Полная версия:

The Complete Soldier Son Trilogy: Shaman’s Crossing, Forest Mage, Renegade’s Magic

The Complete Soldier Son Trilogy

Shaman’s Crossing Book One

Forest Mage Book Two

Renegade’s Magic Book Three

Robin Hobb

Copyright

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Shaman’s Crossing © Robin Hobb 2005

Forest Mage © Robin Hobb 2006

Renegade’s Magic © Robin Hobb 2007

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers

Robin Hobb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007532148

Version: 2018–07–31

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

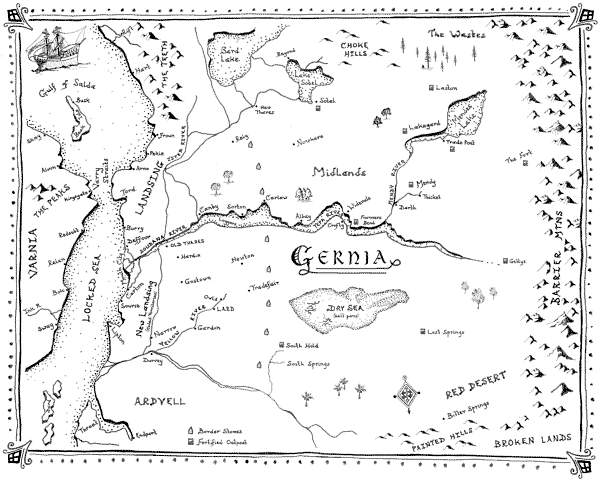

Map

Shaman’s Crossing

Forest Mage

Renegade’s Magic

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map

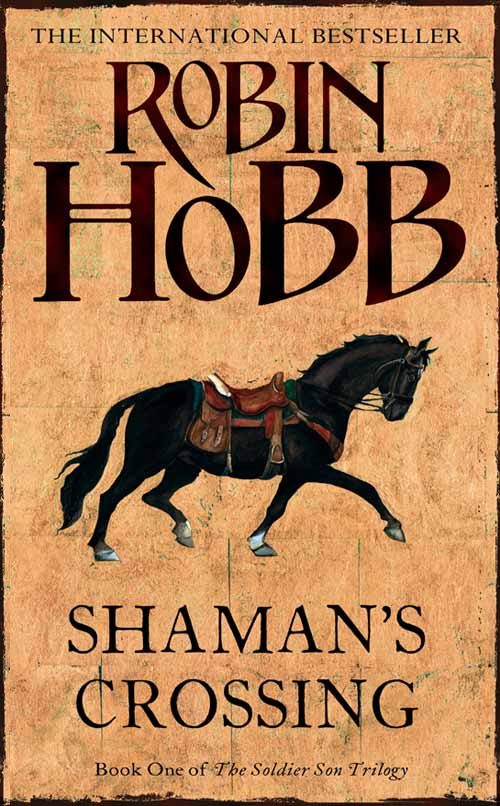

Shaman’s Crossing

Book One of the Soldier Son Trilogy

Robin Hobb

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by Voyager 2006

Copyright © Robin Hobb 2005

Cover illustration © Jackie Morris

Map by Andrew Ashton

Robin Hobb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007196128

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2008 ISBN: 9780007236886

Version: 2018–07–31

Dedication

To Caffeine and Sugar, my companions through many a long night of writing.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

One: Magic and Iron

Two: Harbinger

Three: Dewara

Four: Crossing the Bridge

Five: The Return

Six: Sword and Pen

Seven: Journey

Eight: Old Thares

Nine: The Academy

Ten: Classmates

Eleven: Initiation

Twelve: Letters From Home

Thirteen: Bessom Gord

Fourteen: Cousin Epiny

Fifteen: Séance

Sixteen: A Ride in the Park

Seventeen: Tiber

Eighteen: Accusations

Nineteen: Intervention

Twenty: Crossing

Twenty-One: Carnival

Twenty-Two: Disgrace

Twenty-Three: Plague

Twenty-Four: Vindication

Acknowledgments

ONE

Magic and Iron

I remember well the first time I saw the magic of the plainspeople.

I was eight and my father had taken me with him on a trip to the outpost on Franner’s Bend. We had arisen before the dawn for the long ride; the sun was just short of standing at noon when we finally saw the flag waving over the walls of the outpost by the river. Once, Franner’s Bend had been a military fort on the contested border between the plainspeople and the expanding Kingdom of Gernia. Now it was well within the Gernian border, but some of its old martial glory persisted. Two great cannons guarded the gates, but the trade stalls set up against the mud-plastered stockade walls behind them dimmed their ferocity. The trail we had followed from Widevale now joined a road that picked its way among the remains of mud-brick foundations. Their roofs and walls were long gone, leaving the shells gaping at the sky like empty tooth sockets in a skull. I looked at them curiously as we passed, and dared a question. ‘Who used to live here?’

‘Plainspeople,’ Corporal Parth said. His tone said that was his full reply. Rising early did not suit his temperament, and I suspected already that he blamed me for having to get out of bed so early.

I held my tongue for a time, but then the questions burst out of me. ‘Why are all the houses broken and gone? Why did they leave? I thought the plainspeople didn’t have towns. Was this a plainspeople town?’

‘Plainspeople don’t have towns, they left because they left, and the houses are broken because the plainspeople didn’t know how to build any better than a termite does.’ Parth’s low-voiced answer implied that I was stupid for asking.

My father has always had excellent hearing. ‘Nevare,’ he said.

I nudged my horse to move up alongside my father’s taller mount. He glanced at me once, I think to be sure I was listening, and then said, ‘Most plainspeople did not build permanent towns. But some folk, like the Bejawi, had seasonal settlements. Franner’s Bend was one of them. They came with their flocks during the driest part of the year, for there would be grazing and water here. But they didn’t like to live for long in one place, and so they didn’t build to last. At other times of the year, they took their flocks out onto the plains and followed the grazing.’

‘Why didn’t they stay here and build something permanent?’

‘It wasn’t their way, Nevare. We cannot say they didn’t know how, for they did build monuments in various locations that were significant to them, and those monuments have weathered the tests of time very well. One day I shall take you to see the one named Dancing Spindle. But they did not make towns for themselves as we do, or devise a central government or provide for the common good of their people. And that was why they remained a poor, wandering folk, prey to the Kidona raiders and to the vagaries of the seasons. Now that we have settled the Bejawi and begun to teach them how to have permanent villages and schools and stores, they will learn to prosper.’

I pondered this. I knew the Bejawi. Some of them had settled near the north end of Widevale, my father’s holdings. I’d been to the settlement once. It was a dirty place, a random tumble of houses without streets, with rubbish and sewage and offal scattered all around it. I hadn’t been impressed. As if my father could hear my thoughts, he said, ‘Sometimes it takes a while for people to adapt to civilization. The learning process can be hard. But in the end it will be of great benefit to them. The Gernian people have a duty to lift the Bejawi folk and help them learn civilized ways.’

Oh, that I understood. Just as struggling with mathematics would one day make me a better soldier. I nodded and continued to ride at his stirrup as we approached the outpost.

The town of Franner’s Bend had become a traders’ rendezvous, where Gernian merchants sold overpriced wares to homesick soldiers and purchased hand-made plainsworked goods and trinkets from the bazaar for the city markets in the west. The military contingent had a barracks and headquarters there which was still the heart of the town but the trade had become the new reason for its existence. Outside the fortified walls a little community had sprung up around the riverboat docks. A lot of common soldiers retired there, eking out their existence with hand-outs from their younger comrades. Once, I suppose, the fort at Franner’s Bend had been of strategic importance. Now it was little more than another backwater on the river. The flags were still raised daily with military precision and a great deal of ceremony and pomp. But, as my father told me on the ride there, duty at Franner’s Bend was a ‘soft post’ now, a plum given to older or incapacitated officers who did not wish to retire to their family homes yet.

Our sole reason for visiting was to determine if my father would win the military contract for sheepskins to use as saddle padding. My family was just venturing into sheep herding at that time, and he wished to assess the market potential for them before investing too heavily in the silly creatures. Much as he detested playing the merchant, he told me, as a new noble he had to establish the investments that would support his estate and allow it to grow. ‘I’ve no wish to hand your brother an empty title when he comes of age. The future Lord Burvelles of the East must have income to support a noble lifestyle. You may think that has nothing to do with you, young Nevare, since as a second son you will go to be a soldier. But when you are an old man, and your soldiering days are through, you will come home to your brother’s estate to retire. You will live out your days at Widevale, and the income of the estate will determine how well your daughters will marry, for it is the duty of a noble first son to provide for his soldier brother’s daughters. It behooves you to know about these things.’

I understood little, then, of what he was telling me. Of late, he talked to me twice as much as he ever had, and I felt I understood only half as much of what he said. He had only recently parted me from my sisters’ company and their gentle play. I missed them tremendously, as I did my mother’s attentions and coddling. The separation had been abrupt, following my father’s discovery that I spent most of my afternoons playing ‘tea-party’ in the garden with Elisi and Yaril, and had even adopted a doll as my own to bring to the nursery festivities. Such play alarmed my father for reasons my eight-year-old mind could not grasp. He had scolded my mother in a muffled ‘discussion’ behind the closed doors of the parlour, and instantly assumed total responsibility for my upbringing. My schoolbook lessons were suspended, pending the arrival of a new tutor he had hired. In the intervening days he kept me at his side for all sorts of tedious errands and constantly lectured me on what my life would be like when I grew up to be an officer in the King’s Cavalla. If I was not with my father, and sometimes even when I was, Corporal Parth supervised me.

The abrupt change had left me both isolated and unsettled. I sensed I had somehow disappointed my father, but was unsure of what I had done. I longed to return to my sisters’ company. I was also ashamed of missing them, for was I not a young man now and on my path to be my father’s soldier son? So he often reminded me, as did fat old Corporal Parth. Parth was what my mother somewhat irritably called a ‘charity hire’. Old, paunchy, and no longer fit for duty, he had come to ask my father’s aid and been hired as an unskilled groundskeeper. He was now the temporary replacement for the nanny I had shared with my sisters. He was supposed to school me in ‘the basics of military bearing and fitness’ each day until my father could find a more qualified instructor. I did not think much of Parth. Nanny Sisi had been more organized and demanded more discipline of me than he did. The slouching old man who had carried his corporal’s rank into retirement with him regarded me as more of a nuisance and a chore than a bright young mind to be shaped and a body to be built with rigor. Often, when he was supposed to be teaching me riding, he spent an hour napping while I practised ‘being a good little sentry and keeping watch’, which meant that I sat in the branches of a shady tree while he slept beneath it. I had not told my father any of that, of course. One thing that Parth had already instructed me in was that he was the commander and I was the soldier, and a good soldier never questioned his orders.

My father was well known at Franner’s Bend. We rode through the town and up to the gates of the fortress. There he was saluted and welcomed without question. I looked curiously about me as we rode past an idle smith’s shop, a warehouse, and a barracks before we reined in our horses before the commander’s headquarters. I gaped up at the grand stone building, three storeys tall, as my father gave Parth his instructions regarding me.

‘Give Nevare a tour of the outpost and explain the layout. Show him the cannon and talk to him about their placement and range. The fortifications here are a classic arrangement of defences. See that he understands what that means.’

If my father had looked back as he ascended the steps, he would have seen how Parth rolled his eyes. My heart sank. It meant that Parth had little intention of complying with my father’s orders, and that I would later be held accountable for what I had not learned, which had happened before. I resolved, however, that it would not happen this time.

I followed him as we walked a short distance down the street. ‘That’s a barracks, where soldiers live,’ he told me. ‘And that’s a canteen, tacked onto the end of it, where soldiers can get a beer and a bit of relaxation when they aren’t on duty.’

The tour of the fort stopped there. The barracks and canteen were constructed of wooden planks, painted green and white. It was a long, low building with an open porch that ran the length of it. Off-duty soldiers idled there, sewing, blacking their boots, or talking and smoking or chewing as they sat on hard benches in the paltry shade. Outside the canteen, another porch offered refuge for a class of men I knew well. Too old to serve or otherwise incapacitated, these men wore a rough mix of military uniform and civilian garb. A lone woman in a faded orange dress slouched at one table, a limp flower behind her ear. She looked very tired. Mustered-out soldiers often approached my father in the hope of work and a place to live. If he thought they had any use at all he usually hired them, much to my lady mother’s dismay. But these men, I immediately knew, my father would have turned away. Their clothes were unkempt, their unshaven faces smudged with dirt. Half a dozen of them loitered on the benches, drinking beer, chewing tobacco and spitting the brownish stuff onto the earth floor. The stink of tobacco juice and spilled beer hung in the air.

As we passed by, Parth glanced longingly into the low windows, and then delightedly hailed an old crony of his, one he evidently hadn’t seen in years. I stood to one side, politely bored, as the two men exchanged reports on their current lives through the window opening, Parth’s friend leaning on the sill to talk to us as we stood in the street. Vev had only recently arrived at the fort with his wife and his two sons, having been mustered out after he injured his back in a fall from his horse. Like many a soldier when his soldiering days were done, he had no resources to fall back on. His wife did a bit of sewing to keep a roof over their heads, but it was rocky going. And what was Parth doing these days? Working for Colonel Burvelle? I saw Vev’s face lighten with interest. He immediately invited Parth to join him in a beer to celebrate their reunion. When I started to follow him up the steps, Parth glared at me. ‘You wait outside for me, Nevare. I won’t be long.’

‘You’re not supposed to leave me alone in town, Corporal Parth,’ I reminded him. I’d heard my father reiterate that carefully on the ride here; young as I was, I was still a bit surprised that Parth had forgotten it already. I waited for him to thank me for the reminder. I considered that my due, for whenever my father had to remind me of a rule I had forgotten, I had to thank him and accept the consequences of my lapse.

Instead Parth scowled at me. ‘You ain’t alone out here, Nevare. I can see you right from the window, and there’s all these old sojers keeping an eye on you. You’ll be fine. Just sit yourself down by the door and wait like I told you.’

‘But I’m supposed to stay with you,’ I objected. My order to stay in Parth’s company was a separate order from his to watch me and show me the fort. He might get in trouble for leaving me alone outside. And I feared my father would do more than rebuke me for not following Parth as I was supposed to.

His drinking companion came up with a solution. ‘My boys Raven and Darda are out there, laddie. They’re down by the corner of the smithy, playing knife toss with the other lads. Whyn’t you go and see how it’s done, and play a little yourself? We won’t be gone long. I just want to talk to your Uncle Parth here about what it takes to find a cushy job like what he’s found for himself, nursie-maiding for old Colonel Burvelle.’

‘Keep a civil tongue in your head when you speak of the boy’s pa in front of him! Do you think he hasn’t got a tongue of his own, to wag on about how you talk? Shut it, Vev, before you put my job on the block.’

‘Well, I didn’t mean anything, as I’m sure Colonel Laddie knew, right, lad?’

I grinned uncertainly. I knew that Vev was needling Parth on purpose, and perhaps mocking my father and me into the bargain. I didn’t understand why. Weren’t they friends? And if Vev were insulting Parth, why didn’t we just walk away like gentlemen, or demand satisfaction of him, as often happened in the tales my eldest sister read aloud to my younger sister when my parents were not about? It was all very confusing, and as there had been much talk over my head of late that I must be taught how men did things now or I should grow up to be effeminate, I hesitated long over what response I should make.

Before I could, Parth gave me a none-too-gentle push in the direction of some older boys lounging at the corner of a warehouse and told me to go and play, for he’d only be a moment or two, and immediately clomped up the steps and vanished into the tavern, so that I was left unchaperoned on the street.

A barracks town can be a rough place. Even at eight I knew that, and so I approached the older boys cautiously. They were, as Vev had said, playing a knife toss game in the alley between the smithy and a warehouse. They were betting half-coppers and pewter bits as each boy took a turn at dropping the knife, point first, into the street. The bets wagered were on whether or not the knife would stick and how close each boy could come to his own foot on the drop without cutting himself. As they were barefoot, the wagers were quite interesting apart from the small coins involved, and a circle of five or so boys had gathered to watch. The youngest of them was still a year or two older than me, and the eldest was in his teens. They were sons of common soldiers, dressed in their father’s cast-offs and as unkempt as stray dogs. In a few more years, they’d sign their papers and whatever regiment took them in would dust them off and shape them into foot soldiers. They knew their own fortunes as well as I knew mine, and seemed very content to spend the last days of their boyhoods playing foolish games in the dusty street.

I had no coins to bet and I was dressed too well to keep company with them, so they made a space in their huddle to let me watch but didn’t speak to me. I learned a few of their names only by listening to them talk to each other. For a time, I was content to watch their odd game, and listen intently to their rough curses and the crude name-calling that accompanied bets lost or won. This was certainly a long way from my sisters’ tea parties, and I recall that I wondered if this were the sort of manly company that of late my father had been insisting I needed.

The sun was warm and the game endless as the bits of coin and other random treasure changed hands over and over. A boy named Carky cut his foot, and hopped and howled for a bit, but soon was back in the game. Raven, Vev’s son, laughed at him and happily pocketed the two pennies and three marbles Carky had bet. I was watching them intently and would scarcely have noticed the arrival of the scout, save that all the other boys suddenly suspended the game and fell silent as he rode past.

I knew he was a scout, for his dress was half-soldier and half-plainsman. He wore dark-green cavalla trousers like a proper trooper, but his shirt was the loose linen of a plainsman, immaculately clean. His hair was not cropped short in a soldier’s cut nor did he wear a proper hat. Instead, his black hair hung loose and long and moved with his white kaffiyeh. A rope of red silk secured his headgear. His arms were bare that summer day, the sleeves rolled to his biceps, and his forearm was circled with tattooed wreaths and trade-bracelets of silver beads and pewter charms and gleaming yellow brass. His horse was a good one, solid black, with long straight legs and jingle charms braided into his mane. I watched him with intent interest. Scouts were a breed apart, it was said. They were ranked as officers, lieutenants usually and frequently were nobly born, but they lived independent lives, outside the regular ranks of the military and often reported directly to the commander of an outpost. They were our first harbingers of any trouble, be it logjams on the river, eroding roads or unrest among the plainspeople.

A girl of twelve or thirteen on a chestnut gelding followed the scout. It was a smaller animal with a finely sculptured brow that spoke of the best nomadic stock. She rode astraddle as no proper Gernian girl would, and by that as much as by her garb I knew her for a mixed blood. It was not uncommon, though still deplored, for Gernian soldiers to take wives from among the plainspeople. It was less common for a scout to stoop so low. I stared at the girl in frank curiosity. My mother often said that the products of cross-unions were abominations before the good god, so I was surprised to see that such a long and ugly-sounding word described such a lovely creature. She was dressed in brightly layered skirts, one orange, one green, one yellow, that blossomed over the horse’s back and covered her knees, but not her calves and feet. She wore soft little boots of antelope skin, and silver charms twinkled on their laces. Loose white trousers showed beneath her bunched skirts. Her shorter kaffiyeh matched her father’s and displayed to advantage the long brown hair that hung down her back in dozens of fine braids. She had a high, round brow and calm grey eyes. Her white blouse bared her neck and arms, displaying the black torc she wore around her throat and a quantity of bracelets, some stacked above her elbows and others jingling at her wrist. She wore the woman’s wealth of her family proudly for all to see. Her naked arms were brown from the sun and as muscled as a boy’s. As she rode, she looked round boldly, very unlike my sisters’ modest manner and downcast eyes when in public.