скачать книгу бесплатно

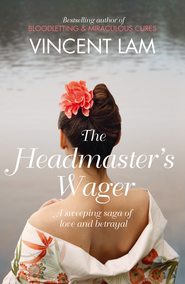

The Headmaster’s Wager

Vincent Lam

From internationally acclaimed and bestselling author Vincent Lam comes a superbly crafted, highly suspenseful, and deeply affecting novel set against the turmoil of the Vietnam War.Percival Chen is the headmaster of the most respected English school in Saigon. He is also a bon vivant, a compulsive gambler and an incorrigible womanizer. He is well accustomed to bribing a forever-changing list of government officials in order to maintain the elite status of the Chen Academy. He is fiercely proud of his Chinese heritage, and quick to spot the business opportunities rife in a divided country. He devotedly ignores all news of the fighting that swirls around him, choosing instead to read the faces of his opponents at high-stakes mahjong tables.But when his only son gets in trouble with the Vietnamese authorities, Percival faces the limits of his connections and wealth and is forced to send him away. In the loneliness that follows, Percival finds solace in Jacqueline, a beautiful woman of mixed French and Vietnamese heritage, and Laing Jai, a son born to them on the eve of the Tet offensive. Percival's new-found happiness is precarious, and as the complexities of war encroach further and further into his world, he must confront the tragedy of all he has refused to see.Blessed with intriguingly flawed characters moving through a richly drawn historical and physical landscape, The Headmaster's Wager is a riveting story of love, betrayal and sacrifice.

For William Lin

Contents

Cover (#u563fd600-e5ee-5ca8-a24b-32e5763847ac)

Title Page (#u4e9143fa-0278-53e5-9e84-cd99d905988c)

Dedication (#u11bb0398-04dc-535d-84d1-f5f8b4e2788e)

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part Two

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Part Three

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part Four

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgements

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Rocks stand stock-still, unawed by time and change.

Waters lie rippling, grieved at ebb and flow.

LADY THANH QUAN

(#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

CHAPTER 1 (#u87f8b66d-f83e-5ed2-ae43-7721f87c789d)

1930, Shantou, China

On a winter night shortly after the New Year festivities, Chen Kai sat on the edge of the family kang, the brick bed. He settled the blanket around his son.

“Gwai jai,” he said. Well-behaved boy. “Close your eyes.”

“Sit with me?” said Chen Pie Sou with a yawn. “You promised …”

“I will.” He would stay until the boy slept. A little more delay. Muy Fa had insisted that Chen Kai remain for the New Year celebration, never mind that the coins from their poor autumn’s harvest were almost gone. What few coins there were, after the landlord had taken his portion of the crop. Chen Kai had conceded that it would be bad luck to leave just before the holiday and agreed to stay a little longer. Now, a few feet away in their one-room home, Muy Fa scraped the tough skin of rice from the bottom of the pot for the next day’s porridge. Chen Kai smoothed his son’s hair. “If you are to grow big and strong, you must sleep.” Chen Pie Sou was as tall as his father’s waist. He was as big as any boy of his age, for his parents often accepted the knot of hunger in order to feed him.

“Why …” A hesitation, the choosing of words. “Why must I grow big and strong?” A fear in the tone, of his father’s absence.

“For your ma, and your ba.” Chen Kai tousled his son’s hair. “For China.”

Later that night, Chen Kai was to board a train. In the morning, he would arrive at the coast, locate a particular boat. A village connection, a cheap passage without a berth. Then, a week on the water to reach Cholon. This place in Indochina was just like China, he had heard, except with money to be made, from both the Annamese and their French rulers.

With his thick, tough fingers, Chen Kai fumbled to undo the charm that hung from his neck. He reached around his son’s neck as if to embrace him, carefully knotted the strong braid of pig gut. Chen Pie Sou searched his chest, and his hand recognized the family good luck charm, a small, rough lump of gold.

“Why does it have no design, ba?” said Chen Pie Sou. He was surprised to be given this valuable item. He knew the charm. He also knew the answers to his questions. “Why is it just a lump?”

“Your ancestor found it this way. He left it untouched rather than having it struck or moulded, to remind his descendants that one never knows the form wealth takes, or how luck arrives.”

“How did he find it?” Chen Pie Sou rubbed its blunted angles and soft contours with the tips of his fingers. It was the size of a small lotus seed. He pressed it into the soft place in his own throat. Nearby, his mother, Muy Fa, sighed with impatience. Chen Pie Sou liked to ask certain things, despite knowing the response.

“He pried it from the Gold Mountain in a faraway country. This was the first nugget. Much more was unearthed, in a spot everyone had abandoned. The luck of this wealth brought him home.”

It was cool against Chen Pie Sou’s skin. Now, his right hand gripped his father’s. “Where you are going, are there mountains of gold?”

“That is why I’m going.”

“Ba,” said Chen Pie Sou intently. He pulled at the charm. “Take this with you, so that its luck will keep you safe and bring you home.”

“I don’t need it. I’ve worn it for so long that the luck has worked its way into my skin. Close your eyes.”

“I’m not sleepy.”

“But in your dreams, you will come with me. To the Gold Mountain.”

Chen Kai added a heaping shovel of coal to the embers beneath the kang. Muy Fa, who always complained that her husband indulged their son, made a soft noise with her tongue.

“Don’t worry, dear wife. I will find so much money in Indochina that we will pile coal into the kang all night long,” boasted Chen Kai. “And we will throw out the burned rice in the bottom of that pot.”

“You will come back soon?” asked Chen Pie Sou, his eyes closed now.

Chen Kai squeezed his son’s shoulder. “Sometimes, you may think I am far away. Not so. Whenever you sleep, I am with you in your dreams.”

“But when will you return?”

“As soon as I have collected enough gold.”

“How much?”

“Enough … at the first moment I have enough to provide for you, and your mother, I will be on my way home.”

The boy seized his father’s hand in both of his. “Ba, I’m scared.”

“Of what?”

“That you won’t come back.”

“Shh … there is nothing to worry about. Your ancestor went to the Gold Mountain, and this lump around your neck proves that he came back. As soon as I have enough to provide for you, I will be back.”

As if startled, the boy opened his eyes wide and struggled with the nugget, anxious to get it off. “Father, take this with you. If you already have this gold, it will not take you as long to collect what you need.”

“Gwai jai,” said Chen Kai, and he calmed the boy’s hands with his own. “I will find so much that such a little bit would not delay me.”

“You will sit with me?”

“Until you are asleep. As I promised.” Chen Kai stroked his son’s head. “Then you will see me in your dreams.”

Chen Pie Sou tried to keep his eyelids from falling shut. They became heavy, and the kang was especially warm that night. When he woke into the cold, bright morning, his breath was like the clouds of a speeding train, wispy white—vanishing. His mother was making the breakfast porridge, her face tear-stained. His father was gone.

The boy yelled, “Ma! It’s my fault!”

She jumped. “What is it?”

“I’m sorry,” sobbed Chen Pie Sou. “I meant to stay awake. If I had, ba would still be here.”

1966, CHOLON, VIETNAM

It was a new morning towards the end of the dry season, early enough that the fleeting shade still graced the third-floor balcony of the Percival Chen English Academy. Chen Pie Sou, who was known to most as Headmaster Percival Chen, and his son, Dai Jai, sat at the small wicker breakfast table, looking out at La Place de la Libération. The market girls’ bright silk ao dais glistened. First light had begun to sweep across their bundles of cut vegetables for sale, the noodle sellers’ carts, the flame trees that shaded the sidewalks, and the flower sellers’ arrangements of blooms. Percival had just told Dai Jai that he wished to discuss a concerning matter, and now, as the morning drew itself out a little further, was allowing his son some time to anticipate what this might be.

Looking at his son was like examining himself at that age. At sixteen, Dai Jai had a man’s height, and, Percival assumed, certain desires. A boy’s impatience for their satisfaction was to be expected. Like Percival, Dai Jai had probing eyes, and full lips. Percival often thought it might be his lips which gave him such strong appetites, and wondered if it was the same for his son. Between Dai Jai’s eyebrows, and traced from his nose around the corners of his mouth, the beginnings of creases sometimes appeared. These so faint that no one but his father might notice, or recognize as the earliest outline of what would one day become a useful mask. Controlled, these lines would be a mask to show other men, hinting at insight regarding a delicate situation, implying an unspoken decision, or signifying nothing except to leave them guessing. Such creases were long since worn into the fabric of Percival’s face, but on Dai Jai they could still vanish—to show the smooth skin of a boy’s surprise. Now, they were slightly inflected, revealed Dai Jai’s worry over what his father might want to discuss, and concealed nothing from Percival. That was as it should be. Already, Percival regretted that he needed to reprimand his son, but in such a situation, it was the duty of a good father.

Chen Pie Sou addressed his son in their native Teochow dialect, “Son, you must not forget that you are Chinese,” and stared at him.

“Ba?”

He saw Dai Jai’s hands twitch, then settle. “You have been seen with a girl. Here. In my school.”

“There are … many girls here at your school, Father.” Dai Jai’s right hand went to his neck, fiddled with the gold chain, on which hung the family good luck charm.

“Annam nuy jai, hai um hai?” An Annamese girl, isn’t it? It was not entirely the boy’s fault. The local beauties were so easy with their smiles and favours. “At your age, emotions can be reckless.”

The balcony door swung open and Foong Jie, the head servant, appeared with her silver serving tray. She set one bowl of thin rice noodles before Percival. She placed another in front of Dai Jai. Percival nodded at the servant.

Each bowl of noodles was crowned by a rose of raw flesh, the thin petals of beef pink and ruffled. Foong Jie put down dishes of bean sprouts, of mint, purple basil leaves on the stem, hot peppers, and halved limes with which to dress the bowls. She arranged an urn of fragrant broth, chilled glasses, the coffee pot that rattled with ice cubes, and a dish of cut papayas and mangos. Percival did not move to touch the food, and so neither did his son, whose eyes were now cast down. The master looked to Foong Jie, tilted his head towards the door, and she slipped away.

Percival addressed his son in a concerned low voice. “Is this true? That you have become … fond of an Annamese?”

Dai Jai said, “You have always told me to tutor weaker students.” In that, thought Percival, was a hint of evasion, a boy deciding whether to lie.