Полная версия:

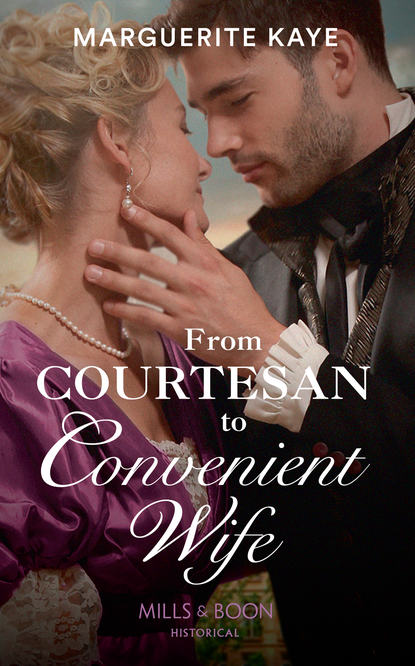

From Courtesan To Convenient Wife

Every woman wants to marry him

But what if he is already taken?

In this Matches Made in Scandal story, Jean-Luc Bauduin, Parisian society’s most eligible bachelor, is determined to take only a wife of his choosing. But until that day comes, he’ll ward off his admirers by hiring Lady Sophia Acton to wear his ring! The passion Jean-Luc shares with his convenient bride is enormously satisfying—until he discovers Sophia’s utterly scandalous past!

Matches Made in Scandal series:

From Governess to Countess

From Courtesan to Convenient Wife

More books in the series coming soon!

“This sweet and hot duet set at the holiday Brockmore Ball is the perfect pick-me-up. Kaye’s tender tale of redemption touches readers’ hearts.”

—RT Book Reviews on Scandal at the Christmas Ball

“Readers will be seduced by the passionate natures of the protagonists, and the fast-paced, thrilling adventure.”

—RT Book Reviews on The Harlot and the Sheikh

MARGUERITE KAYE writes hot historical romances from her home in cold and usually rainy Scotland, featuring Regency rakes, Highlanders and sheikhs. She has published almost fifty books and novellas. When she’s not writing she enjoys walking, cycling (but only on the level), gardening (but only what she can eat) and cooking. She also likes to knit and occasionally drink martinis (though not at the same time). Find out more on her website: margueritekaye.com.

Also by Marguerite Kaye

Scandal at the Midsummer BallScandal at the Christmas Ball

Comrades in Arms miniseries

The Soldier’s Dark SecretThe Soldier’s Rebel Lover

Hot Arabian Nights miniseries

The Widow and the SheikhSheikh’s Mail-Order BrideThe Harlot and the SheikhClaiming His Desert Princess

Matches Made in Scandal miniseries

From Governess to CountessFrom Courtesan to Convenient Wife

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk.

From Courtesan to Convenient Wife

Marguerite Kaye

www.millsandboon.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-474-07357-8

FROM COURTESAN TO CONVENIENT WIFE

© 2018 Marguerite Kaye

Published in Great Britain 2018

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk

For Paris, City of Light, city of romance and my favourite city in the world.

Je t’adore.

Contents

Cover

Back Cover Text

About the Author

Booklist

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Epilogue

Historical Note

Extract

About the Publisher

Prologue

London—May 1818

The house that was her destination was located on Upper Wimpole Street, on the very edge of what was considered to be respectable London. The woman known as The Procurer stepped down lightly from her barouche, ordering her coachman to wait until she had successfully secured entry, then to return for her in an hour. An hour, The Procurer knew from experience, was more than sufficient time to conclude her unique business. One way or another.

Number Fourteen was situated at the far end of the terrace. A shallow flight of steps led to the front door, but the entrance to the basement she sought was around the corner, on Devonshire Street. The Procurer descended the steep stairs cautiously. Despite the bright sunshine of the late spring morning, it was cool down here, dank and gloomy. The curtains were pulled tight over the single, dirty window. A fleck of paint fell from the door when she let the rusty knocker fall.

There was no reply. She rapped again, her eyes on the window, and was rewarded with the ripple of a curtain as the person behind it tried to peer out at her unobserved. She stood calmly, allowing herself to be surveyed, sadly accustomed to the reticence of the women she sought out to welcome unsolicited visitors. The reasons were manifold, but fear lay at the root of all of them.

The Procurer offered an escape route from their tribulations to those women whose particular skills or traits suited her current requirements. The exclusive temporary contracts she offered provided those who satisfied her criteria with the funds to make a fresh start, though what form that would take was always entirely up to them. The unique business she had established was very lucrative and satisfying too, on the whole, though there were occasions when The Procurer despaired of the tiny impact her altruism had, when set against the myriad injustices the world perpetrated against women. Today, however, she was in a positive mood. A new client, another extraordinary request to test her reputation for making the impossible possible. She had heard of Lady Sophia Acton’s spectacular fall from grace and had wondered, at the time, what had been the cause of it. Now, thanks to her spider’s web of contacts, she understood only too well. Her heart was touched—as much as that frozen organ could be, that is.

The Procurer gave a little nod to herself. She could not, she thought wryly, have designed a more appropriate task for the woman if she tried. Who had by now, she judged, had more than sufficient time to decide that her visitor was neither her landlady come to evict her, nor a lady of another sort come to harass her. It was time for Lady Sophia Acton to come out of hiding and return to the world. Albeit a very different one from that which she had previously inhabited.

The Procurer rapped on the door again, and this time her patience was rewarded, as she had known it would be. The woman who answered was tall and willowy, dressed in an outmoded gown of faded worsted which might originally have been either grey, blue or brown, and which was far too warm for the season. Her silver-blonde hair was fixed in a careless knot on top of her head from which long, wispy tendrils had escaped, framing her heart-shaped face. The wide-spaced eyes under her perfectly arched brows were extraordinary: almond-shaped, dark-lashed, the colour of lapis lazuli. There were dark shadows beneath them, and her skin had the fragility of one who slept little, but none the less Lady Sophia Acton was one of the most beautiful women The Procurer had ever encountered. It was an ethereal beauty, the type which would bring out the protective nature in some men, though more often than not, she thought darkly, the fine line between protection and exploitation would easily be crossed. Men would assume that Lady Sophia Acton’s fragile appearance equated to a fragile mind. Meeting the woman’s steady gaze, The Procurer thought very much otherwise.

‘Who are you? What do you want?’

The questions were perfunctory, the tone brusque. Lady Sophia had no time for social niceties, which suited The Procurer very well. She insinuated herself through the narrow opening, closing the door firmly behind her. ‘They call me The Procurer,’ she said. ‘And I want to put a business proposition to you.’

* * *

Sophia stared at the intruder in astonishment. This elegant, sophisticated woman was the elusive Procurer?

‘You are thinking that I look nothing like the creature of your imagination,’ her uninvited guest said. ‘Or perhaps I flatter myself. Perhaps you have not heard of me?’

‘I doubt there is anyone in London who has not heard of you, though how many have had the honour of making your acquaintance is a another matter. Your reputation for clandestine dealings goes before you.’

‘More of the great and the good use my services than you might imagine, or they would care to admit. Discretion, however, is what I insist upon above all. Whatever the outcome of our meeting today, Lady Sophia, I must have your promise that you will never talk of it.’

Sophia laughed at this. ‘Madam, you must be aware, for since you know my name you must also know of my notoriety, that there is no one who would listen even if I did. Those with a reputation to guard will cross the street to avoid me, while those who wish to further tarnish my reputation have no interest in my opinions on any subject.’

As she spoke, she led her visitor into the single room which had been her home for the last three weeks. The fourth home she had occupied in the months since her return from France, each one smaller, dingier and less genteel than the preceding one. It was only a matter of time before she was expelled from her current abode, for London, despite being a big city was in reality a small place, and London’s respectable landladies were even smaller-minded.

‘I am afraid that my accommodation does not run to a parlour,’ Sophia said, drawing out one of her two wooden chairs. ‘A woman in my position, it seems, has no right to comfort.’

‘No.’ The Procurer took the seat, pulling off her kid gloves and untying the ribbon of her poke bonnet. ‘A woman in your position, Lady Sophia, has very few options. I take it, from your humble surroundings, that you have decided against the obvious solution to your penury?’

‘You do not mince your words,’ Sophia replied, irked to feel her cheeks heating.

‘I find that it is better to be blunt, when conducting my business,’ The Procurer replied with a slight smile. ‘That way there is no room for misconceptions.’

Sophia took her own seat opposite. ‘Very well then, I will tell you that your assumption is correct. I have decided—I am determined—not to avail myself of the many lucrative offers I have received since my return to London. I was forced into that particular occupation for one very important reason. That reason...’

Despite herself, her throat constricted. Under the table, she curled her hands into fists. She swallowed hard. ‘That reason no longer exists. Therefore I will never—never—demean myself in that manner again, no matter how straitened my circumstances. So if you have come here in order to plead some man’s cause, then I’m afraid your journey has been a wasted one.’

Tears burned in her eyes, yet Sophia met her visitor’s gaze, defying her to offer sympathy. The Procurer merely nodded, looking thoughtful. ‘I have come here to plead on behalf of a man, but my proposal is not what you imagine. The services he requires of you are not of that nature. To be clear, you would be required to put on a performance, but quite explicitly not in the bedchamber. The role is a taxing one, but I think you will be perfect for it.’

Sophia laughed bitterly. ‘I am certainly adept at acting. The entire duration of my last—engagement—was a performance, nothing more.’

‘Something we have in common. I too have earned a living from performing. The Procurer you see before you is a façade, a persona I have been forced to adopt.’

Which remark begged any number of questions. Sophia, however, hesitated. There was empathy in the woman’s expression—but also a clear warning that some things were better left unspoken. Locking such things away in the dark recesses of memory, never to be exposed to scrutiny, was the best way to deal with them, as she knew only too well. Sophia uncurled her fists, clasping her hands together on the table. ‘I will be honest with you, Madam, and trust that your reputation for discretion is well earned. A woman in my position has, as you have pointed out, very few options, and even fewer resources. I do not know in what capacity I can be of service to you, but if I can do so without compromising what is left of my honour, then I will gladly consider your offer.’

Once again, The Procurer gave a little nod, though whether it was because she was satisfied with Sophia’s answer, or because Sophia had answered as she expected, there could be no telling. ‘What I can tell you is that the monetary reward for the fulfilment of your contract, should you choose to accept the commission, would be more than sufficient to secure your future, whatever form that might take.’

‘Frankly, I have no idea. At present, my only future plans are to survive day to day.’ But oh, Sophia thought, how much she would like to be able to discover for herself what the future might hold. Six months ago, bereft and utterly alone, raw with grief, she had been so low that she had no thought at all for the future. But life went on, and as it proceeded and her meagre funds dwindled, Sophia had not been able to look beyond the next month, the next week, the next day. Now, it seemed that a miracle might just be about to happen. The Procurer, that patroness of fallen women, was sitting opposite her and offering her a chance of redemption. ‘I have no idea what the future holds,’ Sophia repeated, with a slow smile, ‘but I do know that I want it, and that whatever it is, I want it to belong to me, and to no one else.’

‘Something else we have in common, then, Lady Sophia.’ This time The Procurer’s smile was warm. She reached over to touch Sophia’s hand. ‘I am aware of your circumstances, my dear, including the reason you were compelled to act as you did. You do not deserve to have paid such a high price, but sadly that is the way of our world. I cannot change that, but I do believe we can be of mutual benefit to each other. You do understand,’ she added, resuming her business-like tone, ‘that I am not offering you charity?’

‘And I am certain that you understand, for you seem to have investigated my background thoroughly, that I would not accept charity even if it was offered,’ Sophia retorted.

‘Then indeed, we understand each other very well.’

‘Not quite that well, Madam. I am as yet completely in the dark regarding this role you think me so perfectly suited for. What is it that you require me to do?’

But The Procurer held up her hand. ‘A few non-negotiable ground rules first, Lady Sophia. I will guarantee you complete anonymity. My client has no right to know your personal history other than that which is pertinent to the assignment or which you yourself choose to divulge. In return, you will give him your unswerving loyalty. We will discuss your terms shortly, but you must know that you will be paid only upon successful completion of your assignment. Half-measures will not be rewarded. If you leave before the task is completed, you will return to England without remuneration.’

‘Return to England?’ Sophia repeated, somewhat dazed. ‘You require me to travel abroad?’

‘All in good time. I must have your word, Lady Sophia.’

‘You have it, Madam, rest assured. Now, will you put me out of my misery and explain what it is that is required of me and who this mysterious client of yours is.’

Chapter One

Paris—ten days later

The carriage which had transported Sophia all the way from Calais drew to a halt in front of a stone portal surmounted by a pediment on which carved lions’ heads roared imperiously. The gateway’s huge double doors were closed. Was this her final destination? They had passed through one of the entrance gates to the city some time ago, following the course of the bustling River Seine, which allowed her to catch a glimpse of the imposing edifice which she assumed was Notre Dame cathedral. Despite this, Sophia still couldn’t quite believe she was actually here, in Paris.

The days since her momentous meeting with The Procurer had passed in a blur of activity as her papers were organised, her travel arrangements confirmed, and her packing completed. Not that she’d had much packing to do. The costumes required for her to carry out her new duties would be provided by the man who presumably awaited her on the other side of those doors. The man to whom she was bound for the duration of the contract. The shudder of revulsion was instinctive and quickly repressed. This contract was a world away from the last, less formal and much more distasteful, one she had reluctantly entered into to, she reminded herself. The Procurer had promised her that her stipulated terms would be honoured. Though she must do his bidding in public, this man had no right to any part of her, mind or body, in private. So it was not the same. This man was not Sir Richard Hopkins. The services he was paying for were radically different in nature. And when it was over, she would be truly free for the first time in her life.

The butterflies which had been slowly building in her stomach from early this morning, when she had quit the last of the posting houses to embark on the final leg of her journey, began to flutter wildly as Sophia saw the huge doors swing inward and one of the grooms opened the carriage door and folded down the steps. Gathering up the folds of her travelling gown she descended, glad of his steadying hand, for her nervous anticipation was palpable.

‘Monsieur awaits you, madame,’ the servant informed her.

‘Merci,’ Sophia replied, summoning up what she hoped was an appropriately eager smile, thanking the man in his own language for taking care of her during the journey. The servant bowed. She heard the carriage door slam, the clop of the horses’ hooves on the cobblestones as it headed for the stables.

Bracing herself, Sophia prepared to make her entrance. The hôtel particulier which she assumed was to be her temporary home was beautiful. Built around the courtyard in which she now stood, there were three wings, each with the steeply pitched roof and tall windows in the French baroque style, the walls softened with a cladding of ivy. The courtyard was laid out with two parterres of box hedging cut into an elaborate swirling design which, seen from above, she suspected, would form some sort of crest. The main entrance to the hôtel was on her left-hand side. At the top of a set of shallow steps, the open doorway was guarded by a winged marble statue. And standing beside the statue, a man.

Late afternoon sunlight glinted down, dazzling her eyes. She had the absurd idea that as long as she stood rooted to the spot, time would stand still. Just long enough for her to quell her fears, which were hardly unjustified, given her experience. Men wanted but one thing from her. Despite The Procurer’s promises and reassurances, until she could determine for herself that this man was different and posed no threat to her, she would, quite rightly, be on her guard.

Though she must not appear so. Sophia steeled herself. The future, as she had discovered to her cost, did not take care of itself. This was her chance to forge her own. Though she had assumed her new persona in Calais, now she must play it in earnest. She had coped with much worse, performed a far more taxing role. She could do this! Fixing a demure smile on her face for the benefit of anyone watching from the myriad of windows, she made her way across the paved courtyard.

The man she approached was tall, sombrely dressed, the plain clothes drawing attention to an impressive physique. Black hair. Very tanned skin. Younger than she had anticipated for a man so ostentatiously wealthy, no more than thirty-five, perhaps less. As she reached the bottom of the steps, he smiled, and Sophia faltered. He was a veritable Adonis. She felt her skin prickle with heat, an unfamiliar sensation which she attributed to nerves, as he descended to greet her.

Jean-Luc Bauduin, The Procurer’s client and the reason she was here, took her hand, making a show of raising it to his lips, though he kissed the air above her fingertips. ‘You have arrived at last,’ he said in softly accented English. ‘You can have no idea how eagerly I have been anticipating your arrival. Welcome to Paris, Madame Bauduin. It is a relief beyond words to finally meet my new wife.’

* * *

Jean-Luc led the Englishwoman through the tall doors opening on to the terrace, straight into the privacy of the morning room. ‘We may speak freely here,’ he informed her. ‘Tomorrow, we will play out the charade of formal introductions to the household. For now, I think it would be prudent for us to become a little better acquainted, given that you are supposed to be my beloved wife.’ Thinking that it would take a while to accustom himself to this bizarre notion, he motioned for her to take a seat. ‘You must be tired after your long journey. Will you take some tea?’

Though he spoke in English, she answered him in perfect French. ‘Thank you, it has indeed been a long day, that would be delightful.’

‘Your command of our language is an unexpected bonus,’ Jean-Luc said, ‘but when we are alone, I am happy to converse in yours.’

‘You certainly speak it fluently, if I may return the compliment,’ she said, removing her bonnet and gloves.

‘I am required to visit London frequently on matters of business.’

The service was already set out on the table before her, the silver kettle boiling on the spirit stove. His wife—mon Dieu, the woman who was to play his wife!—set about the ritual which the English were so fond of with alacrity, clearly eager to imbibe. In this one assumption, at least, he had been correct.

Jean-Luc took his seat opposite, studying her as she busied herself making tea. Despite the flurry of communications he’d had with The Procurer, there was a part of him that had not believed the woman would be able to deliver someone who perfectly matched his precise requirements, yet here was the living, breathing proof that she had. In fact, in appearance at least, the candidate she had selected had wildly exceeded his expectations. Not that her allure was the salient factor. Finally, after all these weeks of uncertainty and creeping doubt, he could act. Recent events had threatened to turn his world upside down. Now, he could set it to rights again, and the arrival of this woman, his faux wife, was the first significant step in his plan.