Полная версия:

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

The Complete Tawny Man

Trilogy:

Fool’s Errand

The Golden Fool

Fool’s Fate

Robin Hobb

COPYRIGHT

HarperVoyager

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.com

Fool’s Errand Copyright © Robin Hobb 2001

The Golden Fool Copyright © Robin Hobb 2002

Fool’s Fate Copyright © Robin Hobb 2003

Robin Hobb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2013 ISBN: 9780007532117

Version 2018-06-20

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

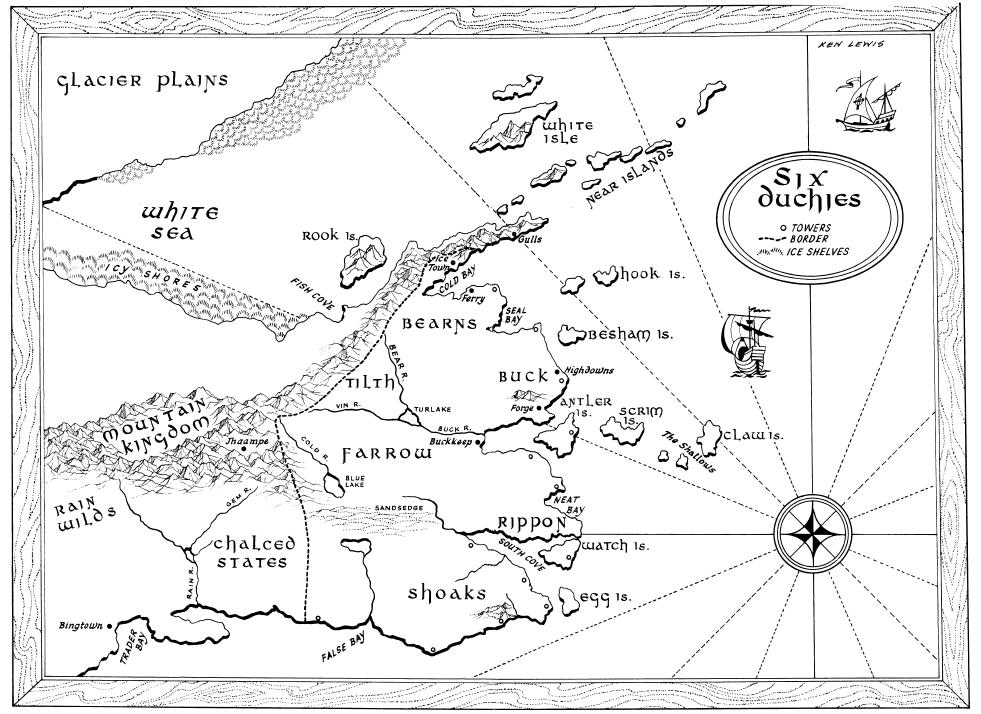

Map

Fool’s Errand

The Golden Fool

Fool’s Fate

About the Author

Also by Robin Hobb

Copyright

About the Publisher

MAP

Fool’s Errand

Book One of The Tawny Man

Robin Hobb

DEDICATION

For Ruth and her Stripers,

Alexander and Crusades.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

ONE : Chade Fallstar

TWO : Starling

THREE : Partings

FOUR : The Hedge-Witch

FIVE : The Tawny Man

SIX : The Quiet Years

SEVEN : Heart of a Wolf

EIGHT : Old Blood

NINE : Dead Man’s Regrets

TEN : A Sword and a Summons

ELEVEN : Chade’s Tower

TWELVE : Charms

THIRTEEN : Bargains

FOURTEEN : Laurel

FIFTEEN : Galeton

SIXTEEN : Claws

SEVENTEEN : The Hunt

EIGHTEEN : Fool’s Kiss

NINETEEN : The Inn

TWENTY : Stones

TWENTY-ONE : Dutiful

TWENTY-TWO : Choices

TWENTY-THREE : The Beach

TWENTY-FOUR : Confrontations

TWENTY-FIVE : Ransom

TWENTY-SIX : Sacrifice

TWENTY-SEVEN : Lessons

TWENTY-EIGHT : Homecoming

TWENTY-NINE : Buckkeep Town

Epilogue

Copyright

ONE Chade Fallstar

Is time the wheel that turns, or the track it leaves behind?

Kelstar’s Riddle

He came one late, wet spring, and brought the wide world back to my doorstep. I was thirty-five that year. When I was twenty, I would have considered a man of my current age to be teetering on the verge of dotage. These days, it seemed neither young nor old to me, but a suspension between the two. I no longer had the excuse of callow youth, and I could not yet claim the eccentricities of age. In many ways, I was no longer sure what I thought of myself. Sometimes it seemed that my life was slowly disappearing behind me, fading like footprints in the rain, until perhaps I had always been the quiet man living an unremarkable life in a cottage between the forest and the sea.

I lay abed that morning, listening to the small sounds that sometimes brought me peace. The wolf breathed steadily before the softly crackling hearth-fire. I quested towards him with our shared Wit-magic, and gently brushed his sleeping thoughts. He dreamed of running over snow-smooth rolling hills with a pack. For Nighteyes, it was a dream of silence, cold and swiftness. Softly I withdrew my touch and left him to his private peace.

Outside my small window, the returning birds sang their challenges to one another. There was a light wind, and whenever it stirred the trees, they released a fresh shower of last night’s rain to patter on the wet sward. The trees were silver birches, four of them. They had been little more than sticks when I had planted them. Now their airy foliage cast a pleasant light shade outside my bedroom window. I closed my eyes and could almost feel the flicker of the light on my eyelids. I would not get up, not just yet.

I had had a bad evening the night before, and had had to face it alone. My boy, Hap, had gone off gallivanting with Starling almost three weeks ago, and still had not returned. I could not blame him. My quiet reclusive life was beginning to chafe his young shoulders. Starling’s stories of life at Buckkeep, painted with all the skill of her minstrel ways, created pictures too vivid for him to ignore. So I had reluctantly let her take him to Buckkeep for a holiday, that he might see for himself a Springfest there, eat a carris seed-topped cake, watch a puppet show, mayhap kiss a girl. Hap had grown past the point where regular meals and a warm bed were enough to content him. I had told myself it was time I thought of letting him go, of finding him an apprenticeship with a good carpenter or joiner. He showed a knack for such things, and the sooner a lad took to a trade, the better he learned it. But I was not ready to let him go just yet. However, for now I would enjoy a month of peace and solitude, and recall how to do things for myself. Nighteyes and I had each other for company. What more could we need?

Yet no sooner were they gone than the little house seemed too quiet. The boy’s excitement at leaving had been too reminiscent of how I myself had once felt about Springfests and the like. Puppet shows and carris seed cakes and girls to kiss all brought back vivid memories I thought I had long ago drowned. Perhaps it was those memories that birthed dreams too vivid to ignore. Twice I had awakened sweating and shaking with my muscles clenched. I had enjoyed years of respite from such unquiet, but in the past four years, my old fixation had returned. Of late, it came and went, with no pattern I could discern. It was almost as if the old Skill-magic had suddenly recalled me and was reaching to drag me out of my peace and solitude. Days that had been as smooth and alike as beads on a string were now disrupted by its call. Sometimes the Skill-hunger ate at me as a canker eats sound flesh. Other times, it was no more than a few nights of yearning, vivid dreams. If the boy had been home, I probably could have shaken off the Skill’s persistent plucking at me. But he was gone, and so yesterday evening, I had given in to the unvanquished addiction such dreams stirred. I had walked down to the sea cliffs, sat on the bench my boy had made for me, and stretched out my magic over the waves. The wolf had sat beside me for a time, his look one of ancient rebuke. I tried to ignore him. ‘No worse than your penchant for bothering porcupines,’ I pointed out to him.

Save that their quills can be pulled out. What stabs you only goes deeper and festers. His deep eyes glanced past mine as he shared his pointed thoughts.

Why don’t you go hunt a rabbit?

You’ve sent the boy and his bow away.

‘You could run it down yourself, you know. Time was when you did that.’

Time was when you went with me to hunt. Why don’t we go and do that, instead of this fruitless seeking? When will you accept that there is no one out there who can hear you?

I just have to … try.

Why? Is my companionship not enough for you?

It is enough for me. You are always enough for me. I opened myself wider to the Wit-bond we shared and tried to let him feel how the Skill tugged at me. It is the magic that wants this, not me.

Take it away. I do not want to see that. And when I had closed that part of myself to him, he asked piteously, Will it never leave us alone?

I had no answer to that. After a time, the wolf lay down, put his great head on his paws and closed his eyes. I knew he would stay by me because he feared for me. Twice the winter before last, I had over-indulged in Skilling, burning physical energy in that mental reaching until I had been unable even to totter back to the house on my own. Nighteyes had had to fetch Hap both times. This time we were alone.

I knew it was foolish and useless. I also knew I could not stop myself. Like a starving man who eats grass to appease the terrible emptiness in his belly, so I reached out with the Skill, touching the lives that passed within my reach. I could brush their thoughts and temporarily appease the great craving that filled me with emptiness. I could know a little of the family out for a windy day’s fishing. I could know the worries of a captain whose cargo was just a bit heavier than his ship would carry well. The mate on the same ship was worried about the man her daughter wished to marry; he was a lazy fellow for all of his pretty ways. The ship’s boy was cursing his luck; they’d get to Buckkeep Town too late for Springfest. There’d be nothing left but withered garlands browning in the gutters by the time he got there. It was always his luck.

There was a certain sparse distraction to these knowings. It restored to me the sense that the world was larger than the four walls of my house, larger even than the confines of my own garden. But it was not the same as true Skilling. It could not compare to that moment of completion when minds joined and one sensed the wholeness of the world as a great entity in which one’s own body was no more than a mote of dust.

The wolf’s firm teeth on my wrist had stirred me from my reaching. Come on. That’s enough. If you collapse down here, you’ll spend a cold wet night. I am not the boy, to drag you to your feet. Come on, now.

I had risen, seeing blackness at the edges of my vision when I first stood. It had passed, but not the blackness of spirit that came in its wake. I had followed the wolf back through the gathering dark beneath the dripping trees, back to where my fire had burned low in the hearth and the candles guttered on the table. I made myself elfbark tea, black and bitter, knowing it would only make my spirit more desolate, but knowing also that it would appease my aching head. I had burned away the nervous energy of the elfbark by working on a scroll describing the stone game and how it was played. I had tried several times before to complete such a treatise and each time given it up as hopeless. One could only learn to play it by playing it, I told myself. This time I was adding to the text a set of illustrations, to show how a typical game might progress. When I set it aside just before dawn was breaking, it seemed only the stupidest of my latest attempts. I went to bed more early than late.

I awoke to half the morning gone. In the far corner of the yard, the chickens were scratching and gossiping among themselves. The rooster crowed once. I groaned. I should get up. I should check for eggs and scatter a handful of grain to keep the poultry tamed. The garden was just sprouting. It needed weeding already, and I should re-seed the row of fesk that the slugs had eaten. I needed to gather some more of the purple flag while it was still in bloom; my last attempt at an ink from it had gone awry, but I wanted to try again. There was wood to split and stack. Porridge to cook, a hearth to sweep. And I should climb the ash tree over the chicken house and cut off that one cracked limb before a storm brought it down on the chicken house itself.

And we should go down to the river and see if the early fish runs have begun yet. Fresh fish would be good. Nighteyes added his own concerns to my mental list.

Last year you nearly died from eating rotten fish.

All the more reason to go now, while they are fresh and jumping. You could use the boy’s spear.

And get soaked and chilled.

Better soaked and chilled than hungry.

I rolled over and went back to sleep. So I’d be lazy one morning. Who’d know or care? The chickens? It seemed but moments later that his thoughts nudged me.

My brother, awake. A strange horse comes.

I was instantly alert. The slant of light in my window told me that hours had passed. I rose, dragged a robe over my head, belted it, and thrust my feet into my summer shoes. They were little more than leather soles with a few straps to keep them on my feet. I pushed my hair back from my face. I rubbed my sandy eyes. ‘Go see who it is,’ I bid Nighteyes.

See for yourself. He’s nearly to the door.

I was expecting no one. Starling came thrice or four times a year, to visit for a few days and bring me gossip and fine paper and good wine, but she and Hap would not be returning so soon. Other visitors to my door were rare. There was Baylor who had his cot and hogs in the next vale, but he did not own a horse. A tinker came by twice a year. He had found me first by accident in a thunderstorm when his horse had gone lame and my light through the trees had drawn him from the road. Since his visit, I’d had other visits from similar travellers. The tinker had carved a curled cat, the sign of a hospitable house, on a tree beside the trail that led to my cabin. I had found it, but left it intact, to beckon an occasional visitor to my door.

So this caller was probably a lost traveller, or a road-weary trader. I told myself a guest might be a pleasant distraction, but the thought was less than convincing.

I heard the horse halt outside and the small sounds of a man dismounting.

The grey one, the wolf growled low.

My heart near stopped in my chest. I opened the door slowly as the old man was reaching to knock at it. He peered at me, and then his smile broke forth. ‘Fitz, my boy. Ah, Fitz!’

He reached to embrace me. For an instant, I stood frozen, unable to move. I did not know what I felt. That my old mentor had tracked me down after all these years was frightening. There would be a reason, something more than simply seeing me again. But I also felt that leap of kinship, that sudden stirring of interest that Chade had always roused in me. When I had been a boy at Buckkeep, his secret summons would come at night, bidding me climb the concealed stair to his lair in the tower above my room. There he mixed his poisons and taught me the assassin’s trade and made me irrevocably his. Always my heart had beat faster at the opening of that secret door. Despite all the years and the pain, he still affected me that way. Secrets and the promise of adventure clung to him.

So I found myself reaching out to grasp his stooping shoulders and pull him to me in a hug. Skinny, the old man was getting skinny again, as bony as he had been when I first met him. But now I was the recluse in the worn robe of grey wool. He was dressed in royal blue leggings and a doublet of the same with slashed insets of green that sparked off his eyes. His riding boots were black leather, as were the soft gloves he wore. His cloak of green matched the insets in his doublet and was lined with fur. White lace spilled from his collar and sleeves. The scattered scars that had once shamed him into hiding had faded to a pale speckling on his weathered face. His white hair hung loose to his shoulders and was curled above his brow. There were emeralds in his earrings, and another one set squarely in the centre of the gold band at his throat.

The old assassin smiled mockingly as he saw me take in his splendour. ‘Ah, but a Queen’s Counsellor must look the part, if he is to get the respect both he and she deserve in his dealings.’

‘I see,’ I said faintly, and then, finding my tongue, ‘Come in, do, come in. I fear you will find my home a bit ruder than what you have obviously become accustomed to, but you are welcome all the same.’

‘I did not come to quibble about your house, boy. I came to see you.’

‘Boy?’ I asked him quietly as I smiled and showed him in.

‘Ah, well. To me, always, perhaps. It is one of the advantages of age, I can call anyone almost anything I please, and no one dares challenge me. Ah, you have the wolf still, I see. Nighteyes, was it? Up in years a bit now; I don’t recall that white on your muzzle. Come here now, there’s a good fellow. Fitz, would you mind seeing to my horse? I’ve been all morning in the saddle, and spent last night at a perfectly wretched inn. I’m a bit stiff, you know. And just bring in my saddlebags, would you? There’s a good lad.’

He stooped to scratch the wolf’s ears, his back to me, confident I would obey him. And I grinned and did. The black mare he’d ridden was a fine animal, amiable and willing. There is always a pleasure to caring for a creature of that quality. I watered her well, gave her some of the chickens’ grain and turned her into the pony’s empty paddock. The saddlebags that I carried back to the house were heavy and one sloshed promisingly.

I entered to find Chade in my study, sitting at my writing desk, poring over my papers as if they were his own. ‘Ah, there you are. Thank you, Fitz. This, now, this is the stone game, isn’t it? The one Kettle taught you, to help you focus your mind away from the Skill-road? Fascinating. I’d like to have this one when you are finished with it.’

‘If you wish,’ I said quietly. I knew a moment’s unease. He tossed out words and names I had buried and left undisturbed. Kettle. The Skill-road. I pushed them back into the past. ‘It’s not Fitz any more,’ I said pleasantly. ‘It’s Tom Badgerlock.’

‘Oh?’

I touched the streak of white in my hair from my scar. ‘For this. People remember the name. I tell them I was born with the white streak, and so my parents named me.’

‘I see,’ he said noncommittally. ‘Well, it makes sense, and it’s sensible.’ He leaned back in my wooden chair. It creaked. ‘There’s brandy in those bags, if you’ve cups for us. And some of old Sara’s ginger cakes … I doubt you’d expect me to remember how fond you were of those. Probably a bit squashed, but it’s the taste that matters with those.’ The wolf had already sat up. He came to place his nose on the edge of the table. It pointed directly at the bags.

‘So. Sara is still cook at Buckkeep?’ I asked as I looked for two presentable cups. Chipped crockery didn’t bother me, but I was suddenly reluctant to set it out for Chade.

Chade left the study and came to my kitchen table. ‘Oh, not really. Her old feet bother her if she stands too long. She has a big cushioned chair, set up on a platform in the corner of the kitchen. She supervises from there. She cooks the things she enjoys cooking, the fancy pastries, the spiced cakes, and the sweets. There’s a young man named Duff does most of the daily cooking now.’ He was unpacking the saddlebags as he spoke. He set out two bottles marked as Sandsedge brandy. I could not remember the last time I’d tasted that. The ginger cakes, a bit squashed as foretold, emerged, spilling crumbs from the linen he’d wrapped them in. The wolf sniffed deeply, then began salivating. ‘His favourites, too, I see,’ Chade observed dryly, and tossed him one. The wolf caught it neatly and carried it off to devour on the hearthrug.

The saddlebags gave up their other treasures quickly. A sheaf of fine paper, pots of blue, red and green inks. A fat ginger root, just starting to sprout, ready to be potted for the summer. Some packets of spices. A rare luxury for me, a round ripe cheese. And in a little wooden chest, other items, hauntingly strange in their familiarity. Small things I had thought long lost to me. A ring that had belonged to Prince Rurisk of the Mountain Kingdom. The arrowhead that had pierced the Prince’s chest and nearly been the death of him. A small carved box, made by my hands years ago, to contain my poisons. I opened it. It was empty. I put the lid back on the box and set it down on the table. I looked at him. He was not just one old man come to visit me. He brought all of my past trailing along behind him as an embroidered train follows a woman into a hall. When I let him in my door, I had let in my old world with him.

‘Why?’ I asked quietly. ‘Why, after all these years, have you sought me out?’

‘Oh, well.’ Chade drew a chair up to the table and sat down with a sigh. He unstoppered the brandy and poured for both of us. ‘A dozen reasons. I saw your boy with Starling. And I knew at once who he was. Not that he looks like you, any more than Nettle looks like Burrich. But he has your mannerisms, your way of holding back and looking at a thing, with his head cocked just so before he decides whether he’ll be drawn in. He put me so much in mind of you at that age that …’

‘You’ve seen Nettle,’ I cut in quietly. It was not a question.

‘Of course,’ he replied as quietly. ‘Would you like to know about her?’

I did not trust my tongue to answer. All my old cautions warned me against evincing too great an interest in her. Yet I felt a prickle of foreknowledge that Nettle, my daughter whom I had never seen except in visions, was the reason Chade had come here. I looked at my cup and weighed the merits of brandy for breakfast. Then I thought again of Nettle, the bastard I had unwillingly abandoned before her birth. I drank. I had forgotten how smooth Sandsedge brandy was. Its warmth spread through me as rapidly as youthful lust.

Chade was merciful, in that he did not force me to voice my interest. ‘She looks much like you, in a skinny, female way,’ he said, then smiled to see me bristle. ‘But, strange to tell, she resembles Burrich even more. She has more of his mannerisms and habits of speech than any of his five sons.’

‘Five!’ I exclaimed in astonishment.

Chade grinned. ‘Five boys, and all as respectful and deferential to their father as any man could wish. Not at all like Nettle. She has mastered that black look of Burrich’s and gives it right back to him when he scowls at her. Which is seldom. I won’t say she’s his favourite, but I think she wins more of his favour by standing up to him than all the boys do with their earnest respect. She has Burrich’s impatience, and his keen sense of right and wrong. And all your stubbornness, but perhaps she learned that from Burrich as well.’

‘You saw Burrich then?’ He had raised me, and now he raised my daughter as his own. He’d taken to wife the woman I’d seemingly abandoned. They both thought me dead. Their lives had gone on without me. To hear of them mingled pain with fondness. I chased the taste of it away with Sandsedge brandy.

‘It would have been impossible to see Nettle, save that I saw Burrich also. He watches over her like, well, like her father. He’s well. His limp has not improved with the years. But he is seldom afoot, so it seems to bother him little. It is horses with him, always horses, as it always was.’ He cleared his throat. ‘You do know that the Queen and I saw to it that both Ruddy and Sooty’s colt were given over to him? Well, he’s founded his livelihood on those two stud horses. The mare you unsaddled, Ember, I got her from him. He trains as well as breeds horses now. He will never be a wealthy man, for the moment he has a coin to spare, it goes for another horse or to buy more pasturage. But when I asked him how he did, he told me, “well enough.”’