Полная версия:

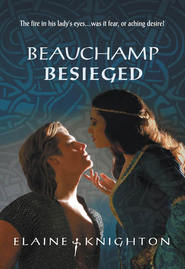

Beauchamp Besieged

“You are my husband.”

Raymond’s head snapped up, his face pale. He stood, then sat down again. “Nay…she is but—you cannot be—”

“Why not? ’Tis not the person that is important, but the pact. If I do not please you, that is regrettable, but be assured I find the prospect of wedding you no more appealing.”

“I did not expect you to find me appealing. I will force myself upon no one. Do as you will, go where you like.”

His defensive attitude surprised Ceridwen. Not knowing what to think, Ceridwen forged ahead. “Do I or do I not have your word that I may take up residence as your lady—in name only? You said you would not force—”

“I know what I said.” Raymond rose to his feet. “Once we are wed, I care not what you do. Just keep out of my way…!”

Beauchamp Besieged

Harlequin Historical #665

Harlequin Historicals is delighted to introduce new author ELAINE KNIGHTON

“Beauchamp Besieged is a triumph of a novel,

filled with the passion and pageantry of a bygone era,

heart-stirring romance and high adventure.”

—USA TODAY bestselling author Susan Wiggs

#663 TEXAS GOLD

Carolyn Davidson

#664 OF MEN AND ANGELS

Victoria Bylin

#666 THE BETRAYAL

Ruth Langan

Beauchamp Besieged

Elaine Knighton

Available from Harlequin Historicals and

ELAINE KNIGHTON

Beauchamp Besieged #665

I have many people to thank,

but I particularly need to acknowledge:

Linda Abajian, who believed from the beginning.

Shannon Caldwell, whose medieval expertise and

beautiful longbows inspired me.

Liz Engstrom, Wes Hoskins,

Deanna Mather Larson and Doe Tabor,

who taught me all about writing and to never give up.

Teresa Basinski-Eckford, Gwyn Cready, Sue Greenlee,

Sharon Lanergan, Evalyn Lemon, Laurel O’Donnell,

Ann Simas, Outreach International Romance Writers,

Rose City Romance Writers and many other members

of Romance Writers of America who

offered me unfailing advice and support.

My agents, Ron and Mary Lee Laitsch,

and my editors, Tracy Farrell and Jessica Regante,

who gave this story a chance.

And James Pearson, who told me so…

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Prologue

The Marches of England and southern Wales, 1180

“Slow down—I must lead!”

Raymond de Beauchamp ignored his brother Alonso’s snarling command. As of today he was a full ten winters old. As of today he was one year closer to being a man—a true warrior. And even Alonso could not prevent that.

He galloped his stout cob through the forest, heedless of Everard the Fat’s cries of distress at the pace. On a Welsh pony, little Percy bounced along behind, willing to follow anywhere if his three elder brothers let him.

Raymond gloried in the crisp air against his face. Golden leaves swirled and tumbled in the wake of the ponies’ hooves. Ahead was an open hill, with crags of rotten stone that broke apart as they trod upon them. At the top lay the dolmen. A forbidden place, where evil spirits lurked and wicked lads might forever disappear. At least that was what old Nurse Alys said.

The stone slab seemed impossibly large and heavy. Raymond halted and stared, caught up in its mystery, in its implications of age-old, sacred blood.

Alonso strutted its length, a lock of gilded hair falling over his eyes. He challenged the two youngest boys with his gaze. Blue, gleaming, sharp as a blade. “Raymond and Percy! Let us make an offering, like the old ones, upon this stone.”

Raymond stilled. So this was the price for winning the race through the forest. Everard, a chubby version of his older brother, stood next to his pony, twisting the reins around his hands. “Nay, ’twould be blasphemous to do such a thing.”

Alonso narrowed his eyes at Everard. “Did I ask you, knot-head? It will not be if I say it is not. Percy. You will do, for you are the sweetest and the softest. The crones who come here to dance this eve will feast upon you with delight.”

Grinning, he swung the child onto the slab.

The rosebud color drained from Percy’s cheeks. Raymond’s stomach tightened into knots of outrage. Percy was but a wee lad. Why, he still had creases of baby fat where his hands met his wrists. Loathing for Alonso filled Raymond, but he held himself in check, fiddling his sore, loose milk-tooth with his tongue. “Put him down, Alonso. He thinks you mean it.”

Alonso merely bared his teeth and continued preparing to tie Percy up. Raymond clenched his jaw despite the ache. His brother’s familiar, leering grin marred a face so fair that to all who did not know him, Alonso was surely a young man of nobility and honorable intent. But he had the heart of a carrion-eater, Raymond knew full well.

His blood pounded in a red wash of fury. He rammed his elder brother with his shoulder, fists pounding ribs. Alonso, taller, heavier, and more experienced, kneed Raymond in the belly, kicked his head, then dragged him upright by his hair.

“Never interfere with my pleasure, fool.”

Staring into ice-blue eyes, Raymond struggled to draw breath and longed to batter that sneering face. But Percy needed him, he must hold back. The child sat on the stone, his straw-colored hair awry, rubbing his eyes with dimpled hands.

Alonso unsheathed his dagger. “Well then. Someone has got to be it. If not Percy, then who?” He cut a length of rope and started to wind it around Percy’s wrists.

The lad turned a frightened gaze upon Raymond, who found it impossible to wink or smile in reassurance. He cleared his throat. “You desire a sacrifice? Let it be me.”

Alonso smiled. “’Tis always more pleasing to the gods when the victim is willing. Get off of there, Percy.”

The child stayed put, his lower lip trembling. “Nay. I will not let Raymie die for me.”

Alonso simply tossed Percy to the ground. The boy scrambled up and ran weeping to Raymond, who brushed the gravel from his small palms. “Hush! I am not going to die.” Raymond heaved himself onto the stone and hoped he’d spoken the truth.

“On your knees, Brother. We must do this properly.”

Raymond’s insides twisted as the cords bit into his wrists. “My hands are going numb.”

“Get used to it.” Alonso pulled harder.

Raymond began to struggle in earnest as his brother drew the bindings from his ankles around each thigh. Raw panic chewed at the last threads of his confidence, and sweat dampened his brow. “Alonso. I will not be hamfasted.”

“You already are. Everard, help me get this knot right.”

“Perhaps this is excessive.” Everard’s statement was more whine than protest.

Alonso jerked Raymond’s feet and hands together for the final stage of his bondage. “Everard, hamfasting is an art. Do it properly—you are going to be a churchman, are you not? So, you must know how to persuade your flock to confess!”

Everard pushed Raymond’s face against the stone slab. Now his wrists were behind him, lashed to his ankles. His heels were tight against his buttocks, and each ankle was bound to its respective thigh. The worst sort of criminals were hamfasted like this, before they were…Raymond fought down the terror welling within him. He would rather die than let them see it.

“Hurry up and be done, you swine!” He thrust his tongue into the painful socket of his tooth, which refused to let go.

“But, Brother, you are not in the true spirit of things.” Alonso’s eyes glittered in the lowering rays of the sun, and a new thought occurred to Raymond. Demons. It was the only explanation for Alonso’s extraordinary cruelty. Something evil must have slithered out of these woods and possessed him.

The shadows of the forest edge grew and touched the rim of the stone, even as ravens spiraled in to roost among the half-clad tree branches. The western sky glowed pink, but in the east lightning already flickered amidst rumbling, blue-black clouds. Night would bring new horrors to this place.

“Now, for the shedding of blood.” Alonso picked up his dagger and sighted down it, testing the edges with his thumb.

“You’ll be sorry you started this. I will come after you.” Raymond’s words belied the churning in his stomach. The rough stone scraped his cheek as Alonso rolled him onto his back, and his thigh muscles stretched to the point of pain. The skin of his throat was exposed to the cooling air.

Alonso breathed against Raymond’s cheek. “Father has not yet succeeded in drawing a single tear from your eyes, but mark me, it will come to pass. I have sworn to break you.” He straightened and laid his knifepoint at the soft hollow beneath Raymond’s jaw. “For what do we make this sacrifice, Brothers? Success in battle? Infidel’s gold? The power of kings? Or the guaranteed salvation of our souls, so we never have to sit through one of Father Brenner’s stupid catechisms again?”

Raymond’s heart thundered. The dagger-tip trembled against his skin, a deadly point of heat. Alonso hissed, “Perhaps to be rid of a damned sight of trouble in future?”

“Finish it, then,” Raymond growled.

“Nay!” Percy darted up and grabbed Alonso’s elbow.

The older boy jerked free of the little one’s grasp. The blade slipped into Raymond’s throat. Percy screamed.

Raymond swallowed his tooth. He gasped and howled out his rage until he choked, his mouth full of metallic-tasting blood. Seeping warmth coursed around his neck. Alonso’s gaze grew soft and liquid, as though he was charmed by the picture before him.

“We will leave him thus. ’Tis too perfect.”

Raymond burned, a hot, malevolent pool of hatred swirling within him. Percy’s cries grew into thin shrieks—high, piercing animal sounds that would not stop. Alonso wrapped one hand about his neck until the child was silent but for a few gurgling sobs. “Let us away.”

Hooves clattered against the rocky ground, then a shroud of silence settled upon Raymond. At first he could not believe his brothers had truly left him behind. But the twilight crept closer, winding chill, blue-gray fingers about the dolmen.

The darkening sky wheeled overhead, faster and faster, until nothing existed but his unvoiced scream. Soon the wolves would come, and he would die. Alone. An offering, a human sacrifice, meant to stay the heavenly wrath Alonso was surely accumulating.

Then, unbidden, like a gift from some ancient spirit of the dolmen, a cold blade of resolve cut through Raymond’s anguish. A new hardness permeated his heart, as if it were a piece of red-hot iron plunged into water. He welcomed the numbing calm, embraced its deadly resolution.

I will live. And one day, Alonso will not.

Chapter One

1196, sixteen years later, along the Marches

Already the battlefield reeked. Sir Raymond de Beauchamp wheeled his warhorse and arced his sword in a whistling blur of Spanish steel. The blade bit true and deep. He sucked in a great gulp of the stifling air within his helm, and watched the young Welshman topple from his small horse. The lordling died quietly, his blood streaming in bright contrast onto the spring verdure.

A hollow stab of regret pierced Raymond’s soul. The fellow had fought well. But, there was no time to reflect upon the valor of one already dead. Raymond surveyed the chaos around him. His knights galloped in a disordered frenzy over the field, attempting to hack their way through the steadfast Welsh.

Inwardly he groaned. As ever, the horsemen allowed their courage to outstrip their discipline, and for that they could lose the fight. Too many of the rebel Welsh were still in the safety of the forest beyond, firing deadly volleys from their formidable longbows. The dreadful hissing made Raymond’s gut clench even as he tried to calm his nervous horse. Neither his own mail, nor that covering the stallion would even begin to stop the penetration of a shaft loosed from one of those deceptively simple-looking weapons.

Raymond turned his head sharply at a sudden movement along the field’s edge. What he had taken to be a lifeless body jumped up and ran to the warrior he had just sent heavenward. A lad, barely old enough to be a squire, cradled the dead man’s head and wailed his grief. Raymond’s heart twisted in pity, despite his practiced detachment. So much blood, so many tears. The pitched energy he had summoned for the battle dissipated into a numbing weariness that spread through his limbs.

Hoofbeats thundered across the chopped turf of the meadow. It was his lieutenant, Giles. The boy would be cut to pieces and joining his master in a matter of moments. “Hold, Giles!” His friend could not hear him above the cries of fighting men and the keening of the lad. Raymond urged his mount forward and cut in front of Giles’s horse at a run.

The boy stared openmouthed as the galloping chargers bore down upon him. Raymond leaned low and grabbed the scruff of the lad’s tunic, throwing him across his horse’s neck. He swerved to avoid trampling the slain Welshman and nearly collided with Giles’s stallion. Even as Raymond improved his grip on the shrieking boy, a piercing, red-hot pain struck him. His prized destrier emitted a huffing groan and bolted, veering sideways. It took all his strength and skill to control the animal without letting go of the child, especially since he could not move his left leg. Searing torment flourished and spread with every movement. He clenched his jaw and broke into a sweat.

Then he looked down. An arrow had penetrated his thigh, his saddle, and mayhap even his horse. “Jesu—nay…” Raymond’s voice faded as the sharp agony wormed deeper. He fought to hold onto his struggling burden as they cantered toward safety. Giles already pounded away in useless pursuit of the hidden archer, a blood-curdling roar echoing after him.

A fresh assault began, this time to Raymond’s right leg. The boy, hanging upside down over the shoulder of the horse, swung his arm rhythmically with each stride of the animal, stabbing at his rescuer with a small dagger.

Raymond brought his knee up and gave the lad’s head a solid knock. The jabbing ceased. Pulling his horse to a rough halt in the shelter of a hillock, he threw the boy to the ground. The ungrateful whelp landed hard, gasping for breath.

Raymond tried to slow the wild thudding of his heart. He relaxed methodically to combat the pain, and spoke softly to his trembling, sweating mount. It would be an ordeal worthy of an inquisitor to get free of the arrow. All because he had succumbed to pity. Always a mistake.

The boy began to push himself up from the ground.

“Halt.” The curt order froze the lad, and Raymond stared.

Smooth cheeks beneath the mud, blood and tears. Long-lashed green eyes. A trembling body within a suspiciously full upper tunic. Holy Mary, if this was a boy, then he himself was a silkie from the sea. The horse took a deep breath and snorted. Raymond gritted his teeth against the jolt of fire that shot from hip to knee. “Take off that hood, damn you.”

Tangles of wavy black hair spilled down about a charming, oval face. Raymond caught his breath. He was right. A girl, typically Welsh, and heart stopping in her fragile beauty. Except for the loathing that seethed from her eyes. He was used to hate-filled stares from his enemies, but this chit could not be more than fifteen years of age, the same as Meribel, his own beloved lady-wife.

The thought of a young woman on a battlefield fanned his anger as well as his longing to be away from this outlandish place. Welsh women were famous for the atrocious battle-harvests they reaped from fallen enemies. His leg throbbed as his destrier pawed at the soft earth.

“Idiot wench, what were you about? Be glad I do not beat you for my trouble.” He forgot not to move in his saddle, and ground his teeth as the pain surged. A steady patter dripped from the underside of his stirrup.

“Just you try! Lord Talyessin’s archer has pinned you to your horse quite perfectly,” she said, grim triumph in her voice. “As you well deserve. I hope you die. Slowly.”

Pretending to ignore her, he scanned the battlefield. The girl scrambled to her feet, her weapon still in her raised fist. Raymond turned his horse and a nudge of the destrier’s shoulder knocked her flat once again. His mount shivered beneath him, and pain assailed his leg with unrelenting ferocity. Hot fury leaped in his chest at the maid’s audacity. A girl-child gone to war. Hell and damnation.

Perhaps his lord-brother Alonso was right. These people were mad. Bereft of reason. He shook his head at the sight of the girl, sprawled in the grass, one delicate hand clutching her knife as though it were a talisman against him and his kind.

Her eyes filled with tears. “You misbegotten Norman bastard! You’ve killed Owain. Murderer!”

Raymond regarded her in silence. Sympathy crept up on his pain and anger, but he swallowed the will-sapping emotion. He had already suffered a crippling wound on her behalf. “I am a misbegotten English bastard,” he growled. “And I would be your ally if your prince had any sense. Your friend Owain need not have died if you Welsh had the wits to capitulate.” With an effort, Raymond softened his voice. “Let us go home. You to yours, and I to mine. Do you understand, Cymraes?”

The girl stared, apparently startled at his use of her language. Welshwoman. Perhaps he had mispronounced it. The little witch need not glare at him like that. Raymond bit his lip to stifle the moan that threatened as his restless horse shifted. Black spots floated before his eyes.

“I do, Sais,” she said quietly. “And you understand this: I shall come for you one day, when you least expect it.”

Raymond felt the blood rise in his neck and was grateful for the helm that hid his face. Sais. Saxon. Anyone the Welsh considered beneath contempt, they designated as Sais. Coming from a Welsh mouth the word was synonymous with “pagan brute.” She could have offered no worse insult. “So you will come for me. How do you plan to find me? Do you know who I am?”

The girl raised her small chin defiantly. “It makes no difference—you are all the same. Filthy, two-faced marauders who bleed our borders in the name of the English king. I will find you. I will follow the carrion crows to your lord’s keep.”

Raymond’s helm muffled his humorless laugh. It was absurd to argue with this creature while he bled to death. “Bon chance to you then, my lady.” He looked up as Giles crested the hill. The big knight’s horse bounced to a stiff-legged stop before them, and Raymond blinked hard as his own destrier jigged.

“My lord, ’tis over. Talyessin’s men are slinking back to their holes. Come away from this vermin and let me see to your wounds.” Giles glanced briefly at the figure on the ground, then his steel-encased head swiveled back. “Merde, a lass? A bit bold for a camp-follower, methinks!”

“Meet my newest enemy, Giles. Sworn to see my bitter demise. Make certain she returns safely to her people. Oh, and find that pig-sticker she is hiding beneath her tunic. I would do it myself, but I am somewhat indisposed at the moment.” Without a backward glance, Raymond turned his horse and rode away.

Chapter Two

1200, four years later, southern Wales

Ceridwen paced before her father. Plain rushes crunched beneath her feet, not fine herbs or lavender. Lord Morgan’s hall at Llyn y Gareg Wen remained free of luxury. Firelight leaped on the stone walls, reflecting the gleam of lances, swords, and longbows, hung ready for retrieval at a moment’s notice.

“Nay, Da, I will not be your bait. God intervened when I was but a lass to spare me marriage to a Beauchamp. Now you wish again to make alliance with those soulless wolves?”

Morgan gently set his goblet on the scarred oak table. That he did not bang it down warned Ceridwen just how angry he was. “Be quiet and sit, child.” He turned his dark, sharp gaze full upon her. “For once you will do as you are told. You have disobeyed me in many things, but this shall not be one of them.” His leather-bottomed chair creaked as he rose and took over the pacing where she left off.

Ceridwen flung herself onto a seat opposite her elder brother, Rhys. Her half-dozen siblings watched with great interest, from nearly every available perch in the hall. Little Dafydd climbed into her lap. She stroked his dark hair and held him close. The wee ones needed her more than ever now that Mam was gone. She gulped back the lump in her throat and tried to concentrate on what her father was saying.

Morgan paused before the hearth and stared into the flames. “Old baron Beauchamp was wise to offer us peace once, through his youngest son, Parsifal. And as you say, Parsifal’s death was the result of intervention, divine or otherwise. But the remaining Beauchamp sons no longer have the counsel of their father. They harry us without mercy, and I cannot keep up this resistance forever.”

“But—”

Her father silenced her with a severe look. “The next eldest Beauchamp, Raymond, has a few more brains in his head than the others. That aside, he is land-hungry. He had to sell his late wife’s domains to fund the defense of his keep at Rookhaven. He chafes against the yoke his lord brother Alonso has placed round his neck.”

“And you wish me to act as the balm to soothe him?”

“I do!” Morgan’s fierce tone punctured her show of bravery. “Baron Alonso wields a vast fist of power. And Sir Raymond is the well-honed dagger within that fist. Alonso suspects Raymond is near the breaking point. He has promised me, if I do not find a way to thwart Raymond’s revolt, I, and all who are dear to me will suffer for it. And Alonso is a master of understatement.”

Her father smiled in a way that sent chills down Ceridwen’s spine. She hugged Daffyd until he squirmed out of her arms. Morgan’s gaze followed his youngest child’s search for a more comfortable female lap, then he continued. “What Alonso does not know is that I will control his brother by making an alliance with him. Alonso will be held at bay by the threat of both Raymond and the Talyessin, and we will have Raymond under our watchful eye. Your eye.” Morgan took his seat once again.

“What if I cannot bear the sight of this man, nor the uncouth sound of his language, nor his rabid touch? What would you have me do, when Owain’s blood is still unavenged?” Her handsome, fey Owain, both warrior and soothsayer. Ceridwen balled her hands into fists, digging her nails into her palms.

She remembered the day of his death with agonizing clarity. Owain had lain in the meadow as if asleep, but there was so much blood—she could still see the evil gleam from the eyes of the killer, within his shadowed helm. A knight under the Beauchamp banner had called her Cymraes, as though he thought her worthless and crude. And now she was being told to marry one of the monsters! Everyone knew what the English were like. They roasted their enemies over slow fires and ate them alive.