Полная версия:

Ship of Magic

Ship of Magic

Book One of The Liveship Traders

Robin Hobb

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Voyager 1998

Copyright © Robin Hobb 1998

Cover Layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015. Illustrations © Jackie Morris. Calligraphy by Stephen Raw. Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (background)

Robin Hobb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content or written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in place at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006498858

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007383467

Version: 2018-08-16

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

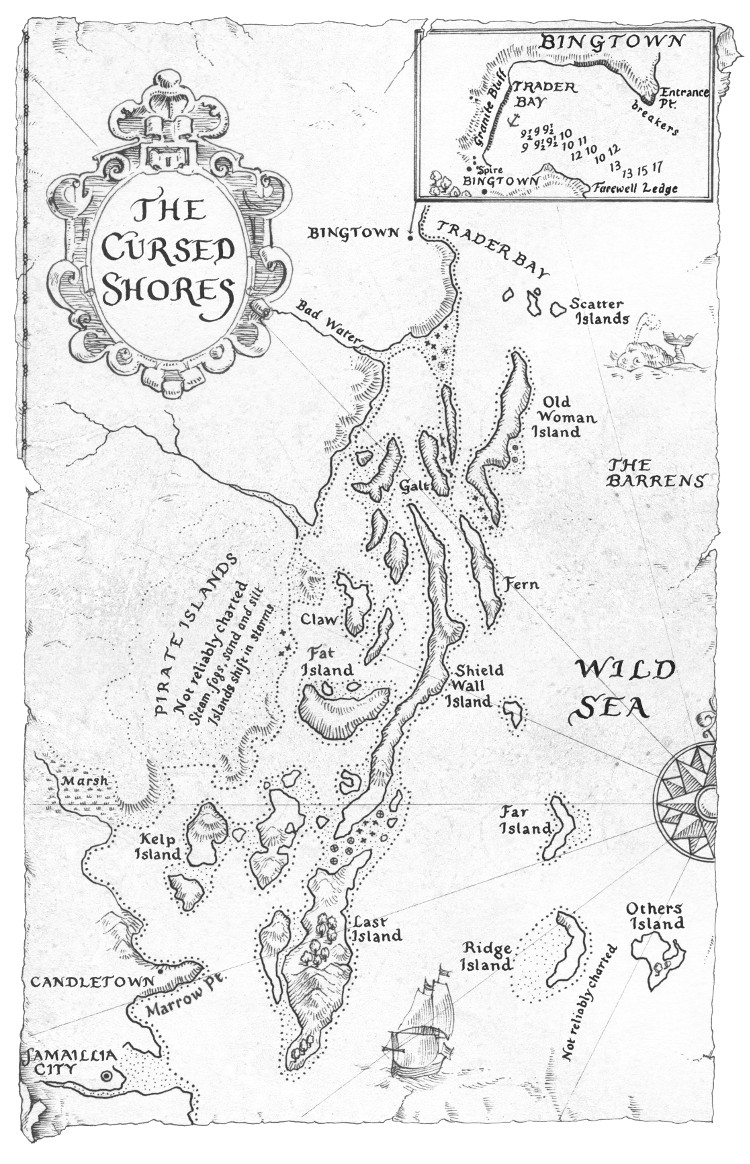

Map

Prologue

1 - OF PRIESTS AND PIRATES

2 - LIVESHIPS

3 - EPHRON VESTRIT

4 - DIVVYTOWN

5 - BINGTOWN

6 - THE QUICKENING OF THE VIVACIA

7 - LOYALTIES

8 - NIGHT CONVERSATIONS

9 - A CHANGE OF FORTUNES

10 - CONFRONTATIONS

11 - CONSEQUENCES AND REFLECTIONS

12 - OF DERELICTS AND SLAVESHIPS

13 - TRANSITIONS

14 - FAMILY MATTERS

15 - NEGOTIATIONS

AUTUMN

16 - NEW ROLES

17 - KENNIT'S WHORE

18 - MALTA

19 - TESTIMONIES

WINTER

20 - CRIMPERS

21 - VISITORS

22 - PLOTS AND PERILS

23 - JAMAILLIA SLAVERS

24 - RAIN WILD TRADERS

25 - CANDLETOWN

26 - GIFTS

27 - PRISONERS

28 - VICISSITUDES

29 - DREAMS AND REALITY

30 - DEFIANCE AND ALLIANCE

31 - SHIPS AND SERPENTS

32 - STORM

33 - DAY OF RECKONING

34 - RESTORATIONS

35 - PIRATES AND CAPTIVES

36 - SHE WHO REMEMBERS

Keep Reading

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

This one is for

The Devil’s Paw The Totem The E J Bruce The Free Lunch The Labrador (Scales! Scales!) The (aptly named) Massacre Bay The Faithful (Gummi Bears Ahoy!) The Entrance Point The Cape St John The American Patriot (and Cap’n Wookie) The Lesbian Warmonger The Anita J and the Marcy J The Tarpon The Capelin The Dolphin The (not very) Good News Bay And even the Chicken Little But especially for Rain Lady, wherever she may be now.

Map

Prologue

MAULKIN ABRUPTLY HEAVED HIMSELF out of his wallow with a wild thrash that left the atmosphere hanging thick with particles. Shreds of his shed skin floated with the sand and mud like the dangling remnants of dreams when one awakes. He moved his long sinuous body through a lazy loop, rubbing against himself to rub off the last scraps of outgrown hide. As the bottom muck started to once more settle, he gazed about at the two dozen other serpents who lay basking in the pleasantly scratchy dirt. He shook his great maned head and then stretched the vast muscle of his length. ‘Time,’ he bugled in his deep-throated voice. ‘The time has come.’

They all looked up at him from the sea-bottom, their great eyes of green and gold and copper unwinking. Shreever spoke for them all when she asked, ‘Why? The water is warm, the feeding easy. In a hundred years, winter has never come here. Why must we leave now?’

Maulkin performed another lazy twining. His newly bared scales shone brilliantly in the filtered blue sunlight. His preening burnished the golden false-eyes that ran his full length, declaring him one of those with ancient sight. Maulkin could recall things, things from the time before all this time. His perceptions were not clear, nor always consistent. Like many of those caught twixt times, with knowledge of both lives, he was often unfocused and incoherent. He shook his mane until stunning poison made a pale cloud about his face. He gulped his own toxin in, breathed it out through his gills in a show of truth-vow. ‘Because it is time now!’ he said urgently. He sped suddenly away from them all, shooting up to the surface, rising straighter and faster than bubbles. Far above them all he broke the ceiling and leapt out briefly into the great Lack before he dived again. He circled them in frantic circles, wordless in his urgency.

‘Some of the other tangles have already gone,’ Shreever said thoughtfully. ‘Not all of them, not even most. But enough to notice they are missing when we rise into the Lack to sing. Perhaps it is time.’

Sessurea settled deeper into the mud. ‘And perhaps it is not,’ he said lazily. ‘I think we should wait until Aubren’s tangle goes. Aubren is… steadier than Maulkin.’

Beside him, Shreever abruptly heaved herself out of the muck. The gleaming scarlet of her new skin was startling. Rags of maroon still hung from her. She nipped a great hank of it free and gulped it down before she spoke. ‘Perhaps you should join Aubren’s tangle, if you misdoubt Maulkin’s words. I, for one, will follow him north. Better to go too soon, than too late. Better to go early, perhaps, than to come with scores of other tangles and have to vie for feeding.’ She moved lithely through a knot made of her own body, rubbing the last fragments of old hide free. She shook her own mane, then threw back her head. Her shriller trumpeting disturbed the water. ‘I come, Maulkin! I follow you!’ She moved up to join their still circling leader in his twining dance overhead.

One at a time, the other great serpents heaved their long bodies free of clinging mud and outgrown skin. All, even Sessurea, rose from the depths to circle in the warm water just below the ceiling of the Plenty, joining in the tangle’s dance. They would go north, back to the waters from whence they had come, in the long ago time that so few now remembered.

1 OF PRIESTS AND PIRATES

KENNIT WALKED THE TIDELINE, heedless of the salt waves that washed around his boots as it licked the sandy beach clean of his tracks. He kept his eyes on the straggling line of seaweed, shells and snags of driftwood that marked the water’s highest reach. The tide was just turning now, the waves falling ever shorter in their pleading grasp upon the land. As the saltwater retreated down the black sand, it would bare the worn molars of shale and tangles of kelp that now hid beneath the waves.

On the other side of Others’ Island, his two-masted ship was anchored in Deception Cove. He had brought the Marietta in to anchor there as the morning winds had blown the last of the storm clean of the sky. The tide had still been rising then, the fanged rocks of the notorious cove grudgingly receding beneath frothy green lace. The ship’s gig had scraped over and between the barnacled rocks to put him and Gankis ashore on a tiny crescent of black sand beach which disappeared completely when storm winds drove the waves up past the high tide marks. Above, slate cliffs loomed and evergreens so dark they were nearly black leaned precariously out in defiance of the prevailing winds. Even to Kennit’s iron nerves, it was like stepping into some creature’s half-open mouth.

They’d left Opal, the ship’s boy, with the gig to protect it from the bizarre mishaps that so often befell unguarded craft in Deception Cove. Much to the boy’s unease, Kennit had commanded Gankis to come with him, leaving boy and boat alone. At Kennit’s last sight, the boy had been perched in the beached hull. His eyes had alternated between fearful glances over his shoulder at the forested cliff-tops and staring anxiously out to where the Marietta strained against her anchors, yearning to join the racing current that swept past the mouth of the cove.

The hazards of visiting this island were legendary. It was not just the hostility of even the ‘best’ anchorage on the island, nor the odd accidents known to befall ships and visitors. The whole of the island was enshrouded in the peculiar magic of the Others. Kennit had felt it tugging at him as he followed the path that led from Deception Cove to the Treasure Beach. For a path seldom used, its black gravel was miraculously clean of fallen leaves or intruding plant life. About them the trees dripped the second-hand rain of last night’s storm onto fern fronds already burdened with crystal drops. The air was cool and alive. Brightly-hued flowers, always growing at least a man’s length from the path, challenged the dimness of the shaded forest floor. Their scents drifted alluringly on the morning air as if beckoning the men to leave off their quest and explore their world. Less wholesome in appearance were the orange fungi that stair-stepped up the trunks of many of the trees. The shocking brilliance of their colour spoke to Kennit of parasitic hungers. A spider’s web, hung like the ferns with fine droplets of shining water, stretched across their path, forcing them to duck under it. The spider that sat at the edges of its strands was as orange as the fungi, and nearly as big as a baby’s fist. A green tree-frog was enmeshed and struggling in the web’s sticky strands, but the spider appeared disinterested. Gankis made a small sound of dismay as he crouched to go beneath it.

This path led right through the midst of the Others’ realm. Here was where the nebulous boundaries of their territory could be crossed by a man, did he dare to leave the well-marked path allotted to humans and step off into the forest to seek them. In ancient times, so tale told, heroes came here, not to follow the path but to leave it deliberately, to beard the Others in their dens, and seek the wisdom of their cave-imprisoned goddess, or demand gifts such as cloaks of invisibility and swords that ran with flames and could shear through any shield. Bards that had dared to come this way had returned to their homelands with voices that could shatter a man’s ears with their power, or melt the heart of any listener with their skill. All knew the ancient tale of Kaven Ravenlock, who visited the Others for half a hundred years and returned as if but a day had passed for him, but with hair the colour of gold and eyes like red coals and true songs that told of the future in twisted rhymes. Kennit snorted softly to himself. All knew such ancient tales, but if any man had ventured to leave this path in Kennit’s lifetime, he had told no other man about it. Perhaps he had never returned to brag of it. The pirate dismissed it from his mind. He had not come to the island to leave the path, but to follow it to its very end. And all knew what waited there as well.

Kennit had followed the gravel path that snaked through the forested hills of the island’s interior until its winding descent spilled them out onto a coarsely-grassed tableland that framed the wide curve of an open beach. This was the opposite shore of the tiny island. Legend foretold that any ship that anchored here had only the netherworld as its next port of call. Kennit had found no record of any ship that had dared challenge that rumour. If any had, its boldness had gone to hell with it.

The sky was a clean brisk blue scoured clean of clouds by last night’s storm. The long curve of the rock-and-sand beach was broken only by a freshwater stream that cut its way through the high grassy bank backing the beach. The stream meandered over the sand to be engulfed in the sea. In the distance, higher cliffs of black shale rose, enclosing the far end of the crescent beach. One toothy tower of shale stood independent of the island, jutting out crookedly from the island with a small stretch of beach between it and its mother-cliff. The gap in the cliff framed a blue slice of sky and restless sea.

‘It was a fair bit of wind and surf we had last night, sir. Some folk say that the best place to walk the Treasure Beach is on the grassy dunes up there… they say that in a good bit of storm, the waves throw things up there, fragile things you might expect to be smashed to bits on the rocks and such, but they land on the sedge up there, just as gentle as you please.’ Gankis panted out the words as he trotted at Kennit’s heels. He had to stretch his stride to keep up with the tall pirate. ‘An uncle of mine — that is to say, actually he was married to my aunt, to my mother’s sister — he said he knew a man found a little wooden box up there, shiny black and all painted with flowers. Inside was a little glass statue of a woman with butterfly’s wings. But not transparent glass, no, the colours of the wings were swirled right in the glass they were.’ Gankis stopped in his account and half-stooped his head as he glanced cautiously at his master. ‘Would you want to know what the Other said it meant?’ he inquired carefully.

Kennit paused to nudge the toe of his boot against a wrinkle in the wet sand. A glint of gold rewarded him. He bent casually to hook his finger under a fine gold chain. As he drew it up, a locket popped out of its sandy grave. He wiped the locket down the front of his fine linen trousers, and then nimbly worked the tiny catch. The gold halves popped open. Saltwater had penetrated the edges of the locket, but the portrait of a young woman still smiled up at him, her eyes both merry and shyly rebuking. Kennit merely grunted at his find and put it in the pocket of his brocaded waistcoat.

‘Cap’n, you know they won’t let you keep that. No one keeps anything from the Treasure Beach,’ Gankis pointed out gingerly.

‘Don’t they?’ Kennit queried in return. He put a twist of amusement in his voice, to watch Gankis puzzle over whether it was self-mockery or a threat. Gankis shifted his weight surreptitiously, to put his face out of reach of his captain’s fist.

‘S’what they all say, sir,’ he replied hesitantly. ‘That no one takes home what they find on the Treasure Beach. I know for sure my uncle’s friend didn’t. After the Other looked at what he’d found and told his fortune from it, he followed the Other down the beach to this rock cliff. Probably that one.’ Gankis lifted an arm to point at the distant shale cliffs. ‘And in the face of it there were thousands of little holes, little what-you-call-’ems…’

‘Alcoves,’ Kennit supplied in an almost dreamy voice. ‘I call them alcoves, Gankis. As would you, if you could speak your own mother tongue.’

‘Yessir. Alcoves. And in each was a treasure, ’cept for those that were empty. And the Other let him walk along the cliff wall and look at all the treasures, and there was stuff there such as he’d never even imagined. China teacups done all in fancy rosebuds and gold wine cups rimmed with jewels and little wooden toys all painted bright and, oh, a hundred things such as you can’t imagine, each in an alcove. Sir. And then he found an alcove the right size and shape, and he put the butterfly lady in it. He told my uncle that nothing ever felt quite so right to him as setting that little treasure into that nook. And then he left it there, and left the island and went home.’

Kennit cleared his throat. The single noise conveyed more of contempt and disdain than most men could have fitted into an entire stream of abuse. Gankis looked aside and down from it. ‘It was him that said it, sir, not me.’ He tugged at the waist of his worn trousers. Almost reluctantly he added, ‘The man is a bit in the dream world. Gives a seventh of all that comes his way to Sa’s temple, and both his eldest children besides. Such a man don’t think as we do, sir.’

‘When you think at all, Gankis,’ the captain concluded for him. He lifted his pale eyes to look far up the tide line, squinting slightly as the morning sun dazzled off the moving waves. ‘Take yourself up to your sedgy cliffs, Gankis, and walk along them. Bring me whatever you find there.’

‘Yessir.’ The older pirate trudged away. He gave one rueful backward glance at his young captain. Then he clambered agilely up the short bank to the deeply-grassed tableland that fronted on the beach. He began to walk a parallel course, his eyes scanning the bank ahead of him. Almost immediately, he spotted something. He sprinted toward it, then lifted an object that flashed in the morning sunlight. He raised it up to the light and gazed at it, his seamed face lit with awe. ‘Sir, sir, you should see what I’ve found!’

‘I might be able to, did you bring it here to me as you were commanded,’ Kennit observed irritably.

Like a dog called to heel, Gankis made his way back to the captain. His brown eyes shone with a youthful sparkle, and he clutched the treasure in both hands as he leapt nimbly down the man-height drop to the beach. His low shoes kicked up sand as he ran. A brief frown creased Kennit’s brow as he watched Gankis advancing towards him. Although the old sailor was prone to fawn on him, he was no more inclined to share booty than any other man of his trade. Kennit had not truly expected Gankis willingly to bring to him anything he found on the grassy bank; in fact he had been rather anticipating divesting the man of his trove at the end of their stroll. To have Gankis hastening toward him, his face beaming as if he were a country yokel bringing his beloved milkmaid a posy, was positively unsettling.

Nevertheless Kennit retained his customary sardonic smile, not allowing his face to betray his thoughts. It was a carefully rehearsed posture that suggested the languid grace of a hunting cat. It was not just that his greater height allowed him to look down on the seaman. By capturing his face in a pose of amusement, he suggested to his followers that they were incapable of surprising him. He wished his crew to believe that he could anticipate not only their every move, but their thoughts, too. A crew that believed that of their captain was less likely to become mutinous; and if they did, no one would wish to be the first to act.

And so he kept his poise as the man raced across the sand to him. Moreover, he did not immediately snatch the treasure away from him, but allowed Gankis to hold it out to him while he gazed down at it in amusement.

From the instant he saw it, it took all of Kennit’s control not to snatch at it. Never had he seen such a cunningly wrought bauble. It was a bubble of glass, an absolutely perfect sphere. The surface was not marred with so much as a scratch. The glass itself had a very faint blue cast to it, but the tint did not obscure the wonder within. Three tiny figurines, garbed in motley with painted faces, were fixed to a tiny stage and somehow linked to one another so that when Gankis shifted the ball in his hands, it sent them off into a series of actions. One pirouetted on his toes, while the next did a series of flips over a bar. The third bobbed his head in time to their actions, as if all three heard and responded to a merry tune trapped inside the ball with them.

Kennit allowed Gankis to demonstrate it for him twice. Then, without a word, he extended a long-fingered hand towards him gracefully, and the sailor set the treasure in his palm. Kennit held his bemused smile firmly as he first lifted the ball to the sunlight, and then set the tumblers within to dancing for himself. The ball did not quite fill his hand. ‘A child’s plaything,’ he surmised loftily.

‘If the child were the richest prince in the world,’ Gankis dared to observe. ‘It’s too fragile a thing to give a kid to play with, sir. All it would take would be dropping it once…’

‘Yet it seems to have survived bobbing about in the waves of a storm, and then being flung up on a beach,’ Kennit pointed out with measured good nature.

‘That’s true, sir, that’s true, but then this is the Treasure Beach. Almost everything cast up here is whole, from what I’ve heard tell. It’s part of the magic of this place.’

‘Magic’ Kennit permitted himself a slightly wider smile as he placed the orb in the roomy pocket of his indigo jacket. ‘So you believe it is magic that sweeps such trinkets up on this shore, do you?’

‘What else, captain? By all rights, that should have been smashed to bits, or at least scoured by the sands. Yet it looks as if it just come out of a jeweller’s shop.’

Kennit shook his head sadly. ‘Magic? No, Gankis, no more magic than the rip-tides in the Orte Shallows, or the Spice Current that speeds sailing ships on their journeys to the islands and taunts them all the way back. It’s but a trick of wind and current and tides. No more than that. The same trick that promises that any ship that tries to anchor off this side of the island will find herself beached and broken before the next tide.’

‘Yessir,’ Gankis agreed dutifully, but without conviction. His traitorous eyes strayed to the pocket where Captain Kennit had stowed the glass ball. Kennit’s smile might have deepened fractionally.

‘Well? Don’t loiter here. Get back up there and walk the bank and see what else you find.’

‘Yessir,’ Gankis conceded, and with one final regretful glance at the pocket, the older man turned and hastened back to the bank. Kennit slipped his hand into his pocket and caressed the smooth cold glass there. He resumed his stroll down the beach. Overhead gulls followed his example, sliding slowly down the wind as they searched the retreating waves for titbits. He did not hasten, but kept in mind that on the other side of the island his ship was awaiting him in treacherous waters. He’d walk the whole length of the beach, as tradition decreed, but he had no intention of lingering after he had heard the sooth-saying of an Other. Nor did he have any intention of leaving whatever treasure he found. A true smile tugged at the corner of his mouth.

As he strolled, he took his hand from his pocket and absently touched his opposite wrist. Concealed by the lacy cuff of his white silk shirt was a fine double thong of black leather. It bound a small wooden trinket tightly to his wrist. The ornament was a carved face, pierced at the brow and lower jaw so the face would be snugged firmly against his wrist, exactly over his pulse point. At one time, the face had been painted black, but most of that was worn away now. The features still stood out distinctly; a tiny mocking face, carved with exquisite care. Its visage was twin to his own. It had cost him an inordinate amount of coin to commission it. Not everyone who could carve wizardwood would, even if they had the balls to steal some.