Полная версия:

Red Rose, White Rose

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Harper 2014

Copyright © Joanna Hickson 2014

Joanna Hickson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007447015

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007447022

Version: 2017-07-11

Dedication

For my intrepid and lovely sister Sue

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

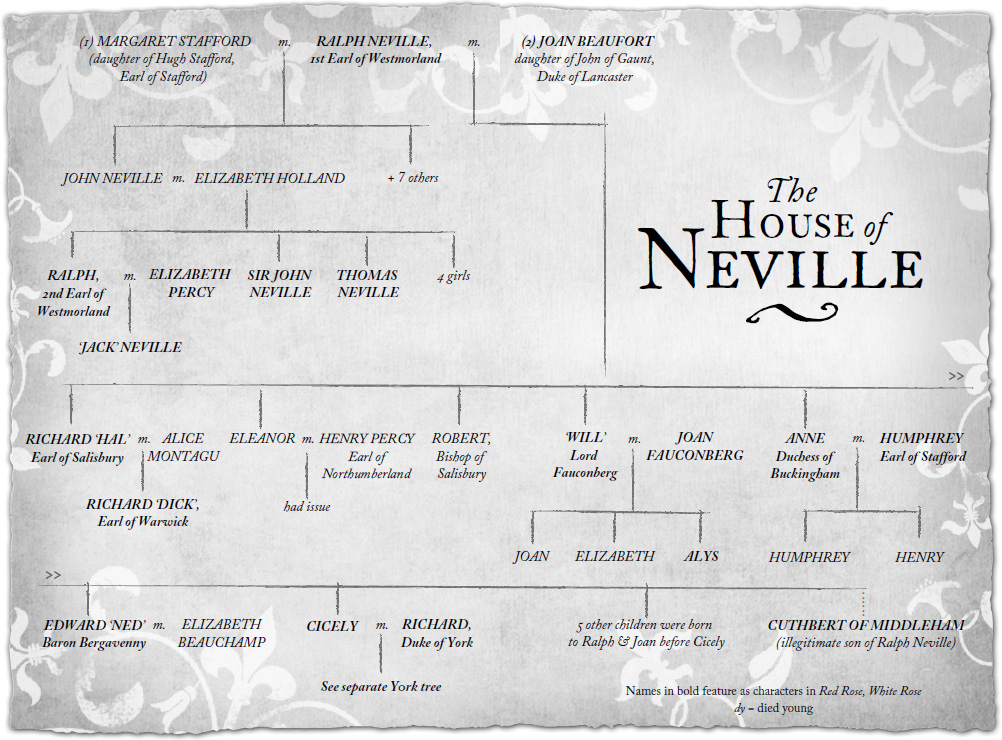

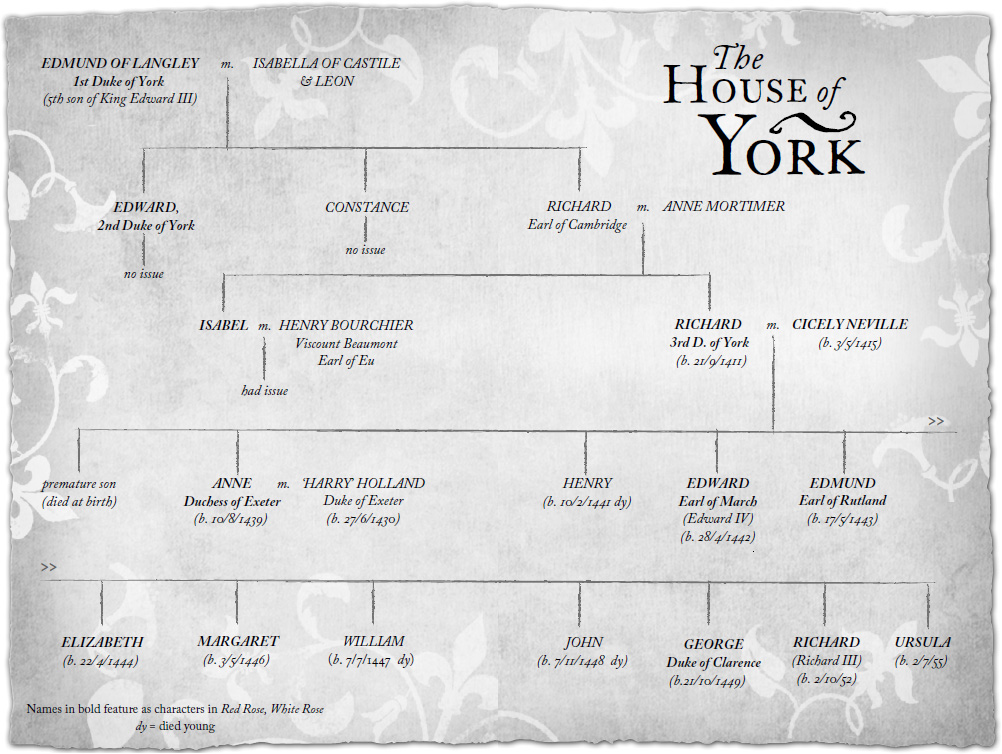

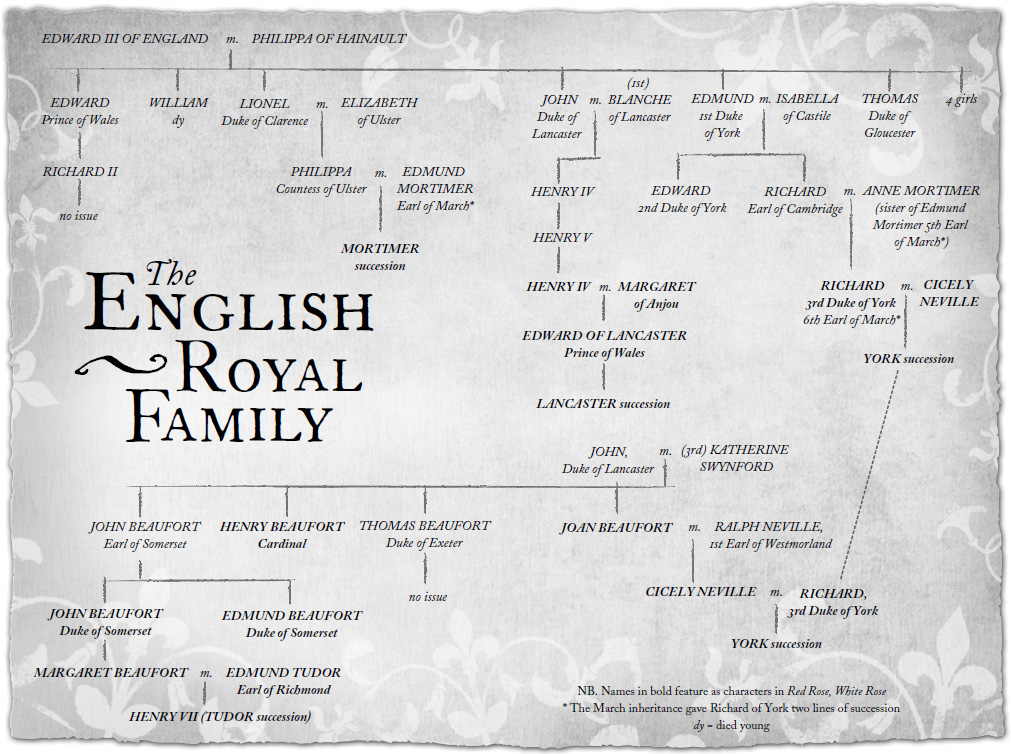

Family Trees

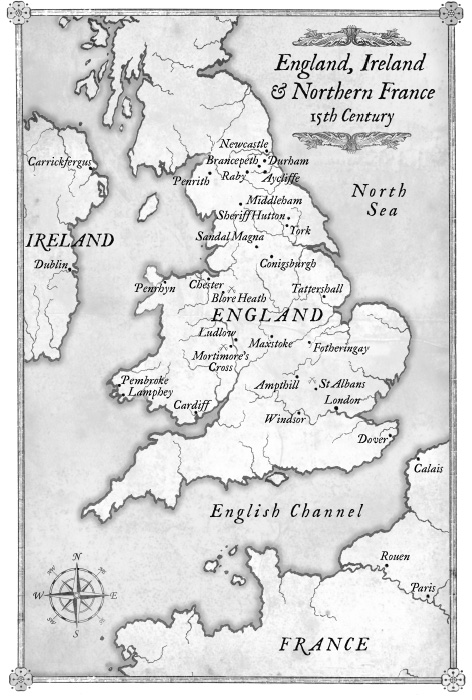

Map

Prologue

Part One: County Durham, England

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part Two: France

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Part Three: Fotheringhay Castle Northamptonshire, Coldharbour Inn & Westminster Palace, London

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part Four: Ireland & Northern England

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Part Five: Lincolnshire & Yorkshire

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Part Six: The Drums of War

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Keep Reading – THE AGINCOURT BRIDE

Keep Reading – THE TUDOR BRIDE

About the Author

By the same author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Provins, County of Champagne, France, 1275

At first there was only a subtle hint of fragrance borne on the breeze, an exquisite teasing of the senses. To the knight on his weary warhorse it was like the breath of God, lifting the hairs on the back of his neck and stirring the golden leopards on his banner.

‘It is the scent of roses!’ he cried to his companions. ‘In the Holy Land we called it God’s Incense.’

When the cavalcade breasted the hill ahead he reined in his horse with a gasp of wonder. All over the wide plain below stretched a carpet of red roses, covering the earth as far as the eye could see, as if a celestial gardener had scattered divine seed. The knight gazed in silent awe, struck by the power of the symbolism laid before him; that the single rose, an object of beauty and simplicity could, when massed with a myriad others, become a potent force, a source of mystery and strength. The words of a hymn sprang into his mind, which he had heard sung in the dust and heat of the Holy Land by choristers in his crusading army.

There is no rose of such vertue

As is the rose that bore Jesu,

For in this rose contained was

Heaven and earth in a little space.

‘If there is a heaven on earth,’ he declared, ‘it is surely here.’

The knight was Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, crusader brother to Edward I, King of England and known throughout Christendom as Edmund ‘Crouchback’ or ‘The Cross-Bearer’. Returning through France from his crusade, he was making a mercy mission to Provins where the Count of Champagne had recently died, leaving his young widow and their baby son vulnerable to abduction by neighbouring barons, eager to acquire access to the great wealth generated by the famous rose fields.

Grown from a single root brought back from Damascus by an earlier crusader, the precious roses were not just objects of beauty, they were an industry. Their dried petals became shards of perfumed sunshine to freshen the rushes on a rich man’s floor; their floral essence could be distilled into attar of roses to perfume a lady’s breast or diluted into rosewater for bathing and cooking; rose leaves were pounded into healing poultices and even the prunings, with their long, sharp thorns could be woven into fences for protecting flocks and crops.

But it was the rose of ‘vertue’ that Edmund held in his mind when he first encountered Blanche, the lady in distress. Wearing white robes of mourning, she held her baby in her arms and her face was sweet and troubled. ‘The Blessed Virgin has answered my prayers,’ she sighed as he kissed her hand. By the next rose harvest Edmund and Blanche were married and the red Damask rose became for him a talisman, a badge of honour which he bore on his shield and gave to his favoured followers; the Red Rose of Lancaster.

A hundred years later another Edmund, younger brother to the great John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was created Duke of York by their father, King Edward III. This Edmund aimed to better his brother in all things, including the heraldic symbol of his dukedom. He could not have the red rose so he chose the white, the lovely wild rose of England with its five creamy petals and fierce, hooked thorns. He declared the white rose superior to the red because it was native to the soil it grew in, spreading over the hills and valleys of England in great tangled brakes, delighting all with its airy fragrance and spangled masses of blooms but repelling any who tried to seize it. Edmund had his minstrels compose a song in praise of the white rose:

Of a rose, a lovely rose

Of a rose I sing a song.

Lyth and lysten, both old and younge

How the white rose becomen sprong,

A fairer rose to oure leking

Sprong there never in kynges lond.

During the next century, in the battle for supremacy between Lancaster and York, the red rose and the white were to scratch a bloody trail across the ‘kynges lond’, leaving England blighted and bleeding.

1

Langleydale, Co Durham

Cicely

I breathed deeply of the scented air that swept off the Teesdale fells. It carried the chill of snow-capped mountains and the smell of juniper. When I was a small child my father had perched me in front of him on his great warhorse and taken me out on the moors to teach me the names of the peaks and pikes that rolled towards the horizon to the north and west of our home. Now I identified them one after another all the way to Cross Fell, misty blue in the distance; Snowhope, Ireshope and Burnhope, Holwick, Mickle, Cronkley and Widdybank. Their names sang in my head like a psalm, accompanied by the moan of the wind over the rock-strewn slopes and the cries of the birds that haunted them.

When I turned my mare’s head to the east, her ears framed a view even more familiar. Each beck and stream from those high moors fed into the River Tees, which flowed through a valley ever-wider and greener as it meandered towards the coast. Dominating the upper reaches of this fertile basin was Raby Castle, the ancestral home of the Neville family – my family. Renowned as one of England’s great northern fortresses, Raby’s nine massive towers sprawled below me like the giants of legend; they loomed over the meagre mud-plastered cotts of the village beyond its moat. I had lived most of my seventeen years within those soaring walls. To my mother it was a palace, a great haven of security and splendour demonstrating infallibly the enormous wealth and power of the Nevilles, but to me it had become a prison. Often I had felt like a caged bird longing to fly. It was wonderful to be out, after a winter confined by its grey stones, up high above Langley Beck, relishing the wind in my face and the trembling anticipation of the hooded falcon on my fist.

‘Look lively, Cis! Stop admiring the view and start working that bird of yours.’

It was my brother who spoke. We Nevilles were a numerous family and I could count six brothers who still lived; some I liked better than others. Three of them were out hunting with me on that March morning, but this particular brother held a special place in my life. Dark and even of temper, Cuthbert was my personal champion, five years my senior and sworn to protect me for life by an oath made to our father before his death. He was an expert swordsman, had enormous skill with the lance and a physique unsurpassed among the knights of the Northern March. Nevertheless I did not let him order me about.

‘Selina will fly in good time, Cuddy, when the dogs put up some partridge. I do not fly her at inferior prey.’

His baptismal name was Cuthbert, after the great hermit-saint of the Holy Isle whose bones lay only five and twenty miles away in Durham Cathedral, but I used the nickname he had earned among his fellow henchmen at Raby for his close affinity with horses. Not only was Cuddy the local name for the saint, it was also one of the many northern words for a horse, particularly the small, strong, nimble pony which carried men and goods over the treacherous terrain of the border moors. Cuddy had the knack of getting a good performance out of even the most stubborn nag. It would not be boasting to say that I sat a horse as well as he did, since it was Cuddy who had taught me to ride, and I rode astride from the very first lesson, despite the disadvantage of wearing skirts.

His reaction to my protest was indignant. ‘Huh! It will be a miracle if your merlin brings down a partridge. They are twice her size.’

We were hunting game for the Easter feast that was just over a week away. The birds would hang until then to intensify their flavour, while we Christians completed our Lenten fast. Cuddy preferred chasing stag. On this hunt he was acting as my bodyguard and the captain of our armed escort. He carried no hawk and, in my opinion, knew little or nothing about them.

‘You may think that, big brother, but Selina can bring down snipe, which are the same size as partridge and fly a lot faster.’

I dropped my reins briefly to remove the crested hood from the little bird on my other fist and felt her claws clench expectantly over the thick leather gauntlet that protected my hand and wrist. Released from the imprisonment of the blindfold, the falcon blinked and her yellow eyes began to dart about, filled with anticipation at the sight of the moor and the busy spaniel quartering the heather ahead of us. My palfrey pranced excitedly as I gathered up the reins and I bent to murmur calming words in her ear.

In a loud explosion of noise a covey of partridge burst up from the ground. ‘Climb, Selina, climb,’ I yelled, releasing the merlin’s jesses and sending her off my fist as the game birds sped away from us, swerving and tumbling in panic.

For a few joyful seconds I watched the powerful beat of my falcon’s wings as she scaled the wind, gaining height for her stoop and then the spaniel let out a throaty growl of warning, which crescendoed into a volley of barks. Only twenty yards away half a dozen men wearing protective canvas jacks and wielding an assortment of rustic weapons rose as if from nowhere, like demons from the underworld, and ran snarling and yelling down the slope towards us, leaping over the straggling heather which had so successfully hidden their presence. They must have belly-crawled from the cover of the stunted trees that grew in a rocky cleft nearby, where the beck tumbled down a steep part of the fell-side.

Cuddy drew his sword. ‘Holy St Michael – reivers! They’re after the horses. Ride, Cis – ride for the castle! Stop for nothing. I’ll hold them off.’ He wheeled his horse to face the oncoming foe and charged at the front-runner, yelling the family call-to-arms. ‘À Neville! To me!’

From the corner of my eye I spied the first reiver fall as I set my horse’s head down the slope. There I saw my other two brothers, Will and Ned, throw off their hawks, draw their weapons and urge their horses into a gallop, hurtling past me to give Cuddy support and returning his warcry, their mouths wide, faces twisted into angry scowls. Pounding up the hill behind them, yelling defiance, came our escort of half a dozen armed horsemen.

Reivers were the universal enemy, even here on the southernmost edge of the Northern March. Within the miles of untamed territory between Scotland and England known as the Debatable Lands, title to land and property was hotly contested and the rule of law rarely successfully applied. Gangs of bandits operated freely and internecine feuds abounded but however much they fought amongst themselves, English landholders and their tenants were united in their hatred of the Scottish reiver clans – Armstrongs, Elliots, Maxwells and Johnsons, to name but a few. These rampaging villains swooped down from the hills without warning, sometimes in a large troop to raid a whole town or village, sometimes in a small posse to grab whatever plunder they could, robbing travellers at random, raiding a single farm or rustling a herd of cattle and driving the beasts to a secret muster deep in the mountains.

Cuddy had automatically assumed that these particular bandits were after our horses, a valuable commodity, especially when of good breeding and training as ours were. Since he and I had strayed a small distance from the rest of the hunting party perhaps they had not realized how many of us there were nor how well armed and skilled in combat. Considerably older than me, my brother William was not only a knight of some renown but held estates and a seat in parliament as Lord Fauconberg and had been accompanied to the hunt by a number of his young retainers, including the brother next to me in age, nineteen-year-old Edward, known as Ned. In this part of the world no knight or squire ever rode out in less than half-armour, belting on his sword and carrying a mace or battle-axe slung from his saddle-bow, so I was confident they would make short work of the attackers. The hunt servants, unarmed except for their hunting knives, obviously thought the same because they called in the dogs and retreated only a short distance before turning back to watch the skirmish. Despite Cuddy’s order to ride non-stop to Raby, I was tempted to follow suit, hoping to lure back my precious merlin Selina from wherever she had found a safe perch. However, even as the notion entered my head my own situation suddenly became perilous.

We had misjudged these reivers. They were not a small band of snatch-thieves willing to risk their lives in the hope of securing one or two valuable horses; they were a gang of bandits seeking an even richer reward. As I galloped past a grove of gnarled ash trees rooted in a sheltered hollow, six wild men mounted on ponies burst out from their cover to block my path. My speeding mare threw herself back on her haunches to avoid a collision and within seconds I found myself surrounded.

I wheeled the mare around, looking for help, but quickly realized that this ambush had been carefully planned. The smug grins on the faces of the surrounding horsemen confirmed this.

‘They will not see us, lady. We are hidden by the hill, so best to come quietly.’

The speaker’s face was disguised with dark, caked mud and he wore a dented metal sallet on his head, its visor pushed up. A camouflage spray of myrtle leaves tied over the helmet shadowed his eyes so that he resembled the evil green man depicted in church carvings. His cocky smile revealed rotting teeth. Despite my fear I felt a fierce surge of anger.

‘I do not know who you are, villain, but I am a Neville and Nevilles do not “come quietly”,’ I said, and throwing back my head, echoed the family warcry I had heard so recently on my brothers’ lips: ‘À Neville! Cuthbert, to me!’

The evil green man spoke sharply to his companions and a large, callused hand was clamped over my mouth from behind me. At the same time another man snatched the reins from my hands as yet another pulled my arms back and wound a cord around my wrists, tying them tightly together.

‘We ride!’ shouted the leader and all at once I found myself desperately struggling to remain in the saddle as, corralled in the midst of their horses, my mare was forced to bound clumsily up the steep side of the hollow. But once I had caught my breath and clamped my thighs to my horse’s sides, I realized that although my hands were tied my mouth was still free and I took advantage of the fact, renewing my screams for help, albeit in shrieks and jerks from my mare’s hunched leaps. A loud oath came from the leader and as soon as we reached flatter ground he held up his hand for a halt. I continued shouting while he kicked his horse up to mine, scrabbled in the front of his battered gambeson and finally pulled out a filthy kerchief.

‘For a well-born lady you screech like a fishwife but this should shut you up,’ he growled and retaliated by spitting into the kerchief before using it to gag my screams.

I twisted my head this way and that but without the use of my hands I was unable to prevent him pulling the damp, stinking cloth between my teeth and tying it at the back. My shouts were reduced to muffled moans and then silenced altogether as I retched at the foul taste on my tongue.

‘Calm down, my lady,’ the man sneered, ‘or I will have to throw you over my pommel and that will make a very painful ride.’

Forced to inhale through my nose, my eyes bulged as I fought to draw the air into my lungs. I knew I would have to stop struggling if I was to keep breathing and so although I glared daggers at him, I stopped grunting and wriggling.

His lip curled in contempt. ‘That is better. Right – onwards, comrades – to the forest!’

He set off again at a fast pace but as we began to climb more steadily on a drover’s track, I found it easier to stay in the saddle. And now I knew where we were headed – to Hamsterley Forest on the northern side of the dale. I also knew that if we got there the chances of my being rescued were minimal. It was ancient forest, deep and impenetrable. Even if a hue and cry were raised, it would be hours before the bloodhounds found my trail and beyond the forest the terrain was full of hidden ravines which I did not doubt that the reivers would know intimately. By using them as cover they could hustle me over the River Tyne and beyond Hadrian’s Wall before a search party got near. I tried to look back for any sign of help but very nearly fell off in the attempt and gave up in favour of staying on my horse.

‘Looking for a knight in shining armour, lady?’ lisped the reiver leading my mare. Under the brim of his ancient kettle helmet were bloodshot eyes, a wrinkled brown face, and a toothless grin. He looked about seventy, but with only rough sackcloth for a saddle he stuck to his steed like a limpet. ‘There’s none of their like around here,’ he went on. ‘But dinnae worry, all we want is a good price for your horse and a queen’s ransom for you. And mebbe you might dance for us a bit, eh? He-he!’ He found this notion so amusing that he made himself cough and splutter.

That use of the word ‘dance’ had a sinister ring to it and I wanted to smack the grin off his face, but all I could do was stick out my chin and fix my eyes on my mare’s forelock, willing her to avoid all hazards, since I could not steer her.

Another loud stream of oaths from the leader silenced the bearded man’s mirth but they were not aimed at him. On the crest of the hill, our path was crossed by a drove-road that ran from west to east, and that very knight-errant I had been mocked for seeking was approaching the junction, closely followed by a dozen men-at-arms. I could not believe my eyes. The chances of meeting a fully armoured knight and his retinue on a drover’s path in any season were almost nil, yet there he was. As soon as he sighted the reivers he drew his sword, obviously as surprised to see them as they were to see him.

The green man did not hesitate. He knew when the odds were stacked against him. ‘Run for it, lads,’ he yelled, clapping his heels to his pony’s sides. ‘Every man for himself. Dump the loot.’

In different circumstances I might have been offended by being described as ‘loot’ but at that moment there was pandemonium as my captors galloped away in all directions and my mare plunged off the path into the maze of rocks, lose scree and whin that formed the terrain of this high fell country. Horses are herd animals and naturally follow their leader but which other horse to follow my mare did not know and I could not help her, being gagged and tied, so she skidded and skittered and plunged and it was only a matter of time before she lost her footing and fell, tossing me off into the middle of a patch of gorse, which luckily broke my fall.

Having all the air knocked out of your lungs when wearing a gag creates a desperate situation. For several long minutes I wheezed and coughed and feared I might lose consciousness but eventually I managed to force enough air into my deflated lungs to pay attention to my plight. All around me I could hear the cursing of men and the clatter of stones as even the reivers’ agile dale-trotters tripped and slithered over the treacherous ground. My own mare lay a few yards off, hooves thrashing as she writhed and twisted, trying to get to her feet. When she finally managed it she stood on three legs, her sides heaving. There was no doubt she was lame; perhaps her leg was broken. Even if I could have caught her she was no longer rideable and, anyway, I doubted if I could mount without the use of my hands.