Полная версия:

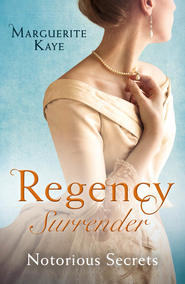

Regency Surrender: Notorious Secrets: The Soldier's Dark Secret / The Soldier's Rebel Lover

Born and educated in Scotland, MARGUERITE KAYE originally qualified as a lawyer but chose not to practise. Instead, she carved out a career in IT and studied history part-time, gaining first-class honours and a master’s degree. A few decades after winning a children’s national poetry competition she decided to pursue her lifelong ambition to write, and submitted her first historical romance to Mills & Boon. They accepted it, and she’s been writing ever since. You can contact Marguerite through her website at: www.margueritekaye.com

Regency Surrender: Notorious Secrets

The Soldier’s Dark Secret

The Soldier’s Rebel Lover

Marguerite Kaye

www.millsandboon.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-474-08543-4

REGENCY SURRENDER: NOTORIOUS SECRETS

The Soldier’s Dark Secret © 2015 Marguerite Kaye The Soldier’s Rebel Lover © 2015 Marguerite Kaye

Published in Great Britain 2018

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Table of Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

The Soldier’s Dark Secret

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Epilogue

Historical Note

The Soldier’s Rebel Lover

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Epilogue

Historical Note

About the Publisher

The Soldier’s Dark Secret

Marguerite Kaye

Chapter One

England—August 1815

The small huddle of women and the bedraggled children who clung to their skirts stared at him as one, wide-eyed and unblinking, struck dumb and motionless with fear. Only the compulsive clutching of their mother’s protective fingers around the children’s shoulders betrayed the full extent of their terror. He was accustomed to death in combat, but this was a village, not a battlefield. He was accustomed to seeing enemy causalities, but these were civilians, women and young children...

Jack Trestain’s breathing became rapid and shallow as he tossed and turned in the throes of his recurring nightmare. He thrashed around on the sweat-soaked sheets. He knew he was dreaming, but he couldn’t wake from it. He knew what was coming next, but he couldn’t prevent it unfolding in all its horror.

His boots crunched on the rough sun-dried track as he walked, stunned, around the small village, his brain numb, unable to make sense of what his eyes were telling him. The sun burned the back of his neck. He had lost his hat. A scrawny chicken squawked loudly, running across his path, making him stumble. How had the mission turned into such a debacle? How could his information, his precious, carefully gathered knowledge of the enemy’s movements, have been so wrong?

It was not possible. Not possible. Not possible. The words rang in his head over and over. He was aware of his comrades’ voices, of orders being barked, but he felt utterly alone.

The cooking fires were still burning. From a large smoke-blackened cauldron the appetising aroma of a herb-filled stew rose in the still, unnaturally silent air. He had not eaten since yesterday. He was suddenly ravenous.

As his stomach growled, he became aware of another, all-pervading smell. Ferrous. The unmistakable odour of dried blood. And another. The sickly-sweet stench of charred flesh.

As the noxious combination seared the back of his throat, Jack retched violently, spilling his guts like a raw recruit in a nearby ditch. Spasm after spasm shook him, until he had to clutch at the scorched trunk of a splintered tree to support himself. Shivering, shaking, he had no idea how long the girl had been looming over him...

It was the fall that woke him. He was on the floor of his bedchamber, clutching a pillow. He had banged his head on the nightstand. The ewer had toppled over and smashed. The chambermaid would think him one of the clumsiest guests she’d ever encountered. His nightshirt was drenched, the contents of the jug adding to his fevered sweat. His head was thumping, his jaw aching, and his wrists too, from clenching his fists. Wearily, Jack dragged himself to his feet and, opening the curtains, checking the hour on his pocket watch. It was just after five. He’d managed to sleep for a total of two hours.

Outside, morning mist wreathed the formal lawns which bordered the carriageway. Opening the casement wide, he leaned out, taking ragged breaths of fresh air. Damp, sweetly herbaceous air, not the dusty dry air of far-off lands, that caught in your lungs and the back of your throat, that was so still all smells lingered, and you carried them with you on your clothes for days afterwards.

Jack swallowed hard, squeezing his eyes tight shut in his effort to block out the unwelcome memory. Slow breaths. One. Two. Three. Four. Open your eyes. Moist air smelling of nothing but dew. More breaths. And more.

Dammit! It had been two years. He should be over it by now. Or if not over it, he should have it under control. He’d been coping perfectly well in the army—more or less. He’d been dealing with it—mostly. Functioning—on the whole. He hadn’t fallen apart. He’d been able to control his temper. He’d even been able to sleep, albeit mainly as a result of exhaustion brought on by a punishing schedule of duties. Only now, when he was free of that life, the very life that was responsible for creating his coruscating guilt, it was haunting his every waking and sleeping moment.

Dear God, he must not fall apart now, when it was finally all behind him. He had to get out of the house. He had to get that smell out of his head. Exercise, that’s what he needed. It had worked before. It would work again. He would make it work again.

His forearm had finally been released just yesterday after weeks in a cumbersome splint. Jack flexed his fingers, relishing the pain which resulted, his toes curling on the rug. He deserved the pain. A damned stupid thing to do, to fall from his horse, even if his shoulder had just been torn open by a French musket. Quite literally adding insult to injury.

Take it easy, the quack had advised yesterday, reminding him that he might never recover his full strength. As if he needed reminding. As if it mattered now. ‘As if anything matters,’ Jack muttered to himself, pulling off his nightshirt and throwing on a bare minimum of clothes before padding silently out of the house.

The sun was beginning to burn the mist away, drying the dew into a fine sheen as he set off at a fast march through the formal gardens of his older brother’s estate. Jack had been on active service in Egypt when their father died, and Charlie inherited. In the intervening years, nearly all of which Jack had spent abroad on one military campaign or another, Charlie had added two wings to their childhood home, and his wife, Eleanor, had redecorated almost every single room. The grounds, though, had been left untouched until now. In a few weeks, the extensive new landscaping programme would begin, and the estate would be transformed. The lake, towards which he now made his way, through the overgrown and soon-to-be-uprooted Topiary Garden, would be drained, dredged, deepened and reshaped into something that would apparently look more natural.

He stood on the reedy bank, inhaling the odours so resonant of childhood: the fresh smell of grass, the cloying scent of honeysuckle and the sweetness of rotting vegetation laced with mud coming from the lake bed. There was never anyone around at this time of day. It was just Jack, and the ducks and whatever fish survived in the brackish water of the lake.

Divesting himself quickly of his few garments, he stretched his arms high above his head, took a deep breath, and plunged head first into the water. Though it was relatively warm on the surface, it was cold enough underneath to make him gasp. Opening his eyes, he could see little, only floating reeds and twigs, the mixture of dead leaves and sludge churned up by his splashy entry. He broke the surface, panting hard, then struck out towards the centre, his weakened right arm making his progress lopsided, forcing his left arm to compensate as he listed to one side like a sloop holed below the waterline by a cannon.

Ignoring the stabbing pain in his newly healed fracture and the familiar throbbing ache in his wounded shoulder, Jack gritted his teeth and began to count the lengths. He would stop when he was too exhausted to continue, and not before.

* * *

Celeste Marmion had also been unable to sleep. Attracted by the soft light of the English morning, so very different from the bright blaze of the Côte d’Azur where she had been raised, she had dressed quickly and, grabbing her notebook and charcoals, decided to reconnoitre the grounds of Trestain Manor before facing her hosts at breakfast. Arriving late last night, the brief impression she had had of her new patrons, Sir Charles and Lady Eleanor Trestain, was pretty much as she had expected. He was the perfect gentleman, rather bluff, rather handsome, his smile kind, though his manner veered towards the pompous. His wife, a slender and very tall woman with a long nose and intelligent eyes, reminded Celeste of a highly-strung greyhound. Lady Eleanor was a good deal less welcoming than her husband, giving Celeste the distinct impression that she was placing her hostess in a social quandary, for although Sir Charles had welcomed his landscape painter as a valued guest, Lady Eleanor seemed more inclined to treat her as a tradesperson.

‘Which is perfectly fine by me. I am here for my own reasons, not to play the serf in order to placate a social snob. Lady Eleanor is really quite irrelevant in the grand scheme of things,’ Celeste muttered to herself as she made her way through a magnificent but dreadfully neglected Topiary Garden.

She could hardly believe that she had finally made it to England. It had been her goal ever since January, when she had received that fateful letter. It had been a terrible shock, despite the fact that they had been estranged for years, to learn that she would never see her mother again. She had thought herself completely inured to Maman’s coldness, but for a few days after learning of her death, Celeste had been left reeling, assailed by a maelstrom of emotions which struck her with a force that was almost physical.

She had, however, quickly regained her equilibrium. After all, her mother had been more of an absence than a presence in her life for as long as she could remember, even before Celeste had been callously packed off to boarding school at the age of ten. It should make no difference to Celeste that the house in Cassis was closed up, for she never visited. It should make no difference that there was now no possibility of any reconciliation. She had never understood her mother’s attitude towards her, the cause of their gradual and now final estrangement, but she had long decided not to let it be a cause of hurt to her. Until she had received that blasted letter which hinted at reasons, mysterious reasons, for her mother’s heartless indifference.

Celeste had tried very hard in the weeks after that letter to carry on with her perfectly happy, perfectly calm and perfectly ordered and increasingly successful life, but the questions her mother had raised demanded to be answered. Until she knew the whole story, until she knew the truth behind those hints and revelations, Maman’s life was an unfinished book. Celeste had to discover the ending, and then she could close the cover for ever. It was an image she found satisfying, for it explained away quite nicely that churning feeling which kept her awake at nights when she thought of her mother. Guilt? Hardly. Her whole life she had been the innocent victim of a loveless upbringing. And of a certainty it was not grief either. In order to grieve, one had to care. And she did not care. Or, more accurately, she had taught herself not to care. She did feel anger sometimes, though why should she be angry? She did not know, but it did not sit well with the self-contained and independent person she had worked so hard to become. And so she had come to England to find some answers and close an unhappy chapter in her life.

Napoleon’s escape from Elba in March earlier in the year had put paid to Celeste’s original plans for her trip here. As France and Great Britain resumed hostilities, she waited restlessly for the inevitable denouement on the battlefield, guiltily aware that her impatience was both unpatriotic and more importantly incredibly selfish. She knew nothing of war save that she wished it would not happen. She cared not who won, provided that peace was made. Until Waterloo, like almost every other person of her acquaintance, she managed to close her eyes to the reality of battle. After Waterloo, the full horror of it could not be ignored.

But peace was finally declared, and that, despite the defeat of France, was a cause for celebration. No more war. No more bloodshed. No more death. It also meant that Celeste was finally free to travel. The commission from Sir Charles Trestain to paint his gardens for posterity before he had them substantially altered had come to her by chance. A fellow artist of her acquaintance, who had been the English baronet’s first choice, had been unable to accept due to other commitments and had recommended Celeste. She could not but think it was fated.

So here she was, in what she was only beginning to realise was a foreign country. Her command of the language had been the one and only piece of her heritage which her English mother had given her, though they had spoken it only when alone. As far as the world was concerned, Madame Marmion was as French as her husband.

Celeste stopped to remove a long strand of sticky willow which had become entangled in the flounce of her gown. The grass underfoot was lush and green, the air sweet-smelling and fresh, no trace of the southern dry heat of home—or rather the place she was raised, for a home was a place associated with love and affection, something which had been in very short supply in Cassis.

No matter, she had her own home now, her little studio apartment in Paris. The air in the city at this time of year was oppressive. Celeste took a deep breath of English air. She really was here. Soon, hopefully before the summer was over, she would have some answers. Though right at this moment, she wasn’t exactly clear how on earth she was going to set about finding them.

A gate at the end of the neglected Topiary Garden revealed a view of a lake. The brownish-green water looked cool and inviting. Frowning, deep in thought, it was only as she reached the water’s edge that Celeste noticed the lone swimmer. A man, scything his way through the water in a very odd manner, rather like a drunken fish. Coachman, gamekeeper, gardener or perhaps simply one of the local farmers taking advantage of the early-morning solitude? She could empathise with that. Solitude was a much-underrated virtue. Whoever he was, she ought to leave him to finish his illicit swim in Sir Charles’s lake. Had the roles been reversed she would have found the intrusion most offensive. And yet, instead of turning back the way she had come, Celeste stepped behind a bush and continued to watch, fascinated.

He was completely naked. The musculature of his torso was beautifully defined. His legs were long, well shaped, and equally well muscled. He would make a fascinating life study, though it would be a lie to say that it was purely with an artist’s eye that she observed him, peering as she did through the straggle of jagged hawthorn branches. Like his swimming, the man’s face was far from perfect. His nose was too strong, his brow too high, his eyes too intense and deeply sunk. He looked more fierce than handsome. No, not fierce, but there was a hardness to his features, giving him the air of a man who courted danger.

His swimming was becoming laboured. He slowed and stopped only a few yards from where she stood, staggering slightly as he found his footing. The water lapped around his waist. His chest heaved as he began to make his way towards the bank where his clothes were draped over a branch some distance away. It was too late for her to make her escape. She could only hold her breath, keep as still as possible and hope that he would not spot her.

His torso was deeply tanned. There was an odd puckered hollow in his right shoulder where the flesh appeared to have been scooped out. His entire right arm was distinctly paler than the rest of him, as if he had spent the summer wearing a shirt with one sleeve. A scar formed an inverted crescent on his left side, just under his rib cage. A man who liked to fight or one who was decidedly accident prone? He was panting, his chest expanding, his stomach contracting with each breath. His next step revealed the rest of his flat belly. The next, the top of his thighs, and a distinct line where his tan ended.

And then he stopped. He looked up to the sky, and Celeste’s breath caught in her throat as his face almost seemed to crumple, bearing such an expression of despair and grief that it twisted her heart before he dropped his head into his hands with a dry sob. His shoulders were heaving. Appalled, mortified to have witnessed such an intensely intimate moment, Celeste turned to flee. Her gown caught on the hawthorn briar, and before she could stifle it, an exclamation of dismay escaped her mouth.

He looked up. Their eyes met for one brief moment that seemed to last for an eternity. He looked both heartbreakingly vulnerable and volcanically angry. Celeste tore herself free of the thorns and fled.

* * *

Back in her room at Trestain Manor, Celeste could not get the image of the man’s tortured face out of her head. Nor her deep shame at having spied on him. She, of all people, should respect a person’s right to privacy, given how hard she defended her own. It took fifteen minutes for the colour to fade entirely from her cheeks and another fifteen before she was calm enough to face breakfast with her new patrons.

Praying that the man would not turn out to be one of Sir Charles’s footmen, she made her way down the stairs to the dining room where one of the austere servants indicated the morning repast was being taken. The very welcome aroma of coffee was overlaid with a stronger one of eggs and something meaty. Hoping that she would not be obliged to partake of either, Celeste opened the door and stopped dead in her tracks on the threshold.

The room was dark, for the windows were heavily curtained, and despite the white-painted ceiling, the overall impression was gloomy. An ornately carved and very highly polished walnut table took up most of the available space, around which were twelve throne-like chairs. Three were occupied. Sir Charles was seated at the top of the table. Lady Eleanor was on his right. And on his left sat another man. A man with damp hair, curling down over his collar. With a coat stretched across a pair of broad shoulders. Her stomach knotted.

‘Ah, Mademoiselle Marmion, I trust you slept well. Do join us.’

Sir Charles pushed his chair back and got to his feet. Celeste, her polite smile frozen, could not shift her gaze from the other guest. There was a kerchief knotted around his neck rather than a carefully tied cravat. He had shaved, but somehow he looked as if he had not.

‘Jack, this is Mademoiselle Marmion, the artist I was telling you about. She’s come all the way from Paris to capture our gardens for posterity before Eleanor’s landscaper gets his hands on them. Mademoiselle, do allow me to introduce you to my brother Jack, who is residing with us at present.’

Her first instinct, as he rose from his seat, was to run. He was smiling, a thin, cold smile, the sort of smile a man might bestow on a complete stranger, but she was not fooled. Celeste clutched the polished brass doorknob, for her knees had turned to jelly as the man from the lake crossed the room to greet her. The naked man from the lake who was Sir Charles’s brother. Mon Dieu, she had seen naked men before but what made her cheeks burn crimson was having witnessed that anguished look on his face. She had seen him naked, stripped bare in quite a different way. She felt as if she had violated some unspoken rule of trespass. Forcing herself to let go of the door handle, she met the cold, assessing look in his dark-brown eyes. What had possessed her to watch him? Why on earth had she not fled as soon as she’d seen him?