скачать книгу бесплатно

‘Perhaps you’ll show me more of your Moscow. The city foreigners never see. I remember as a kid on the waterfront in Boston there were some slot machines. You fed them a nickel and a tableau came to life. A circus, a rodeo, that sort of thing. That’s the Russia foreigners see. Feed Intourists with hard currency and the tableaux come to life. But with you I have a passport ….’

‘You have Soviet citizenship, an internal passport. You’re free to travel.’

‘You know that’s not true.’

She gave a shrug, a dismissal. ‘Perhaps one day ….’

Calder said goodbye to Katerina’s parents. ‘But the party’s only just beginning,’ Sasha objected. He sung a few bars of the Volga Boatman. ‘The song all Americans know.’ Calder braced himself for Sasha’s handshake but it was limper this time, emasculated by firewater.

Calder left.

Outside the cold embraced him like an old friend and sent the vodka coursing through his veins. With a skull full of fancies he made his way on rubber knees to the Zhiguli in the parking lot.

The cream paint on the battered Volga that followed him shone silver in the moonlight.

When he got back to his apartment off Gorky Street Calder found Jessel from the American Embassy waiting for him.

Jessel, a New Yorker, was his link with the United States: he was one of Jessel’s links with the Soviet Union. Jessel worked for the Commercial Counsellor. He was middle-aged with amiable features and a soft voice and thin, ear-to-ear hair. He didn’t look at all like a spy and that was his strength.

He pretended to like Calder but from time to time Calder caught a frayed glance and he knew that Jessel was thinking: ‘How can you have done it?’

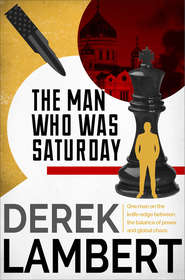

To make things easier for themselves they played chess.

For Calder chess was his therapy. It gave him direction. He believed it to be the distillation of human behaviour encompassing prodigious foresight, petty opportunism, grand strategems, puny deceptions and glittering combinations that could fail because of a single unsighted flaw. Moreover chess was the honed product of centuries of trial and error, a diamond made of compressed genius.

Jessel, who had the key to the apartment, was sitting in front of a crowded chess board drinking bourbon.

‘Make yourself at home,’ Calder said.

‘And where,’ Jessel asked, moving a white pawn, ‘have you been making yourself at home?’

‘At a party.’

‘Obviously. Whose?’

‘None of your business.’

‘That,’ Jessel said mildly, ‘is for me to decide.’

Calder took off his coat and shapka. In the kitchen he dropped ice-cubes into a glass and poured Narzan mineral water onto them. The ice-cubes cracked back at him. The vodka had made his tongue thick and unmanageable.

Glass in hand, he went back to the living room. Jessel had lit his pipe and rearranged the chess pieces in pre-battle order.

Calder gestured around the room with “his glass. ‘Clean?’

Jessel picked up the bag containing his electronic sweep. ‘As a whistle. The comrades must trust you. What were you drinking, paint-remover?’

Jessel wasn’t a great drinker. He took care of himself and jogged every morning along the banks of the Moscow River. He was tougher than his appearance suggested.

Calder said: ‘You know better than that: they don’t trust anyone.’

He moved to the window and gazed at the floodlit public gardens below. He enjoyed them. In summer they dozed dustily; in winter they radiated vitality as youngsters with polished faces skated exuberantly along paths hosed with water to convert them into canals of ice.

In fact he enjoyed the apartment near the monumental buildings of Gorky Street, the best bakery in town and the extravagances of Gastronom No. 1. Compared with the barrack-block flats occupied by most of the defectors it was a palace and attracted much envious comment. But then they didn’t know what he knew. He was a VID, a Very Important Defector, and as such was entitled to a home isolated from the Brigade. He even had a wooden dacha in the country. Dalby was the only other defector with one of those.

Jessel said: ‘You’d better take white. In your condition you need the extra move.’

‘I can still beat you blind-folded,’ Calder told him. In fact there wasn’t much to choose between the two of them, although Jessel was the more cautious player, Calder finding it difficult to resist a potentially swashbuckling brilliancy without assessing it thoroughly. Patience was what he lacked. Jessel’s careful intricacies had earned him the right to play in a few minor tournaments in the Soviet Union and to spy in unlikely places. ‘I’ll take black,’ Calder said.

P-K4.

P-K4.

Calder made his move standing beside the marble-topped coffee table and continued to patrol the living room; movement, he hoped, would help to sober him up. The apartment helped to settle him – he had grown into it and it was shabby like himself. Period Muscovite with sombre furnishings and a rich, balding carpet; but it did contain small glories such as carvings leafed with gold, a painting of Siberian pastures feathered with mauve blossom, a chandelier whose frozen tears had been washed with soapy water only that morning by Lidiya, his maid. Unlike so many members of the Twilight Brigade he hadn’t cluttered it with bric-à-brac, the detritus of the abandoned West.

‘Your move,’ Jessel said.

‘Knight to queen’s bishop three,’ Calder replied without looking at the board.

‘You’re very sure of yourself.’ Jessel undid his button-down collar and loosened his striped tie.

‘How many times have we played the Ruy Lopez before?’

‘I might surprise you this time.’

‘Surprise me,’ Calder said.

A few minutes consideration, then: ‘Your move again.’

‘Pawn to queen’s rook three,’ Calder said, again without looking. The popular line these days, when vodka was your second and you had to play carefully.

Looking at the sparkling chandelier, he hoped he hadn’t been too abrupt with Lidiya earlier that day. She had been waiting for him when he had returned from the Institute, normally docile features animated. Apparently she had joined a queue in Warna, the Bulgarian store on Leninsky, and bought a cherry-coloured dress with a flared skirt. Despite the fact that five hundred other women would be wearing the same dress she was delighted with her purchase and she was wearing it for him.

He was touched. ‘Very pretty,’ he told her.

She smoothed the skirt against her thighs. She had been allotted to him when he first came to Moscow and she had served him well in the apartment, adequately in bed.

Respect had arisen between them although even now he didn’t really know if she enjoyed the love-making: it seemed to him to owe a lot to a Western sex manual given to her to cater for a decadent American’s appetites.

She was a lean woman with surprisingly large breasts. She was frankly plain and might one day look spinsterish, but there was a pleasing serenity about her and her brown hair curled prettily at the nape of her neck.

‘Would you like me to stay?’ she asked him but he told her no, he had work to do, and she departed ostensibly unperturbed, but you could never really tell with Lidiya.

The reason for the dismissal had been the invitation to the party from Katerina Ilyina.

Calder sat down at the coffee table and considered the Ruy Lopez developing on the board. He had little doubt that Jessel would move his bishop to rook four and that he would be able to produce a reasonable opening game by making copybook moves. By the ninth move they had progressed predictably to the Closed Defence. No dazzling variations tonight. Wasn’t it Reti who had said that a player’s chess style tended to be the opposite to his life-style? Tonight that made him a buccaneer off the board.

Calder moved his knight to queen’s rook four. The Chigorin System still as popular as ever nearly eighty years after the master’s death. When your own adventurous instincts were temporarily paralysed you could do worse than follow the father of the modern Soviet chess who had confounded the old Tarrasch school.

He said: ‘How’s Harry?’

Jessel said: ‘Whose party was it?’

‘A girl at the Institute.’

‘The new girl who looks after the files on the defectors?’

Calder nodded. ‘Harry?’

‘He’s fine. He’s got a sailboat and he’s hoping to take part in the Charles River Regatta in October.’

‘He isn’t sailing now, is he? It must be cold.’

‘It’s Boston,’ Jessel said. ‘He had a little accident the other day.’

Alarm spurted like acid. ‘How little?’

‘Very. He fell off his bicycle and grazed his knee.’

So why tell me? All part of the process, Calder assumed.

‘He’s still a Bruins freak of course,’ Jessel said, moving a bishop.

Still? Harry was only eight. ‘And Ruth?’

‘Where was the party?’

Calder gave him the address on Leningradsky.

‘Guests?’

‘Her mother and father were there.’

‘Step-father,’ Jessel corrected him. ‘Ruth’s finally passed all her exams and got a job teaching handicapped children.’

Who would have thought it? Ruth, one of the flowers of Bostonian society, arrogance her birthright. He saw her shopping in Newbury Street: the street seemed to belong to her.

Jessel said: ‘I presume this girl is stukachi.’

‘An informer? If she catalogues our lives she must be. One in twelve Soviet citizens are supposed to be KGB contacts, aren’t they? But I should think she’s innocent enough. You know, merely passing on updated material to her superiors.’

‘She’s into Women’s Lib isn’t she?’

‘You seem to know a lot about her.’

‘Sure, I do my homework.’

Calder knew that Jessel had contacts other than himself inside the Institute.

Jessel said: ‘Doesn’t that strike you as odd? You know, that a dissident of sorts should be employed there?’ He relit his pipe and blew smoke across the chess board; it smelled of autumn.

‘Ours not to reason why,’ Calder said.

Jessel stroked his long, sparse hair. ‘Aren’t you going to ask about your parents?’

Calder asked; he doubted whether they ever asked about him. His mother, perhaps.

‘Your mother’s fine. Your father had a stroke but he’s going to be okay. Maybe a little speech impediment.’

Calder found it difficult to imagine his father’s diction impaired. That magisterial voice saying grace before lunch – Calder had never quite forgiven God for semolina pudding.

‘How’s my mother taking it?’

‘Bravely. As always. It’s your move.’

Calder stayed with Chigorin. Pawn to bishop four.

Somewhere a clock chimed. He stood up and walked to the window. The floodlights had been switched off but he could see the bluish radiance of the street lights on Gorky Park. He closed the curtains.

Jessel was frowning at the board. What was bothering him about Calder’s play was his uncharacteristic conformity: it upset his own. Calder wondered how the party on Lenin-gradsky was progressing. For the first time he had been accepted by Russians, but only because his presence had been a lie.

Jessel said: ‘Is there still a lot of speculation about Kreiber?’

‘The rumours have become facts. He committed suicide, he was dumped beneath the ice after being knifed in his apartment, he was a double – or should it be triple – agent, a rapist, a homosexual ….’

‘He was a sad sack, ‘Jessel said, not quite touching his queen’s pawn. ‘So the Twilight Brigade is in disarray?’

‘Alarm bells have been sounded, sure. If Kreiber was murdered then the comrades were clumsier than usual. That blood on the edge of the ice ….’

‘And you, do you think he was killed?’

Calder shrugged. ‘It’s your move.’

‘Do you anticipate any more deaths? No one thinking of trying to get an exit visa?’

‘You must be kidding, ‘Calder said.

‘Not even figuratively? You know, retracing their footsteps.’

‘You think they’d tell me if they were? If they confided in anyone it would be Dalby.’

‘Alas, he’s not my pigeon.’ Jessel moved. P-Q4 as Calder knew he would.

Calder sat down and tried to concentrate but the firewater had frozen in his veins and his head was full of ice. He looked at Jessel who was examining his pipe the way pipe-smokers do, as if he had only just discovered it protruding from his mouth. ‘I quit,’ Calder said.

Jessel appeared mildly surprised; disconcerted never. ‘You really put one on, didn’t you?’ His speech was a curious mixture of slang and protocol English.

‘Do you mind if I go to bed?’