Полная версия:

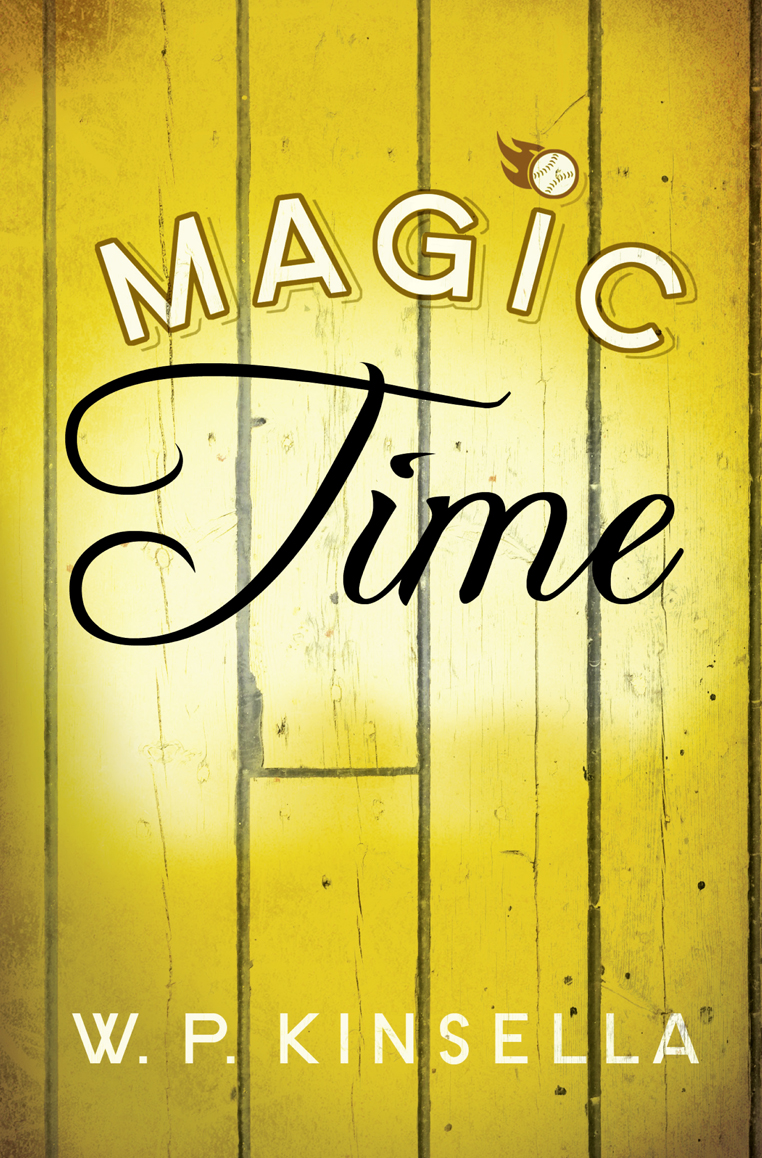

Magic Time

Magic Time

BY W. P. KINSELLA

The Friday Project An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This ebook first published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd 2014

Copyright © W. P. Kinsella 2001

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

W. P. Kinsella asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

FIRST EDITION

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007497577

Ebook Edition © July 2014 ISBN: 9780007497584

Version 2014-07-31

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

1: Judging Distances

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

2: One Road Runs Straight

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

3: Fred Noonan’s Town

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

4: Barry McMartin

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

5: Safe at Home

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

6: Magic Time

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

Also by the W.P. Kinsella

About the Publisher

Prologue

‘Mike, I think I’ve found you the perfect place to play baseball,’ my agent said, the line from his office in Los Angeles to my home in a suburb of Chicago as clear as if he was sitting across the kitchen table. My father is sitting across the kitchen table, looking expectant. On the first ring, I had reached behind my head and snatched the canary-yellow phone off the hook; it had interrupted our Scrabble game. As I listen, I make a little motion with my thumb and first finger, like a bird feeding. My father smiles.

My agent’s name is Justin Birdsong, and we’ve never met. He signed me because a year ago I looked like a top prospect for the Bigs. It’s been a long time since I heard from him. I wasn’t picked up in the most recent college draft, but Justin Birdsong said he was impressed with my credentials and would try to find me a job in minor-league baseball.

Not being drafted was a particular disappointment, though not unexpected. I was prepared for the worst, but right to the last moment I had fantasies of the Cubs drafting me onto their Triple A team in Des Moines, or the White Sox announcing that I’d be the new second-base man at their Vancouver Triple A franchise, and that I’d need only a few weeks’ seasoning before jumping to the Bigs.

I also dreamed of playing baseball in Japan, though I knew the Japanese usually signed utility outfielders who couldn’t quite cut it with a big-league club, and aging power hitters who could no longer get around on the fastball. As the draft continued I shifted my hopes to desperate teams like Oakland, Montreal, or Philadelphia – maybe they would find me a spot, any spot, in their organization. But nothing materialized.

In my junior year at Louisiana State I’d been drafted by the Montreal Expos in the fourth round, and offered an excellent signing bonus, which, after consulting with my dad, I turned down because I wanted to finish my degree in business management, and because we – we being my dad, myself, and my coaches at LSU – felt I needed another year of college experience.

Unfortunately, my final year as an LSU Tiger was one long, downward spiral. My chances of being drafted would have been better if I’d been injured – I would have had something on which to blame my decline. After being a college all-star in my junior year, my average fell from .331 to .270, my stolen bases from forty-five to nineteen, and I was caught stealing nine times. My walks declined twenty-nine percent. My play at second base, which has always been just adequate, remained that way. My promise had been as a high-average lead-off man who could also steal a ton of bases, like Rickey Henderson in his prime.

I don’t blame the pros for not drafting me. I have no excuses about my senior year but with that hope that springs eternal in every ballplayer’s heart, I feel that with a solid season of minor-league baseball this summer I’ll still be young enough for the pros to have another look at me.

After this year’s draft, Baseball America mentioned that I was the best-looking second-base man not drafted. ‘In practice, Mike Houle is as good as anyone who’s ever played the game. Perhaps with experience he’ll get a second look from big-league scouts.’

‘I can get you a contract with this team in Iowa,’ Justin Birdsong was saying. ‘League representative called this morning, one team has openings for several players, but they’re especially interested in you. Asked about you specifically. You’ll be with a semi-pro club in the Cornbelt League. They claim they play good-quality baseball. Double A quality, they assure me. They also tell me that major-league scouts make regular stops at all the ballparks in the league. You ever heard of the Cornbelt League, Mike?’

‘No. Have you?’

‘I just thought with it being in the Midwest and all …’

‘What part of Iowa is it in?’

‘East-central, the guy said. He was quite a small-town booster, could get a job as a sideshow barker any time. Gave me a sermonette on the advantages of small-town life. By the time he finished I was homesick for my folks’ little clapboard house in Arkansas – for about fifteen seconds until I remembered having to sit in the balcony of the movie theater, and that there were two sets of washrooms and water fountains at the town service stations.’

It had never occurred to me that Justin Birdsong was black.

‘Anyway, are you interested?’

‘Teams in organized baseball aren’t exactly burning up the wires to either of us.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ said Justin. ‘I’ll tell them you accept. They’ll wire you your travel money. You’re to report to Grand Mound, Iowa, day after tomorrow. You fly into Cedar Rapids and someone will meet you there. By the way, since the Cornbelt League is unaffiliated, all the teams are self-supporting. What will happen is you’ll get a base salary, and one of the local merchants will give you a job in the mornings. You’ll have your afternoons free to practice and your evenings to play baseball.’

The salary he named wasn’t enough to pay room and board, and I told him so.

‘You get free board, and you room with a local family, so that lowers your overhead considerably.’

‘Great! I get to live American Gothic.’

‘In case I didn’t mention it,’ Justin Birdsong added, ‘I only take commission on your baseball salary.’

‘What kind of morning job?’ I asked. ‘I’m a business major, I don’t want to work in a packing plant or a welding shop.’

‘They were real excited about you being a business major, one of the reasons they asked for you. The local insurance office will pay you to work for them. You’ll do fine, Mike. They’re go-getters out there, small-town proud, real excited about having you play baseball in Grand Mound.’

‘It doesn’t look as if I have much choice,’ I said. ‘I’ll be there.’

1

Judging Distances

ONE

My father is a remarkable guy. The older I get the more remarkable I find him. He does not look the way most people would imagine a gentle, self-sacrificing father should look. Dad is a large, lumpy-looking man with coarse hair down his arms and across the backs of his hands. His black hair is receding from his wide forehead, and he suffers from perpetual five o’clock shadow. His huge hands are grease-stained and scarred, his brown eyes large and sad, but they sparkle like polished oak when he smiles, a dimple breaking at the right corner of his mouth.

‘In baseball you make the same play thousands, even hundreds of thousands of times, Mike – though, like snowflakes, each one is unique. But it’s patience and persistence that carry you through. The same patience and persistence won over your mom.

‘You must have wondered how an old warthog like me managed to marry such a beautiful girl. When I was young I wasn’t handsome, I wasn’t rich, I wasn’t an athlete, and I wasn’t a hoodlum, so if I was gonna convince the girl I’d been in love with since fifth grade to marry me I was gonna have to do it on my own. Gracie only lived a few blocks away and we’d been in the same school all our lives. She considered me a friend, someone who’d always been there – like one of the old buildings downtown.

‘Final year of high school, I was already working weekends at the box factory, and your mom worked a four-hour evening shift at the old Woolworth’s. Her dad had been injured in a car accident and out of work for months. She was dating a guy named Karl, who was handsome, a fullback on the football team, and had a recklessness about him that caused girls to turn and stare when he walked down the street.

‘The one bad thing I knew about Karl was that he was never on time, and for me that was like a pitcher knowing that a batter swings at the curve in the dirt. I showed up at Woolworth’s at closing time, and stopped to chat with Gracie as she waited. I said I was on my way home from the box factory, but actually I watched the clock like a hawk and scooted out of the house in time to arrive just as Woolworth’s was closing.

‘Sometimes Karl was really late, and Gracie would get cold or tired, or both. I never said anything against the guy. I’d run across the street and get us coffee from the all-night diner, and remember to put one sugar and one and a half creams in hers, and I’d try to have a new silly joke to tell her. (Slug jokes were big then. What slug sees out the old year? Father Slime. What’s a slug’s favorite song? “As Slime Goes By.”)

‘I can’t tell you how happy I was the night when, after more than a half-hour wait, Gracie said, “To hell with him. Walk me home, Gil.”

‘The next couple of nights he was on time, but it didn’t last. This went on for months. One night I got to the store early, and bought a timing chain, car polish, and a fancy gearshift knob for an old car I was trying to get running. When Gracie came out I showed her my purchases and said, “You know, after you marry me we’re gonna have the best maintained car in the neighborhood.” Gracie laughed her merry laugh, but the glance she gave me said it all. Not a month later she came out of the store and said, “Karl and I aren’t going together any more.” By that time I was finished school. A year later we were married.

‘You know what I used to like best? After Karl showed up, whether Gracie was walking away with him, or whether she was getting into his old man’s car, she always turned and waved to me, and gave me a big smile.’

Dad would stop, sometimes there’d be a tear in his eye.

‘I miss your mom more than anybody could ever know.’

The nail and a half-inch of Dad’s right middle finger predeceased him many years ago, slashed off by a saw at the lumberyard where he’s been employed all his adult life, working his way up from stacking lumber to feeder in the sawmill to servicing the equipment, to full-fledged maintenance mechanic.

I was in first grade the day Dad lost the tip of his finger. I came home after school to find Dad in the living room rather than Mrs. Schell, who babysat my kid brother Byron and me while Dad was at work. He was sitting in his favorite chair, a leg slung over one arm of it, watching a game show on television, drinking a Tab.

‘What are you doing home?’ I asked.

‘Had a little accident, Mike,’ Dad said, turning toward me, holding up his hand so I could see his middle finger bandaged in a halo of white gauze, like snow in a coal bin in contrast to the rest of his hairy, grease-stained fingers.

‘Had a little run-in with a saw I was repairing. Forgot to unplug it.’ And he grinned, his face emitting light. ‘As you can see, I came out on the short end of the run-in, in more ways than one.’

As I came closer I saw that there was a bright red spot, like the center of a Japanese flag, on the white gauze at the end of the damaged finger. My stomach lurched like it did when Dad and I went over the top on the carnival ferris wheel. I climbed into his lap and burrowed, trembling, into his warmth, soaking up the comfortable odors of grease, tangy sawdust, and Dad’s sweat.

‘What’s the matter, Son?’

‘You’re not gonna die, are you?’

‘Of course not. It takes more than a saw to do in an old warhorse like me. Doc says I’ll be back to work in a week. In the meantime, the Cubs are in town, so I’ll pick up tickets for you and me. Maybe we’ll even take Byron to the Sunday afternoon game, though you have to take your turn ferrying him to the bathroom.’ Byron was in play school at the time.

I hugged Dad as hard as I could, burying my face in the comfort of his plaid flannel shirt, and held on until my arms hurt.

‘You don’t have to worry, Mike. Your dad’s never gonna leave you.’ And he rocked me in his arms.

I pulled myself up and kissed his blue-whiskered cheek. Dad always knew the right thing to say. Neither of us mentioned Mom, but we both knew what caused me to get all scared and shaky.

Though I claim to remember my mom, who died when I was four, I think what I remember are Dad’s stories of her. What I remember is sitting on Dad’s lap, him holding their wedding picture, an eight-by-ten that still sits on his bedside table, Mom younger than I am now, and beautiful, and Dad telling me about how they began dating, and how thrilled he was when Mom said she’d marry him.

‘Look at that, Mike, I look like a gorilla in a tuxedo. What do you suppose your mom ever saw in me?’

Or else he’d hold the family portrait one of those door-to-door photographers took not long after Byron was born. I’m sitting on Dad’s knee, dressed in yellow shorts, with a white shirt and yellow bow tie, while Mom is holding Byron wrapped in a blue blanket, all that’s visible of him a little pink circle of face. Dad would talk about the day the portrait was taken, how I was so hyper that, though you can’t see it in the picture, he had a firm grip on the back of my shorts in order to keep me from leaping off his knee.

‘Your mom had just washed your face for the third time since the photographer got there. She wiped it again, tossed the washcloth over her shoulder in the general direction of the kitchen, and said to the photographer, who looked like he’d slept in his car with a bottle of cheap wine, “Shoot us quick before any more dirt gravitates to that boy’s face!”’

Other times we’d look at dog-eared photographs from the chocolate box of photos that always sat on the mantel of the pretend fireplace in the living room. There were pictures of Mom next to a half-washed car; in jeans, shirttails flapping, as she ran laughing from a spray of water. Dad said that photo was taken before they were married, and he was on the other end of the hose. There was a color Polaroid of Mom in a yellow waitress uniform, her name, Gracie, in brown lettering above her pocket, her red hair spilling over her shoulders, smiling like she’d just received a ten-dollar tip. Her hair was so pretty in that photograph, and the photo was so clear I could see the freckles on her cheeks and the back of the hand that’s visible.

‘You boys got the best of both of us,’ Dad would say, holding up a picture of Mom smiling over a birthday cake flaming with twenty-three candles, Dad behind her chair, crouched in order to get into the picture, grinning like a fool, his fingers in a V above Mom’s head, making her look like she has rabbit ears.

‘You’re both built strong like me, with big bones, but you’re good lookin’ like your mom.’

Byron is stocky, but he has Mom’s red hair and green eyes. I’m tall and slim like Mom, but I’m strong-boned and have huge hands like Dad. My hair is reddish-brown, and has a cowlick that refuses to submit to a comb, my eyes a greeny-hazel.

Mom’s name before she married Dad was Grace Palichuk. Her grandfather had emigrated from Ukraine to work in the packing plants in Chicago. My grandfather, Dmetro Palichuk, followed in his father’s footsteps at the packing plant, but chose an Irish girl to marry, Margaret Emily O’Day, with dark rose-colored hair, green eyes, and freckles.

Our family name is Houle. My father’s name is Gilbert. Dad claimed the original Houle was a smuggler and privateer, a crewman on Jean Lafitte’s pirate ship.

‘Lafitte and his men fought for the Americans in the Battle of New Orleans and were pardoned by President Madison. I saw the pardon, or at least a copy of it, when I was a boy. That original Houle settled on Galveston Island after the Civil War, but who knows how one of his descendants got to Chicago?’

Sometimes Dad tells of a descendant of that first American Houle, a Wells Fargo driver and buffalo hunter in the Dakota Territory, who married a Black Hawk Indian woman (or Nez Perce, depending on his mood) and later became a livestock dealer before being wiped out by the great Chicago fire.

‘Your great-grandfather got mistaken for Billy the Kid. This was in some wild Colorado mining town. He was a skinny little guy with a big mustache. The town folks spotted your great-grandfather riding into town, and some young bucks tried to force him into a gunfight. He moved real careful and unbuckled his guns, let them fall to the ground. “You wouldn’t shoot an unarmed man would you?”

‘They didn’t shoot him, but they flung him in jail and decided to have a public hanging in three days. And it would have gone ahead except the real Billy the Kid rode into town. It was said he had a look about him, a rock hardness, a death-like stare. Nobody tried to provoke him into a gunfight. He made it clear he was Billy the Kid, and dared anybody to do anything about it. He even visited your great-grandfather in jail. He laughed when he saw him. “You look like a gunfighter Ned Buntline might have invented. You don’t look nothin’ like me,” Billy said.

‘“Send this little cowboy on his way,’ Billy told the sheriff, and the sheriff did as he was told. It’s said your great-grandfather never again wore a gun on his hip, and skedaddled out of Colorado like he was being chased.

‘It was one of his boys that got fleeced out of his socks in a gold-stock scam. I did see a photo of him, and he resembled your cousin Verdell in California; you know, a boy so dumb he’d sell his car for gas money.’

* * *

Mom died after being hit by a car right in front of our house. We lived in this quiet, working-class suburb of Chicago, in a wartime house, one of thousands of almost identical box-like structures built right after the Second World War to house returning servicemen and their families. The house was already twenty-five years old when my parents acquired it, just a year before Mom was killed.

Schiffert Box and Lumber, where Dad worked, was an old-fashioned company that had been founded in 1890. They hadn’t manufactured wooden boxes since the 1960s, but retained that part of the name. Dad got paid every Friday, in cash. It’s only within the last five years that Schiffert has paid by check and at two-week intervals.

Every Saturday morning Mom would do the weekly grocery shopping. On Friday evenings she would circle the loss leaders in each grocery ad or flyer, then we’d tour the supermarkets buying only the items on sale.

I was holding Byron’s hand, walking from the house, across the lawn, which Dad kept smooth as a golf green, toward our Ford Maverick, parked at the curb. The car was a shade of gold that Dad laughingly said the used-car salesman had referred to as Freudian Gilt.

The day was hot and breezy, with a few sheep-sized white clouds floating across the sky. Mom was wearing a white dress with red anchors patterned on it, white shoes, and a wide-brimmed straw hat with a red ribbon around the crown. Her family had been over for dinner the previous Sunday and Mom had borrowed some folding chairs from Grandma Palichuk, which we were going to return after shopping.

Mom had the trunk of the car open, had one chair inside and was reaching for a second when a gust of wind whipped her hat off. The hat hit the pavement beside the car, turned on edge, and rolled like a plate into the street. Mom moved instinctively to chase it.

She only took about three steps, the street was narrow and three steps was far enough for her to move right into the path of an oncoming car, driven by George Franklin, who lived only a block down the street. George Franklin didn’t even have time to apply the brakes. The car hit Mom, carried her about twenty feet down the street and deposited her on the pavement. I can still hear the sound of her head hitting the street. She died instantly, the doctor who arrived with the ambulance said.

Dad was mowing the back yard with a gas lawnmower, so he didn’t know anything unusual was going on. Someone had to go to the back yard and get him. The neighbors didn’t think to keep Byron and me away from the scene. I was sobbing because I knew what had happened was not play. Byron and I looked down at Mom, and Byron said, ‘Mama sleeping?’ and through my tears I said, ‘Yes, Mama’s sleeping.’

Then a woman in a swirling gray housedress took us each by the hand and hurried us into her house. Even though the doctor pronounced Mom dead at the scene, Dad insisted on riding with the ambulance to the hospital.

Mr. Franklin was not at fault. He wasn’t speeding. He was in the correct lane. His car was in good mechanical condition. Between the accident and the funeral, Dad walked us down the block to Mr. Franklin’s house. I held onto his right hand, and he carried Byron in the crook of his left arm.

Mr. Franklin was a tall, gaunt man with a hairline that went back like a horseshoe, a crooked nose, and sad blue eyes that protruded slightly.

‘I just want you to know I realize what happened was an accident,’ Dad said to him. ‘There was nothing you could do. Gracie should have looked before she ran into the street after her hat. You were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. It could have happened to anyone.’ Dad held out his hand to Mr. Franklin.

Mr. Franklin’s hand was trembling violently as he reached to shake my dad’s extended hand. He spoke very softly. He said he hadn’t slept since the accident, didn’t know if he’d ever sleep again.