скачать книгу бесплатно

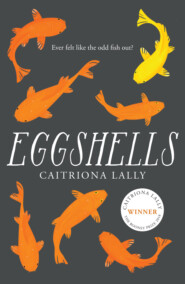

Eggshells

Caitriona Lally

WINNER OF THE ROONEY PRIZE 2018A modern Irish literary gem for anyone who has felt like the odd one out.‘Inventive, funny and, ultimately, moving’ GUARDIAN ‘Wildly funny’ THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW‘Beguiling’ THE IRISH TIMES‘Delightfully quirky’ THE IRISH INDEPENDENTVivian is an oddball.An unemployed orphan living in the house of her recently deceased great aunt in North Dublin, Vivian boldly goes through life doing things in her own peculiar way, whether that be eating blue food, cultivating ‘her smell’, wishing people happy Christmas in April, or putting an ad up for a friend called Penelope to check why it doesn’t rhyme with antelope. But behind her heroic charm and undeniable logic, something isn’t right. With each attempt to connect with a stranger or her estranged sister doomed to misunderstanding, someone should ask: is Vivian OK?A poignant and delightful story of belonging that plays with the myth of the Changeling and takes us by the hand through Dublin. A poetic call for us all to accept each other and find the Vivian within.

Copyright (#u13dc72c3-8b18-5605-b83b-0fdfea2f6a5c)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in 2015 by Liberties Press

Copyright © Caitriona Lally 2015

Cover design by Holly Macdonald © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover illustrations © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Book design by Fritz Metsch

Illustrations by Karen Vaughan

Caitriona Lally asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324407

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2018 ISBN: 9780008324414

Version: 2018-09-25

Praise for Eggshells: (#u13dc72c3-8b18-5605-b83b-0fdfea2f6a5c)

‘Inventive, funny and, ultimately, moving’

Guardian

‘Full of action and humour as its beguiling narrator takes her surreal jaunts around the capital in search of a portal to another world … The black comedy gives the book a jaunty quality that complements the dazzling trip around Dublin’

The Irish Times

‘Delightfully quirky … Vivian’s voice alone is enough to keep us reading, charmed by her unique brand of manic, word-hoarding wit’

Irish Independent

‘The book’s style calls to mind The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. Engaging and humorous’

The Dublin Inquirer

‘This urban fairy tale delivers something that is both subtle and profound in its examination of the human soul. Magically delicious’

Kirkus

‘Highly original, Lally has a unique voice as a writer’

Sunday Independent

‘A whimsical jaunt through Dublin and a modern take on many old Irish folktakes … Humorous, charming, and original’

Booklist

‘Eggshells expresses a Joycean sense of the ordinary. A brilliantly realised first-person narrative … a memorable debut’

Totally Dublin

‘Caitriona Lally has created a character of almost maddening originality’

Wales Arts Review

‘A highly impressive debut … a touching account of difference, showing how life must feel for somebody who cannot conform’

Books Ireland

Epigraph (#u13dc72c3-8b18-5605-b83b-0fdfea2f6a5c)

Sometimes the fairies fancy mortals, and carry them away into their own country, leaving instead some sickly fairy child … Most commonly they steal children. If you “over look a child,” that is look on it with envy, the fairies have it in their power. Many things can be done to find out if a child’s a changeling, but there is one infallible thing—lay it on the fire … Then if it be a changeling it will rush up the chimney with a cry …

—W. B. YEATS

Contents

Cover (#ufd6ac539-d5c8-53cd-b19c-36bdefda92b5)

Title Page (#u74e70933-ef02-539e-8fd3-6990a55fe1d2)

Copyright

Praise for Eggshells

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

About the Author

About the Publisher

1 (#u13dc72c3-8b18-5605-b83b-0fdfea2f6a5c)

WHEN I RETURN to my great-aunt’s house with her ashes, the air feels uncertain, as if it doesn’t know how to deal with me. My great-aunt died three weeks ago, but there is still a faint waft of her in every room—of lavender cologne mixed with soiled underthings. I close the front door and look around the house with fresh eyes, the eyes of a new owner. My great-aunt kept chairs the way some people keep cats. There are chairs in every room, in the hall, on the wide step at the bottom of the stairs and on the landing. The four chairs on the landing are lined up like chairs in a waiting room. I sometimes sit on one and imagine that I’m waiting for an appointment with the doctor, or confession with the priest. Then I nod to the chair beside me and say, “He’s in there a long time, must have an awful lot of diseases or sins, hah.” Some of the chairs are tatty and crusty, with springs poking through the fabric. Others are amputees. There are chairs in every colour and pattern and style and fabric—except leather, which my great-aunt said was the hide of the Devil himself. I go into the living room and sit in a brown armchair and examine the urn. It’s shaped like a coffin on a plinth—I chose it because death in a wooden box is more real than death in a jar. I shake it close to my ear, but I can’t hear a thing, not even a cindery whisper. I prise open the lid. The scratch of wood on wood is like a cackle through the ashes, the last laugh of a woman whose mouth never moved beyond a quarter-smile. I’ve seen people on television scattering ashes in significant places, but the only significant places in my great-aunt’s life were her chair and her bed, and if I scatter them there, I’d be sneezing Great-Aunt Maud for years to come.

I take the address book from the shelf and sift through it. There are a few A’s and C’s, a couple of G’s, an H and some M’s, but my great-aunt seems to have stopped making friends when she hit N. I take some envelopes out of the desk drawer and write the addresses on the envelopes: twenty-two in all. Twenty-six would be a symmetrical person-per-alphabet letter ratio, so I take the telephone directory from the shelf and flick through from the end of the alphabet. The pages are Bible-thin, and my fingers show up as ghostly grease-prints. I decide on Mr. Woodlock, Mrs. Xu, Mr. Yeomans and Miss Zacchaeus.

In school we sang about the tax collector who cheated people out of money. “Zacchaeus, Zacchaeus, Nobody liked Zacchaeus,” I sing, or I think I sing, but I don’t know what other ears can hear from my mouth. I open my laptop and type:

Hello,

You knew my Great-Aunt Maud. Here are some of her ashes.

Yours Sincerely,

Vivian

I print twenty-two copies of the letter, but it looks bare and mean, so I draw a pencil outline of the coffin-shaped urn in the blank space at the bottom. Now I type a different letter to the four strangers.

Hello,

You didn’t know my Great-Aunt Maud. You probably wouldn’t have liked her, unless you’re very tolerant or your ears are clogged with wax.

Yours Sincerely,

Vivian

I print four copies of this letter and fold all the letters into envelopes. I add a good pinch of ashes to each envelope and lick them all shut, my tongue tasting the bitter end of gluey. The pile of envelopes looks so smug and complete, I feel like I’m part of a grand business venture. Now I peer into the urn. The small heap of ashes, probably an elbow’s worth, looks like a tired old sandpit after the children have gone home for tea. I close the lid, put the urn on the bookshelf between two books, and sit down. I look around the room. The idea of owning something so unownable is strange: owning a house-sized quantity of air is like owning a patch of the sky. I laugh, but the sound is mean and tinny, so I take in a lung of air and laugh again—this one is bigger, but too baggy. I’ll save my laughs until I have worked on them in private. If anyone asks, I’ll tell them that I’m between laughs.

My glance keeps returning to the urn; I’m expecting the lid to open and the burnt eye of my great-aunt to peek out. When they were deciding how to bury her, I said she had always wanted to be cremated. It was a lie the size of a graveyard, but I wanted to make sure she was well and truly dead. I spot a thin slip of a book on the middle shelf and pull it out, wondering how a book could be made from so few words, but it’s a street map of Dublin, its edges bitten away by mice or silverfish. I unfold the map, spread it on a patch of carpet and write in my notebook the names of places that contain fairytales and magic and portals to another world, a world my parents believed I came from and tried to send me back to, a world they never found but I will:

“Scribblestown, Poppintree, Trimbleston, Dolphin’s Barn, Dispensary Lane, Middle Third, Duke Street, Lemon Street, Windmill Lane, Yellow Road, Dame Street, Pig’s Lane, Tucketts Lane, Copper Alley, Poddle Park, Stocking Lane, Weavers’ Square, Tranquility Grove, The Turrets, Cuckoo Lane, Thundercut Alley, Curved Street, The Thatch Road, Cow Parlour, Cowbooter Lane, Limekiln Lane, Lockkeepers Walk, Prince’s Street, Queen Street, Laundry Lane, Joy Street, Hope Avenue, Harmony Row, Fox’s Lane, Emerald Cottages, Swan’s Nest, Ferrymans Crossing, Bellmans Walk, The Belfry, Tranquility Grove, Misery Hill, Ravens’ Court, Obelisk Walk, Bird Avenue, All Hallows Lane, Arbutus Place.”

I close my eyes, circle my finger around the map and pick a point. When I open my eyes, I see that my finger has landed nearest to Thundercut Alley. If a thunderclap or lightning flash can transport characters in films and fairytales to other worlds, visiting Thundercut Alley might scoop me up and beam me off to where I belong, or cleave the ground in two and send me shooting down to another world. When my parents were alive, they tried to exchange me for their rightful daughter, but they must not have gone to the right places or asked the right questions. I crouch at the front door in the hallway and listen; I can’t hear my neighbours, so it’s safe to go out. I walk to the bus stop and stand beside a man wearing a grey jacket with a hood, holding a bottle of cola. He nods at me.

“Baltic, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

I give an exaggerated shiver, because one word seems a fairly meagre response. I think about the seas of the world.

“It’s really more Arctic than Baltic,” I say. “Surely the Arctic is the colder sea.”

“Yeah, yeah love.”

He unscrews the cap from the bottle, pours some on the ground in a brown hissing puddle and balances the open bottle on a wall. Then he takes a brown paper bag containing a rectangular glass bottle from inside his jacket, pours the clear liquid from the glass bottle into the cola bottle, and puts it back inside his jacket. When he takes a sup from the cola bottle, he smiles like he has solved the whole world.