Полная версия:

The Draughtsman

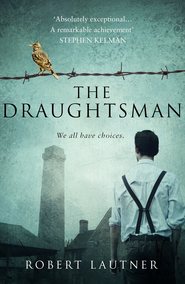

THE DRAUGHTSMAN

Robert Lautner

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on

historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Robert Lautner asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover images © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images (figure); www.Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Every effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders. If there are any inadvertent omissions we apologise to those concerned and will undertake to include suitable acknowledgements in all future editions.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008126711

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008126735

Version: 2018-01-09

‘It is not so much the kind of person a man is as the kind of situation in which he finds himself that determines how he will act.’

Stanley Milgram, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View (1974)

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part Two

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Part Three

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Part Four

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Robert Lautner

About the Publisher

Prologue

Erfurt, Germany,

February 2011

The site had become a squat for the disenfranchised, for anarchic youth. They even formed a cultural group. Artists and rebels. Appropriate. Perhaps.

Over the bridge, across the railway that once moved the iron goods from the factory to the camp at Buchenwald, Erfurt still maintained its tourist heart, its picture-book heart. A place where romance comes. Where carriages drawn by white horses still mingle with trams and buses and young and old marrieds hold hands crossing the market square. Rightly fitting, just so, that the industrial quarter on Sorbenweg ignored, left to rot, to be forgotten. A despised relative a hurt family no longer calls upon. Its only colour in the graffiti, signs and spray-paint portraits that only the youth understood.

The squatters removed, the land and remaining dying buildings reimagined. Erfurt ready to remember that history, no matter its shade, had something to pass on.

Myra Konns ran the morning tours of the museum risen from the ruins of the Topf administration buildings. She guided school-children through the original ISIS drafting tables they had found scattered and vandalised over the years by the transients, guided them through the director’s rooms still furnished with the wide cabinets that once held drafts for cremation ovens. Labels still sitting in their brass handles. The impression of ink soft and leaving. The drawers empty. Yawning only dust and memory. All restored now.

Myra would show them the small canisters with the clay plaques that the factory made to store ashes to be collected by relatives; a legal requirement until someone decided that it was no longer required. Hundreds of them found abandoned and empty in an attic in Buchenwald. These and other smaller items all on the third floor, where the drafting tables were repaired and displayed, where the chief designer’s office had been recreated, where the tours could still see from the window to Ettersberg mountain as the draughtsmen at their tables would have done and Myra would point out that the smoke from the Buchenwald ovens could be seen crawling over the mountain all day. All day.

The oven doors, removed from Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the most sombre items of the tour. No need to highlight the prominence of the company plaque set above them. Topf and Sons exhibited now as the ‘Engineers of the Final Solution’. A brochure saying so.

In one display cabinet Myra would put her hand to a drawing of an experimental oven, never employed; for the allies had closed in before its realisation. Beside it a letter from a director to Berlin explaining the function of the new design. And Myra would always choose her words with care.

‘It works on four levels over two floors, one of which is the basement, where the morgue would traditionally be, replaced by the furnace. The deceased would be put in at the top and a series of rollers over grates would convey them to the furnace. The letter confirms the effectiveness of the design at being able to work continuously. Day and night. Reducing the need for coal as the oven was intended to be fuelled by the deceased themselves. Hundreds, possibly thousands of corpses a day. No intention to distinguish one from the other. A machine. An eradication device criminal in nature and design. Thankfully never introduced. The Allies having liberated Auschwitz some months before.’

A hand went up in the midst of the group. Myra took a breath. An old man. Always a sparse group of old men and women dawdling amongst the children. In her induction, just the month before when the museum opened, Myra had been informed to be especially aware of the aged visitors. The air about the place theirs. The tomb of it theirs.

‘Yes, sir?’

‘Excuse me, Fräulein,’ he bowed slightly. White, pomade-brushed hair and grey-blue eyes that smarted from the cold February wind outside, made worse by the radiator warmth of the halls. He wiped his eyes behind his glasses.

‘That correspondence does not refer to the design of the continuous oven. Of that oven.’

Myra’s breath released. Always one.

‘Sir. This letter has been donated from the Russian archives. It has been verified by many experts.’

He moved forward, his age more apparent in his careful step, in his politeness in moving through the young elbows that might bruise him as he passed.

‘Forgive, Fräulein. That oven – the continuous oven – was patented in 1942. That letter was for a circular design. From Herr Prüfer. From one of the engineers.’ He tapped a finger on the glass. ‘This drawing was for a new annotation of the previous patent. Ordered to be redrafted in May 1944.’

Myra looked between him and the glass display. Always one.

‘I’m sure it is not a mistake, sir.’

He wiped his forehead.

‘We have all made mistakes, Fräulein.’

He bent to the cabinet, lifted his glasses to peer at the fading paper within.

‘This is only an error. This article comes from the Americans, does it not?’

‘It is paired with the letter from the Russian archive.’

‘No.’ His lips thinned. ‘I can assure you.’

‘How is that, sir?’ As respectful as she could.

He moved towards her, as if he did not want the children to hear, as if he wished no-one but Myra to collect his whisper. She could smell the pomade in his hair, looked down at the expensive shoes as she moved to not tread on them.

‘Because I gave it to the Americans.’ His hand back to the glass shielding the exhibit. ‘Because I drew it.’

*

Myra found him sat outside. Cap playing in his hands, eyes at the ground. Sat beside him without invite. He began as if the conversation had started minutes before and he finishing it off, rounding it off politely so he could put on his cap and leave.

‘We were married in Switzerland. In ’41. Her parents had moved there. Run there. Etta’s father – Etta was my wife – was wealthy. Wealthy for those days. A property man. I thought I had done well to marry a woman of means. Poor all my life. Where are you from, Fräulein?’

‘Munich.’

‘Ah. Just so. I was born in Erfurt. You know the Merchants’ Bridge? That was my childhood home. An ancient place. The people ancient. Me – a boy – an intruder on the bridge. When my father needed to tan me I would hide all about the stairs and gutters. The little paths. Right under the bridge. He would never find me. Old cities full of hiding places. They are built around the hiding places. Modern cities are not like this. They are built straight and plain. Wide. Open. It is because the people do not need to hide as much. Old cities. They cringe around the churches like children to their mother’s skirts.’

Myra watched him look about the walls. Breathing them.

‘I was grateful to work here. No-one will understand. My Etta did not even understand. And she knew everything.’ The wink of German humour.

Myra leaned closer, had to speak over the noise of a new arrival of children.

‘What happened here?’

He put back his cap. Not to leave. Against the cold.

‘Nothing. Nothing happened here.’ Sat back against the bench. ‘Always the problem.’

He rubbed the salt and pepper grey of his stubble. Grunted at the disapproval of it.

‘Left early,’ he said. ‘To get here. I need a shave.’

Chapter 1

Erfurt, Germany,

April 1944

I shave every other day. The new blade already dull when purchased, yet twice as expensive as the year before. Steel for higher order than grooming. But I will shave tomorrow morning as I am not the man I was yesterday. I have work now. My first since I graduated and married.

There is the man you were the last year, without work, and then there is this day. And nothing is the same. The clock ticks down the hours to your first day, not just to the next day. A man has signed your name alongside his own. A contract. Real work.

And you begin.

I always stand by the curtained window looking over the street three floors below when Etta and I have these serious talks. I have a cigarette and she lays on the chaise-longue that her mother gave her for our wedding. The window half-open to exhale my evening smoke and to watch the street pass by and listen to the trains bringing workers home. Our voices never raise. We have become dulled. Like the blades of my razor that were never sharp. I am too weary from not working and she is tired from me not doing the same. Only couples understand such malaise.

‘It is a job, Etta. Forty marks a week. We owe two months’ rent.’

‘A skilled draughtsman. Forty marks a week.’ Tutted her disdain.

I draw on my cigarette, blow it against the curtain, just to annoy.

‘It is a start. A beginning.’

‘A low one. You start from the bottom. Four years of study and you gain the lowest rung.’

‘I have no experience. Herr Prüfer has selected me because he came from the same study. That is a good wage for a new man. You want to stay in these rooms forever?’

A one-bed apartment with a kitchenette off the living-room. Etta put up new curtains which made all the difference. The curtains I was blowing smoke on.

She is draped over the chaise-longue like Garbo, her breasts accentuated through her dark dress, the one with the small red roses the same colour as her hair, the evening sun painting them further. I go back to smoking through the curtains and the window. A man below removes his homburg to wipe his sweating pate. Even at six o’clock it is still warm, warm for April, but all the businessmen are still in full dress, except that waistcoats seem to have vanished. Either a lack of textiles or some American trend. The harder grimier worker in cap, cardigan and jacket. That will not be me. I will be with the businessmen. I can feel Etta seething behind me.

‘I did not expect to be the wife of a man who makes pictures of grain silos for a living.’

Pictures. Pictures she says. Belittled with a word. Austrian women do this well, even the ones born in Erfurt like Etta. Austrian by proxy.

‘It is a start.’ I draw a long, calming drag. ‘They do other things. Crematoria. They do dignified crematoria.’

‘How is that “dignified”?’

She said this in that cursing inflection that Austrian women perfect along with their curtsies. Swearing and not swearing. Her mother’s voice.

‘I spoke to Paul about it last week. Before my interview.’

Paul Reul, an old school friend of mine. He had made a name for himself as a crematorist in Weimar, a successful businessman. A thing to be admired in wartime. We did not see him so much since the jazz club where we used to meet had been closed, since we had married. Always the way. Your single friends become strangers.

‘He told me Topf invented the electric and petrol crematoria. Changed the design so you could have a dignified service, like a church, with the oven in the same building. Topf did that. Made a funeral out of it.’

‘It is all disgusting.’

‘Before that the dead were all burnt out the back, a different place. Like hospitals. Just incinerators. Like for refuse.’ I punctuate smoke into the room. Etta revolted. Not at my smoke.

‘Stop talking about it. It is horrible. Why would you talk on such things?’

The cigarette goes out the window. Her disappointment a mystery. Real work. My first contract to draft plans since leaving the university. Silos or not. A start in wartime. Not an end. Not like so many others. But Topf and Sons were hiring. Everywhere else in Erfurt closing. I guess the army had need for a lot of silos.

She swings her legs from the lounger.

‘I have to get ready for work. There is some ham and pickles you can eat.’

She goes to the bedroom removing the pins from her hair as she sways, her voice over her shoulder.

‘I am pleased you have work, Ernst. I am just in a mood. And I shall probably miss you during the day.’

Etta’s café job started at seven. Three nights a week if we were fortunate. Kept us fed when my subsistence ran out and she could always bring home leftovers, sometimes unfinished wine if the diners could afford it. It was long work when it came. Often she would not return until past one, the café closing at ten for the blackout, but the work goes on beyond the leave of guests. Only staff know this. The hard work is after the bill has been paid.

She closed the door to change. Her mystery always maintained by how many doors she could close. Fewer now than in our old place that we could no longer afford. Here I would put my fingers in my ears when she made her toilet, her insistence, the rooms that small. In our bedroom we can hear our neighbours flushing their broken cistern. You don’t find that out when they show you the place.

She puts her make-up on before I wake. We sleep in separate beds, pushed together when desire desires. Three years married and I had never been permitted to know that she washed her undergarments, or seen them drying. As far as I knew she hung those silks out for faeries to attend to.

This her upbringing of course. Better than mine. My confidence in my good looks gave me no doubts why Etta Eischner should fall for a boy from the bridge. My grey-blue eyes and blond hair enough. But not to her parents. No reason for Herr Eischner to see why his daughter loved a penniless student, despite the blue eyes, despite the groomed blond hair. A boy from the bridge. Herr Eischner had plenty of suitable young men she could meet, rich stock like his, good stock. A boy from the bridge. Nothing in his pockets but dreams. Dancing in the clubs. Too much drinking, too much walking late at night. Too many dark alleyways for him to pull her into. The red look on her face when she came home far too late. She refused to join the bridge club or the Rotary, before they were outlawed of course, where good young men with connections and families could be found. The flame hair of her not the least of her fire.

Eventually he settled. Remembered even when little his daughter had always been looking for something she could never find, that even he could not satisfy, not when she was little and not when she had grown and argued with him on his politics and business. And that was why the blue-eyed boy came. She cooled after she had him. Poor boys from the bridge more capable than he where daughters are concerned. ‘Curiosity killed the cat,’ they say. To dismiss and persuade the young to seek. To tut, and warn them to not question. But they forget the final line: ‘But satisfaction brought it back.’ The poor boy from the bridge brought it back. The best the father would get.

I sniff my black tie that needs washing. All ties thin now. Again, either fashion or a textile shortage. I preferred them this way. Less like a noose. Tomorrow it will be a working tie. Odd to be starting new work on a Thursday. You assume Monday. They must be busy. Good. Though I will miss that serial play they put on the radio at lunch time. I suppose only housewives should listen anyway.

Working men do not need the radio.

Chapter 2

Our apartment is on Station Street, a grey shrivelled building next to the largest hotel in Erfurt and we share a double-front door with the radio shop below us. I wink to Frau Klein, our landlady, sweeping the porch. She has not seen me outside the door before nine until now and she eyes me like the Devil.

‘Work to go to, Frau Klein,’ I tell her. ‘I start a new job this morning. Work at last! Won’t you be happy for me?’

She grunts, as those of her profession do when they have been widowed and forced to let out their rooms to young married smiles.

‘I will be happy to be paid.’ And the broom beneath the bosom drags on. But still I whistle as I step by. To add to her disdain of me, of all youth.

My name called from above. Etta with a kiss, a wave.

How fine it still is to have someone you love call out your name, past the time when it was necessary to do so across a fair or a crowded square in courtship, for now you do not need to meet, are always a hand’s reach from each other, and the echoed call of your name is rare. But going to work on your first day a time to hear the call again. And envious men look up with me to the pale shoulder slipped from the gown and the red tussled hair. And then their heads go back to their feet as I stride. Taller than them. If only in pride. I look at their passing fedoras. Eyeing those I may one day pick and choose to purchase. My own poor replica winter-beaten.

I had sold my bicycle, for who needs a bicycle in winter when there is only flakes of tea in the cupboards, so now I would walk to my employment in April sun following all the other black coats and hats to the station. But I am still grinning because I am not like them. I am one better than them. I will not be cramped and stifled in a smoky carriage. I am not an hour or two from my office. I will go through the station and over the footbridge to my work with Etta’s warm body still glowing on me. A mile walk. Just enough time to clear your head and good enough exercise for all the working week to keep off the fat which I will soon be putting on our Sunday table.

I thread through the crowds shuffling to buy their tickets, shuffling to their transits and trucks, and take the iron-capped stairs two at a time. Puffed when I reach the top. In two weeks that will change. In two weeks I might have worn-out shoes but by then be able to buy a pair without care. Or perhaps not. It has been a long time since I looked at the price of shoes.

Over the bridge the landscape changed, you could not even see the dominating cathedral. As you walk to the station the city becomes a gradual grey, as work beckons, but you are only minutes away from the pretty doll’s houses of our medieval streets and the statues always looking down, pitying those walking beneath them. The city I have lived all my life, the city of study, of Martin Luther, of grand culture uniquely German, and mercifully not bombed. We still had two synagogues, one the oldest in Europe, one a burned-out shell since ‘crystal night’. But no-one now to use them of course. That had happened. The same as everywhere.