Полная версия:

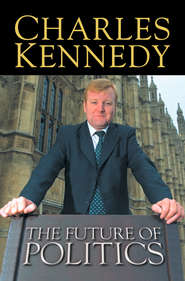

The Future of Politics

THE FUTURE OF

POLITICS

Charles Kennedy

DEDICATION

For my parents,

Ian and Mary Kennedy

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Introduction

WHY AREN’T THE VOTERS VOTING?

Chapter One

FREEDOM FROM POVERTY: THE FORGOTTEN NATION

Chapter Two FREEDOM TO BREATHE: THE GREEN FUTURE

Chapter Three FREEDOM FROM GOVERNMENT: PEOPLE AND THE STATE

Chapter Four FREEDOM TO INNOVATE: SCIENCE AND DEMOCRACY

Chapter Five FREEDOM TO GOVERN: THE GREAT DEVOLUTION DEBATE

Chapter Six FREEDOM WITHOUT BORDERS: BRITAIN, EUROPE AND THE CHALLENGE OF GLOBALIZATION

Conclusion A SENSE OF IDEALISM

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

This preface is being written at home in Scotland over the Christmas and New Year holiday period, 2000–2001. At the time of writing my thoughts and political preoccupations are very much focused upon what lies ahead during the next twelve months for British politics in general, and the Liberal Democrats in particular. By the time this paperback edition appears we will more than likely have been through a general election – or be in the middle of the campaign.

Politics and politicians have taken a further beating over the last year. In particular, as the hardback edition of this book went to press in the summer of 2000, something remarkable happened in British politics: direct action, in the form of the fuel blockades, came to the towns and villages of Britain. I refer, of course, to the fuel crisis.

It was remarkable for several reasons. First, such action, organized by individuals rather than trade unions, is rare in Britain. In some Western countries, particularly France, taking to the streets is a much-used part of the political process – and it has achieved its aims on many occasions. Indeed, only a fortnight earlier, the French authorities capitulated in the face of domestic protests over fuel – perhaps sending a message across the Channel. Usually, the British have done things more gradually, believing ultimately that all problems will, at least to some degree, be resolved by a general election.

The second remarkable feature of the fuel protests was the issue itself. There has been rumbling discontent over fuel prices for many years, but except in a small number of constituencies (my own included) it had never been a major election issue – and certainly was not one of the main reasons for the Conservatives’ electoral eclipse in 1997, despite all that they had done to increase fuel taxes.

However, surely by far the most notable feature of the fuel protest was what it said about the state of politics itself. From all the diverse voices of the fuel protestors, one message came through loud and clear: the public want honesty on tax, and they are not getting it. If fuel taxes are necessary to protect the environment, people want politicians to say so – they do not want to be told, as they were by a government insulting their intelligence by seeking to shift the goalposts, that fuel taxes have now become necessary to pay for public services. Shifting the goalposts was exactly what Labour did. All parties had supported the principle that fuel taxes had an environmental objective when Norman Lamont introduced the fuel duty escalator (an automatic annual increase in fuel duty above the rate of inflation) in 1993. Indeed, Gordon Brown’s 1998 Budget was big on the link between fuel duties and the environment. He said then that, ‘only with the use of an escalator can emission levels be reduced by 2010 towards our environmental commitments’. He also spoke of the government’s ‘duty to take a long-term and consistent view of the environmental impact of emissions’.1 But by September 2000, Gordon Brown was telling the nation that ‘the existing fuel revenues are not being wasted but are paying for what the public wants and needs – now paying for rising investment in hospitals and schools’.2 The subsequent opinion polls over that summer told their own story. The Conservatives’ standing increased at the expense of Labour, as the Opposition inevitably does when the government faces a crisis. But the Liberal Democrats did better in the polls too – and our message was not a knee-jerk pledge to cut taxes, but a simple, restated pledge to be transparent as to the specific purposes of tax revenues.

Following on from the fuel crisis, came the floods – the other side of the story where climate change is concerned. During the flooding it became rapidly apparent that politicians are not talking nearly enough about the big issues, such as climate change, and that these will make a massive difference to the way that we all live our lives in the decades to come. Unless they start to do so, politics will never reconnect with the people it is losing – and politics will have no future.

This book is about the future, but it is also about me and it is about us – the British. It is one person’s reflections on the United Kingdom, and that person’s reflections upon himself. What makes this Kennedy fellow tick? What makes him angry, what makes him sad? What fires his passion? By the way, does he possess passion? Why is he a Liberal Democrat, and who are these Liberal Democrats anyway?

The story begins in the West Highlands of Scotland in November 1959 and I cannot tell you where it might yet end. My first visit to London was not until the age of seventeen; my third visit was as a newly elected Member of Parliament in 1983. A friend put me up, in those first few crazy weeks, in his spare bedroom in Hammersmith. I didn’t know how you got to Hammersmith from Heathrow airport. I had no idea where Hammersmith stood geographically in relation to Westminster. It was a fast learning curve.

It was not until August 1999, when I was elected as Liberal Democrat leader by the party’s members, that I experieced again anything remotely comparable. The party leadership transforms your life almost out of all recognition, but for the better. You learn every day of the week, and you are never really off duty, but you experience a profound sense of duty in the process.

This book is part of that process. It is about attitudes and aspirations, hopes and fears. It is also about ambition. I am extremely ambitious for the Liberal Democrats, for two solid reasons. First, I believe that we are more correct in our diagnosis as to the nature of the problems of the body politic – and how they can be cured – than are the other parties; second, I am convinced that we will secure the opportunity to put these beliefs into governmental action.

Back to the West Highlands. If you had told me, when I was growing up, that one day not only would there be a Scottish parliament, but that it would involve the Liberal tradition at ministerial level, then I think I would have been ever so slightly sceptical. It has happened. My friend, Jim Wallace, now presides over the system of justice in Scotland.

Due to the initial illness and then tragic, premature demise of Donald Dewar, Jim has also exercised full First Ministerial authority on two separate occasions.3 Jim’s staple diet these days is red boxes, decision making, trying to get public policy more right than wrong. He is a Liberal Democrat making a serious difference to people’s lives; in December 2000 he became a Privy Councillor and was named ‘Scottish Politician of the Year’ by the Herald. In Opposition at Westminster you make sounds and faces; in the Scottish coalition, Liberal Democrats are taking decisions.

Leadership in contemporary politics has become too much about lecturing and not nearly enough about listening. Some politicians are prone to rant and rave, but Jim and myself have never been from that stable. We need more people of Jim’s sort in public positions. And we need much more liberal democracy in public life. I am determined to help secure such an outcome.

Mine has been a distinctly curious political lineage, all things considered. I joined the Labour Party, at home in Fort William, aged fifteen. As I describe later, that entanglement didn’t last very long. I soon found the dogmatic class war that many Labour activists were fighting thoroughly unpalatable. At the University of Glasgow I was sympathetic to the Liberals but joined the SDP, for which Roy Jenkins can be fairly and squarely blamed.

Out of the unhappy state of British politics in the late seventies, came Roy Jenkins’ famous 1979 Dimbleby Lecture, ‘Home Thoughts from Abroad’. Every so often in life, you hear someone articulate your own thoughts – and they do so with an elegance and eloquence which make you wish you had been able to say it yourself. Roy Jenkins’ Dimbleby lecture had that effect on me. He brought sharply into focus the unease that I, as an open-minded, pro-European, moderate-thinking Scot, felt about the choices that Labour and the Conservatives were offering the British people.

Roy offered a vision of the type of political party I wanted to join. He spoke of the need for a party of the radical centre to bring about constitutional and electoral reform at the heart of our political life, to end the failures of the two-party system. The new political system that resulted would allow parties to co-operate where they shared ideas. The new party that Jenkins saw leading these changes would also devolve power, while advancing new policy agendas for women, the third world and the environment. He spoke too of the need to establish ‘the innovating stimulus of the free market economy’ without the ‘brutality of its untrammelled distribution of rewards or its indifference to unemployment’.

The Dimbleby Lecture was a rallying cry for those who wished politics to move beyond the class war that it had become, and it struck many chords. It was a vision of a radical, decentralist and internationalist party, combining the best of the progressive Liberal and social democratic traditions. It was a vision of the party that the Liberal Democrats have become. From the first, I was clear that I wanted to be part of this new force in British politics. So when the SDP was launched in 1981, I was an early member. A blink or two later and I landed up as the youngest MP in the country, having defeated a Conservative minister in the process in Ross, Cromarty and Skye. There followed a lot of listening and, I hope, learning.

There is a popular, recurrent misunderstanding about the Liberal Democrat neck of the woods in politics. Many people – journalists and the wider public alike – seem to think that operating within the confines of the SDP, an SDP-Liberal Alliance, and the Liberal Democrats today, is somehow less demanding than being Labour or Conservative. Believe you me, it’s not. It is every bit as demanding and, to a certain extent, even more so.

You have to fight for every column inch. You get two questions on a Wednesday afternoon at Prime Minister’s Question Time – when the leader of the Opposition can rely on six. Contrary to popular opinion, the job of leader does not carry a salary. No complaint there. You occupy a certain space in the unwritten constitution of the land – from State occasions to the Privy Council – but somehow you are not quite part of the in-crowd. It is all very curious.

Since 1983 my world of politics has changed out of all recognition, and not just due to the party’s achievement and progress over nearly two decades – the landscape of politics itself has altered. The key issues that set the tone for much of the twentieth century – socialism v. capitalism, public v. private ownership – are now no longer debated. Today the issues are quite different – professionalism v. the market, interdependence v. nationalism, community responsibility v. self-interest.

There is also the issue of women’s rights and role in society, which is rightly coming far more to the fore of the political agenda. It should be a core issue for all in politics Despite the advances that women have made since receiving the vote, many still do not have equal life chances to men. A disproportionate number of women still suffers conditions of poverty in the UK. For women in work, the problems of part-time employment make a particular impact; and although women comprise 44 per cent of the workforce, the proportion of women in managerial and administrative roles is still only 32 per cent. Politicians are gradually recognizing these inequalities and deliverying policies which meet women’s needs and support their aspirations.

We are also all coming to terms with post-devolution party politics. As a Scot I am acutely conscious of that fact; so is Prime Minister Blair, who has admitted his mistake in interfering in the politics of the Welsh Labour Party over the election between Rhodri Morgan and Alun Michael.4 We even have the irony of the Conservative and Unionist Party leader seeming to welcome the fact that a combination of devolution and a degree of proportional representation has brought life back to the political corpse which his party had become in Scotland and Wales. Altered images indeed.

On the key issues of today, Liberal Democrats are in a better position than the other parties to set the agenda. We start off by trusting people. In 1865, Gladstone defined Liberalism as ‘a principle of trust in the people only qualified by prudence’, contrasting it with the Conservatives’ ‘mistrust of the people, only qualified by fear’. And I am always struck by Vernon Bogdanor’s characterization of the nineteenth-century Conservative Party as pessimistic, fearful of democratic change, and inclined to rely on central rather than local government for political solutions. Little has changed in the modern Conservative Party. We are also different because we are strong defenders of the spirit of public service: we value the expertise of professionals, and want to fund them so that they can do their jobs effectively, particularly in health and education. We want to promote social justice through health and education. We alone, apart from the Green Party, stress the environment as a fundamental part of politics. We are an internationalist party, comfortable with playing a constructive role in Europe, but ready to reform it, and look beyond European frontiers. We recognize that women and ethnic minorities still face enormous barriers to involvement in public life. We are willing to champion the needs of sometimes unpopular minorities – essential at a time when the Conservative Party is willing to exploit the debate on asylum seekers for party ends. And above all, we tie these concerns together with a commitment to the liberty of the individual, a cause that the other parties cannot lead – Labour has a strong authoritarian streak, while the Conservatives tend to equate liberty with rampant market forces.

This is the territory upon which the Liberal Democrats now operate. Society seems to be defined by near-instantaneous flitting images; as a consequence we have to be fleet of foot politically. Our past weakness, support too evenly spread in every conceivable sense, is today a source of potential strength. We must be sharp, but, emphatically, we must not be concentrated only in some parts of the country.

Now exactly what, I hear you say, does he mean by that? Allow me to explain. There is no point in this or any other political party existing or campaigning without a common purpose and a collective attitude. The Liberal Democrats have that – and it is frequently infuriating. It questions, it ridicules, it gives the awkward squad an honorary degree for their troubles. The party dislikes top-down policies. And it puts people like me in their place. Frequently.

However, it is part of the spirit of the age. People do not trust their politicians much; there is a collective dubiousness out there which is a legitimate cause for concern. Certainty has given way to uncertainty, the council estate – where the residents tended to vote en bloc one way because they all worked at the same local factory – has changed out of recognition. That local factory, or coalmine, or steelworks, or shipyard, probably no longer exists. And the council estate these days is full of families who have bought their own homes and whose children send mail down the phone line.

But has the political establishment changed accordingly? Not really. We carry on, pretty much upon the same tram-lines, affecting modernization yet not, somehow, giving real vent to it. The nineteenth-century building that houses parliament all too often contains the remnants of nineteenth-century habits. We are failing citizens as much as we are failing ourselves. And yet, away from Westminster, 2000 showed that all is not lost.

Things have got better since May 1997. In particular, the government has spread more power throughout Britain through devolution than any Conservative government would have ever contemplated. And in that time we have had clear signs of how disastrous a William Hague-led Conservative government would be: slashing taxes for the sake of it, retreating from Europe, and still pretending that there can be improvements in health and education without paying for them.

The result of the Romsey by-election on 4 May 2000, coupled to our exceptional 28 per cent share of the vote at that day’s local elections, demonstrates that the British people realize what is involved. In particular, it is clear that people are not taken in by Mr Hague’s populist, saloon-bar rhetoric on asylum seekers. After the last election, people said the Conservative Party could sink no lower. But William Hague’s behaviour did sink lower, and he got his just deserts from the people of Hampshire.

Nobody should underestimate the significance of that result. The Conservatives, while in opposition, have only twice before in the last hundred years lost an incumbent seat to the Liberal tradition at a parliamentary by-election. The first was in Londonderry in 1913, remarkably, given that the Liberals were in government. The second was the 1965 triumph in the Scottish Borders of a young man called David Steel.

There are, surely, two big implications which flow from the upheaval in Hampshire. First, there is no genuine, far less gut, enthusiasm out there for the William Hague Conservative Party. His narrow, jingoistic approach has next to no broad, public appeal. The Romsey result cannot be dismissed as the usual ‘mid-term protest against a Conservative government’. There is no Tory government to protest against. On the evidence of Romsey, the Conservative Party is less popular than it was when it met its nemesis on 1 May 1997, and after the next general election there will still be no Conservative government to protest against. Since Romsey, moderate support for the Conservative Party has continued to fall away, and I was delighted to welcome Bill Newton-Dunn, the Conservative MEP, into the Liberal Democrat fold in November 2000.

Second, people have clearly learnt one of the major lessons of the 1997 general election: that it is vital to look at the local situation when casting your vote. People are no longer being guided simply by national trends or old loyalties when voting. They are looking at how they can best deploy their ballot with the maximum effect. In Romsey that meant that Labour voters made their vote really count – some for reasons of disillusion, others because they see an alternative Liberal Democrat opposition which they find more attractive to the administration of the day. It is now clear that the 1997 experience is being repeated, and voters are regularly prepared to use their votes with lethal intent where it can matter. I have this year chastised the BBC, for example, over their tendency to speak in terms of ‘the two main political parties’. Apart from ignoring the disparate and distinct political systems at work within Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, it also overlooks electoral reality where the Liberal Democrats are concerned. In truth, as in Romsey, across large swathes of the country, we now have varied patterns of two-party contests – involving all three UK political parties.

I want things to get still better, and they can. In his Dimbleby Lecture, Roy Jenkins mapped out an approach to our political process which has been more than vindicated by events. Quite simply, he was correct. If, as a country, we had listened to and acted upon his prognosis, then a lot of subsequent history would have been different.

Which brings me to today. I believe that the individual is now king, the consumer is in charge. It is right to opt for interests of the individual and the community rather than those of the state. Ask Tony Benn or Tony Blair what they think instinctively about the structure of society, and their answers will tend to centre on the jobs people do and how much they earn. Ask most Conservative politicians and you will find that the Thatcherite mantra of ‘no such thing as society’ still dominates William Hague’s party. Ask a Liberal Democrat and they will respond in terms that stress the relation of individuals to their communities.

It is an altogether different approach to life which needs to be understood clearly. We are in politics to promote the liberty of the individual – the best life chances for all, whoever or wherever they are. That is the core value at the heart of this book, at the heart of my politics and at the heart of the party I lead.

INTRODUCTION: WHY AREN’T THE VOTERS VOTING?

‘I’m not political’ is a phrase I used to hear a great deal. Even in the ferment of Glasgow University in the seventies I was occasionally pulled up sharp when fellow students told me that their interests didn’t extend to what I saw as the ‘big issues’ of the day: nationalization, inflation, trade union power, unemployment and Scottish devolution.

Of course, now that I am an MP, dwelling for the large part in a world populated by fellow Members, journalists, party stalwarts and others intimately involved with the theory and practice of politics, I don’t hear it so often, but I’m fully aware that ‘out there’ in the real world, being ‘political’ does not always mean caring about how the country is run and trying to do something about it. It means something quite different, for instance, rigidly holding a set of outdated principles, having faith in and being involved in a process that for many people has no currency, and it means sleaze. To be ‘political’ is akin to admitting that you are a trainspotter or a collector of antique beermats – a crank, and not always a harmless one.

It’s not just ‘political people’ who suffer as a result of this perception. For a large percentage of British people, the whole political process is deeply boring. It’s obscure, it’s impenetrable and, most importantly, it doesn’t matter if you understand it or not, because – so the logic goes – it doesn’t make any difference. Twenty years ago, it was still possible to find pubs where signs above the bar said ‘No politics or religion’, presumably because they were the two subjects most likely to cause a fight. Nowadays, you never see it, because either people don’t discuss politics at all, or, if they do, it’s conducted with such apathy that the chief danger is that the participants will fall asleep.

I was chatting with an acquaintance recently. I asked him if he’d seen the satirist and impersonator Rory Bremner on TV last night. He shook his head. ‘He does too many politicians,’ he complained, ‘so I ended up watching the snooker.’ I am not, I hope, out of touch. But it had never occurred to me that some people might find his show uninteresting precisely because a large part of its content is political satire. In essence my acquaintance was saying that politics is a turn-off, something that makes you want to change channels.