Полная версия:

The Sewing Circles of Herat: My Afghan Years

The Sewing Circles of Herat

MY AFGHAN YEARS

CHRISTINA LAMB

COPYRIGHT

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by Flamingo 2003

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2002

Copyright © Christina Lamb 2002

Christina Lamb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007142521

Ebook Edition © JULY 2012 ISBN: 9780007374083

Version: 2017-01-16

PRAISE

From the reviews:

‘Award-winning foreign correspondent Christina Lamb has written an inspiring and moving account of Afghanistan’s plight … Lamb shows that, despite attempts to destroy the country and its culture, its soul remains uncrushed.’

MARIANNE BRACE, Independent on Sunday

‘Deeply penetrating, informative and always engaging … Through the dispiriting events under which Afghanistan continues to be submerged, Lamb continually finds delightful people who have latched on to the fact that Faith is an ecclesiastical word for credulity, and offer some hope for the country’s future.’

CAL MCCRYSTAL, Financial Times

‘Lamb has a curiosity that demands she listen to anyone – warlord, reluctant torturer, Pakistani intelligence officer, family of the last man hanged … And beyond the door of the “Golden Needle Ladies’ Sewing Classes” in Herat, Lamb is awed by that cultured city’s resistance … which, as [she] understands, matters more than pages of guns and rubble.’

VERONICA HOWELL, Guardian

‘A remarkable blend of outrage, compassion and hope, Christina Lamb’s book is an alternately horrifying and uplifting insight into the Taliban regime.’

JUSTIN MAROZZI, Evening Standard

‘This book is in the best tradition of classics by British adventurers such as Robert Byron, Peter Levi and Eric Newby. In fact, Lamb’s empathy for the people she meets is such that her writing outdoes that of her stuffier male forebears. For Lamb, the country is more than just magnificent landscape and proud history. She has a long perspective from which to observe what she sees, having made a trip into Soviet-occupied Afghanistan at the end of the 1980s with a young Hamid Karzai, now the country’s dapper president … Her book boasts genuine journalistic exposés as well: she tracks down a Taliban torturer and discovers the Herat literary classes which, masquerading as sewing circles, concealed their activities from the religious police. After receiving a series of heartfelt letters about life in Kabul under the Taliban, she hunts for the young woman who wrote them.’

MARCUS WARREN, Daily Telegraph

DEDICATION

This book is dedicated to Lourenço

who thinks Mummy lives on a plane

and the fond memory of Abdul Haq who told me

‘You’re a girl. You can’t go to war in Afghanistan.’

EPIGRAPH

If you should ask me where I’ve been all this time I have to say ‘Things happen’.

PABLO NERUDA, No Hay Olvido, There’s No Forgetting

Peace is not sold anywhere in the world, Otherwise I would have bought it for my country.

GIRL IN AFGHANISTAN, ‘Lost Chances’ UNICEF Report, 2001

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

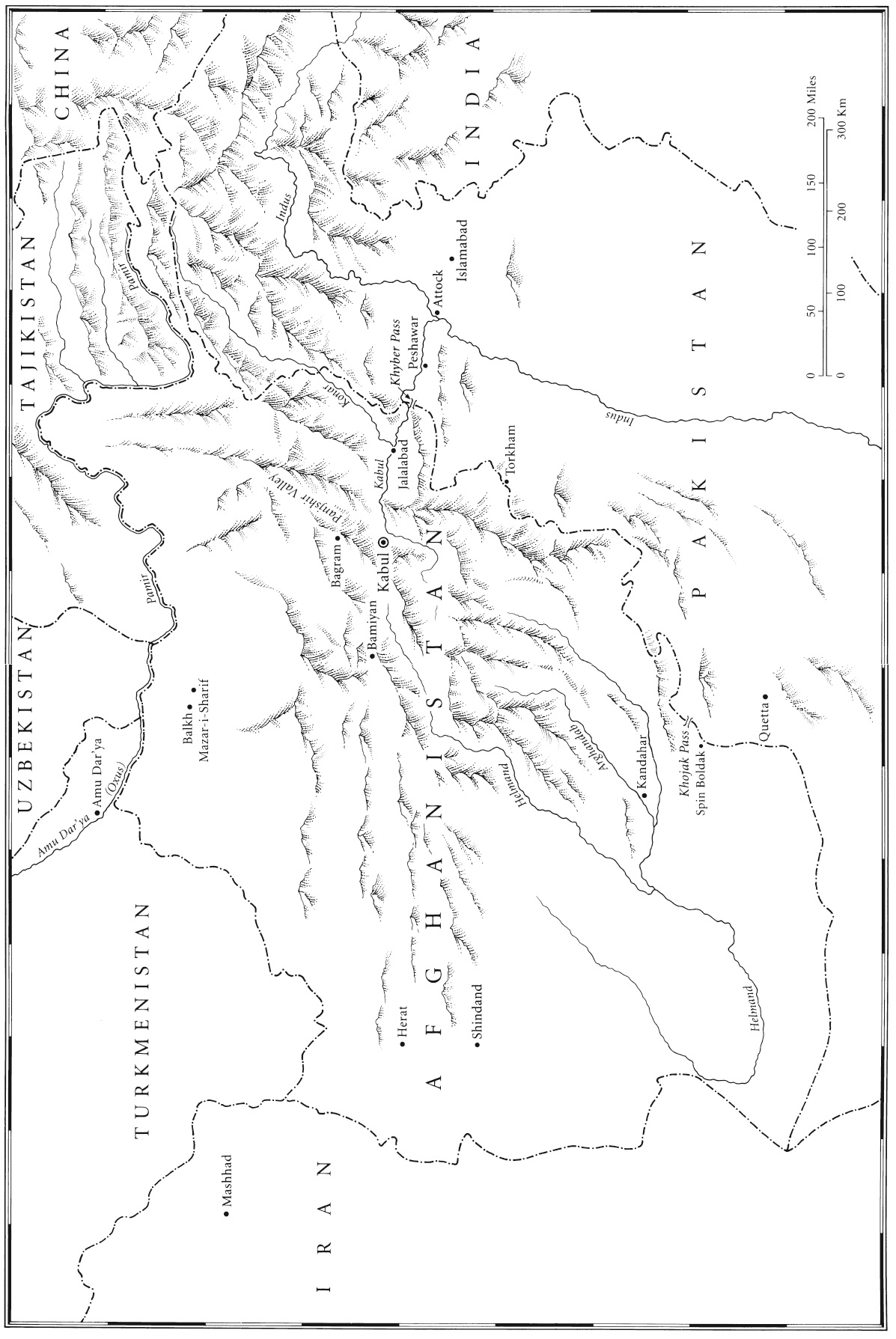

MAP

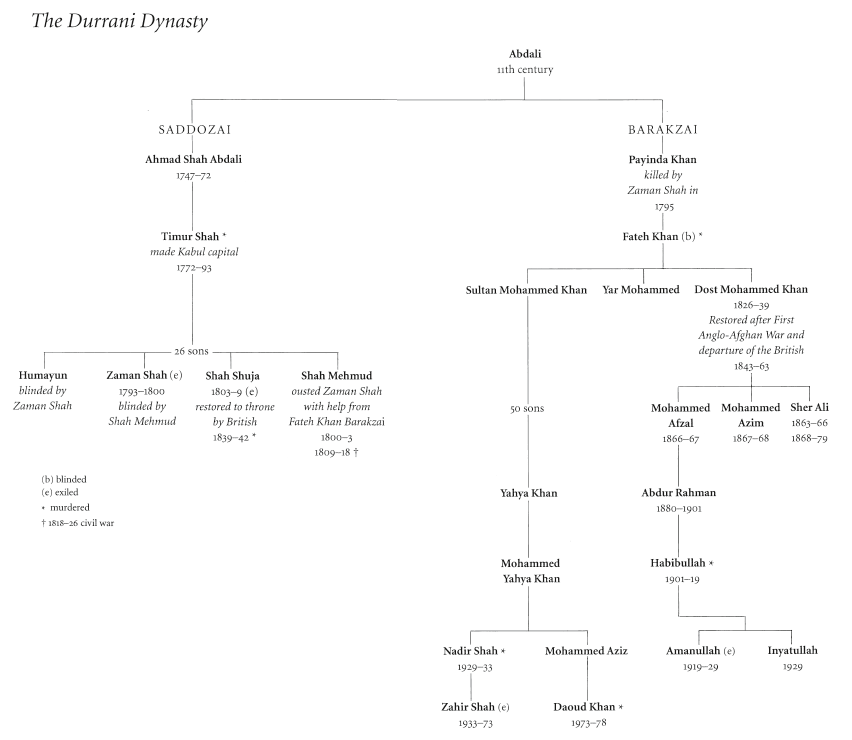

FAMILY TREE

Beginnings

The Taliban Torturer

Mullahs on Motorbikes

Inside the House of Knowledge

The Royal Court in Exile

The Sewing Circles of Herat

The Secret of Glass

Unpainting the Peacocks

The Story of Abdullah

Face to Face with the Taliban

A Letter from Kabul

KEEP READING

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Illustrations in the text:

Bird of Peace, from UNICEF report, 2001.

Mullah Khalil Ahmed Hassani, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Kandahar desert turned into battlefield, photographed by the author, 1988.

Hamid Karzai, 1988.

A child’s charcoal drawing.

The author on a Soviet tank, 1988.

Students in a madrassa.

Afghan training camp.

Motorcycling mullahs.

Abdul Wasei.

Ratmullah.

Eating mud crabs.

Ration book belonging to a dead soldier, Jelalabad 1989.

Sami-ul-Haq next to his garden wall, Islamabad 2001.

The Haqqania prospectus.

Sami-ul-Haq in Islamabad, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Princess Homaira © Julian Simmonds.

King Zahir Shah with President John F. Kennedy © Julian Simmonds.

King Habibullah © Julian Simmonds.

Letter to Bhoutros Bhoutros Gali.

King Zahir Shah and Queen Homaira in London, 1971 © Julian Simmonds.

Herat in ruins.

Ayubi, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Begging for nan, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Entrance to the Golden Needle, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Literary circle President Ahmed Said Haghighi in the classroom of the Golden Needle, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Zena and Leyla, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

The poet Khafash © Justin Sutcliffe.

Child’s drawing, from ‘Lost Chances’ UNICEF report on Afghanistan, 2001.

Egg game, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Cockfighting © Witold Krassowski/Network.

Afghan boys with missiles © PA News.

Sultan Hamidy’s business card.

Ismael Khan, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

‘Be a Second Marco Polo, Fly ARIANA’, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Ayubi’s letter to the author, 2001.

The author in Wasei’s convertible, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Cosmopolitan Kabul in the 1970s © Hulton Archive.

Dar-ul Aman © PA News.

Woman and child on the Dar-ul Aman.

Second Anglo-Afghan war © Hulton Archive.

The gardens of Paghman.

Buddhist sculpture, Kabul Museum before the Taliban © Topham Picturepoint.

Destroyed artefacts in Kabul Museum, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

President Hamid Karzai in Presidential Palace, Kabul, winter 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Washing blood off the Kandahar football stadium © Justin Sutcliffe.

Bor Jan.

The Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and the Prevention of Vice, 2001.

Guards in Mullah Omar’s house, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Mullah Omar’s fibre-glass fountain, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Bin Laden’s Eid Gah mosque, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Abdullah’s widow and children, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Nazzak, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Abdullah’s execution, 2001 © Corbis.

Hamid Gul, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

A make-shift fairground in Kabul, 2001.

Primary school text book, 2001 © Justin Sutcliffe.

Postcard greetings from Afghanistan, 2001.

Pir Mohammad, the letter writer, Kabul 2001.

Marri, 2001 © Steve Connors.

All pictures without credits are from the author’s personal collection.

MAP

FAMILY TREE

Beginnings

MY STORY like that of Afghanistan has no beginning and no end. The Pashtuns say that when Allah created the world he had a pile of rocks left over from which he made Afghanistan, and just as the historians seem unable to agree on when or how that far-off land of hills and mountains got its name, settling on the exact moment when it became part of my life seems an arbitrary process.

There is a dreamcatcher over my desk, a small cylinder made with loops of tiny seeds out of the bottom of which dangle four small bunches of turquoise, scarlet and yellow macaw feathers. Crafted by Indians who still live by the old ways in a remote river inlet of the Amazon, it is meant as its name suggests to catch dreams, filtering out the nightmares and only allowing through the good ones. As I begin to write in the pale light of dawn, I suddenly notice it moving, the feathers fluttering wildly even though there is no wind in my small study. I check the window and it is firmly closed yet the coloured feathers refuse to still.

On my desk is a handful of letters from a woman of about my own age in Kabul. She risked her life to get them to me and this is also her story. But if I must choose a moment to start my tale it would be when I was twenty-one years old, a graduate of philosophy at university and of adolescence in British suburbia, stumbling out of a battered mini-bus in the Old City of the frontier town of Peshawar, dizzy with Kipling and diesel fumes. Clenched in my hand was a suitcase I could barely lift, containing everything I imagined I would need for reporting a war, from packets of wine gums and a tape of Mahler’s Fifth to a much-loved stuffed pink rabbit, missing one ear.

If I close my eyes, I can conjure up the image of standing there, momentarily unsure in the dust-laden sunset, a gawky English girl, surrounded by motor rickshaws painted with F-16 fighter jets, beggars with missing arms or legs or faces eaten away by leprosy, and men in large turbans or rolled woollen caps selling everything from hair-grips to Shanghai White Elephant torches and wearing rifles as casually as Londoners carry umbrellas. The streets were ancient and narrow with two-storey wooden-framed buildings and across one hung a giant movie placard of a sultry raven-haired beauty drawing a crimson sari across cartoonish eyes. Everywhere such faces, carved with proud features as if from another time, some wise and white-bearded in sheepskin cloaks, others villainous with kohl-rimmed eyes. These were the Pashtuns of whom Sir Olaf Caroe, the last British Governor of the Frontier, had written ‘for the stranger who had eyes to see and ears to hear … here was a people who looked him in the face and made him feel he had come home’.

A rickshaw took me to Greens, a hotel mostly frequented by arms dealers, where I was given a room with no curtains. I lay on the thin mattress, looking northwest to a sky dark with a serrated mountain range. Beyond those dragon-scale peaks lay Soviet-occupied Afghanistan, the remotest place I had ever imagined suddenly only forty miles away.

If ever there was a country whose fate was determined by geography, it was the land of the Afghans. Never a colony, Afghanistan has always been a natural crossroads – the meeting place of the Middle East, Central Asia, the Indian Subcontinent and the Far East – and thus frequently the battlefield and graveyard of great powers. Afghans spoke of Marco Polo, Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, and Tamerlane as well as various Moghul, Sikh and Persian rulers as if they had just passed through.

The Red Army were the latest in a long line of invaders going back to the fourth century BC when Alexander the Great spent three years crossing the country with 30,000 men and elephants, taking the beautiful Roxanne as his wife en route. During the nineteenth century, the country’s vast deserts and towering mountains provided the stage for what became known as ‘The Great Game’, the shadowy struggle between the British Empire and Tsarist Russia for dominance in the region, in which many of the players were individual officers or spies, often as young as I was when I first stepped out of that Flying Coach.

Peshawar had once been part of Afghanistan, used by its kings as their summer capital, and that first night in Greens was the start of two years which turned everything I had known or valued upside down. Coming home again would never be the same.

Smuggled back and forth across the Khyber Pass in an assortment of guises and on a variety of transport with the mujaheddin, I found them brave men with noble faces who exuded masculinity yet loved to walk hand-in-hand with each other and pick flowers, or who would sit for hours in front of hand mirrors clipping their nostril hairs with nail scissors. They exaggerated terribly, never claiming to have shot down just one Soviet helicopter but always seven. Yet they were poetic souls such as Ayubi, one of Commander Ismael Khan’s key lieutenants in western Afghanistan and a huge bear of a man in a Russian fur hat who would silence a room by walking in, but who on bidding farewell, penned me a note in the exquisite loops and swirls of Persian script saying ‘if you don’t think of me in 1000 years I will think of you 1000 times in an hour’.

Crouching in trenches watching the nightly show of red and green tracer-fire light up the sky, breakfasting on salted pomegranate pips as rockets whistled overhead, I was supremely happy and alive. With the confidence of youth, I thought I was indestructible.

Part of the charm was the romance of being with people fighting for a cause after a childhood on the not exactly lawless borders of Surrey and south London where the local idea of rebellion was to go shoplifting in Marks & Sparks, and the biggest challenge finding a way home after missing the last train back from a concert at the Rainbow Theatre. Even at university, the only issues we could find to protest about were rent increases and the investments of Barclays Bank in South Africa’s apartheid regime. I had read Hemingway, got drunk and melancholic on daiquiris, and longed for a Spanish Civil War of my own.

But for me Afghanistan was more than that. It was about being among a people who had nothing but gave everything. It was a land where people learnt to smell the first snows or the mountain bear on the wind and for whom an hour spent staring at a beautiful flower was an hour gained rather than wasted. A land where elders rather than libraries were the true source of knowledge, and the family and the tribe meant far more than the sum of individuals.

When I returned to Thatcherite London where the streets were full of people rushing, their faces seeming to glitter with greed, Afghanistan felt like a guilty secret, my Afghan affair.

At a dinner party in north London, I listened to friends bragging about buying Porsches with their bonuses and sending out from their offices for pizzas and clean shirts because they were clinching a deal and could not leave their desks. I wanted to tell them of a place where every family had lost a son or a husband or had a leg blown off, almost every child seen someone die in a rocket attack and where a small boy had told me his dream was to have a brightly coloured ball. But, when I began to talk about Afghanistan, I watched eyes glaze and felt as if I was trying to have a conversation about a movie no one else had seen.

Over the next few years, I moved to South America then North, to South Africa then southern Europe, and found new stories, friends and places. Yet like an unfinished love affair, Afghanistan was always there. Every so often I got a call from people from those days and, to my shame, would see the message and not reply. Occasionally I saw a deep enamel blue that reminded me of the tiled mosque in Mazar-i-Sharif, ate an exquisite grape that reminded me of Kandahar where locals boasted they grew the sweetest in the world, or smelled a pine tree that brought back the horse-drawn tongas jingling along the avenues of Herat. My travels took me to remote parts of Africa and, lying under a star-sprinkled sky in northern Zambia, I suddenly remembered years before sleeping in the Safed Koh, the White Mountains near Jalalabad, silenced by the immensity of the heavens and a commander telling me that every star is a dead mujahid.

I returned to Pakistan whenever there was a change in government or military coup, which was often. The refugee camps into which a quarter of Afghanistan’s population had poured were bigger than ever and people talked of a sinister new group called the Taliban led by a mysterious one-eyed man.

My Afghan friends were still there, life passing them by. The dashing young guerrillas had turned into balding middle-aged men with potbellies and glasses, left adrift by the West’s abandonment of their cause. Increasingly contemptuous of Pakistan where they had to live but which they blamed for all Afghanistan’s woes, one old friend called Hamid Gilani told me with glee that an Italian restaurant called Luna Caprese had opened in Islamabad and suggested we dine there. When I arrived, there was an open can of Coca-Cola at my place. ‘It’s special Coke to drink a toast to the old days,’ he laughed. Lifting it to drink, I realised he had filled it with illicit red wine.

Behind Hamid’s glasses I could see crescents of tears rimming his eyes. ‘Seeing you cleans my heart’, he said. ‘You have a husband, a baby, a job and a home and I salute you. I am a man who has given his youth to the struggle for a place that no longer exists.’

Suddenly on September 11th all that changed as half a world away two planes smashed into the World Trade Center and another into the Pentagon. Danger had come out of a clear blue sky and nothing would be the same again. Watching the horribly compelling scene over and over on my television, holding my two-year-old son Lourenço who kept shouting ‘Mummy, plane crashing’, I listened to the pundits pontificate on who might be responsible. That the planes had been hijacked by suicide bombers immediately pointed to the Middle East. Saddam Hussein, Washington’s arch-enemy, was top of the list of suspects. But there was another name. That of Saudi-born terrorist Osama bin Laden. Not only had he repeatedly vowed war on the West, but, said one expert, he had even sent a message from his lair in Afghanistan to an Arab newspaper a few weeks earlier saying that he was planning a spectacular attack.

Afghanistan. It was as if a ghost had walked across my grave. As the map came up on the screen to show viewers the whereabouts of this forgotten country squashed between Iran, Pakistan, the – stans of central Asia and one thin arm just touching China, I instinctively clutched at my neck for the silver charm I used to wear on a chain. The charm was a map of a far-away country with the words Allah-o-Akbar, God is Great, etched across it in lapis lazuli, and it had been given to me years before by a tubby commander with a short beard and twinkling eyes called Abdul Haq with whom I once used to eat pink ice-cream.

Twelve years had passed since I had last breathed the air of Afghanistan. In that time large parts of its capital had been turned to rubble in fighting, tens of thousands more people killed, the regime of the one-eyed mullah had locked away its women, hanged people from lampposts, smashed televisions with tanks and silenced its music, and for the last few years even the rains had stopped. Would I still find the cobalt blue of the mosque in Mazar-i-Sharif where the white doves flew, the smell of pines on the hot Wind of One Hundred and Twenty Days in Herat, the same burst of sweetness on the tongue from the grapes of Kandahar?

On my desk next to my computer, the holiday faces of my husband and son smiled out trustingly from a snapshot in a yellow frame and in my drawer were thick files of invoices for mortgage and utility bills, nursery fees and guarantees for all manner of electrical appliances. Did I really want to return to that unforgiving land of rocks and mountains stained by the blood of so much killing, or a place inside me when I was young and fearless with all my life and dreams ahead of me? And if I did rediscover that person would I destroy everything I had? The dreamcatcher seemed to know.

1 The Taliban Torturer

‘The evil that men do lives after them, the good is oft interred with their bones.’

SHAKESPEARE, Julius Caesar

THE INSTRUCTIONS FROM the commanding officer were clear.

‘You must become so notorious for bad things that when you come into an area people will tremble in their sandals. Anyone can do beatings and starve people of food and water. I want your unit to find new ways of torture so terrible that the screams will frighten even crows from their nests, and if the person survives he will never again have a night’s sleep.’

I listened in horror. We were sitting at a table in the orchard of the Serena Hotel in Quetta in early October and the evenings were just starting to turn cold. There was a homely scent of apples from the trees all around and the sound of water trickling through narrow pebble-filled canals crisscrossing the orchard. Up above, the Milky Way cut a dusty path through a sky sprinkled with stars. I remembered long ago, on a chilly mountaintop in Paktia, a mujahid telling me that this was the trail left by the Prophet’s winged horse Buraq as he galloped towards the heavens.