Полная версия:

The Lost Puzzler

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Eyal Kless 2019

Cover illustrations by Tithi Luadthong © Shutterstock.com

Cover design by Dominic Forbes © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

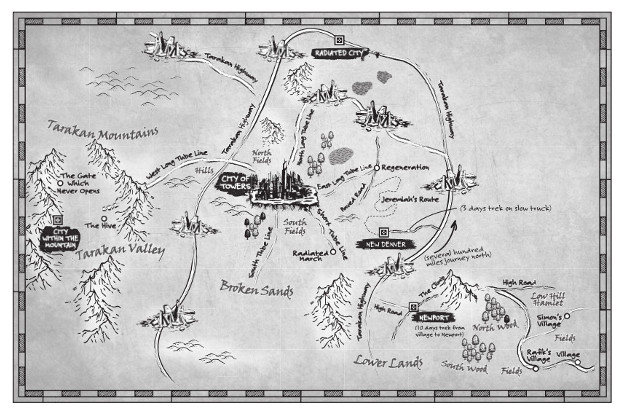

Map by Eric Gunther / Springer Cartographic LLC

Eyal Kless asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008272302

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008272319

Version: 2018-11-28

Dedication

To my loving parents,

Anat and Yair

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Map

1

Officially, the City of Towers was not divided. Modernity and progress, law and order reigned supreme. That is, if you believed the Council’s manifesto. Yet my cart driver didn’t seem to believe the official line and stopped his horses at the gate leading to the lower spires that most of the city dwellers called the Pit.

The cart’s driver bent down until his face was showing at the door’s open window.

“That’s as far as I go,” he grumbled.

“But this is not—” I began to protest.

“It’s as far as I go,” he repeated, as if this was the only explanation needed before his face disappeared. He did not even bother to jump down and open the cart’s door. That’s city cart drivers for you …

I should have argued with him—I’d paid hard metal in advance for the ride down all the way to the Pit—but I decided not to bother. I told myself that I was too tired to waste time and energy on a few coins, but in my heart, I knew that after months of traveling, it was a blessed change to have found anyone willing to take me, even for the shortest of distances. Only a few days’ travel from the city, most cart drivers took one look at my face and sped away. Some spat on the ground as they passed, while others, more often than I care to recall, aimed their spittle at me.

I climbed out of the filthy cart, holding the hem of my black coat in my free hand. The driver drove off without uttering a word, rightly assuming that no tip would be coming his way.

I carefully adjusted my cowl as I surveyed the enormous square of the city’s Central Plateau, happy to be breathing fresh air. Almost everywhere else in the world, the darkness of night meant the halt of all outdoor activities. If you were a villager, you barricaded yourself and your family inside your walls, made sure your weapon of choice was within reach, and prayed to whatever god you believed in for the safety of daylight. Not in the City of Towers. Even at this late hour it was bustling with activity, from the shouts of sellers in food stalls to the miserable lowing and stench of livestock.

The Plateau was lit from above by several dozen, evenly spaced, gigantic Tarakan lamps, their collective effect closely matching daylight. Like all of the city’s artifacts, the Tarakan lamps were secured by the ever-vigilant ShieldGuards. Though their faces were hidden behind black helmets, the movements of their heads indicated that they were scrutinizing the crowd. One of them spotted me, and I could almost feel his stare as he turned in my direction.

The area was too well lit, there were no shadowy corners to retreat to, so I chose a direction at random and began moving with the crowd. When I risked a glance back, the ShieldGuard was looking elsewhere. I eased my steps and circled around the area.

The cowl hid my tattoos from passersby, but it would not conceal my face completely. Eventually I would have to make eye contact, which would mean I might be remembered. I couldn’t take that chance. Not tonight.

I considered my options: my original plan was to descend to the Pit via Cart’s Way, but the road, albeit scenic, was too long to travel on foot, and I was pressed for time.

My next option, perhaps the most obvious one, was to ‘take the disc,’ meaning to board one of the Tarakan lifts from the centre of the square. Despite the fact that no one knew exactly how they worked—and several unexplained, deadly accidents—the huge oblong discs remained a popular way of connecting the Central Plateau to the rest of the city. I guess they appealed to humans’ unhealthy attraction towards danger, novelty, technology, and death. This kind of illogical behavior led me long ago to the conclusion that we are, essentially, a stupid race. Perhaps the Catastrophe was meant to clean the slate and start humanity over, but we managed to screw up even our own destruction.

One thing was sure; I possessed more than enough hard coin to pay for the lift. My LoreMaster was uncharacteristically generous with his purse when he sent me out on this venture—so generous, in fact, that I would be surprised if the Guild of Historians would be able to fund any other expedition in the foreseeable future. But I knew I should avoid taking the Tarakan lifts if I wanted to stay anonymous. Instinct told me there were too many eyes looking at me ever since I had come back to the city—and not without good reason. The woman I was looking for had amassed an impressive group of powerful enemies, but she still had a few friends in this city who could warn her. My lead was too solid to waste on amateurish behavior.

Look on the bright side, I told myself. After almost two years of travelling, chasing shadows, and following leads, you ended up back home, in the City of Towers, exactly where you started.

Sighing, I turned around and moved cautiously back through the mass of sweating humanity, away from the Plateau’s central square and into the side streets of the middle spires. It was not long before I was enveloped by the night, which for some irrational reason made me feel momentarily safer.

2

I still remember when the streets of the entire Central Plateau were lit by Tarakan lamps. Now, only a few blocks away from the ever-lit square, the back streets were almost pitch-black, and the inhabitants were of a more sinister type. I passed several groups of people huddling on street corners, standing around heating stones and open bonfires. The people were idle, drinking and talking among themselves, but I knew they were just waiting, like beasts of prey, for someone like me to come along and be dinner.

Quite early in my mission, I reached the conclusion that weapons were of no use to me. I owe many of my victories, as well as several near-death experiences, to my quick thinking and fast talking. Yet for all my self-reliance, I became painfully aware that I was walking in a dangerous part of the city with a heavy purse that jingled with every step I took. Heads turned and calculating stares followed my pace. A few of the more enterprising young men began following me, jostling for position and waiting for an opportunity to pounce.

There are not many times when my glowing red eyes are a blessing, but this was one of those occasions. I turned my head so my followers could see the fiery pupils from the depths of my cowl. Had I possessed a scythe, I could have achieved a better effect, but my glare was enough, and the shadowy entourage dispersed quickly.

I was born after the horrors of the Purges, when tattooed people like me were hunted and killed. The markings appeared on my face shortly after my thirteenth birthday. Although I was devastated, I was spared the suffering that most of my kind endured thanks to parents who were kind, loving, and—more important—wealthy. My father knew the man who is now my LoreMaster. Master Harim saw my potential, took me as an underling, and made a fine profit from my father’s coin. Notwithstanding the morning I discovered the tattoos that had appeared on my eyelids, my life until this assignment had actually been quite secure and relatively trouble free. I can honestly say I was content with my post as a secondary scribe at the Guild of Historians and looking forward to copying data and deciphering old books and salvaged Tarakan pads for the rest of my days.

Then one day, my LoreMaster sent me on this little errand. I remembered the moment I stepped out of the tower and into the real world, still believing in humanity. Well, that feeling’s definitely out of my system now. “Reading scripture can be satisfying,” my LoreMaster would tell me often, “but there is no greater adventure than going out there and finding knowledge by yourself.”

“Sounds dangerously close to Salvo-speak, LoreMaster,” I half-teased him.

There was not much about the Salvationist’s era, despite being recent, post-Catastrophe history, that my LoreMaster had not mentioned to me countless times. I could almost silently mouth the words of his next sentence.

“Very colourful cussing, I have to admit,” he chuckled. “It’s been a while since I rubbed shoulders with a Salvationist crew, but I suspect their speech is still as imaginative today. The Salvationists were right at least about one thing: there is no greater thrill, I tell you, than to salvage technology and dig information out from the ruins with your own hands.”

“Or pry it from a dead man’s hand,” I added without thinking.

LoreMaster Harim frowned, took his pipe out of his mouth and pointed it at me. “You, my dear boy, have been reading far too many Salvo-novels, and don’t even try to deny it. I know where you stash them.”

I blushed. “Purely for research,” I mumbled, “about social cohesion in times of struggle.”

The old man muttered something almost inaudible, which nevertheless sounded like Salvo-speak to me, before declaring, “Well, son, you can pack your saucy novels away. I am sending you on a research mission. Something terribly important may have just happened, and I need you to investigate it. Fully. There is a woman, an ex-Salvationist. Her name is Vincha.”

I felt my heartbeat accelerate as my LoreMaster mentioned the Salvationists.

“I need you to find this woman and find out what this Vincha knows. She is an elusive one, but I already have a few leads regarding her possible whereabouts.” Master Harim leaned over and handed me a sealed scroll. His stare was nothing short of intense. “Spare no costs. Nothing we have ever done is more important than finding out what she knows.”

The odd way he phrased it should have alerted me, but I was too surprised to be chosen for a mission by my LoreMaster to dwell on his carefully chosen words. Instead, I tried to persuade him that I was the wrong guy for the job.

“I just copy books, LoreMaster, I wouldn’t know where to begin looking for this Vincha, or how to persuade an ex-salvationist to talk to me even if I found her.”

“Nonsense.” He shoved two fat leather coin bags towards me. “You are perfect for the job. I’m sure of it.”

The first thing I did when I left the towers was to rent a room in the Green Meadow, a fancy tavern in the Central Plateau. The second thing I spent my coin on were two redheaded prostitutes. One fucked me senseless and the other stole all my coin, stabbed her coworker to death, and ran for it. It took me two weeks to track her down and three more days to get most of the coin back, but at least my LoreMaster was right about one thing: I never went back to reading those Salvo-novels again.

Many times during my search for Vincha, I had wondered about my LoreMaster’s reasons for choosing me, of all people. One would logically want to send a military expert, perhaps a Salvationist veteran or at least someone with expertise in combat, someone who, unlike myself, did not instinctively recoil from violence. Was my nomination an act of desperation? Lack of another suitable candidate? A punishment for my idling ways? Or did he already see something I never knew I had in me—a lust for adventure and a knack for quick, creative thinking when my life was in danger? At the time, I did not know the answer, but I certainly learned much in the course of my two-year-long wanderings, most of which I would pay hard metal to be able to forget.

I found myself standing suspiciously still in a dark alley of the Middle Spires. Sighing softly, I forced the memories away and concentrated on my immediate problem: finding a way down to the Pit.

And then, if I managed to stay alive, locating Vincha.

3

Even with my special sight, it was easy enough to get lost in the twisting streets of the Middle Spires. I kept walking, navigating on a hunch, looking for the signs described by a contact so inebriated she could barely stand up. Just when I was about to give up, I spotted the first of the local gang graffiti I was told to look for. I followed the graffiti signs through a series of short, narrowing lanes that were half blocked by piles of human rubbish the Council had stopped bothering to collect. I walked under two archways, one so low I had to crawl underneath it to pass. Shortly after passing through the second archway, I found myself in a cul-de-sac with a closed courtyard.

There, a group of five men clustered around a crackling bonfire, next to a poorly built wooden cabin. Behind them stood a high wall built to block people from accidentally falling down the vast drop into the lower levels of the city. The wall had a human-sized hole in it. These were the smugglers I was looking for. Now I only had to find out how fast they would drop me.

Four of the men were large; two were visibly enhanced by Tarakan augmentations on their arms, torsos, and shoulders. People called them Trolls. When augmented with the right Tarakan gear and by a skilled Gadgetier, a Troll was a formidable creature, a deadly warrior capable of inhuman feats. But by the look of their deformed bodies, these guys attached the cheap stuff, overused, unmaintained, or pieced together by an amateur Tinker.

The group turned to watch me approach, standing loose-limbed and relaxed since, after all, they outnumbered me five to one. Even so, given I had flaming red dots for eyes, their expressions naturally demonstrated caution. I pulled back my cowl.

“I’m looking for a way down,” I said.

“No problem.” The shortest guy thrust his thumb at the hole behind him. “And since you probably have wings to go with those eyes, it’ll only cost you a fiver.”

His companions chuckled and exchanged a glance.

“Assuming I don’t want to spread my wings tonight,” I asked, “how much?”

He surveyed me again, taking his time, perhaps to see how I handled the pressure. “You carrying anything?”

“Just me,” I replied, opening my cloak to show I was unarmed—which was a mistake, of course. The man—whom I judged to be the group’s leader—smiled to himself.

“Eighty in coin or kind,” he said.

It was absolute robbery and I knew it.

“Thirty,” I countered without thinking, which was my second and nearly fatal mistake. My offer was too low. I was behaving like an amateur, and they sensed it.

One of the other men took a few casual steps to the side, preparing to flank me. “I wonder if you actually could fly,” their leader said, flapping his arms for emphasis. “Perhaps the wings materialize when you’re already in the air? Maybe we should test the theory. What do you think?”

I let my eyes see through them. Their skin faded to transparency, revealing bones and muscle and, more important, knives, knuckle-dusters, power daggers, and stun grenades.

They were already closing in on me, about to pounce, when I opened my own fist to let the one closest to me see the ShieldGuard-issue marked power clip nestled there. The man actually recoiled, and before the others could react further I fished the second one from my pocket and held it between thumb and forefinger, for all to see. The power clips were obviously Tarakan original, two perfect round balls emanating a blue hue that indicated they were fully charged. The clips were the sort that powered many of the artifacts in the city and beyond, even the SuperTrucks traveling on the Tarakan highways, and could only be found deep within the mysterious nodes of the City of Towers. Long ago, when Salvationist crews roamed Tarakan Valley, power clips like these were in abundance, but nowadays things are different.

The easy brutality faded from the leader’s face, replaced by something between calculation and anxiety.

“All I want is to get down to the Pit quickly and quietly,” I said, tossing the clips over to him. He grimaced even as he plucked them from the air. As valuable as they were, being in possession of such items these days was a capital offence.

He eyed me with considerably more respect than before, then nodded and pocketed the items. The clips marked me either as a dangerous and resourceful man or the lackey of such an individual—but either way, a worthy client.

The man nearest the cabin door opened it, darted inside, and returned holding a large, alarmingly rusty metal cage, a mansized version of a singing bird’s cage I once saw in a village’s market fair. He held it with both hands, his face already red with exertion, and handed it to one of the wannabe Trolls, who picked it up with only one hand. As his shoulder brace whined in protest, the Troll tilted the cage sideways, grinning proudly at the show of strength, while his equally large colleague attached a rusty hook to the top and a very long, much-too-thin metal cable. The cage was then slammed down in front of me with a loud bang and more than a few dust clouds.

“Ever done this before?” the leader asked, and chuckled nastily when I shook my head. “Just crawl in—the hatch is quite small, but without your wings you’ll fit in nicely, and hold tight.” He indicated the wooden handlebars inside. “It’s not a long ride, but it’s bumpy.”

“Who’s waiting at the bottom?” I asked as I entered the cage.

“Three to six guys, tops.” He hesitated only briefly before deciding to share a tip. “I’d go with the bearded one. He’s an old-timer, a little wired but a tough Troll, and his metal’s still sharp.”

I nodded and grasped the unpleasantly slimy handlebars, but any thought of letting them go vanished as the cage was picked up and I was shoved unceremoniously through the hole in the wall, feet first.

“Nice doing business with ya,” I heard the leader call as I plunged into darkness.

4

It was a short but nasty free fall before the cage suddenly stopped, probably just a practical joke, but enough to make me heave the contents of my stomach. On the bright side, throwing up stopped me from crying out loud at the agonising pain the abrupt stop caused my shoulders. After what must have been a short pause—swinging in a cage high above ground tends to distort any sense of time—descent resumed at a fast but bearable pace. I still held the handles tight, as if this could somehow save me if I was suddenly dropped to my death. I decided it was better to look around instead of down. It was easy to spot two of the Tarakan lifts to my far left. They were floating majestically in full artificial light, each carrying dozens of people, propelled by mysterious Tarakan technology. I, on the other hand, was swinging in the darkness inside a rusty cage, my life hanging, literally, in the hands of an oversized and most likely overdosed Troll.

Another notable difference was that the people on the discs were sheltered by an invisible barrier from the smoke and the heat that rose from below, while I was coughing up what was left of my guts and feeling as if I were being lowered into an oven. I turned my head away from the ascending smoke and looked up. From where I was looking, the tops of the towers above me seemed as unreachable as the stars.

The low, rumbling noise, a constant feature of the Pit, signalled my descent was coming to an end.

The cage landed on the ground with a bone-crushing thud. I still managed to retain my grip on the handlebars despite my body’s painful protests. Thankfully, the cage remained upright. Fearing that the cage would ascend before I managed to clear it, I forwent dignity and let my backside lead my body out of the cage.