Полная версия:

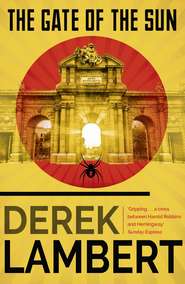

The Gate of the Sun

The Gate of the Sun

Derek Lambert

Copyright

Collins Crime Club

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

by Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1990

Copyright © Estate of Derek Lambert 1990

Cover Design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018 © HarperCollins Publishers 2018

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Derek Lambert asserts the moral right

to be identified at the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008287689

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008287696

Version: 2018-05-09

Dedication

For Jonathan, mi hijo

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

1975

Prologue

Part I: 1937–1939

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part II: 1940–1945

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part III: 1946–1950

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part IV: 1950–1960

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Part V: 1964–1975

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Keep Reading …

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

There must be an element of masochism in my nature because it would be intimidating enough for a Spaniard to write a novel about the labyrinth (Gerald Brenan’s apposite choice of word) that is Spain, let alone a foreigner. It may also be interpreted by Spaniards as an impudence. What possible pretext can an Englishman proffer for chronicling in fiction 40 years of Spanish history beginning with the outbreak of the Civil War in 1936? My only justification is that I wrote the book because I love Spain and its people, and I seek forgiveness for the mistakes and occasional liberties – the over-simplification in the Civil War of Fascist and Republican was perpetrated in the interests of clarity – that inevitably occur. I would like to believe, however, that I may have arranged the words in such a way that the vibrancy of Spain rises from the pages to obscure such infelicities.

PROLOGUE

Every morning the old woman in black packed a Bible in her worn bag, walked to church and prayed for forgiveness.

At first, newcomers drinking coffee and Cognac beneath the hams hanging in the Bar Paraiso questioned her fragile intensity but soon, like the old hands, they accepted her as part of the assembling day, as predictable as the arrival of Alberto, the one-legged vendor of lottery tickets and the screams of abuse from Angelica Perez as her husband scuttled from their apartment above the bakery.

None, unless they could cast their minds back 40 years, would have suspected that she had once set a torch to pews and vestments dragged from another church and spat upon a plump priest as he ran a gauntlet of hatred.

As for the woman she cared nothing for what they thought – scarcely heeded them, or the muted roar of traffic on the M30, or the squawk of the rag seller, as she made her way down a narrow street off the Marqués de Zafra in the east of Madrid.

She was 68 years old but she had spent her passions early and did not carry her years easily. Sometimes she mistook the boom and crackle of fireworks for gunfire, occasionally she confused the uniforms of the city police for the blue monos the militiamen once wore, but she did not dwell in the past. She lived rather in a suspended capsule in which the lengthening years and changing seasons were scarcely acknowledged.

Her hair was a lustrous white, combed tightly into a bun; her gaze, although the focus was remote, was steady; and her face had not yet assumed the fatalistic mask of the old and unwanted.

This bitter winter day she walked at her usual pace that never varied, whether the city was sweating in the heat of August or cowering before the snow-stinging winds of January. And such was the remote authority of her gait that the crowds parted before her as nimbly as pecking pigeons.

When she reached a corner lot, where children played basketball, the walls were daubed with fading graffiti and geraniums hung from pots crowding the balconies, she turned down an alley where, at the end, stood the church, its dome like a blue mushroom.

As she made her way down the street its occupants set their watches by her. A solicitor practising the scrolls of his signature, a purveyor of religious tracts scanning a mildly pornographic magazine, a greengrocer polishing fruit from the Canaries … At 9.18 she would enter the church, pray in the last-but-one pew and emerge at 9.23. What prayer she held in the chapel of her hands no one knew, only that it had been thus for 10 years or more.

But today she walked straight past the open door of the church without so much as a glance inside, causing consternation in this modest thoroughfare. What none of the inhabitants knew was that it was vengeance that had imparted that air of impartial arrogance for all those years and that today, instead of a Bible, she carried a gun in her worn bag.

CHAPTER 1

Difficult to believe on this February morning in 1937 that, as a new day was born in the sky, men on the earth below were dying.

Tom Canfield lowered his stubby little Polikarpov from the cloud to take a closer look, but all he could see were swamps of mist, broken here and there by crests of hills – like the backs of prehistoric monsters, he thought – and the occasional flash of exploding shells.

He nosed the monoplane with its camouflaged fuselage and purple, yellow and red tailplane even lower, as though he were landing on the mist over the Jarama river. Hilltops sped past, vapour slithered over the wings; he had no idea whether he was flying over Fascist or Republican lines, only that the Fascists were trying to cut the road to Valencia, the main supply route to Madrid, 20 miles north-west of the beleaguered capital and had to be stopped.

Three months ago he could not have told you where Valencia was.

Despairing of finding the enemy, he raised the snout of the Polikarpov, known to the Fascists as a rat, and flew freely in the acres between mist and cloud, a tall young man – length sharpened into angles by the confines of the cockpit – with careless fair hair that gave an impression of warmth, and the face of a seeker of truths. The mist was just beginning to thin when he spotted another aircraft sharing the space. He banked and flew towards it and as it grew larger and darker he identified it as an enemy Heinkel 51 biplane.

Enemy? I don’t know the pilot and he doesn’t know me. Why should we, strangers in a foreign land, try and shoot each other out of the wide sky? He adjusted his goggles which were in no need of adjustment and, with the ball of his thumb, touched the button controlling the little rat’s 7.62 mm machineguns.

Wings beat in the cage of his ribs.

He thought the German pilot of the Heinkel waved but he could not be sure. He waved back but he had no idea whether the German could see him.

His chest ached with the beat of the wings.

Tom learned to fly in the good days, in his father’s Cessna at Floyd Bennett Field, before his father was wiped out on Wall Street in the Crash of 1929.

Those were the days when, without pausing to spare good or bad fortune a thought, Tom had lived with his parents in a 32-roomed mansion at Southampton on Long Island, an apartment overlooking Central Park and a cabin at Jackman in Maine, near the Canadian border, where there was a lake stuffed with trout.

One day’s dealings on the Stock Exchange had erased these visible assets, and a lot more besides. Harry Canfield, self-made and bullishly proud of it, had suffered a stroke and his wife had mourned his convalescence with stoic martyrdom; the Cessna had been sold and Tom had quit Columbia Law School to earn a living.

Unprepared for routine labour, he had not prospered, succeeding only as a bouncer in a speakeasy until five Italians beat him senseless and concluding that period of his life share-cropping in Arkansas. By then he had lived in accommodation no bigger than a garden shed in a coal town in West Virginia and subsisted on soup made from potato peelings, and he had stood in a line in sub-zero temperatures in Minnesota waiting for a meal that had evaporated when he reached the head of the queue, and he had shared a brick-built shack in Central Park with commanding views of the blocks where the more fortunate citizens of New York still resided. And he had become rebelliously inclined.

When civil war broke out in Spain in July 1936, he and some 3,000 other Americans identified immediately and passionately with the Republicans – the workers, the peasants, the people – and crossed the Atlantic to help them fight their terrible, fratricidal battles. Some went through the Pyrenees, some reported to the recruiting centre of the International Brigades in Paris on the rue Lafayette.

Tom was interviewed in Paris by a chain-smoking Polish colonel with a shaven scalp and pointed ears who was reputed to have fought for the reds in the Russian civil war. He made notes in an exercise book with a squeaking pen in tiny mauve lettering.

What were Tom’s qualifications?

‘I can fly,’ Tom told him.

‘Aircraft?’ The colonel stared at him through the smoke rising from a yellow cigarette.

‘Boeings,’ Tom said.

‘Stearmans?’

‘P-26s,’ Tom lied because Stearmans were trainers and this shiny-scalped Pole with the exhausted eyes seemed to know his aircraft.

‘Age?’

‘Twenty-five.’

‘What’s the landing speed of a P-26?’

‘High, maybe 75 miles per hour.’

‘Politics?’

‘None.’

The colonel laid down his chewed pen. ‘Everyone has a political attitude whether they realize it or not.’

‘Okay, I’m for the people.’

‘An Anarchist?’

‘Sounds good,’ said Tom who had not thrown up on a cargo boat all the way from New York to Le Havre to be interrogated.

‘Communist?’

Tom shook his head and stared at the rain-wet street outside.

‘Socialist?’

‘If you say so.’

The colonel lit another cigarette, inhaling the smoke hungrily as though it were food. He scratched another entry in the exercise book. ‘Why do you want to fight in Spain?’

Tom pointed at a poster on the wall bearing the words SPAIN, THE GRAVE OF FASCISM.

‘Tell me, Comrade Canfield, are you anti-poverty or anti-riches?’

What sort of a question was that? He said: ‘I believe in justice.’

The colonel dipped his pen into the inkwell and wrote energetically. The rain made wandering rivulets on the window. Lenin smiled conspiratorially at Tom from a picture-frame on the wall.

‘You were born in New York?’

‘Boston,’ Tom said.

‘Why didn’t you go to Harvard?’

‘I went share-cropping instead.’

‘Please don’t play games with me. You see I, too, lived in New York. You’re no peasant, Mister Canfield, not with that accent.’

‘My father went bust.’

‘So why does the son of a capitalist want to fight for the Cause?’

‘Because bad luck is a two-edged sword, comrade. When we were rich I saw only the sea and the sky; when we went broke I saw the land and I saw people trying to make it work for them.’

‘And did it?’

‘I lived in a shack with a married couple with five kids in a coal town in West Virginia. Know what they paid them with?’

The colonel shook his head.

‘Coal,’ Tom said.

‘What were you paid in?’

‘Ideals,’ Tom said. ‘Do you have any objections to those, comrade?’ thinking: ‘Watch your tongue, or you’ll blow it.’

‘Why didn’t you join the Party?’

‘Which party?’

‘There is only one.’

‘You don’t reckon the Democrats or the Republicans?’

‘There’s not much to choose between them, is there? They’re all capitalists.’

‘What do you believe in, Colonel?’

‘In the class struggle. I believe that one day the slaves and not the slave-drivers will rule the world.’

‘Rule, Colonel?’

‘Co-exist. But please, I am supposed to be asking the questions. Do you believe in God?’

‘I guess so. Whether he’s Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish, or Catholic. Or Communist,’ he said.

‘The Fascists believe they have God on their side. Maybe you should fight for the Fascists.’

‘Perhaps I should at that.’

‘I’m afraid we can’t allow that.’ The colonel almost smiled and his pointed ears moved a little. ‘You see, we need pilots.’ He leaned forward and made a small, untidy entry in the exercise book.

At first Paris was a disappointment. The inhabitants of the arrondissement where he was staying resented penniless mercenaries on their streets and the other foreigners taking part in the crusade, particularly the Communists, were hostile to an American who, although he had picked fruit in California and collected duck shit at the east end of Long Island for fertilizer, still possessed the sheen of privilege. He was either slumming or spying.

When one Russian on his way to Spain as an adviser – they were all ‘advisers’, the Russians – accused him in a café of being a spy he resorted to his fists, a not infrequent expedient when his tongue failed him. The Russian, a Georgian with beautiful eyes and a belly like a sack of potatoes, fought well but he was no match for the middle-weight champion of Columbia.

‘So,’ the Russian said from between fist-thickened lips, ‘if you’re not a spy what the hell are you?’ He picked himself up from the wreckage of a table.

‘An idealist, I guess.’

‘With a punch like that?’ The Russian shook his head tentatively and touched one slitted eye. ‘Are you reporting to Albacete?’ Tom said he was. ‘Maybe I will become your commissar,’ continued the Russian. ‘I would like that.’ Followed by other advisers, he walked into the rain-swept street.

When the Russians had gone the sturdy bespectacled man in the corner said, ‘So you pack your ideals in your fists?’

Tom, who was beginning to think that ideals could get him into a lot of trouble, said, ‘He asked for it.’

‘And got it. Where did you learn to fight like that?’ His accent was Brooklyn, as refreshing as water from a sponge.

‘Columbia,’ Tom said, sitting at the table. ‘Where did you learn to talk like that?’

‘A rhetorical question?’

‘Rhetorical, Jesus!’

‘I come from Brooklyn and I mustn’t use long words?’ He beckoned a waiter. ‘Beer?’

‘Fine,’ Tom said, examining a bruised knuckle.

‘You a flier?’

‘Am I that obvious?’

‘I can see it in your eyes. Searching the skies. My name’s Seidler,’ stretching a hand across the table. His grip was unnecessarily strong; when people gripped his hand firmly and looked him straight in the eye Tom Canfield looked for reasons – he had become wise in the coal fields and the orchards.

The waiter placed two beers on the table.

‘Are you going to Spain?’ Tom asked doubtfully because with his spectacles and the roll of flesh under his chin Seidler did not have the bearing of a crusader.

‘To Albacete. Wherever the hell that is.’

‘Why?’ Tom asked.

‘Because Spain seems like a good place to fly.’

‘You’re a pilot? Wearing spectacles?’

‘For reading only.’

‘So why are you wearing them now?’

‘And for drinking beer,’ Seidler said.

‘Okay, stop putting me on. Why are you going to Spain?’

‘Isn’t it obvious? Me, a German Jew, Hitler and Mussolini, Fascists in Spain … Or am I addressing a punch-drunk college dropout?’

‘I used to collect duck shit,’ Tom said.

‘Guano,’ Seidler said. ‘Best goddamn fertilizer in the world.’ He took a deep draught from his glass. ‘So your old man went bust?’

‘How did you know that?’

‘Instinct,’ Seidler said tapping the side of his nose. ‘Who interviewed you? A Polak with pointed ears?’

‘He told you?’

‘Said you were a flier, too.’

‘A very stupid flier,’ Tom said. ‘Eyes searching the skies … Didn’t you have your eyes tested before you started flying?’

‘I’m short-sighted which means I can see long distances.’

‘So?’

‘I keep crashing,’ Seidler said.

After that Tom Canfield enjoyed Paris.

On 28 November Seidler and Canfield departed from the Gare d’Austerlitz on train number 77 on the first stage of their journey to the Spanish city of Albacete which lies on the edge of the plain, half-way between Madrid and the Mediterranean coast.

There were many volunteers on the train, French, British, Germans, Poles, Italians, and Russian advisers. Tom felt ill at ease with the leather-jacketed Russians: he had journeyed to Europe to fight injustice, not espouse Marx or Lenin or, God forbid, Stalin. But, as the train paused at small stations he was comforted by the crowds on the platforms waving banners, offering wine and, with clenched fists raised, chanting, ‘No pasarán!’ – they shall not pass. He was also cheered by the knowledge that he and Seidler were fliers, not foot soldiers; there is, as he was discovering, a pecking order in all things.

‘Tell me how you became a flier,’ he said to Seidler as the train nosed slowly past ploughed, wintry fields. Wine had spilled on his scuffed flying jacket, much shabbier than Seidler’s, and he felt a little drunk – happy to be here in Spain.

‘I wanted to join the Air Force,’ Seidler said, chewing grapes that a well-wisher had handed him and spitting the pips on the floor. ‘Actually volunteered, would you believe? I mean, do I look like Air Force material?’

‘It’s the spectacles,’ Tom said, but it was more.

‘They were polite. “Not quite what we’re looking for, Mr Seidler, but thank you for offering your services.” So I went back to selling books in a discount store on 42nd Street and learned to fly in New Jersey and waited for a war some place.’

Tom pointed at a miniature haystack on a church. ‘What the hell’s that?’

‘A stork’s nest,’ Seidler said. ‘Did you leave a girl behind?’

‘Nothing serious,’ Tom said.

‘Parents?’

‘My father had a stroke after he was cleared out. They live in a small hotel in upstate New York. They didn’t want me to come out here’ – the understatement of the year.

‘And you’re obviously an only child.’

Obviously? He remembered the house on Long Island and he remembered avenues of molten light on the water with yachts making their way down it, and men dressed in shorts and matelot jerseys drinking with his father, fierce moustache trimmed for his 60th birthday, and his mother dutifully reading to him in bed. She had been beautiful then, an older Katherine Hepburn, with chestnut hair piled high. He had never told them that he hated boats and, when he was lying on his back on the deck of the yacht, he was imagining himself at the controls of a yellow biplane exploring the castles of cloud on the horizon.

‘But you’re not,’ he said to Seidler.

‘Two brothers, one sister, all gainfully employed in the Garment Centre.’

The train which they had joined at Valencia stopped at a station, little more than a platform, and a dozen militiamen climbed on board. They wore blue overalls and boots, or rope-soled shoes, and berets or caps – one wore a French-style steel helmet, and two of them sported blood-stained bandages. Although the war had been in progress for only four months they conducted themselves like veterans and one carried a long-barrelled pistol which he laid carefully on his knees, as though it were made of glass. They were all young but they were no longer youthful.

Seidler spoke to them in Spanish. They were, he told Tom, returning to Madrid which had miraculously held out against the Fascist onslaught.

As Seidler talked and handed out Lucky Strikes, which were taken shyly and examined like foreign coins, Tom spread a map on his knees and tried to understand the war.

He knew that the Fascists, or Nationalists, were drawn from the army, the Falange and the Church, the landowners and the industrialists; that the Republicans were Socialists, trade unionists, intellectuals and the working class.

He knew that, to protect their privileges, the Fascists had risen in July 1936 to overthrow the lawful government of the Republic, established in 1931, which was being far too indulgent towards the poor. He had read somewhere that before the advent of the Republic a peasant had earned two or three pesetas a day.

He knew that the Fascists, led by General Francisco Franco, had, with the help of German transport planes, invaded Spain from North Africa and that in the north, led by General Emilio Mola, they had swept all before them. But great swathes of Spain, including the cities of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia, were still in the hands of the Republicans. No pasarán!