Полная версия:

The Red Dove

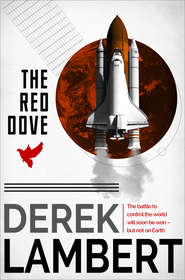

THE RED DOVE

Derek Lambert

COPYRIGHT

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1982

Copyright © Derek Lambert 1982

Design and illustration by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780008268428

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2018 ISBN: 9780008268411

Version: 2017-12-20

RED ALERT!

Dove lurched violently to one side when it was seventy-five miles above the earth.

A beam weapon, Talin guessed, gripping the hand controller. Not a direct hit but it must have passed within a few feet of the fuselage.

Dove began to turn on her side, shuddering.

Talin fought the manual controls. Dove settled again, then suddenly dipped her nose.

Talin pulled, coaxed, shouted; but his arms were as heavy as lead as the earth pulled at them and his reactions were as slow as a drunk’s. Gradually Dove raised her beautiful, aristocratic nose. And it was then that Talin noticed that the red light beside the unconscious body of Sedov was glowing red. The bomb in the cargo bay must have been primed by shock waves from the beam.

Down plunged the Dove. With enough nuclear power inside her, Talin thought, to devastate a city. His brain froze. His head slumped forward …

DEDICATION

For Frank and Marsha Taylor,

friends and advisers

EPIGRAPH

The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror.

T. S. Eliot (1888–1965)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: Scenario

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Part Two: Treatment

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Part Three: Script

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Part Four: Première

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Keep Reading

About the Author

By The Same Author

About the Publisher

PART ONE

Scenario

CHAPTER ONE

The absurd possibility that he, a Hero of the Soviet Union, could ever become a traitor occurred to Nicolay Talin when he was 150 miles above the surface of the Earth.

The absurdity – it was surely nothing more – was prompted by an announcement over the radio link from Mission Control:

‘We know that you will be proud to hear that at 05.00 hours Moscow time units of the Warsaw Pact Forces crossed the Polish border to help their comrades in their struggle against the enemies of Socialism attempting to subvert their country.’

Proud? Involuntarily, Talin shook his head. Such timing! While he was acting as ambassador of peace in space the Kremlin had perpetrated an act of war on Earth.

‘So they finally did it,’ was all he said.

He felt Oleg Sedov, Commander of the shuttle, Dove 1, on its maiden flight, appraising him. Sedov, forty-seven years old and as dark and sardonically self-contained as Talin was blond and quick, had been appraising men all his adult life.

Sedov, separated from Talin by a console of instruments, leaned forward in his seat, cut the radio and smiled at Talin.

‘You didn’t exactly glow with patriotic fervour,’ he remarked.

Talin gazed at Europe, bathed in spring sunshine, sliding away below them. There was a storm gathering over the sheet of blue steel that was the Mediterranean; to the north lay a pasture of white cloud; beneath that cloud was Poland, beneath that cloud war. In ninety minutes they would be back, having orbited the Earth. How many would have died during that time?

He tried to relax, to banish the spectre of treachery that had suddenly presented itself. True, he had often doubted before; but his doubts had never been partnered by disloyalty. He unzipped his red flight jacket and said: ‘You know better than I do, Oleg, that what goes on down there,’ jabbing a finger towards an observation window, ‘doesn’t have much impact up here.’

‘So you’re suppressing your joy until we land?’

‘If we land,’ said Talin who was piloting Dove.

‘Ah, there I share your doubts. But let’s keep them to ourselves,’ Sedov said, re-activating the radio.

‘Dove one, Dove one, are you reading me?’ The voice of the controller in Yevpatoriya in the Crimea cracked with worry. When Sedov replied his tone changed and he snapped: ‘What the hell happened?’

Sedov shrugged at the panels of controls, triplicated in case of a failure, and said: ‘Just a temporary fog-out. Also I had to use the bathroom.’

The controllers had long ago learned to accept Sedov’s lack of respect: not only was he the senior cosmonaut in the Soviet Union, he was a major in the First Chief Directorate of the KGB.

‘Is everything still going according to schedule?’

‘Affirmative,’ Sedov replied.

‘We were worried about Comrade Talin?’

Sedov frowned. ‘He looks healthy enough from where I’m sitting.’

‘His heart-beat went up to a hundred and twenty just now.’

Again Sedov’s dark eyes appraised Talin as he said to the controller: ‘Maybe he was thinking about Sonya Bragina.’

‘That,’ said the controller, ‘is a remarkable observation, because it so happens that we have Sonya Bragina here waiting to talk to Comrade Talin.’

This time Talin himself felt his pulse accelerate as he heard Sonya’s voice, pictured her at Mission Control, wearing her severe, dark blue costume to make her look more like a Party member than a dancer, blonde hair braided and pinned – remembered her the last time he had seen her, naked on the bed in her apartment in Moscow.

What was happening was obviously the dream-child of a Kremlin publicist. Bolshoi ballerina converses with lover in space; as subtle as a Pravda editorial but more effective. And if Dove 1 crashed into the Siberian steppe then the Russian people would always remember the last, space-age conversation and weep delightedly.

Ironic, he thought, that at this historic moment I should be hurtling towards the United States of America.

‘Hello, Nicolay, how are you?’

‘I’m fine,’ he said.

‘Where are you now?’

‘Right above you.’

‘Your mother sends her love. And –’

‘Yes?’

‘I love you.’

Talin guessed that someone had prompted her because, although she was by nature passionate, she wasn’t demonstrative in public, certainly not for the benefit of the millions watching and listening on television and radio.

Now he was expected to respond: ‘And I love you,’ but he rebelled because the whole exercise was so gauche; there was nothing they could do about that and she would understand.

He said: ‘Do you know what I fancy now?’

A nation held its breath. Sedov raised an eyebrow.

Talin said: ‘A plate of zakuski, salted herring perhaps with beetroot salad, followed by a steak as thick as a fist washed down with a bottle of Georgian red.’

He thought he heard her laugh but he couldn’t be sure; the laugh would be surfacing all right but she had the discipline to fight it back. Anyway, their audience would appreciate the remark: a man wasn’t a man unless he indulged his belly.

She hesitated, the Kremlin script in tatters. ‘Aren’t they feeding you all right up there, Nicolay …?’ Her voice faded as she realised that she had made a mistake, implied criticism.

He came to her rescue. ‘I was only joking. The food’s fine.’ Well, not bad, if you liked helping yourself to re-hydrated vegetable soups, blinis and coffee in slow motion to combat weightlessness.

‘I miss you, Nicolay.’

Another cue. He ignored it.

‘Ten more orbits,’ he said, ‘and we’ll be down.’

‘Goodbye, Nicolay.’

‘Goodbye, darling.’ Sweet compromise. ‘Don’t forget the zakuski.’

And she was gone.

‘Well,’ said Sedov, ‘I didn’t realise I was in the presence of a great romantic.’

‘I’m not a ham from Mosfilm,’ Talin told him.

Even that was a perversity: Mosfilm made good movies. Perhaps space had got to him; it could cause disorientation, which was why cosmonauts underwent so many psychological examinations.

That would explain his aberration when he heard about the invasion of Poland. A side effect of the transition into space, awareness of the curve of the globe below and the void above.

The Soviet Union occupied a sixth of the world’s land but in orbit he had seen the other five sixths. The pendulous sacks of South America and Africa, oceans scattered with fragments of land … Space and freedom had become one, the breeding ground of fantasy.

Beneath them now was the cutting edge of the United States. In eleven minutes thirty-eight seconds they would have crossed the North American continent. Dove had reached the Mid-West when another irrational notion presented itself unsolicited to Talin: what would happen if, because of a malfunction, they were forced to land in America?

Far away in the Crimea one of the scientists monitoring the shuttle reported that Talin’s heartbeat had increased to 125.

When darkness returned to Earth, when, that was, the globe was between Dove and the sun, the disturbing spectres fled, the reverse of the norm on earth when the fantasies of night vanish with the dawn. And Talin and Sedov began to prepare for their return to Mother Russia.

Both shared one doubt about the shuttle: they feared that, like the spaceship destined for Venus that had exploded on the launch-pad in October 1960, killing Field Marshal Mitrofan Nedelin and scores of technicians, it had been put into production too quickly.

The Kremlin was obsessed with firsts. The first satellite into space, Sputnik 1 in 1957, the first man in space, the late Yuri Gagarin in 1961. They had been mortified when, in 1969, American astronauts had made the first landing on the moon, paranoic when, in April 1981, the Americans had soft-landed their shuttle Columbia in California.

That achievement had heralded the dawn of an age when Man could commute in space, when passengers could visit floating hotels and return home in a winged ship that looked like an ordinary jet airplane – a ship that could be used time and time again.

It had also heralded the possibility of a titanic power struggle. With a shuttle a super-power could deposit convoys of spy satellites in orbit equipped with beam guns and telescopes that could sight a kopek coin 400 miles away.

The Russians had been poised to launch this new age but they had been beaten to it by the Americans who had also had the gall to make the launch on 12 April, 1981, the twentieth anniversary of Gagarin’s first orbit.

So they had postponed the launching of their prototype scheduled for 18 January, 1982, and concentrated on another first: building a fleet of space trains modified to construct, rather than merely deposit, stations in space.

Fears that the Kremlin was dangerously obsessed with the race to overtake the US initiative were realised in September 1982 when the first unpublicised launch aborted on blast-off.

There were two more trials, one successful, one not, before Dove 1 finally went into orbit with Sedov and Talin at the controls on 9 May 1983, Victory Day. Not all the refinements had yet been incorporated; but the Kremlin could boast that it possessed the command ship of its construction fleet in space.

The military potential of Dove, including some of the refinements, was the responsibility of the Commander, Sedov. Talin accepted that it would have to be armed: you had to defend yourself. But, projecting the dreams of his youth into the firmament, he saw himself as a pioneer of peace in space.

And the Kremlin backed him. Having accused the Pentagon of building Columbia to lay a trail of nuclear mines in orbit they assured the world that their aim was the peaceful exploration of the heavens.

Dove not Hawk.

The red and white ship looked much the same as its American sisters. It was 190 feet long with swept-back wings and brutish engines in its tail; on its back it bore a cargo bay with a capacity of forty tons, ten more than Columbia; in its inquisitive-looking nose there were three decks – storage area, living quarters and flight deck.

It was to the living quarters, as Dove 1 orbited at 18,000 mph on this May day in 1983, that Talin now walked with ponderous, weightless steps to prepare for re-entry.

On one side was a bathroom, on the other bunks and lockers, in the centre a table. From the dispenser Talin took a small tray wrapped in plastic marked Day 3, last meal. Into the dehydrated food inside he squirted water through a hollow needle attached to a faucet; then he removed the plastic, clamped the tray to the table and slowly began to eat cold beef and potato salad.

He drank a glass of synthetic orange – it was impossible to re-hydrate natural orange because water and crystals don’t mix – took off his flight jacket and put on an anti-gravity suit with inflatable trousers. The pressure of the oxygen on legs and belly in these stopped the blood from plunging to the lower extremities: puncture those pants and you blacked out.

Back in the flight deck Sedov had prematurely begun the pre-burn check-out. It was only Talin’s second trip into space but he had spent 300 hours in a simulator and he knew this was unusual for a veteran such as Sedov. Talin shivered and glanced into the star-strewn darkness for comfort.

Sedov was sitting on his high-backed seat, one hand on the rotational hand controller, staring at the computer screen. He was frowning.

‘What’s wrong?’ Talin asked.

‘I wish I knew. She just doesn’t feel right. Maybe space is getting to me.’ Sedov stood up. ‘You take over the check-out while I get into my anti-gravity gear.’

As he plodded away Talin strapped himself into the seat next to Sedov’s and examined the indicator lights, computer readouts, dials. Nothing wrong there. And yet … Sedov’s concern was contagious.

Sedov who had circled the moon, Sedov who had spent ninety-six days on a SALYUT space station, Sedov the laconic cosmonaut/intelligence officer who had been personally chosen by Nicolay Vlasov, Chairman of the KGB, to represent the MPA, which maintained Party control over the military, in space. Hardly the sort of man to be fanciful.

What worried most cosmonauts was their reliance on computers. If a computer could foul up your electricity bill then it was perfectly capable of abandoning you with only manual glide control over the Pacific Ocean.

Figures on the screen in front of Talin danced with blurred speed.

Sedov returned, strapped himself into his seat and slipped on his white helmet and headset. His lean, Slav face was expressionless as he spoke to Control.

Turning to Talin, he said: ‘We’re just half way round the world from touch-down.’

Green light shone below them, gaining strength by the second. They were over the Atlantic which was just emerging from a night blanket of cloud.

Again Sedov disconnected the radio link. ‘Stop thinking about Poland,’ he said. ‘They had it coming to them.’

‘I wasn’t thinking about Poland,’ although his doubts had begun with the announcement of the invasion.

The trouble was that Sedov, his mentor, knew him too well. Read his thoughts. Sedov had known him when he was a young rebel and because he admired his talent for space navigation, because he had no son of his own, had taught him to quell – not kill – the rebellion. He had also persuaded Military Intelligence, GRU, even then little more than an arm of the KGB, that he was politically acceptable.

In a way Sedov’s insight into his own reactions was another conscience. To betray Communism, even in thought, was to betray Sedov.

At 06.00 hours, one hour before the scheduled landing, Sedov, having re-contacted Mission Control, nodded at Talin and said: ‘It’s all yours.’

It was the crucial moment, no abort possibilities after this. Forget Poland, forget Sedov’s doubts.

First Talin had to reduce the impetuous speed of Dove. He turned her round and ignited the retro-fire engines. She quivered, slowed down and, with the two small engines thrusting forward, began to descend backwards towards the Earth’s atmosphere. A dozen dangers now lurked in her straining body. If, for instance, the skin of ceramic tiles protecting her from heat peeled off she would explode into a ball of fire.

After the retro-burn that took Dove out of orbit Talin turned her round again and pulled up her nose; inconsequently, he remembered pulling the reins on a recalcitrant horse he was riding as a boy on the steppe.

Their altitude was now seventy-five miles. The temperature on the outside of Dove was between 2,000 and 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit. As the melting point of aluminium, from which her body was made, was 1,200 degrees they couldn’t afford to lose many ceramic tiles. In front of them the air glowed with heat.

As Dove dipped towards the land masses of Europe and North Africa and the Earth’s gravity began to pull, Talin’s arms felt heavier and he became weighted to his seat.

He checked the instruments. They were 3,000 miles from the landing strip which was itself 100 miles north of the launch pad at Tyuratam in the Soviet central Asian republic of Kazakhstan.

Talin spoke to Control to reassure them. Not that there was any real need because every reaction of Dove was monitored on forty-eight consoles. Even my heart beat, he remembered.

‘Everything under control,’ he reported. ‘I reckon I can see Russia ahead and that’s always a beautiful sight,’ which it was; he only wished that, being a Siberian, they were homing down from the East Coast, over the Sea of Okhotsk with the fish-like body of Sakhalin Island beneath.

He glanced at the digital clock. In less than half an hour they would touch down on the established flight path. Sedov had been wrong: there was nothing wrong with their beautiful red and white bird. Talin gave a thumbs-up sign to Sedov.

Which was when the radio link with Mission Control went dead.

Don’t panic. Talin’s preparation for any emergency in the simulated shuttle on the ground asserted itself. Controlled panic. His arms felt even heavier than they should, a rivulet of sweat coursed down his chest.

He glanced at Sedov. Sedov was smiling. Smiling!

Sedov spoke into his mouthpiece: ‘You can hear me?’

Talin nodded, remembering as Sedov spoke.

‘The black-out we anticipated,’ Sedov. ‘You were prepared for it?’

‘Of course, the heat …’ The lie stood up and took a bow; Sedov ignored it because that was his way and said: ‘It won’t last long.’

When Control returned Talin suppressed the relief in his voice. At 250,000 feet he began to fly the ship a little, using elevons, brakes, rudders and flaps, correcting flight path and speed.

At 80,000 feet over the Sea of Aral the engines cut and, as planned, Dove became a glider. From Control: ‘Perfect ground track.’

They were wrong. At that moment the shuttle veered sharply away from the runway laid out like a white ceremonial carpet. Talin took over completely from the autopilot and tried to correct the flight path. Nothing. Panic returned but was instantly disciplined, a wild dog on a lead.

Beside him Sedov was also struggling with the dual hand controller and rudder pedals. But the Dove had become a wilful bird of prey that had sighted a far-off quarry.

Sedov’s face was a mask, a single muscle dancing on the line of his jaw. He said: ‘This is crazy,’ and Talin knew what he meant: rockets, computers, all the most sophisticated technology that Man could devise had worked, but elementary controls used by any weekend glider pilot had failed. That was Russia for you.

They were below 50,000 feet, supposedly descending for the final approach and landing on a twenty-two-degree glide slope.

Sedov took over and raised the Dove’s nose. As they headed away from the strip in a wide arc he said: ‘I once had a car like this.’

His voice calmed Talin. ‘A car?’ He peered down. A ten-mile radius around the strip had been levelled in case of a forced landing; beyond this circle of black earth and shale lay the desolate steppe still patched with snow.

‘Sure a car. It wasn’t much of a car, an old Volga that looked like a tank. And it developed this trouble, it would only steer in one direction.’

From Mission Control came a hoarse voice: ‘What’s going on up there?’ Talin could picture the consternation as both screen monitors and visual trackers reported Dove’s deflection.

‘A minor technical fault,’ Sedov said.

‘At this stage?’

‘This bird doesn’t want to return to its cage,’ Sedov said.

Talin noticed that he was no longer trying to correct the flight path of the shuttle.

‘What the hell are you talking about?’

Sedov cut the radio link.

He said to Talin: ‘About that old car of mine. I was lecturing at Moscow University in those days but I lived in lodgings off Russakouskaya Street. Now as you know that’s on the other side of the city but in a direct line –’

‘I don’t see …’

‘You will, you will.’ The lack of noise was eerie and Talin wondered again if space had at last affected Sedov. What sort of impact would 100 tons of spaceship make on the steppe? They could always eject – but only to disgrace; in any case Sedov would never permit it. ‘You see,’ Sedov was saying, ‘all I did was to drive in a semi-circle round the city until I arrived at the University.’ He leaned back in his seat. ‘There,’ he said, ‘now you take this old Volga back to base.’