clad in rags and tatters, she had no place in that throne room, at odds with the finery, the fire-bronzed guards and the glittering retinue come to see my name set in place upon me. There was no motion in the crone: she could almost have been a trick of the light, a discarded cloak, an illusion of lines and shade.

‘… Jalan?’ The Red Queen stopped her litany with a question.

I had answered with silence, tearing my gaze from the creature at her side.

‘Well?’ Grandmother narrowed her regard to a sharp point that held me.

Still I had nothing. Martus had elbowed me hard enough to make my ribs creak. It hadn’t helped. I wanted to look back at the old woman. Was she still there? Had she moved the moment my eyes left her? I imagined how she’d move. Quick like a spider. My stomach made a tight knot of itself.

‘Do you accept the charge I have laid upon you, child?’ Grandmother asked, attempting kindness.

My glance flickered back to the hag. Still there, exactly the same, her face half-turned from me, fixed on Grandmother. I hadn’t noticed her eye at first, but now it drew me. One of the cats at the Hall had an eye like that. Milky. Pearly almost. Blind, my nurse called it. But to me it seemed to see more than the other eye.

‘What’s wrong with the boy? Is he simple?’ Grandmother’s displeasure had rippled through the court, silencing their murmurs.

I couldn’t look away. I stood there sweating. Barely able to keep from wetting myself. Too scared to speak, too scared even to lie. Too scared to do anything but sweat and keep my eyes on that old woman.

When she moved, I nearly screamed and ran. Instead just a squeak escaped me. ‘Don-don’t you see her?’

She stole into motion. So slow at first you had to measure her against the background to be sure it wasn’t imagination. Then speeding up, smooth and sure. She turned that awful face toward me, one eye dark, the other milk and pearl. It had felt hot, suddenly, as if all the great hearths had roared into life with one scorching voice, sparked into fury on a fine summer’s day, the flames leaping from iron grates as if they wanted nothing more than to be amongst us.

She was tall. I saw that now, hunched but tall. And thin, like a bone.

‘Don’t you see her?’ My words rising to a shriek, I pointed and she stepped toward me, a white hand reaching.

‘Who?’ Darin beside me, nine years under his belt and too old for such foolishness.

I had no voice to answer him. The blind-eye woman had laid her hand of paper and bones over mine. She smiled at me, an ugly twisting of her face, like worms writhing over each other. She smiled, and I fell.

I fell into a hot, blind place. They tell me I had a fit, convulsions. A ‘lepsy’, the chirurgeon said to Father the next day, a chronic condition, but I’ve never had it again, not in nearly twenty years. All I know is that I fell, and I don’t think I’ve stopped falling since.

Grandmother had lost patience and set my name upon me as I jerked and twitched on the floor. ‘Bring him back when his voice breaks,’ she said.

And that was it for eight years. I came back to the throne room aged thirteen, to be presented to Grandmother before the Saturnalia feast in the hard winter of 89. On that occasion, and all others since, I’ve followed everyone else’s example and pretended not to see the blind-eye woman. Perhaps they really don’t see her because Martus and Darin are too dumb to act and poor liars at that, and yet their eyes never so much as flicker when they look her way. Maybe I’m the only one to see her when she taps her fingers on the Red Queen’s shoulder. It’s hard not to look when you know you shouldn’t. Like a woman’s cleavage, breasts squeezed together and lifted for inspection, and yet a prince is supposed not to notice, not to drop his gaze. I try harder with the blind-eye woman and for the most part I manage it – though Grandmother’s given me an odd look from time to time.