Полная версия:

Emperor of Thorns

EMPEROR

OF THORNS

Book Three of The Broken Empire

Mark Lawrence

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Mark Lawrence 2013

Jacket Layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2013

Jacket Illustration © Jason Chan.

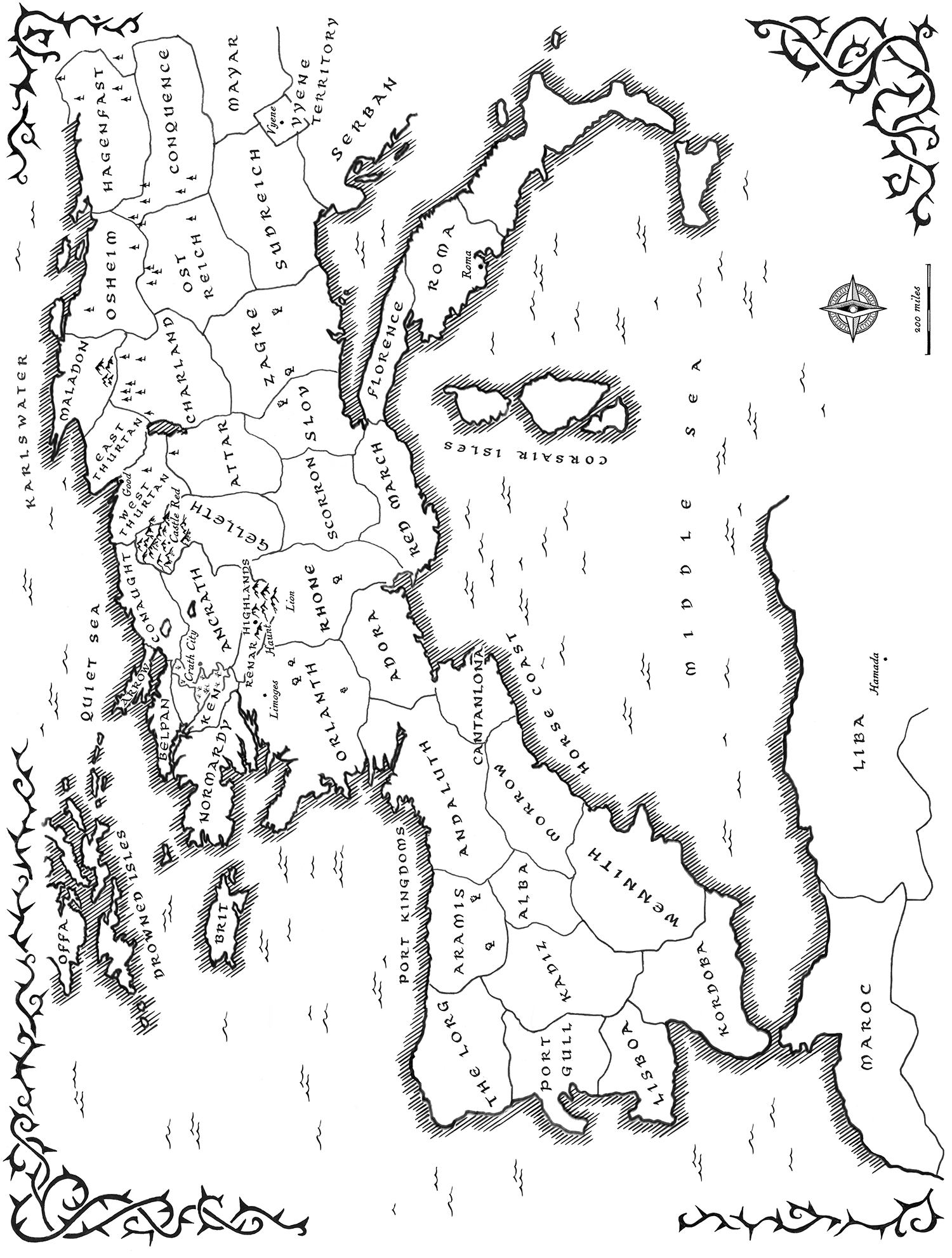

Map © Andrew Ashton

Mark Lawrence asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007439072

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2013 ISBN: 9780007439072

Version: 2018-05-02

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

The Story So Far

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

An Afterthought

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Mark Lawrence

About the Publisher

Dedicated to my son, Bryn.

The Story So Far

For those of you who have had to wait a year for this book I provide a brief synopsis of books 1 and 2, so that your memories may be refreshed. Here I carry forward only what is of importance to the tale that follows.

1 Jorg’s mother and brother, William, were killed when he was nine: he hung hidden in the thorns and witnessed it. His uncle sent the assassins.

2 Jorg’s father, Olidan, is not a nice man. He killed Jorg’s dog when Jorg was six, and stabbed Jorg in the chest when he was fourteen.

3 Jorg’s father still rules in Ancrath, married now to Sareth. Sareth’s sister Katherine is Jorg’s step-aunt and something of an obsession for him.

4 Jorg accidentally (though not guiltlessly) killed his baby step-brother Degran.

5 A man named Luntar put Jorg’s memory of the incident in a box. Jorg has now recovered the memory.

6 A number of magically-gifted individuals work behind the many thrones of the Broken Empire, competing with each other and manipulating events to further their own control.

7 We left Jorg still on his uncle’s throne in Renar. The princes of Arrow lay dead, their army shattered and the six nations gathered under Orrin of Arrow’s rule ripe for the picking.

8 We left Jorg the day after his wedding to twelve-year-old Queen Miana.

9 Jorg had sent men to recover his badly-wounded chancellor, Coddin, from the mountainside.

10 Katherine’s diary was found in the destruction outside the Haunt – whether she survived where her baggage train did not is unknown.

11 Red Kent was badly burned in the fight.

12 Jorg discovered there are ghosts of the Builders in the network of machines they left behind.

13 Jorg learned from one such ghost, Fexler Brews, that what he calls magic exists because the Builder scientists changed the way the world works. They made it possible for a person’s will to affect matter and energy directly.

14 The gun Jorg used to conclude the siege on the Haunt was taken from Fexler Brews’ suicide.

15 The powers over necromancy and fire were burned out of Jorg when they nearly destroyed him at the finale of the battle for the Haunt.

16 The Dead King is a powerful individual who watches the living from the deadlands and has shown a particular interest in Jorg.

17 Chella, a necromancer, has become an agent of the Dead King.

18 Every four years the rulers of the hundred fragments of empire convene in the capital Vyene for Congression – a truce period during which they vote for a new emperor. In the hundred years since the death of the last steward no candidate has managed to secure the necessary majority.

19 In the earlier thread ‘Four Years Earlier’ we left Jorg at his grandfather’s castle on the Horse Coast. The mathmagician, Qalasadi, had escaped after failing to poison the nobles. The Builder-ghost, Fexler, had given Jorg the view-ring that offers interactive views of the world from satellites and other optical resources.

Prologue

Kai stood before the old-stone, a single rough block set upright in the days when men knew nothing but wood and rock and hunting. Or perhaps they knew more than that, for they had set the old-stone in a place of seeing. A point where veils thinned and lifted and secrets might be learned or told. A place where the heavens stood a little lower, such that the sky-sworn might touch them more easily.

The local men called the promontory ‘the Finger’, which Kai supposed was apt if dull. And if it were a finger then the old-stone stood on the knuckle. Here the finger lay sixty yards across and at the edges fell a similar distance to meet the marsh in a series of steep and rocky steps.

Kai took a deep breath and let the cold air fill his lungs, let the dampness infect him, slowed his heart, and listened for the high, sad voice of the old-stone, less of a sound than a memory of sound. His vision lifted from him with just a whisper of pain. The point of Kai’s perception vaulted skyward, leaving his flesh beside the monolith. He watched now from a bright valley between two tumbling banks of cloud, watched himself as a dot upon the Finger, and the promontory itself a mere sliver of land reaching out into the vastness of the Reed Sea. At this distance the River Rill became a ribbon of silver running to the Lake of Glass.

Kai flew higher. The ground fell away, growing more abstract with each beat of his mind-born wings. The mists swirled, and the clouds held him again in their cool embrace.

Is this what death is like? A cold whiteness, for ever and ever amen?

Kai resisted the cloud’s pull and found the sun again. The sky-sworn could so easily lose themselves in the vastness of the heavens. Many did, leaving flesh to die and haunting the empty spaces above. A core of selfishness bound Kai to his existence. He knew himself well enough to admit that. An old strand of greed, an inability to let go. Failings of a kind perhaps, but here an asset that would keep him whole.

He flew above the soft brilliance of the clouds, weaving his path amongst their turrets and towers. A seris broke the pillowed alabaster, ghost-faint even to the eye of Kai’s mind, its sinuous form plunging in and out of sight, a hundred feet long and thicker than a man. Kai called to it. The cloud-snake coiled on itself; describing lazy circles as it drew ever closer.

‘Old friend.’ Kai hailed it. As many as a hundred seris swarmed amid the thunderheads when the land-breaker storms came, but each seris knew what every seris knew, so to Kai’s mind there was only one. Perhaps the seris were remnants of sky-sworn who had forgotten themselves, forgotten all that they were to dance among the clouds. Or maybe they had always been, requiring no birth and knowing no death.

The seris fixed Kai with the cold blue glow of its eye-pits. He felt the chill of its mind-touch, slow and curious. ‘Still the woman?’

‘Always the woman.’ Kai watched the light on the clouds. Architectural clouds, just ready for God’s hand to shape, ready to be cathedrals, towers, monsters … It amused him that the seris thought he always brought the same girl to the Finger.

Maybe seris think there’s just one man, one woman, and lots of bodies.

The seris moved around Kai in a corkscrew, as if he were there in person, cocooning him in its coils. ‘You would have one shadow?’

Kai smiled. The seris thought of human love as clouds coming together, sometimes brushing one to another, sometimes building to a storm, sometimes lost one in the other – casting one shadow.

‘Yes, to have one shadow.’ Kai surprised himself with the heat in his voice. He wanted what the seris had. Not just a roll in the heather. Not this time.

‘Make it.’ The voice of the seris spoke beneath his skin, though he had left that far below.

‘Make it happen? It isn’t that easy.’

‘You do not want?’ The seris rippled. Kai knew it for laughter.

‘Oh, I want.’ She just has to walk in the room and I’m on fire. The scent of her! I close my eyes and I’m in the Gardens of Bethda.

‘A storm comes.’ Sorrow tinged the seris’s voice.

Kai puzzled. He’d seen no sign of a storm brewing.

‘They rise,’ the seris said.

‘The dead?’ Kai asked, the old fear creeping over him.

‘Worse.’ One word, too much meaning.

‘Lichkin?’ Kai stared, he could see nothing. Lichkin only come in the dark.

‘They rise,’ the seris said.

‘How many?’ Don’t let it be all seven! Please.

‘Many. Like the rain.’ The seris left. The mist from which it wove its body drifted formless. Kai had never seen a seris fall apart like that. ‘Make one shadow.’ The voice hung in the air.

Kai’s vision arrowed toward the ground. He dived for the Finger. Sula stood at the fingertip, on the very edge, a white dot, growing swiftly. Sight slammed into body, hard enough to make him fall to his knees. He scrambled up, disoriented for a moment, then tore off toward Sula. He reached her in less than a minute, and bent double before her, heaving in his breath.

‘You were a long time.’ Sula turned at his approach. ‘I thought you’d forgotten about me, Kai Summerson.’

‘Forgive me, my lady?’ he gasped, and grinned, her beauty pushing away his panic. It seemed silly now. From on high he’d seen nothing to worry him.

Sula’s pout became smile, the sun reached down to light her face, and for a moment Kai forgot about the seris’s warning. Lichkin travel at night. He took her hands and she came to him. She smelled of flowers. The softness of her breasts against his chest made his heart skip. For a moment he could see only her eyes and lips. The fingers of one hand locked with hers, the other ran along her throat, feeling the pulsing heat of her.

‘You shouldn’t stand so close to the edge,’ he said, though she stole his breath. Just a yard behind her the tip of the Finger crumbled away into two hundred feet of cliffs, stepping sharply down into the surrounding marsh.

‘You sound like Daddy.’ Sula cocked her head and leaned into him. ‘You know, he even told me not to go with you today? That Kai Summerson is low-born trash, he said. He wanted me to stay cooped up in Morltown while he did his business deals.’

‘What?’ Kai let go of Sula’s hands. ‘You said he agreed.’

Sula giggled and put on a gruff voice. ‘I’ll not have my daughter gallivanting with a Guardian captain!’ She laughed and returned to her normal tones. ‘Did you know, he thinks you have a “reputation”?’

Kai did have a reputation, and a man like Merik Wineland could make things very difficult for him.

‘Look, Sula, we’d better go. There may be trouble coming.’

The tight little lines of a frown marred Sula’s perfect brow. ‘Trouble coming?’

‘I had an ulterior motive for bringing you here,’ Kai said.

Sula grinned where other girls might blush.

‘Not that,’ Kai said. ‘Well, that too, but I was scheduled to check the area. Observe the marsh.’

‘I’ve been watching from the cliff while you were gone. There’s nothing down there!’ Sula turned from him and gestured to the green infinity of the mire. Then she saw it. ‘What’s that?’

Across the Reed Sea a mist was rising. It ran in white streams, spreading from the east, blood-tinged by the setting sun.

‘They’re coming.’ Kai struggled to speak. He found his voice and tried a confident smile. It felt like a grimace. ‘Sula, we have to move fast. I need to report to Fort Aral. I’ll get you over the Mextens and leave you at Redrocks. You’ll be safe there. A wagon will get you to Morltown.’

The darts flew with a noise like somebody blowing out candles, a series of short sudden breaths. Three clustered just below Sula’s right armpit. Three thin black darts, stark against the whiteness of her dress. Kai felt the sting in his neck, like the bite of horseflies.

The mire ghouls swarmed over the tip of the Finger, grey and spider-like, swift and silent. Kai ripped his short sword from its scabbard. It felt heavier than lead. The numbness was in his fingers already and the sword fell from his clumsy grasp.

A storm’s coming.

1

I failed my brother. I hung in the thorns and let him die and the world has been wrong since that night. I failed him, and though I’ve let many brothers die since, that first pain has not diminished. The best part of me still hangs there, on those thorns. Life can tear away what’s vital to a man, hook it from him, one scrap at a time, leaving him empty-handed and beggared by the years. Every man has his thorns, not of him, but in him, deep as bones. The scars of the briar mark me, a calligraphy of violence, a message blood-writ, requiring a lifetime to translate.

The Gilden Guard always arrive on my birthday. They came for me when I turned sixteen, they came to my father and to my uncle the day I reached twelve. I rode with the brothers at that time and we saw the guard troop headed for Ancrath along the Great West Road. When I turned eight I saw them first hand, clattering through the gates of the Tall Castle on their white stallions. Will and I had watched in awe.

Today I watched them with Miana at my side. Queen Miana. They came clattering through a different set of gates into a different castle, but the effect was much the same, a golden tide. I wondered if the Haunt would hold them all.

‘Captain Harran!’ I called down. ‘Good of you to come. Will you have an ale?’ I waved toward the trestle tables set out before him. I’d had our thrones brought onto the balcony so we could watch the arrival.

Harran swung himself from the saddle, dazzling in his fire-gilt steel. Behind him guardsmen continued to pour into the courtyard. Hundreds of them. Seven troops of fifty to be exact. One troop for each of my lands. When they had come four years before, I warranted just a single troop, but Harran had been leading it then as now.

‘My thanks, King Jorg,’ he called up. ‘But we must ride before noon. The roads to Vyene are worse than expected. We will be hard pushed to reach the Gate by Congression.’

‘Surely you won’t rush a king from his birthday celebrations just for Congression?’ I sipped my ale and held the goblet aloft. ‘I claim my twentieth year today, you know.’

Harran made an apologetic shrug and turned to review his troops. More than two hundred were already crowded in. I would be impressed if he managed to file the whole contingent of three hundred and fifty into the Haunt. Even after extension during the reconstruction, the front courtyard wasn’t what one would call capacious.

I leaned toward Miana and placed a hand on her fat belly. ‘He’s worried if I don’t go there might be another hung vote.’

She smiled at that. The last vote that was even close to a decision had been at the second Congression – the thirty-third wasn’t likely to be any nearer to setting an emperor on the throne than the previous thirty.

Makin came through the gates at the rear of the guard column with a dozen or so of my knights, having escorted Harran through the Highlands. A purely symbolic escort since none in their right mind, and few even in their wrong mind, would get in the way of a Gilden Guard troop, let alone seven massed together.

‘So Miana, you can see why I have to leave you, even if my son is about to fight his way out into the world.’ I felt him kick under my hand. Miana shifted in her throne. ‘I can’t really say no to seven troops.’

‘One of those troops is for Lord Kennick, you know,’ she said.

‘Who?’ I asked it only to tease her.

‘Sometimes I think you regret turning Makin into my lord of Kennick.’ She gave me that quick scowl of hers.

‘I think he regrets it too. He can’t have spent more than a month there in the last two years. He’s had the good furniture from the Baron’s Hall moved to his rooms here.’

We fell silent, watching the guard marshal their numbers within the tight confines of the courtyard. Their discipline put all other troops to shame. Even Grandfather’s Horse Coast cavalry looked a rabble next to the Gilden Guard. I had once marvelled at the quality of Orrin of Arrow’s travel guard, but these men stood a class apart. Not one of the hundreds didn’t gleam in the sun, the gilt on their armour showing no sign of dirt or wear. The last emperor had deep pockets and his personal guard continued to dip into them close on two centuries after his death.

‘I should go down.’ I made to get up, but didn’t. I liked the comfort. Three weeks’ hard riding held little appeal.

‘You should.’ Miana chewed on a pepper. Her tastes had veered from one extreme to another in past months. Of late she’d returned to the scalding flavours of her homeland on the Horse Coast. It made her kisses quite an adventure. ‘I should give you your present first though.’

I raised a brow at that and tapped her belly. ‘He’s cooked and ready?’

Miana flicked my hand away and waved to a servant in the shadows of the hall. At times she still looked like the child who’d arrived to find the Haunt all but encircled, all but doomed. At a month shy of fifteen the most petite of serving girls still dwarfed her, but at least pregnancy had added some curves, filled her chest out, put some colour in her cheeks.

Hamlar came out with something under a silk cloth, long and thin, but not long enough for a sword. He offered it to me with a slight bow. He’d served my uncle for twenty years but had never shown me a sour glance since I put an end to his old employment. I twitched the cloth away.

‘A stick? My dear, you shouldn’t have.’ I pursed my lips at it. A nice enough stick it had to be said. I didn’t recognize the wood.

Hamlar set the stick on the table between the thrones and departed.

‘It’s a rod,’ Miana said. ‘Lignum Vitae, hard, and heavy enough to sink in water.’

‘A stick that could drown me …’

She waved again and Hamlar returned with a large tome from my library held before him, opened to a page marked with an ivory spacer.

‘It says there that the Lord of Orlanth won the hereditary right to bear his rod of office at the Congressional.’ She set a finger to the appropriate passage.

I picked the rod up with renewed interest. It felt like an iron bar in my hand. As King of the Highlands, Arrow, Belpan, Conaught, Normardy, and Orlanth, not to mention overlord of Kennick, it seemed that I now held royal charter to carry a wooden stick where all others must walk unarmed. And thanks to my pixie-faced, rosy-cheeked little queen, my stick would be an iron-wood rod that could brain a man in a pot-helm.

‘Thank you,’ I said. I’ve never been one for affection or sentiment, but I liked to think we understood each other well enough for her to know when something pleased me.

I gave the rod an experimental swish and found myself sufficient inspiration to leave my throne. ‘I’ll look in on Coddin on the way down.’

Coddin’s nurses had anticipated me. The door to his chambers stood open, the window shutters wide, musk sticks lit. Even so the stench of his wound hung in the air. Soon it would be two years since the arrow struck him and still the wound festered and gaped beneath the physician’s dressings.

‘Jorg.’ He waved to me from his bed, made up by the window and raised so he too could see the guard arrive.

‘Coddin.’ The old sense of unfocused guilt folded around me.

‘Did you say goodbye to her?’

‘Miana? Of course. Well …’

‘She’s going to have your child, Jorg. Alone. Whilst you’re off riding.’

‘She’ll hardly be alone. She has no end of maids and ladies-in-waiting. Damned if I know their names or recognize half of them. Seems to be a new one every day.’

‘You played your part in this, Jorg. She will know you’re absent when the time comes and it will be harder on her. You should at least make a proper goodbye.’

Only Coddin could lecture me so.

‘I said … thank you.’ I twirled my new stick into view. ‘A present.’

‘When you’re done here go back up. Say the right things.’

I gave the nod that means perhaps. It seemed to be enough for him.

‘I never tire of watching those boys at horse,’ he said, glancing once more at the gleaming ranks below.

‘Practice makes perfect. They’d do better to practise war though. Being able to back a horse into a tight corner makes a pretty show but—’