скачать книгу бесплатно

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Dramatis Personae (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

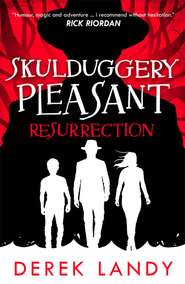

The Skulduggery Pleasant series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_9c20e075-35a5-533f-8918-4343c95a88ee)

A new beginning.

That’s what this was. A fresh start. He was going to deliver this one piece of information and then leave. He could go home, back to New York, or maybe Chicago, or Philly. Ireland didn’t suit him any more. He was done with it – and it, apparently, was done with him. He was OK with that. He’d had some good times here. He’d had some fun. He’d made some friends. But a new day was about to dawn. All Temper Fray had to do was survive the night.

The wall up ahead cracked. By the light of the streetlamps, the cracks spider-webbed. Any last vestige of hope that he’d just be able to walk out of here vanished with those cracks. Temper had seen this trick before. A redneck psycho called Billy-Ray Sanguine used to jump out at people as they passed, kill them before they blinked. Temper had met Sanguine once. For a hillbilly hitman, he’d been all right. Whoever this guy was, he was no Billy-Ray.

The wall spat out a skinny little runt who came at him with a big knife and a bigger snarl. Temper ignored the snarl for the moment, focused on the knife, batting it away and slamming an elbow into the runt’s mouth, dealing with the snarl almost by default. The runt went down, all flailing limbs and broken teeth, and Temper hurried on.

Yep. Things were going badly. But of course they were. Nothing ever went well for Temper Fray.

A motorbike came round the corner ahead of him, its single headlight sweeping the storefronts, and slowed almost immediately. Temper kept walking, keeping his head down, his hands swinging loosely by his sides. The guy on the motorbike wasn’t wearing a helmet, and he wasn’t looking at Temper. He was focused on the road, keeping his head straight. Just a guy on his bike, that’s all, going about his business. As he drew parallel, his right hand drifted into his jacket.

Temper lunged, shoving him as he passed, and the bike toppled and the driver cried out as he fell. Temper kicked the consciousness right out of him and the guy flattened out. Bending over him, Temper reached into his jacket, found the gun and pulled it free. He checked it was loaded, then flicked off the safety. His own gun was on the kitchen table in the house he’d been staying in, alongside his phone. He’d have traded all the guns in the world for his phone right now. What he wouldn’t give for a chance to call in reinforcements.

What he wouldn’t give to call in Skulduggery Pleasant.

He hurried down a side street. There was a woman walking towards him, silhouetted by the lights, her shadow stretching long and thin over the cobbles. He couldn’t see her face. It could be Quibble or, worse still, Razzia, or it could just be another citizen of Roarhaven going for a late-night stroll through the city. Temper held the gun behind his back and kept walking.

They drew closer. The gun felt slippery in his grip. He went left and so did she, and it was only when they passed each other that he glimpsed a face he didn’t recognise. She gave him a courteous nod and he returned it, and they walked on and he breathed in relief.

“Excuse me,” the woman said behind him, and he turned just as a shadow detached itself from their surroundings and snapped the woman’s neck. She crumpled and Razzia stepped over her body.

“Thirteen,” Razzia said in her broad Australian accent. “Thirteen innocent bystanders. I’m not saying I’m breaking any records, but you gotta admit that’s impressive.” She looked up, smiling brightly. Beautiful, blonde, always dressed in tuxedos, Razzia was also completely and utterly insane. “You have been a naughty boy.”

Her hand flashed up and Temper ducked, hearing tiny teeth snapping beside his ear. He glimpsed the black tendril retracting into Razzia’s palm like a nightmarish tape measure and fired at her, but she was already sliding back into the shadows. There was someone behind her, striding up. A bald woman with a gun. Quibble.

She opened fire and he kicked a door open and fell inside, more bullets peppering the doorframe after him. Inside there was a man leaping off a couch and a woman with two mugs of coffee in her hands, staring at him in shock as he barged past her. Temper ran into the next room, saw two men through the window and turned back, took the stairs. The couple shouted and raced after him, and now he could hear a baby starting to cry. He ignored it, hurried to the master bedroom, and through the wide-open curtains glimpsed a young man on the rooftop opposite. Thin, with shockingly platinum hair. Nero. Temper blinked and the young man was gone.

“Dammit,” Temper muttered.

He sprinted to the window and then Nero was beside him, sticking his foot out, and Temper tripped and collided with the wall. He twisted, bringing the gun up, but Nero was suddenly right next to him, snatching the weapon from Temper’s hand before vanishing again.

Temper had a full second to get to his knees before Nero teleported back into the room, gun aimed squarely at Temper’s chest. This time he’d brought a friend, dressed in black, a uniform of rubber and leather. The mask he wore covered his whole head. Not even his eyes were visible behind those tinted lenses.

“Hey, Lethe,” said Temper, slumping back and offering a feeble wave. “What’s going on?”

Lethe observed him for a long few seconds. When he spoke, his voice was that familiar hollowed whisper that picked over every word with undisguised relish. “I knew you were never truly one of us.”

Temper shrugged. “Easy to say with hindsight …”

“I could see it in your eyes,” Lethe said. “Despite your protestations, despite your wild claims, you didn’t hate the mortals nearly enough.”

“Well,” Temper said, resting his back against the wall and crossing his legs at the ankles, “I’ve always had trouble hating people because they’re different than me. It’s a black thing; you wouldn’t understand. Or maybe you would. Could there be a brother hiding beneath that freaky mask of yours?”

There was movement out on the landing, and Lethe stepped aside as Razzia sidled in. Memphis and Quibble shoved the young couple into the room behind her.

“Look who we found downstairs,” Razzia said. “More innocent bystanders.”

“Please,” the guy said. “I … I don’t know what’s going on, but we’re not a threat to you, I swear we’re not. I’m – listen to me, we’re both Arborkinetics. We have a child in the other room, please let us—”

“What’s an Arborkinetic?” Memphis asked, his lip curling while he pressed his gun against the young woman’s head.

“Plants,” said Quibble. “He talks to plants. Makes them grow.”

Memphis laughed and said, “Man, that’s dumb,” which was rich coming from a guy who dressed like Elvis.

“Plants,” said the young man. “Exactly. We can’t hurt you. If you let us go, we’ll—”

Quibble raised her gun to shoot him in the head, but Lethe held up a hand. “Ah-ah,” he said. “They may talk to plants, but they’re still sorcerers. They’re still part of the family. We don’t kill family unless we absolutely have to.”

“Thank you,” the guy said. “Thank you so much.”

“Hey,” Lethe said, “we’re all on the same side.” The baby started crying again, and Lethe glanced at Quibble. “Kill the child.”

The young couple immediately tried to break free, but Razzia hit the guy so hard his legs gave out and then grabbed the girl, held her in a choke.

Lethe didn’t take his gaze off Quibble. “You’re still standing here. The child is annoying me. Kill it.”

Quibble had now gone quite pale.

“I’ll do it,” Razzia said happily, but Lethe shook his head.

“No,” he said. “I instructed Quibble to do it, so Quibble will do it.”

Quibble didn’t want to do it. “Please,” she said, her voice soft. “It’s just a baby.”

Lethe observed her through the tinted lenses of his mask. “I see.”

Tears in her eyes. “Lethe … come on, please …”

“You, ah, are refusing to obey, Quibble?” Lethe asked.

Memphis glanced away, refusing to meet Quibble’s eyes. Nero looked bored, while Razzia watched with growing enjoyment, completely oblivious to the fact that the young woman she was choking had passed out.

“I can’t kill a kid,” Quibble said quietly.

Lethe took a moment. “Oh, dear.”

She was dead. She knew it. Temper had seen that look before, that doomed expression on a slackening face. In his experience, there were only three possible options open to her at this point. The first was to run, but Lethe had a Teleporter on his side, which kind of ruled that out. The second was to give up: to accept what was coming or start begging. But begging wasn’t Quibble’s style. Quibble was an Option Three kind of girl.

She raised the gun, aimed it straight at Lethe’s face. Immediately, Memphis raised his, pressing the muzzle to Quibble’s temple.

“Don’t,” Memphis whispered. “Don’t you do it.”

“This is exciting,” Razzia said, and clapped her hands. The young woman slumped to the floor, unconscious.

“This is unfortunate,” said Lethe. “Very, hugely, unfortunate.”

“I can’t murder a baby,” Quibble said.

“Babies are just people who haven’t grown up yet. You’ve killed loads of people. Loads.”

“So let’s wait eighteen years and I’ll kill this one,” said Quibble.

“Oh,” said Lethe. “Oh, this is one of those … principle things, isn’t it? That’s … that’s sad. I’m sad now. You’ve made me sad. Because now I’ll have to kill you, Quibble, and … and I would prefer not to.”

His hands flashed, stripping the gun from Quibble’s grip and turning it back on her, pulling the trigger before she knew what was happening.

Her body toppled backwards. The wailing from the other room got louder, and Lethe handed the gun to Razzia. She looked at it like it was a piece of rotting fruit, and tossed it away.

“I’m sorry,” Lethe said to Memphis. “I know you were close.”

“She was my sister,” Memphis said.

“Oh,” said Lethe. “Didn’t know you were that close. I feel I have to ask, though, Memphis, and please, try not to take offence. Are you going to try and kill me for this? To exact revenge?”

Memphis looked down at Quibble’s body. “No, I guess I’m not,” he said at last.

“Good,” said Lethe. “That’s good. It’s best, after a family tragedy, that everyone tries to move on, and put the past where it belongs. In the past.”

“Do you want me to kill the baby?” Razzia asked hopefully.

“What baby?” Lethe said, and turned back to Temper. “You’re coming with us, Mr Fray. We have questions to ask.”

Another man entered the room, a guy with a braided goatee. Temper tried to keep him away but one touch was all it took, and all the bad thoughts Temper had ever had swirled and swarmed and swamped his mind.

2 (#ulink_fb0734fd-f588-5b8a-8c3d-f0b9c65ff975)

When the bad thoughts crept up on her, and they did, they came slowly and quietly, slipping in unbidden to the back of her mind, and there they waited, patiently, for her to notice them.

She viewed them as if from the corner of her eye, hesitant to acknowledge their arrival and powerless to make them leave. They stayed like unwelcome guests, filling the space they occupied and spreading outwards. They slowed her down. They dragged on her, made her heavy. When she walked, her feet clumped. When she sat, her body collapsed. It was hard getting out of bed most days. Some days she didn’t even try. She knew what was coming.

She was going to die. And she was going to be on her knees when it happened.

She couldn’t see her death, but she could feel it. Kneeling down to change a car tyre, she had felt it. Kneeling down to clean up after she’d dropped a plate, she had felt it. Kneeling down to play with the dog, she had felt it.

This is how I’m going to die,she’d realised. On my knees.

And always, always, after this had occurred to her there came another thought, the thought that it had already happened, that she was already dead, that her body was growing colder and her blood wasn’t pumping any more. She experienced moments of pure terror when she believed, believed with everything she had, that she was trapped in her own corpse, that nothing worked and that no one could hear her screaming.

And then she moved, or she breathed, or she blinked, and with each new act of living she clawed her way back to the realisation that no, she wasn’t dead. Not yet.

It was mid-afternoon, and it was cold. The cold meant something. It was the last bite of the beast called winter, a beast that had stayed too long already. She could feel it on her face, on her ears; she could feel it seeping through her clothes. It meant she still had a spark of life flickering inside her. That was good. She needed that. But it also signalled a loss of focus, as she found it increasingly difficult to summon the crackling white lightning to her fingertips.

Eventually, she just sat on the tree stump on which she’d placed the tin cans she’d been using as targets. Three of them were scorched. Two were brazenly untouched. Still, three out of five meant that at least her aim was improving.

She hugged herself. It was an old hoody, but she liked well-worn clothes. Her jeans were a state, and she’d forgotten what colour her trainers had once been, but they were comfortable, and more importantly they were her. Lately she’d needed reminding of just who that was.

She looked at the trees. Looked at the sky. Got her mind away from her thoughts. Her thoughts weren’t kind to her. They hadn’t been for quite some time now. She looked at the twigs on the ground. They were dry. It hadn’t rained in two weeks. A rarity for an Ireland still locked in winter’s jaws. She watched a beetle scurry beneath a leaf, caught up in its own little life. To the beetle, she must be a vast, unknowable thing, a hazard to be avoided but not overly concerned about. If a god is going to step on you, it’s going to step on you. You’re not going to waste your little beetle-life worrying about something you have no control over.

She looked up, half expecting to see a giant foot descending, but the sky was blue and clear and free of gods. She waited, nonetheless.

Then she stood, and took the trail back through the trees. She used to walk this path as a child, side by side with her uncle. They talked about nature and history and family and he told her stories and she did likewise. They competed as to who had the goriest imagination, but even when he conceded defeat, with a look of mock-horror on his face, she knew he was holding back. Of course he was. Gordon was the writer of the family.

She remembered walking through this woodland with him. She could recall, quite distinctly, as if looking at a photograph, the angle at which she’d seen him. She was small and he was a grown-up, and his hair was brown and thinning where hers was long and black, but they had the same eyes, the same brown eyes, and when he laughed he had a single dimple, just like she did. It had been twelve years since Gordon had been murdered, twelve years since she’d tumbled into this twilight world of sorcerers and monsters and magic. She’d been twelve when it happened, not even a teenager when she’d started her training. The years, they had thundered by, heavy and unstoppable, a boulder rolling downhill. Bruises and broken bones and bloody knuckles and screams and laughs and tears. A lot of tears. Too many tears.

The house Gordon had left her sat on the hill, visible through the trees ahead. Even after it had officially passed into her ownership, she had been unable to think of it as anything other than Gordon’s house. Every room, and there were many, reminded her of him. Every Gothic painting on the walls, and they were plentiful, brought to mind some comment or other he had once made about it. Every brick and piece of furniture and bookcase and floorboard. It was Gordon’s house, and it would always be Gordon’s house.

Then she’d gone away. Five years she’d spent on a sprawling farm on the outskirts of a small town in Colorado. She had a dog for company, and occasionally company of the human variety, but she kept that to a minimum. She didn’t want to be alone with her thoughts, but she deserved to be. She deserved a lot of horrible things.