скачать книгу бесплатно

I think of the interview I did a few months ago. Mum and Dad and I had always refused until then. But this was for a local newspaper, to publicise the charity. It seemed important to us, as the ten-year anniversary of your disappearance drew near. I talked about everything I do. The personal safety classes, the support group for family members of victims, the home safety visits, the risk assessment clinics.

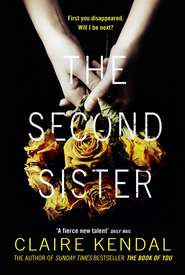

There was no mention of you, but Mum and Dad were still worried by the caption that appeared beneath the photograph they snapped of me. Ella Brooke – Making a Real Difference for Victims. My arms are crossed and there is no smile on my face. My head is tilted to the side but my eyes are boring straight into the man behind the camera. I look like you, except for the severe ponytail and ready-for-action black T-shirt and leggings.

Could that photograph have set something off? Set someone off? Perhaps I hoped it would, and that was why I agreed to let them take it.

I catch Luke’s hand and pull him back to me. ‘Probably a rambler. It’s morning. It’s broad daylight. We are perfectly safe.’

‘So you don’t think it’s an axe murderer.’ He says this with relish, ever-hopeful.

‘Not today, I’m afraid.’

‘Well if it is, you’d kick their ass.’

‘Don’t let Granny hear you talk like that.’ The sun stabs me in the head – warmth and pain together – and I squeeze my eyes shut on it for a few seconds, trying at the same time to squeeze out the worry that somebody is watching us. I am also trying – and failing yet again – to lock out the images of what you would have suffered if Thorne really did take you.

‘Do you have a headache, Auntie Ella?’

Luke doesn’t know he pronounces it ‘head egg’. I find this charming, but I worry that he may be teased.

Should I correct him? I didn’t imagine I’d be buying up parenting books when I was only twenty, and that they would become my bedtime reading for the next decade. They don’t usually have the answers I need, but I know that you would.

‘No headache. Thank you for asking.’ I smile to show Luke that I mean it.

‘I think Mummy would like me to live with you.’

I love how he calls you Mummy. That’s how Mum and Dad and I speak of you to him. I wonder if we got stuck on Mummy because you never had time to outgrow it. Mummy is the name that people tend to use during the baby stage. You were never allowed to become Mum. Or mother, perhaps, though that always sounds slightly angry and over-formal.

‘If I live with you part of the time, can we get more of her things in my room?’

‘What things do you have in mind?’

‘Granny put her doll’s house up in the attic.’

‘It’s my doll’s house too.’ As soon as the words are out of my mouth, I realise that I sound like a little girl, fighting with you over a toy.

Luke smiles when he mimics our father’s reasoned tone. ‘Don’t you share it?’

‘Yes.’ I lift an eyebrow. ‘So you’d like a doll’s house?’

‘No. Of course not. I’m a boy. I don’t like doll’s houses.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with a boy liking doll’s houses.’

‘Well I don’t. But why would Granny put it out of the way like that?’

‘It hurt her to see it, Luke.’

He scowls. ‘It shouldn’t be hidden away in the attic. Get it back from her.’ He sounds like you, issuing a command that must be obeyed.

Three crows lift from a tree, squawking. Luke and I snap our heads to watch them fly off, so glossy and black they appear to have brushed their feathers with oil.

‘Do you think something startled them?’ He takes a fire leaf from his pocket.

‘Probably an animal.’

He is studying the leaf, tracing a finger over its veins. He doesn’t look at me when he says, super casually, ‘Can you make Granny give you that new box of Mummy’s things?’

There’s a funny little clutch in my stomach. I am not sure I heard him right. ‘What things?’

‘Don’t know. Stuff the police returned to Granny a couple weeks ago.’

‘Granny didn’t tell me that. How do you know?’

‘I’m a good spy. Like you. I heard her talking about them with Grandpa.’

‘Did Granny open it? Did she look in it?’

‘Not that she mentioned when I was listening.’

‘Did she say anything about why the police finally returned Mummy’s things?’

‘Nope. Get the box too. Make Granny give it to you.’

Getting that box is exactly what I want to do. Very, very much. ‘Okay,’ I say, though I mumble secretly to myself about the challenge of making our mother do anything. Our mother gives orders. She does not take them.

‘Auntie Ella?’

‘Yes.’

‘She would have come back for me if she could have, wouldn’t she?’

I think of one of the headlines that appeared soon after you vanished, claiming you’d run away. I put my arms around him tightly. We have always tried to protect him from such stories. Since last week’s spate of new headlines about Thorne, we have been monitoring Luke’s Internet use even more carefully. But we can’t know what he might have stumbled on, and I am nervous that a school friend has said something.

I kiss the top of his head and inhale. We have only been out for forty minutes but already he smells like a puppy who has run all the way back from a damp walk. ‘She would have come back for you.’ It is not raining but my cheeks are wet.

Luke wriggles out of my arms. He wipes at his cheeks too. ‘Are you sure?’

‘One hundred per cent. Nothing would have kept her from you if she had a choice.’

He bites his lower lip and looks down, scrunching his fists over his eyes.

Was I right to tell him these two true things, one beautiful and one too terrible to bear? That you were driven by your love for him, and that something unimaginably horrible happened to you?

Another thought creeps in, a guilty one. Is it easier for me to imagine you suffering a terrible death than to contemplate the possibility that you made a new life for yourself somewhere, as the police have sometimes suggested? I think of Thorne and shudder, absolutely clear that the answer is no.

‘She wanted you so much.’ It is extremely difficult to get these words out, but somehow I do, in a kind of croak.

‘It’s okay, Auntie Ella.’ He has so much courage, this boy, as he takes his fists from his eyes and comforts me when I should be comforting him. He waits for me to catch my breath. ‘I found a picture of her holding me,’ he says. ‘It’s one I hadn’t seen before. At first I thought it was you. You look like her.’

‘I think maybe that’s more true now than it used to be.’

‘Because you’re thirty now.’

‘Thanks for reminding me.’

‘I know. It’s really old.’

I stifle a mock-sob.

‘Sorry,’ he says.

‘You look stricken with remorse.’

‘I’m just saying it because now you’re her age. That’s why you’re looking so much more like her. You can see it in that newspaper picture of you too.’ He clears his throat. ‘Did you really try everything you could to find her?’

Did I? At first we barely functioned. Mum didn’t leave her bed. Dad stumbled around trying to make sure we had what we needed, cooking and cleaning and shopping, trying to get Mum to eat. I lurched through the house, trying to care for a two-and-a-half-month-old baby. Mostly we were reactive, answering the police questions, giving them access to your things. But we got in touch with everyone we could think of, did the appeals.

I stuck pictures of your face to lampposts, between the posters of missing cats and dogs. One of them stayed up for a year, fading as rain and wind and snow hit it, flapping at a bottom corner where the tape came off, dissolving at the edges but miraculously holding on.

I tell Luke as much of this as I can, as gently as I can, but he shakes his head.

‘I need you to try again,’ he says. ‘I need you to. I need to know. Even if it’s the worst thing, I need to.’ His voice rises with each sentence.

I grab a bottle of water from my jacket pocket and pass it to him. He gulps down half.

‘Is this why you want me to get her things from Granny?’

‘Yes.’ He wipes his mouth with the back of his hand. ‘You have to. Tell me you will. You have to look at everything.’

‘The police already did.’

‘No they didn’t. I hear much more than you think after I’ve gone to bed. I’ve heard all of you say how useless they are. Except Ted.’

I inhale slowly, then blow out air. ‘Okay.’

‘You’ll do it?’

I nod. ‘I will.’ My stomach drops as if I am running and an abyss has suddenly opened in front of me. Because there is something I can do that we haven’t tried before. I can request a visit with Jason Thorne. I reach for Luke’s hand. ‘But only on one condition.’

‘What?’

‘You will have to trust my judgement about what I can share with you.’

‘If you mean you might have to wait a little while, yeah. Like, until I’m a bit older. But you can’t not ever tell me.’

Thinking about Jason Thorne makes it hard to breathe. The possibility of Luke knowing about him makes it even harder. But I manage to keep the pictures out of my head.

‘I need to do what I think is best for you, Luke. It’s going to depend on what I find out. And you need to be prepared for the possibility that this might be nothing at all – that’s what’s most likely.’

‘I guess that’s the best agreement I can get.’

‘You guess right.’

His forehead creases. ‘There’s something else that bothers me,’ he says.

I am beginning to think I may actually be sick. ‘Tell me.’ I realise I’m holding my breath.

‘Granny says you didn’t do well enough on your exams because you didn’t go back to University afterwards.’

Afterwards. He never says ‘after Mummy disappeared’ or ‘after Mummy vanished’. There is before. There is after. The thing in between is too big for him to name.

But at least he isn’t worrying about Jason Thorne. This is easy, compared to that. ‘I did go back,’ I say. ‘But they made special arrangements for me to do it from a distance so I could help Granny and Grandpa take care of you.’

‘But Granny says you should have done better. She says you wanted to be a scientist, but I heard her telling Grandpa that Ted was distracting you even before you moved back home. It’s not really Ted’s fault, is it?’

‘It’s nobody’s fault, and I wanted to be a biology teacher, not a scientist. But I don’t any more. The charity work is important – it means so much to me.’ I smooth his hair again, silky like yours, silky like mine. This time, I am not ambushed by an image of Thorne grabbing you by it.

‘It was my fault,’ Luke says. ‘You wouldn’t have messed up your degree if it weren’t for me.’

‘Luke,’ I say. ‘Look at me.’ I tip up his face. ‘Being your aunt is the best thing that has ever happened to me. That is definitely your fault.’

‘And Mummy’s,’ he says.

‘Yes. And Mummy’s. I miss her so much and you are the only thing that makes it hurt less. Looking after you taught me more than those lecturers ever could. I wouldn’t have wanted to do anything else. It’s what I chose.’

His head whips round. ‘There’s that coughing noise again.’ We both listen. ‘And that’s a different sound. Like somebody tripped in the leaves.’

‘Probably someone on their morning walk. Someone clumsy with a cold.’

‘Should we look?’

‘They’ll be gone before we get there.’ I take his hand. ‘If it’s really a spy, he’s not very good, is he?’

‘Not as good as me. Plus he won’t know what he’s up against with you.’

‘Let’s go in. Granny promised to make pancakes for breakfast.’

‘I’d better tell Granny and Grandpa about what we heard.’

‘We can tell them together. And you know that if anybody comes near the house, one of the cameras will pick him up. I’ll check the footage before I leave. You don’t have to worry.’

He nods sagely. ‘Can you stay for the afternoon and take me to my karate lesson?’

‘I’d love to. I’ll have to rush off as soon as you finish though. I promised Sadie I’d go to her party.’

‘Is it her birthday?’

‘It’s to celebrate moving in with her new boyfriend.’