Полная версия:

Fool’s Quest

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Robin Hobb 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration © Jackie Morris; lettering by Stephen Raw.

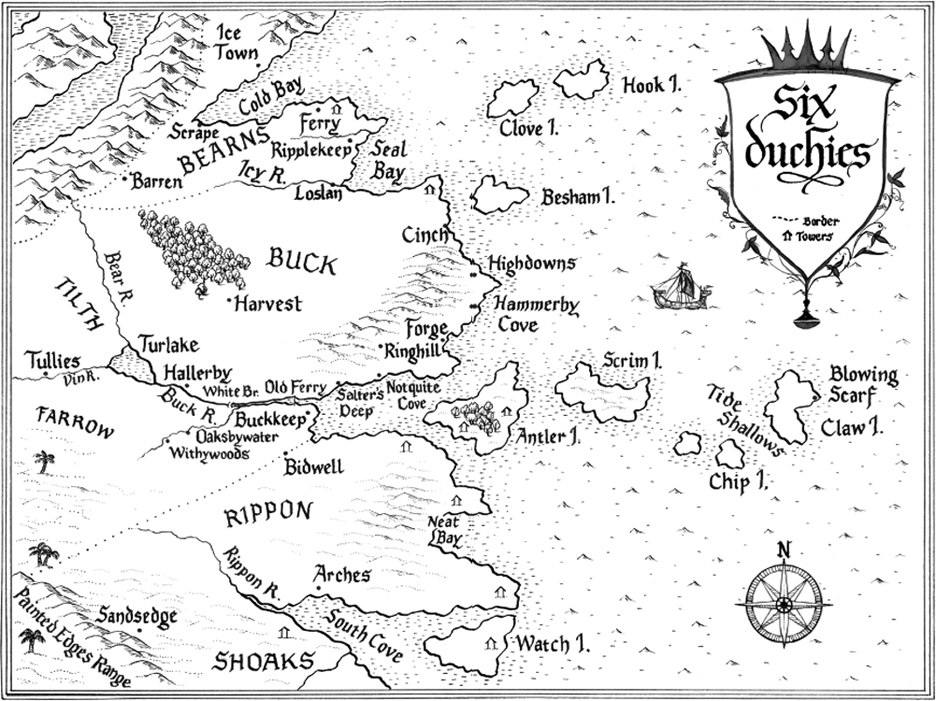

Map copyright © Nicolette Caven 2015

Robin Hobb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007444212

Ebook Edition © August 2015 ISBN: 9780007444236

Version: 2018-09-24

Dedication

To Rudyard. Still my Best Beloved

after all these years

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map

Chapter One: Winterfest Eve at Buckkeep

Chapter Two: Lord Feldspar

Chapter Three: The Taking of Bee

Chapter Four: The Fool’s Tale

Chapter Five: An Exchange of Substance

Chapter Six: The Witted

Chapter Seven: Secrets and a Crow

Chapter Eight: Farseers

Chapter Nine: The Crown

Chapter Ten: Tidings

Chapter Eleven: Withywoods

Chapter Twelve: The Shaysim

Chapter Thirteen: Chade’s Secret

Chapter Fourteen: Elfbark

Chapter Fifteen: Surprises

Chapter Sixteen: The Journey

Chapter Seventeen: Blood

Chapter Eighteen: The Changer

Chapter Nineteen: The Strategy

Chapter Twenty: Marking Time

Chapter Twenty-One: Vindeliar

Chapter Twenty-Two: Confrontations

Chapter Twenty-Three: Bonds and Ties

Chapter Twenty-Four: Parting Ways

Chapter Twenty-Five: Red Snow

Chapter Twenty-Six: A Glove

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Aftermath

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Repercussions

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Family

Chapter Thirty: Prince FitzChivalry

Chapter Thirty-One: Loose Ends

Chapter Thirty-Two: Travellers

Chapter Thirty-Three: Departure

Chapter Thirty-Four: Dragons

Chapter Thirty-Five: Kelsingra

Chapter Thirty-Six: An Elderling Welcome

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Heroes and Thieves

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Emergence

Keep Reading

About the Author

Also by Robin Hobb

About the Publisher

ONE

Winterfest Eve at Buckkeep

I am warm and safe in the den, with my two siblings. They are both heartier and stronger than I am. Born last, I am smallest of all. My eyes were slow to open, and I have been the least adventurous of the cubs. Both my brother and my sister have dared, more than once, to follow my mother to the mouth of the den dug deep in the undercut bank of the river. Each time, she has snarled and snapped at them, driving them back. She leaves us alone when she goes out to hunt. There should be a wolf to watch over us, a younger member of the pack who remains with us. But she is all that is left of the pack, and so she must go out to hunt alone and we must stay where she leaves us.

There is a day when she shakes free of us, long before we have had enough of her milk. She leaves us, going to the hunt, leaving the den as evening starts to creep across the land. We hear from her a single yelp. That is all.

My brother, the largest of us, is filled with both fear and curiosity. He whines loudly, trying to call her back to us, but there is no response. He starts to go to the entrance of the den and my sister follows him, but in a moment they come scrabbling back to hunker down in fear beside me. There are strange smells right outside the den, bad smells, blood and creatures unknown to us. As we hide and whimper, the blood-smell grows stronger. We do the only thing we know to do. We hunch and huddle against the far back wall of the den.

We hear sounds. Something that is not paws digs at the mouth of our den. It sounds like a large tooth biting into the earth, biting and tearing, biting and tearing. We hunch even deeper and my brother’s hackles rise. We hear sounds and we know there is more than one creature outside the den. The blood-smell thickens and is mingled with the smell of our mother. The digging noises go on.

Then there is another smell. In years to come I will know what it is, but in the dream it is not smoke. It is a smell that none of us understands, and it comes in driven wafts into the den. We cry, for it stings our eyes and sucks the breath from our lungs. The den becomes hot and airless and finally my brother crawls toward the den opening. We hear his wild yelping, and how it continues, and then there is the stink of fear-piss. My sister huddles behind me, getting smaller and stiller. And then she is not breathing or hiding any more. She is dead.

I sink down, my paws over my nose, my eyes blinded by the smoke. The digging noises go on and then something seizes me. I yelp and struggle, but it holds tight to my front leg and drags me from the den.

My mother is a hide and a bloody red carcass thrown to one side. My brother huddles in terror in the bottom of a cage in the back of a two-wheeled cart. They fling me in beside him and then drag out my sister’s body. They are angry she is dead, and they kick her about as if somehow their anger can make her feel pain now. Then, complaining of the cold and oncoming dark, they skin her and add her small hide to my mother’s. The two men climb onto the cart and whip up their mule, already speculating at the prices that wolf cubs will bring from the dog-fighting markets. My mother’s and sister’s bloody hides fill my nose with the stench of death.

It is only the beginning of a torment that lasts for a lifetime. Some days we are fed and sometimes not. We are given no shelter from the rain. The only warmth is that of our own bodies as we huddle together. My brother, thin with worms, dies in a pit, thrown in to whet the ferocity of the fighting dogs. And then I am alone. They feed me on offal and scraps or nothing at all. My feet become sore from pawing at the cage, my claws split and my muscles ache from confinement. They beat me and poke me to provoke me to hurl myself against bars I cannot break. They speak outside my cage of their plans to sell me for the fighting-pits. I hear the words but I do not understand them.

I did understand the words. I spasmed awake, and for a moment everything was wrong, everything was foreign. I was huddled in a ball, shuddering, and my fur had been stripped away to bare skin and my legs were bent at the wrong angles and confined by something. My senses were as deadened as if I were wadded in a sack. All around me were the smells of those hated creatures. I bared my teeth and, snarling, fought my way out of my bonds.

Even after I landed on the floor, the blanket trailing after me and my body asserting that I was, indeed, one of those hated humans, I stared in confusion around the dark room. It felt as if it should be morning, but the floor beneath me was not the smooth oaken plank of my bedchamber, nor did the room smell as if it belonged to me. I came slowly to my feet, my eyes striving to adjust. My straining vision caught the blinking of tiny red eyes, and then translated them to the dying embers of a fire. In a fireplace.

As I felt my way across the chamber, the world fell into place around me. Chade’s old rooms at Buckkeep Castle emerged from the blackness when I poked at the embers and added a few sticks of wood. Numbly, I found fresh candles and kindled them, awakening the room to its perpetual twilight. I looked around, letting my life catch up with me. I judged that the night had passed and that outside the thick and windowless walls, day had dawned. The dire events of the previous day – how I had nearly killed the Fool, left my child in the charge of folk I did not fully trust, and then dangerously drained Riddle of Skill-strength to bring the Fool to Buckkeep – rushed over me in a sweeping tide. They met the engulfing memories of all the evenings and nights I’d spent in this windowless chamber, learning the skills and secrets of being the king’s assassin. When finally the sticks caught flame, enriching the thin candlelight in the room, I felt as if I had made a long journey to return to myself. The wolf’s dream of his horrific captivity was fading. I wondered briefly why it had come back in such intensity, and then let it go. Nighteyes, my wolf, my brother, was long gone from this world. The echoes of him lived on in my mind, my heart and my memories, but in what I faced now, he was no longer at my back. I stood alone.

Except for the Fool. My friend had returned to me. Battered, beaten, and possibly not in his right mind, but he was at my side again. I held a candle high and ventured back to the bed we had shared.

The Fool was still deeply asleep. He looked terrible. The marks of torture were written on his scarred face, hardship and starvation had chapped and chafed his skin and thinned his hair to broken straw. Even so, he looked better than when first I had seen him. He was clean, and fed, and warm. And his even breathing was that of a man given a fresh infusion of strength. I wished I could say I had given it to him. All unwitting, I had stolen strength from Riddle and passed it to my friend during our Skill-passage through the standing stones. I regretted how I had abused Riddle in my ignorance but I could not deny the relief I felt to hear the Fool’s steady breathing. Last night he had had the strength to talk with me, and he had walked a bit, bathed himself and eaten a meal. That was far more than I would have expected of the battered beggar I had first seen.

But borrowed strength is not true strength. The hasty Skill-healing I’d practised on him had robbed him of his scanty physical reserves, and the vitality I had stolen from Riddle and given to him could not long sustain him. I hoped the food and rest he had taken yesterday had begun to rebuild his body. I watched him sleeping so deeply and dared to hope he would live. Moving softly, I picked up the bedding I had dragged to the floor in my fall and arranged it warmly around him.

He was so changed. He had been a man who loved beauty in all its forms. His tailored garments, the ornaments in his chambers, the hangings for his bed and windows, even the tie that had held back his immaculately groomed hair had all been chosen with harmony and fashion in mind. But that man was gone. He had come back to me as a ragbag scarecrow of a man. The flesh of his face had fallen to skin-coated bones. Battered, blinded, wearing the scars of torture, the Fool had been so transformed by hardship that I hadn’t recognized him. Gone was the lithe and limber jester with the mocking smile. Gone, too, elegant Lord Golden with his fine clothes and aristocratic ways. I was left with this cadaverous wretch.

His blind eyes were closed. His mouth was a finger’s width ajar. His breath hissed in and out. ‘Fool?’ I said and jogged his shoulder cautiously. His only response was a slight hitch in his breathing. Then he sighed out, as if giving up on pain and fear, before resuming the even respiration of deep sleep.

He had fled torture and travelled through hardship and privation to meet me. His health was broken and he feared deadly pursuit. I could not grasp how he had managed it, broken and blind. But he’d done it, and for one purpose. Last night, before he had surrendered to unconsciousness, he had asked me to kill for him. He wanted us to return to Clerres, to his old school and to the people who had tormented him. And as a special favour, he had asked that I use my old assassin’s skills to kill them all.

He knew that I’d left that part of my life behind me. I was a different man, a respectable man, a steward of my daughter’s home, the father of a little girl. Assassin no more. I’d left killing behind. It had been years since I’d been lean, the muscles of my arms as hard as the heart of a killer. I was a country gentleman now. We had both changed so much.

I could still recall the mocking smile and flashing glance that had once been his, charming and enraging at once. He had changed, but I was confident I still knew him in the important ways, the one that went beyond trivial facts such as where he had been born or who his parents had been. I’d known him since we were young. A sour smile twisted my mouth. Not since we were children. In some ways I doubted that either of us had ever truly been children. But the long years of deep friendship were a foundation I could not doubt. I knew his character. I knew his loyalty and dedication. I knew more of his secrets than anyone, and I had guarded those secrets as carefully as if they were my own. I’d seen him in despair, and incapacitated with terror. I’d seen him broken with pain and I’d seen him drunk to maudlin. And beyond that, I’d seen him dead, and been him dead, and walked his body back to life and called his spirit back to inhabit that body.

So I knew him. From the bones out.

Or so I had thought.

I took a deep breath and sighed it out, but there was no relief from the tension I felt. I was like a child, terrified of looking out into the darkness for fear of what I might see. I was denying what I knew was true. I did know the Fool, from his bones out. And I knew that the Fool would do whatever he thought he must do in order to set the world in its best track. He had let me tread the razor’s edge between death and life, had expected me to endure pain, hardship and loss. He had surrendered himself to a tortured death he had believed was inevitable. All for the sake of his vision of the future.

So if he believed that someone must be killed, and he could not kill that person himself, he would ask it of me. And he would freight the request with those terrible words. ‘For me.’

I turned away from him. Yes. He would ask that of me. The very last thing I ever wanted to do again. And I would say yes. Because I could not look at him, broken and in anguish, and not feel a sea-surge of anger and hatred. No one, no one could be allowed to hurt him as badly as they’d hurt him and continue to live. Anyone so lacking in empathy that they could systematically torment and physically degrade another should not be suffered to live. Monsters had done this to him. Regardless of how human they might appear, this evidence of their work spoke the truth. They needed to be killed. And I should do it.

I wanted to do it. The longer I looked at him, the more I wanted to go and kill, not quickly and quietly, but messily and noisily. I wanted the people who had done this to him to know they were dying and to know why. I wanted them to have time to regret what they’d done.

But I couldn’t. And that tore at me.

I would have to say no. Because as much as I loved the Fool, as deep as our friendship went, as furiously hot as my hatred burned, Bee had first rights to my protection. And dedication. Already I had violated that, leaving her to the care of others while I rescued my friend. My little girl was all I had left now of my wife Molly. Bee was my last chance to be a good father, and I hadn’t been doing very well at it lately. Years ago, I’d failed my older daughter Nettle. I’d left her to think another man was her father, given her over to someone else to raise. Nettle already doubted my ability to care for Bee. Already she had spoken of taking Bee out of my care and bringing her here, to Buckkeep, where she could oversee her upbringing.

I could not allow that. Bee was too small and too strange to survive among palace politics. I had to keep her safe, with me, at Withywoods, in a quiet and secure rural manor, where she might grow as slowly and be as odd as she wished. And as wonderful. So although I had left her to save the Fool, it was only this once and only for a short time. I’d go back to her. Perhaps, I consoled myself, if the Fool recovered enough, I could take him with me. Take him to the quiet and comfort of Withywoods, let him find healing and peace there. He was in no condition to make a journey back to Clerres, let alone aid me in killing whoever had done this to him. Vengeance, I knew, could be delayed, but the life of a growing child could not. I had one chance to be Bee’s father and that time was now. At any time, I could be an assassin for the Fool. So for now, the best I could offer him was peace and healing. Yes. Those things would have to come first.

For a time, I quietly wandered the assassin’s lair where I had spent many happy childhood hours. The clutter of an old man had given way to the tidy organizing skills of Lady Rosemary. She presided over these chambers now. They were cleaner and more pleasant, but somehow I missed Chade’s random projects and jumbles of scrolls and medicines. The shelves that had once held everything from a snake’s skeleton to a piece of bone turned to stone now displayed a tidy array of stoppered bottles and pots.

They were neatly labelled in a lady’s elegant hand. Here was carryme and elfbark, valerian and wolfsbane, mint and beargrease, sumac and foxglove, cindin and Tilth smoke. One pot was labelled OutIslander elfbark, probably to distinguish it from the far milder Six Duchies herb. A glass vial held a dark red mixture that swirled uneasily at the slightest touch. There were threads of silver in it that did not mingle with the red, yet did not float like oil on water. I’d never seen such a mixture. It had no label and I put it back carefully in the wooden rack that kept it upright. Some things were best left alone. I had no idea what karuge root was, nor bloodrun, but both had tiny red skulls inked next to their names.

On the shelf below were mortars and pestles, knives for chopping, sieves for straining and several small heavy pots for rendering. There were stained metal spoons, neatly racked. Below them was a row of small clay pots that puzzled me at first. They were no bigger than my fist, glazed a shiny brown, as were their tight-fitting lids. They were sealed shut with tar, except for a hole in the middle of each lid. A tail of twisted waxed linen emerged from each hole. I hefted one cautiously and then understood. Chade had told me that his experiment with his exploding powder had been progressing. These represented his most recent advance in how to kill people. I set the pot back carefully. The tools of the killing trade that I had forsaken stood in rows like faithful troops. I sighed, but not out of regret, and turned away from them. The Fool slept on.

I tidied the dishes from our late night repast onto a tray and otherwise brought the chamber to rights. The tub of bathwater, now cold and grey, remained, as did the repulsively soiled undergarment the Fool had worn. I did not even dare to burn it on the hearth for fear of the stench it would emit. I did not feel disgust, only pity. My own clothing from the day before was still covered in blood, both from a dog and the Fool. I told myself it was not all that noticeable on the dark fabric. Then, thinking again, I went to investigate the old carved wardrobe that had always stood beside the bed. At one time, it had held only Chade’s work robes, all of them of serviceable grey wool and most of them stained or scorched from his endless experiments. Only two work robes hung there now, both dyed blue and too small for me. There was also, to my surprise, a woman’s night robe and two simple shifts. A pair of black leggings that would have been laughably short on me. Ah. These were Lady Rosemary’s things. Nothing here for me.

It disturbed me to slip quietly from the rooms and leave the Fool sleeping, but I had errands to carry out. I suspected that someone would be sent in to do the cleaning and to supply the room afresh, and I did not like to leave him there unconscious and vulnerable. But at that point, I knew I owed Chade my trust. He had provided all for us the previous evening, despite his pressing duties.

The Six Duchies and the Mountain Kingdom sought to negotiate alliances, and to that end powerful representatives had been invited to come to Buckkeep Castle for the week of Winterfest. Yet even in the middle of an evening of feasting, music and dancing, not only Chade but King Dutiful and his mother, Lady Kettricken, had found time to slip away and greet me and the Fool, and Chade had still found a way to have this chamber well supplied with all we needed. He would not be careless of my friend. Whoever he sent to this chamber would be discreet.

Chade. I took a breath and reached for him with the Skill-magic. Our minds brushed. Chade? The Fool is asleep and I’ve some errands that I’d like—

Yes, yes, fine. Not now, Fitz. We’re discussing the Kelsingra situation. If they are not willing to control their dragons, we may have to form an alliance to deal with the creatures. I’ve made provisions for you and your guest. There is coin in a purse on the blue shelf if you need it. But now I must put my full attention to this. Bingtown claims that Kelsingra may actually be seeking an alliance with the Duchess of Chalced!

Oh. I withdrew. Abruptly, I felt like a child who had interrupted the adults discussing important things. Dragons. An alliance against dragons. Alliance with whom? Bingtown? And what could anyone hope to do against dragons save bribe them with enough meat to stupefy them? Would not befriending the arrogant carnivores be better than challenging them? I felt unreasonably snubbed that my opinion had not been consulted.

And in the next instance, I chided myself. Let Chade and Dutiful and Elliania and Kettricken manage the dragons. Walk away, Fitz.

I lifted a tapestry and slipped away into the labyrinth of secret corridors that wormed its way behind the walls of Buckkeep Castle. Once I had known the spy-ways as well as I knew the path to the stables. Despite the passing years, the narrow corridor that crept through interior walls or snaked along the outer walls of the castle had not changed.