Полная версия:

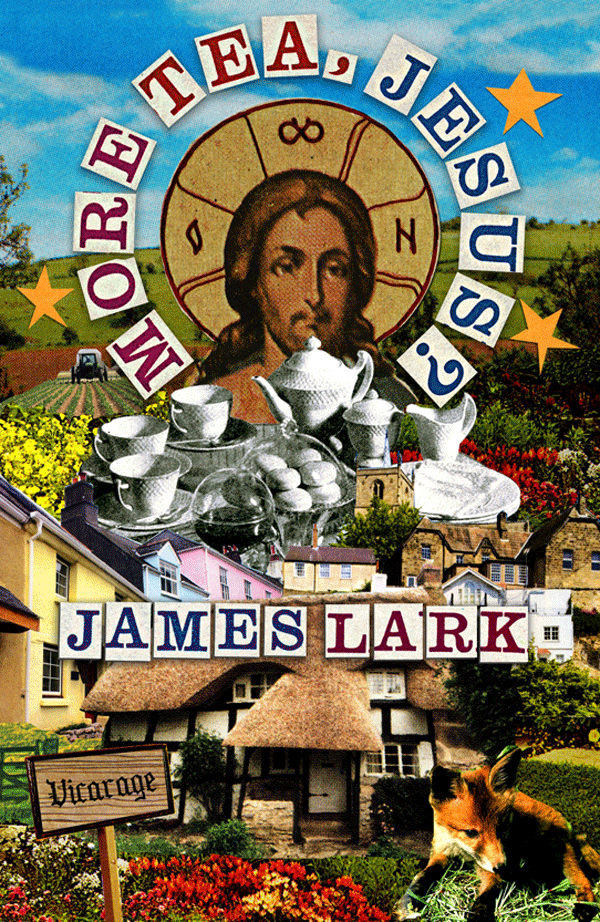

More Tea, Jesus?

More Tea, Jesus?

James Lark

DEDICATION

Dedicated to the memory of Bill Bates, Ian Thompson and Rex Walford. They all would have found weaknesses in my theology and storytelling, but I think they would have laughed.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part Two

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Part Three

Palm Sunday

Holy Monday

Holy Tuesday

Holy Wednesday

Maundy Thursday

Good Friday

Holy Saturday

Easter Sunday

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About Authonomy

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth, and in the firmament of the sky He made two great lights; the greater light was to govern the day and to give light on the earth, and He called it the sun.

Towards the end (which was really just another beginning), the sun was still successfully governing the day (unless you happened to live in Norway, where you might justifiably feel that you had been overlooked) and one day in early spring its golden rays streamed across an unremarkable part of England, winding their way with a vigorous, end-of-winter energy into the unremarkable village of Little Collyweston.

The village was, as its name hinted, little. The one landmark was the parish church of St Barnabas, its plain exterior, wooden door and stained-glass windows lit by the bright, early morning rays. In front of the church a wooden noticeboard stood at a slight angle, dappled sunlight playing over the week’s service times, an advert for the Tuesday Mothers and Children Group and a red piece of cardboard displaying the poorly printed motto:

ASPIRE TO INSPIRE BEFORE YOU EXPIRE!

Somebody in the church had been pinning poorly printed mottoes on the board for as long as anyone in Little Collyweston could remember – so long, in fact, that nobody could remember who was responsible. The incumbent vicar was not greatly keen on the mottoes, but because nobody knew who put them there he wasn’t able to ask them to stop doing it and he didn’t like to remove the mottoes in case he offended somebody, so there they remained, in garish contrast to the plainness of the church.

Even on this bright morning the sun seemed unwilling to penetrate the walls of the building itself. In this respect it had a great deal in common with the inhabitants of Little Collyweston, almost all of whom had more enjoyable ways of spending a Sunday morning than thinking about their creator, so apart from the distant echoes of a sermon floating from the church, the village was still and quiet. The scene might have been the opening to the kind of Saturday-evening post-apocalyptic drama familiar to television audiences in the 1970s. In that instance, the sweetly sinister deserted scenario would have yielded a desperate and low-budget gang of survivors, possibly along with zombies or flesh-eating plants, but when the people living in Little Collyweston finally drew their curtains they would find nothing so dramatic. The most apocalyptic thing to have happened in Little Collyweston was the installation of a new bus stop in 1987.

If the sleeping inhabitants had realised that this was all about to change, they might have been more inclined to venture into the church to get information about the impending day of reckoning. But in the stillness of that clear, bright morning, they would have taken quite some persuading that God had chosen to make any kind of apocalyptic return in Little Collyweston.

Nevertheless, He had, and it had already started.

PART ONE

But of the times and the seasons, brethren, ye have no need that I write unto you. For yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so cometh as a thief in the night.

1 Thessalonians: 5, 1–2

Chapter 1

Reverend Andy Biddle was in the middle of the best family service he had ever devised – and that was quite an achievement by his standards.

If anybody ever understood the peculiarly Anglican tradition of family services, the wisdom was never passed on. These are services which, as their name suggests, are aimed at the whole family, so parents have to put up with having their children with them and everybody else has to put up with having other people’s children with them; nobody, including the people running the services, knows what to do with the children, and the children don’t know what to do with the services, except perhaps ignore them, which results in frequent tellings-off by parents who are invariably guilty of ignoring the services too because everybody, including the people running them, finds them a tedious waste of time. Anglican clergy, not knowing what to do with either the services or the children, often like to ignore them as well, passing all responsibility over to unwary lay readers, trainee priests, or – if they have such a resource to draw on – wives.

Reverend Andy Biddle was an exception. He believed he had a special gift in knowing the level at which to pitch a service for a congregation ranging from the youngest to the oldest people in the church. On this particular day they seemed to be responding even more positively than usual.

He playfully tapped the third egg against the side of the lectern before pulling the shell apart and emptying its contents into a plastic jug. ‘It depends on the size of your frying pan, of course,’ he said, ‘but I find three eggs is usually the right number for a decent omelette.’ He grinned at the rows of faces observing him. ‘Unless you’re very hungry indeed,’ he added, ‘but then, you could always make yourself a second omelette, couldn’t you, now that I’ve shown you how easy it is?’

Andy Biddle’s cookery sermons were a running theme in his ministry. He had first incorporated his love of preparing food into a sermon as a trainee priest, when the vicar at his placement church, not having a wife, had asked him to take responsibility for the family service. Struggling for suitable ways of engaging with disinterested children and distracted adults, he had hit upon the idea of comparing the oats in a flapjack to the church, with God as the sugary content binding the different parts together. It had been a qualified success; enjoyable as making flapjacks in a church service had been, cooking them required an oven (which he realised at the last minute he could not realistically bring into the church itself), and twenty minutes’ cooking time. He had been forced to ask a Mrs Wells, who lived next to the church, to nip home and put his flapjacks in the oven, whilst he preached a somewhat longer sermon than his chosen topic could really sustain.

However, the theory behind the sermon had been a good one, and the flapjacks had been very much appreciated by the younger members of the church. Over the years, Biddle had refined and perfected the technique of preaching with food, specialising in simple dishes he could prepare over a Primus stove (so as to allow the congregation to watch the cooking in process), and simple but memorable messages about the nature of God and the church. There had been some failures; a foolish attempt to make floating islands – a complicated dessert involving meringue which was hard enough to pull off at home – had gone badly awry and the point of his sermon had been lost as a result. Once, whilst preparing beans on toast, his surplice had caught fire, and though it was quickly extinguished and no injuries occurred, his dignity (and with it the strength of what he was trying to say) had suffered badly.

But at best, Biddle’s cookery sermons were inspired and memorable. It gave him no end of pleasure when people at his church, often the very youngest members, would approach him and recall with evident delight the time that he had made spaghetti carbonara, or the minor coup when he had successfully pulled off chocolate brownies in record time, or even – and Biddle knew that special levels of grace were required with children – ‘the one where you caught fire’.

The omelette sermon was his best yet. He had hit upon the beautiful similarity between the broken people of the world and the broken eggs of an omelette. For while the eggs were necessarily broken, what was inside them, when mixed together as one (Biddle was always keen to reinforce the importance of the church as one foundation over the significance of the individual), were the beginnings of a solid, unified body, bound together by the Holy Spirit (that was, the heat in the frying pan). It was an unusually complex message for a family service, but Biddle felt it was an important one and, by using an omelette as his starting point, he was able to make the point of his message far clearer than he would in any run-of-the-mill spiel from the pulpit.

Not only was it a fine sermon, it looked like it was going to turn out to be a very fine omelette.

‘Now we get to the interesting bit,’ he said, watching with gratification as the under-elevens, who had been invited to sit on the floor at the front of the church, leaned forward in a single wave to get a better view of what he was doing. Biddle felt particularly proud that the children in the congregation would be receiving the message in all its complexity. Perhaps, with their childlike perspective, he mused, they might actually understand the profundity of his words more than their parents.

He poured the contents of the jug slowly and stylishly into the frying pan, watching the omelette immediately take shape. Yes, it was going to be an extremely good one. It was just as well: as this was his first family service at St Barnabas, Collyweston, he was keen to make a good impression.

Ted Sloper sat in the choir stalls and watched with increasing disbelief as the vicar’s omelette neared completion. Ever since the nauseatingly cheery vicar had stepped into one of Ted’s rehearsals a month ago and slowly talked the choir through how he would be taking the service, with lots of inane grinning and expressive rises which threatened to take his every sentence into mezzo-soprano territory, Ted had inwardly decided that their new vicar was actually a frustrated Blue Peter presenter. Now Biddle was proving Ted’s theory.

He was showing them how to make an omelette. What next? wondered Ted. A step-by-step guide to making a model of the church using a cereal packet, an empty washing-up liquid bottle and some sticky-backed plastic?

Ted sighed moodily and looked across at the opposite choir stall. The meagre ranks of the St Barnabas church choir mutely watched the culinary activity, glazed looks across their wrinkled faces. It was impossible to tell what they made of it. On consideration, Ted wondered if the omelette was about on their level. He gazed at the grey hair, the balding heads, the reflected stained-glass patterns in the lenses of Harriet Lomas’s glasses, all emerging from a row of tent-like, off-green cassocks worn with the same grace that potatoes wear a sack, and the grim horror of his situation hit him for the seventeenth time that morning. What was he doing in this place? He should be in a cathedral, directing a proper choir, with proper singers – with trebles, for God’s sake, not old women.

Miserably, he turned his attention back to the sacred cuisine that – alas – seemed likely to be the most interesting part of today’s service, and sighed the heavy, desperate sigh of a trapped man. ‘Are you okay?’ asked Harley Farmer, the large bass sitting next to Ted whose singing voice might have made a passable foghorn. Ted looked round at Farmer’s dull eyes and impassive face and decided not to answer.

Once upon a time, he had been a treble in the choir of Winchester Cathedral. He had sung the finest music with the finest conductors. He had projected his own voice up into the heights of the vast, beautiful space of the Cathedral and heard it echoing back from the cavernous arches. What had gone wrong?

Robert Phair was feeling uncomfortably self-conscious. He sat about halfway down the church, a distant smile on his face, trying to look as if he was receiving wisdom, trying to look as if he was happy to be there, and trying to look as if he was entirely unbothered by the fact that his wife had stormed out very noisily and obviously about twenty seconds after Reverend Biddle had broken his first egg. For a moment, every head in the congregation had turned to observe Lindsay Phair’s spectacular exit. A moment later, every eye in the church had fixed on him, sitting on his own in the middle of a pew in the middle of the church. Alone. Embarrassed. He was sure they had all noticed (except perhaps Reverend Biddle, who seemed rather absorbed with his omelette. Mmm, thought Phair, it did smell good – he’d really welcome an omelette right now).

Robert Phair was also sure that everybody in the church felt deeply sorry for his having such a dreadful wife. It wasn’t the kind of sympathy he needed, deserved though it might have been. He loved Lindsay very dearly, but she did have a somewhat impetuous nature and was inclined to overreact, two facets of her otherwise delightful personality which he wished were less obvious at times.

She would be sitting in the car fuming, a sour look of stubborn self-pity on her face. He thought maybe he ought to go to her to show some solidarity in their nuptial bond. He would undoubtedly be in trouble later for failing to stand by her. But, things having calmed down, he didn’t like to remind people of the earlier fuss by leaving the church himself. She would wait for him and they could talk about it later. He was sympathetic with her difficulties, up to a point – after all, Lindsay had been finding it hard coping with the idiosyncrasies of St Barnabas for some time, and the vicar was making an omelette. Still, she maybe should have waited to see what would happen; there was bound to be a meaning to the demonstration. If nothing else, it had reminded him quite how much he liked omelettes.

He shifted in his seat, trying not to look uncomfortable. He hoped Lindsay wouldn’t drive off without him. She wouldn’t drive off, no. She knew he couldn’t walk all the way home with two children.

It was rather disagreeable of her to cause a stir at all, really, however justified. When she was in one of her moods, he often saw exactly what she must have been like as a teenager. All pouty and sulky and – and really not very attractive at all. God help them if Esther and Rebekah turned out like that.

He took in another deep breath and savoured it. He was now experiencing an intense craving for an omelette.

Sathan Petty-Saphon ran the church of St Barnabas. She sat now in her usual seat in the second pew from the front, and was not impressed with what she saw. She was aware that there were churches in which omelettes might be made and nobody would see anything wrong with it. But St Barnabas was not that sort of church. There were standards to uphold. How would Jesus react to somebody making an omelette in his church? Jesus certainly didn’t mess around making breakfast in the Bible.

Things ran in a particular way at St Barnabas, and it often took newcomers a while to get used to it. A new vicar, Sathan Petty-Saphon quite understood, would have a lot of things to get used to, and it would take some time to settle him into the routine of things. But this vicar had been especially slow in adjusting to the way things worked, and didn’t seem to have taken on board either the importance of the things she had made a point of telling him, or indeed the importance of Sathan Petty-Saphon.

She did not run the church in any official capacity. But the running of the church was most definitely her responsibility – that much was surely obvious. She had been careful to mention to Reverend Biddle several times during their first conversation that she had been attending St Barnabas for twenty-six years, almost twenty-seven. She had dropped in titbits of valuable parish information and essential facts about how the church operated.

In spite of this, Reverend Biddle had thus far failed to approach her for advice (though she had made it very clear that it would be freely and gladly given whenever needed); nor had he followed her guidelines regarding the length and style of his intercessions, or indeed who and what to include in them. Her recommendations about keeping ‘unscripted personal additions to the service’ to a minimum had been ignored, as had her counsel that the congregation at St Barnabas always used the traditional version of the Lord’s prayer, with ‘which art’, ‘thy’, ‘it is’, ‘trespasses’, ‘them that’ and ‘for thine be’.

Did she now also have to tell him that it was not, so far as the congregation of St Barnabas were concerned, suitable in the course of a church service to prepare an omelette?

What troubled her was that the omelette was representative of more deep-rooted problems in the new vicar’s approach. The omelette itself, objectionable though it was, was merely a physical manifestation of the spiritual omelette that was cooking in the church. Reverend Biddle seemed determined to cultivate an atmosphere of informality which, if it continued, was going to have an effect on the type of people attending the services. No doubt Reverend Biddle would see people coming into the church – any people – as a good thing. But Sathan Petty-Saphon knew that there were certain types of people who had a negative and potentially destructive effect in these settings. There was Lindsay Phair, for example, flouncing out of the service in that ridiculously self-indulgent way – what exactly did the woman think she was doing? No doubt she thought she was making a statement, as if church was a place for having opinions. It was certainly indicative of Reverend Biddle’s lack of control; under the old vicar, Lindsay Phair would jolly well have sat in silence.

Sathan Petty-Saphon was also worried by a newcomer whom she had seen sitting towards the back of the church in the last couple of services. There was something deeply suspicious about a newcomer who sat towards the back as if they didn’t want to be welcomed. Not having spoken to him, she couldn’t be sure, but she had an instinctive feeling that he was not the type of person they needed at St Barnabas. There was something about the way he sat. He had high cheekbones and facial hair. And always seemed to be pondering things in his head, not just accepting them. The silent, thoughtful type – they often turned out to be the worst kind of troublemaker. Also, he had a slightly Jewish look about him.

She didn’t wish to be ungracious. What would Jesus do, she thought, if he met this man? Probably tell him to have a shave and get a haircut.

She wondered if the man was there now, but resisted the temptation to look round, as the people behind her might think she wasn’t paying attention to the sermon. Instead, she pursed her lips and started to compose a letter in her head to Reverend Biddle as the smell of his omelette wafted agreeably over the congregation.

Many stomachs rumbled. Several people started to wish they had eaten breakfast before church. A few shrewd members of the congregation wondered if the vicar would ask for a volunteer to eat the omelette and began flexing their arm muscles ready to get their hand into the air. (Robert Phair was one of these people, but he quickly reminded himself that his wife had already shown him up this morning and there was a need to be discreet. There were more deserving people in the church, anyway.)

Reverend Andy Biddle was pleasantly aware of the whole congregation holding its collective breath, entranced as the spitting, hissing omelette was unified in the frying pan like the body of broken people that God had drawn together under this one roof.

Outside, the sun had risen. One by one, the other inhabitants of Little Collyweston were getting out of bed and drawing their curtains. Bleary-eyed people stumbled into their kitchens in need of coffee, barely able to appreciate the beauty of the golden rays shining ingratiatingly over their houses. The sun obligingly continued to light up the darkest shadows anyway, spreading its unappreciated happiness over the quiet village.

It didn’t trouble the congregation of St Barnabas church, however. The architect of the building had (presumably unintentionally) constructed it in such a way that actual daylight only rarely made it inside. In the age of electricity, this was not the problem it might once have been, but it did mean that an eternal midwinter stagnated within the church, even on a bright spring morning such as this one.

Perhaps that was the reason why so few people ever seemed to be happy at the Sunday-morning services.

Everything had gone according to plan – the omelette had been as fine a specimen of an omelette as Biddle ever expected to see, and according to the four or five children who had consumed it in a matter of seconds, it also tasted jolly good. But Reverend Biddle couldn’t quite rid himself of a feeling of unease following his sermon. He thought it had been well-received, but there was a definite atmosphere amongst the congregation which suggested that it might not have been understood as well as he had hoped. Perhaps it was only his imagination, but there was a definite anxiety in his own heart that he couldn’t put aside.

He continued with the service, smiling as much as possible so as not to give away his discomfort. It was halfway through the intercessions that the reason for his unease dawned on him: brilliant though the omelette had been in a culinary sense, in the excitement of his achievement he had completely forgotten to tell the congregation what it meant. He had left out the explanation. In short, he had delivered a perfect sermon about how to make an omelette.

No wonder they looked so baffled.

Hastily, he inserted a long intercession in which he thanked God for his ‘binding love, which binds and unifies our broken lives to make us a single unified body, just as broken eggs are bound together in an omelette …’ But he felt fairly certain that this was lost on the congregation. Too little, too late.

Sheepishly, he announced the final hymn. As the organ piped up with an almost completely different set of notes to those the composer had written, Biddle began to formulate plans for a series of sermons in which he could unpack and expound upon the significance of his perfect, family-oriented and utterly irrelevant omelette.

Chapter 2

Sunday lunch in the Phair household was tense as usual. Something about spending the morning at St Barnabas church always cast a nasty atmosphere over the rest of the day; in particular, it put Lindsay in a miserable mood. Today her mood had taken a rather extreme turn for the worse.

They had driven home in silence (apart from the chattering of the girls in the back of the car, who had eventually been told to shut up by Lindsay, which had made Rebekah cry). Lindsay had prepared lunch without speaking, but made her disposition clear by banging the cooking utensils as loudly as possible, as Robert had tried to sound interested and not jealous at the girls’ description of what the omelette had tasted like, whilst acting as though their mother’s behaviour was completely rational and only to be expected on a Sunday afternoon. Lunch was served in plate-banging silence.