скачать книгу бесплатно

And then the sisters left for the bus stop so that they could make the shortish ride to Elephant, as the area was known locally.

At school meanwhile, Susanne Pinkly was experiencing a rather trying first lesson of the day.

Understandably, none of the children had their minds on their timetabled lesson for first thing on a Friday, which was arithmetic; even at the best of times that was never an especially pleasant start to the final school day of the week.

This particular morning, all the whole school wanted to do was talk about the evacuation, and what their mothers and fathers had told them about it.

Susanne could completely understand this desire, but she wasn’t utterly sure what she should say to the children as she didn’t want to make a delicate situation worse, or to make any timid pupils feel even more fearful about the future than they would be already.

Susanne always kept an eye out at playtime for Jessie Ross, as she knew the bigger boys could be mean to him. She had a soft spot for Jessie as he was one of the few children who patently enjoyed their lessons (very obviously much more than his sister did, at any rate) and who would try very hard to please his teacher.

Jessie was lucky to have a sister like Connie to stand up for him, Susanne thought, although just before the Easter holidays Ted had requested to headmaster Mr Jones that Connie be moved to the other class for their forthcoming senior year at St Mark’s as he and Barbara felt that Jessie was coming to depend too much on his twin sister fighting his battles for him.

Sure enough, at the start of this autumn term the twins had been separated and now were no longer taught in the same class. Susanne had suggested she keep Connie, and that Jessie would be moved in order that he could be taken out of Larry’s daily orbit, but Mr Jones said that he thought that might make Jessie’s weakness too obvious for all to see, and that the likely result would be that Larry’s bullying would simply be replaced by another pupil becoming equally foul to Jessie.

Generally, the teachers didn’t think Larry was an out-and-out bad lad as such, because when he forgot to act the Big I Am, he seemed perfectly able to get on well with the other children, Connie having been seen playing quite amiably with him on several occasions. The teachers believed that he had a troubled home life, as his park keeper father was well known for being a bit handy with his fists when he was in his cups, while Larry’s mother bent over backward to pretend all was well, despite the occasional painful bruise suggesting otherwise. The days Larry came in to school looking a bit battered and with dried tear tracks under his eyes was when he was prone to go picking on someone smaller than him. It was rumoured that Larry’s father had been dismissed from his job the previous spring, and Susanne was sorry to note that there had been a corresponding worsening of Larry’s behaviour since then.

Having just spoken with Peggy made Susanne think afresh of Jessie, as she knew Peggy adored her niece and nephew, but that Peggy always wished that Jessie had an easier time in the playtimes and lunch breaks at school than in fact he did.

So Susanne had been intending to pay special attention today to see how he was faring now that he would be getting used to not having his sister nearby at all times. But now Susanne had to put that thought to the back of her mind as she had just had a brainwave.

She would acknowledge the forthcoming evacuation but in a more oblique way than discussing it openly. She would do this by talking about some London words and sayings that might not make much sense to people who came from outside the confines of Bermondsey.

After making sure Larry was sitting at his desk directly in her eyeline so that she could keep tabs on him, Susanne got up from her seat behind her desk at the front of the class, smoothing her second-best wool skirt over her generous hips and checking the buttons to her pretty floral blouse were correctly fastened (to her embarrassment, she’d had a mishap with a button slipping undone the day before, and had the chagrin of catching a smirking Larry and several others trying to sneak a sly glimpse of her petty).

Going to stand in front of the blackboard, Susanne began, ‘Who knows what the word “slang” means?’

A bespectacled small girl called Angela Kennedy who sometimes played with Connie after school put her hand up in the air, and when Susanne nodded in her direction, she answered, ‘Miss, is it a special word fer sumfin’ that’s all familiar, like?’

‘Sort of, Angela. Well done,’ said Susanne. ‘Slang can vary from city to town to village, and might be different whether you live in the town or the country, or whether you are a lord or a lady, or you are just like us. Slang words are those that quite often people like us might use in everyday life, rather than when we could choose the more formal word we would find in the dictionary. And I know that following our lesson last week on dictionaries, you all know very well exactly how a dictionary is organised and all the special information you can find there!’

There were a few small titters from the pupils who didn’t have the same confidence in their ability to find their way around a dictionary that their teacher apparently had in them.

Ignoring the sniggerers, Susanne went on, ‘Now, can anybody here tell me an example of a word that is said around where we live in Bermondsey, but which might not be understood over in Buckingham Palace, say, which I’m sure we’d all agree is a whole world away from what you and I know in our everyday lives, even though the palace itself is close enough that we could all bicycle there if we wanted to?’

‘Geezer,’ yelled a boyish voice from the back of the class.

‘Okay, geezer it is,’ said Susanne. ‘So, has anyone got another perhaps more polite or proper-sounding word that might be the same as geezer but that wherever you lived in the British Isles you would know that everybody who heard you say it would understand what you were talking about?’

She was hoping one of her pupils would have the nous to say ‘man’.

‘Bloke,’ said Larry.

‘Chap.’

‘Guy.’

‘Guv’ner.’

‘Guv.’

‘Anything else?’ asked Susanne.

‘Cove,’ said Jessie thoughtfully, ‘although I prefer dandy.’

Somebody gave a bark of laughter.

Jessie really didn’t help himself sometimes, Susanne thought.

‘Nancy boy,’ Larry yelled as he wriggled in his chair, trying to turn around to look at Jessie. ‘That’s you, Jessie, er, Je… Jessica Ro—’

‘Behave yourself, Larry, and keep your eyes turned to the front of the classroom at all times. Ahem. What I was hoping was that someone might say “man”,’ Susanne interrupted very sharply without pausing between her admonishment of Larry and voicing what the word was that she had been wishing a pupil would say. ‘Now, what about one of you coming up with another slang word that you can think of where several others can be used?’

‘Bog.’

‘Thank you, Larry,’ said Susanne in the sort of voice designed to shut Larry up, but that at the same time indicated to both Larry and the rest of the class that Larry wasn’t really being thanked at all and that really it was high time that he buttoned his lip.

‘Lavvy,’ somebody shouted out before Susanne could say anything else to get the lesson back to where she wanted it to be.

The class was waking up now to what Susanne was wanting from them. Almost.

‘Crapper.’

‘WC.’

‘Jakes.’

‘Karzi!’

Susanne tried not to think of what any of the posher billets might think to language such as this as she attempted and failed to conceal a smile, although she supposed they would most likely all have to ask their way to the outhouse or the toilet in their new homes at some time or other.

‘A polite term, children, remember,’ she said encouragingly.

The following silence told Susanne that ‘polite’ was quite a hurdle for some to overcome.

‘Pissoir,’ Jessie called eventually, looking down quickly, although not quickly enough that Susanne couldn’t see a cheeky cast to his eyes.

Their teacher had to turn to write on the blackboard so that her class couldn’t see the lift of her eyebrows that indicated she was suppressing a feeling lying smack bang in the centre of exasperation and humour.

East Street market was only a ten-minute stroll from Elephant along the Walworth Road, and when Elephant failed to come up to Barbara’s expectations as to the shopping opportunities, and as Peggy felt that she had a second wind as walking around was making her feel better, they decided to head towards Camberwell so that they could go to the market.

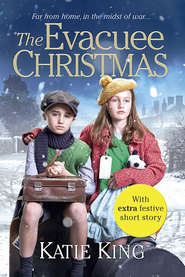

One purchase had been searched for in Elephant without success. Ted already had from his and Barbara’s honeymoon a long time ago a smallish cardboard suitcase that had long been holding Jessie’s large collection of painted lead soldiers in their colourful garb of Crimean War uniform (the softness of the metal having meant that Ted was forever straightening bent rifles or skew-whiff feather hackles on the headwear of the tiny fighters). Barbara had decided that Jessie could be sent off with his possessions carefully stowed in that suitcase, with the soldiers left behind in a drawer in his bedroom ready and waiting for him to play with after he returned from evacuation.

A second suitcase was needed, this time for Connie, as on the bus to Elephant Barbara had realised as she and Peggy talked about the evacuation that there wasn’t a guarantee that both children would be kept together and so each child needed to be catered for and packed for quite separately.

There had already been a run on all the small cases, though, as presumably other parents had been quick to snap them up for the evacuation, and this meant that only the big cases were left and they were all too large for even Peggy to lug about.

Barbara cursed roundly when she realised this, and then Peggy sat down on a step to wait as Barbara darted in and out of several shops just to be certain, before she returned empty-handed and announced that they would have to head along the Walworth Road in the direction of Camberwell in order that they could go to East Street market.

‘Barbara, I’ve been thinking,’ said Peggy as they walked along. ‘I’ve a spare cardi that Connie can take – it’ll be a bit big, I know, but it’s practically brand new, and she can roll up the cuffs, and actually she’s grown so much over the summer holidays that I don’t think it will totally swamp her. It’s that one with the little buttons on that you liked when we took the children egg-hunting in the park at Easter.’

Her sister smiled her thanks, and promised that, her treat, they would stop for a bun and a hot drink after they had finished their shopping.

At the knitting shop, Barbara went to choose some four-ply to knit Jessie a pullover – she was a very fast knitter, and although she didn’t think she’d have enough time before the children left on Monday to finish the sleeves to make Jessie a long-sleeved winter jumper, she thought she could manage a pullover in the time she had.

‘Peg, help me choose the colour that is closest to that of the cardi you’re thinking of for our Connie,’ asked Barbara.

When Peggy said it was quite a bright green, Barbara then put down the skein of pale grey wool she had been holding, and chose the one that most approximated the green of the cardi for Jessie’s woolly, so that the twins’ new knitwear would more or less match.

Peggy bought some dark yellow wool, as she thought she could make Connie a woollen hat, as if they were going to be out in the far reaches of a country area where they’d be exposed to the elements, it would be perishingly cold in a couple of months, and Peggy knew for a fact (although she doubted Barbara did) that Connie’s hat from the previous winter was lying somewhere on top of one of the warehouse roofs on the docks. Peggy knew this because she had seen Connie throw it up there when she was showing off to Larry and his chums as to her hurling prowess on the last day of the spring term just after the school had broken up for the holidays.

When Connie realised her aunt had seen her wondrous overarm lob, Connie begged Peggy not to say anything to her mother, and Peggy had agreed, as Connie’s hat had had a tough winter, having often been used to carry marbles and all sorts of other things, many of them filthy and sharply barbed, and it had got distinctly scruffy to the point that it wouldn’t in any case meet Barbara’s exacting standards as to what ‘would do’ for another winter.

Peggy knew that Jessie had a grey worsted peaked cap that she didn’t doubt that he would be taking on his evacuation. It wouldn’t be of very much use in the keeping-warm sense when the harsh winter weather really set in, but she couldn’t imagine him wearing anything else that might be cosier (i.e., anything knitted) in case this led to a new and possibly more vicious spate of teasing.

As they were about to leave the wool shop, Barbara saw some homemade knitted toys that were piled in a large wicker basket close to the shop door, and so she chose a small grey teddy for Jessie and a black and white panda for Connie. ‘I know they’re too big really for toys like this, but if they’re homesick they can take these into their beds for a quick cuddle,’ Barbara explained.

‘That’s a good idea. And why don’t you give the toys a dab of your best scent too and wrap them tightly in paper to keep the pong in, and then there’ll be a smell of you when they unwrap them?’ said Peggy, to which her sister nodded agreement.

Then she reminded Barbara that the children would need new scarves and so Barbara bought some thick navy wool to knit them some, and some thinner wool in the same colour to make them both some gloves, saying luckily the weather was still summery and so she could get to this knitting once the children had left, as she was sure they’d love to receive a parcel from home.

Just then Peggy spied a machine in the corner, clattering away nineteen to the dozen – she knew what it was: a name-tape maker.

The headmaster had requested that all the children’s clothing was labelled with their names, and although at first the shopkeeper said his wife was too busy with other children’s names, he then looked at all that Peggy and Barbara were just about to buy from him and, with a sigh of defeat, he said that as a special favour the name tapes could be ready first thing in the morning if Barbara wanted to pay the ‘premium rate’ for a special service.

For a moment Barbara baulked as she didn’t approve of anyone taking advantage of a situation where a customer had no choice, simply for a shopkeeper to earn themselves an extra few pennies when they had their customers over a barrel. But then she relented as the name tapes would save her so much time, otherwise she would have to embroider the children’s initials on each garment.

With only the smallest discernible huff of irritation, Barbara looked the shopkeeper in the eye and said she would be happy to pay the premium rate, at which point Peggy turned her head sharply towards her sister as an indication of how unusual an acquiescence this was. The shopkeeper had the grace to look a bit uncomfortable in the glare of Barbara’s unnerving stare as carefully he jotted down the names of Jessie and Connie. Peggy didn’t like to think what would happen if he made a mistake in the spelling.

A little further down the market, there was a luggage stall that had lots of bags and cases piled up. It too had run out of the small cardboard suitcases that Barbara really wanted, but fortunately it did have a wide collection of holdalls and so Barbara chose a sturdy blue one for Connie’s things to be stowed away inside.

Another stall was selling children’s clothing and from here Barbara bought the children new vests, pants and socks, and a couple of shirts for Jessie (one grey and one blue) and a pretty sky-blue checked dress for Connie as well as a smart woollen red herringbone coat for her too.

‘Jessie had a new mackintosh last year that’s still got plenty of room for him, and although this red coat is going to be big on Connie, at least she’ll be able to grow into it,’ said Barbara, as she asked the stallholder to wrap the coat in brown paper, which he tied up with string, while all the other new purchases were carefully folded and placed in the holdall after it had had a good shake-out upside down with its zip opened, just to make sure there was no dust lurking inside. ‘And they have their school blazers that they can wear under their coats if it gets frosty or snowy. We’re so lucky being able to make sure they go with everything they need – I know some families are having to penny-pinch to send them away with even one decent set of clothes, let alone enough to keep them warm if they are away long enough for the bad winter weather to come.’

Peggy looked up at the clear and sunny sky that had only the smallest and fluffiest of clouds dotted here and there, and thought it was very hard to imagine that it might be snowing before too long.

Before she could get too lost in her thoughts, Peggy made herself rally and concentrate on what extra she might need to take for her own needs. She bought herself some new underwear, three pairs of natural tan fully fashioned Du Pont stockings (her favourite) and a pair of smart new gloves, and these too were placed into Connie’s holdall. Luckily it turned out to be a very forgiving bag as it seemed able to contain much more than it looked as if it could, which was just as well considering that Peggy had forgotten her own shopping basket, she had been so caught up in the drama of seeing Bill off.

The sisters felt as if they had earned their toasted teacake and Camp coffee, and so they went into a small café on the way to the bus stop.

As they sat down, Peggy felt once more that she was about to cry.

Barbara saw immediately that it had all got a bit much for her, and so she said, ‘Let it out, Peg, nobody’s going to mind. It must have been very difficult for you to watch Bill go off.’

Being given permission to have a quick sob did the trick, Peggy realised a minute later, as she’d been able after all to keep her tears in check.

In fact, she was now smiling as she told Barbara for the second time how daft Bill had looked as he had angled his head so that he could shout to her as he was driven by in the charabanc with Reece Pinkly chuckling along beside him.

There was a call from behind the counter, and as Barbara stood up to go and get their teacakes, she opened her handbag to retrieve something, and then pushed a small white paper bag in her sister’s direction. This was a surprise to Peggy, and she couldn’t prevent a cry of pleasure when inside she saw a brand-new Coty lipstick in her favourite Cardinal Red.

‘I nipped into the chemist’s while you were having a rest on that step at Elephant,’ said Barbara as she passed Peggy her teacake. ‘Pregnant or not, we can’t have you letting the side down outside London, and showing them we don’t know how to make ourselves presentable, now, can we?’

Chapter Seven (#ulink_758f1b06-f635-52b8-95c3-8991d4b15a6b)

The hours raced by over the weekend as everybody did their best to get ready for Monday morning.

Connie had to be drafted in to help Barbara sew the last few name tapes in discreet places on the various items of clothing for herself and her brother as this turned out to be a much more fiddly job than anyone had anticipated, or at least it was at the speed they were trying to attach them.

Barbara, while a good knitter, was impatient when sewing at the best of times, which wasn’t helpful in a situation like this when they were working against the clock.

Often when standing behind the counter at Mrs Truelove’s haberdasher’s, when local women were asking advice on the merits of one thread over another for particular fabrics, she could barely withhold a private ironic grimace at the thought of her not practising what she preached, which was nearly always ‘feel your way into it, and go slowly until you are used to how much the thread and the fabric like one another’.

Luckily Connie wasn’t a bad seamstress in spite of being so young. In fact, for the previous Christmas, she had designed and made Barbara a cloth carry-all that had various pockets and compartments for her mother to keep her knitting needles and patterns tidy in. The quality of both the design and the stitching was so good that Barbara felt a sudden flip of envy as she knew her daughter’s skills with cotton and needle had now surpassed her own by far, and Connie was very quick and rhythmical too in her sewing, which meant that all the stitches were a uniform size that already looked to be verging on the professional.

The men of the Ross family weren’t getting away with sitting around idly either over the weekend, Barbara was making sure, as from the Friday afternoon there seemed a never-ending list of things that she wanted either Ted or Jessie, or sometimes both, to go and get from the shops or round about.

It was the first time the children had gone a whole weekend without being let out to play, and they felt very grown up.

They also wanted to stay close to Ted and Barbara, now that it was beginning to sink in that they really were going to be evacuated first thing on Monday morning, and by that evening they would be spending their very first night in beds other than at number five Jubilee Street.

When the twins caught a moment together they couldn’t help but try to guess what it might be like, wherever they were going. Connie said she rather hoped their billet would have a dog for them to play with, while Jessie said he wished there’d be lots of food and not too many rules. Then they’d grow quiet, thinking of all the things they loved about their home and Bermondsey.

According to Barbara, the purchases of the various things they needed to buy were to be allocated as follows:

Toothbrushes and tubes of toothpaste for each child: Jessie

Soap, ditto: Jessie

Shoe polish, plus soft yellow dusters to shine the shoes, ditto (they hadn’t been asked to take this, but Barbara insisted a shoe-cleaning kit was ‘an essential’): Jessie

Notebooks and pencils, ditto (again, not on the list, but Barbara was firm): Ted

New combs, ditto: Jessie

Postcards and stamps, ditto: Ted

Knives, forks, spoons and tin mugs, ditto: Ted and Jessie

Raisins and prunes, ditto: Ted and Jessie

Large labels with string for their names and schools to be written on, along with their destination, ditto: Connie

Two containers for the butter, ditto: Connie

And so on, with Barbara’s list ending up quite possibly four times as long.

Barbara and Ted, and Connie and Jessie were heartily sick and tired of it all well before they had sorted everything out that needed doing.