Полная версия:

Tigana

GUY GAVRIEL KAY

Tigana

For my brothers, Jeffrey and Rex

Contents

Title Page

A Note on Pronunciation

Prologue

Part One

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Part Two

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Part Three

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Part Four

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Part Five

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Guy Gavriel Kay

Copyright

About the Publisher

A Note on Pronunciation

For the assistance of those to whom such things are of importance, I should perhaps note that most of the proper names in this novel should be pronounced according to the rules of the Italian language. Thus, for example, all final vowels are sounded: Corte has two syllables, Sinave and Forese have three. Chiara has the same hard initial sound as chianti but Certando will begin with the same sound as chair or child.

All that you held most dear you will put by

and leave behind you; and this is the arrow

the longbow of your exile first lets fly.

You will come to know how bitter as salt and stone

is the bread of others, how hard the way that goes

up and down stairs that never are your own.

—Dante, The Paradiso

What can a flame remember? If it remembers a little less than is necessary, it goes out; if it remembers a little more than is necessary, it goes out. If only it could teach us, while it burns, to remember correctly.

—George Seferis, ‘Stratis the Sailor

Describes a Man’

Prologue

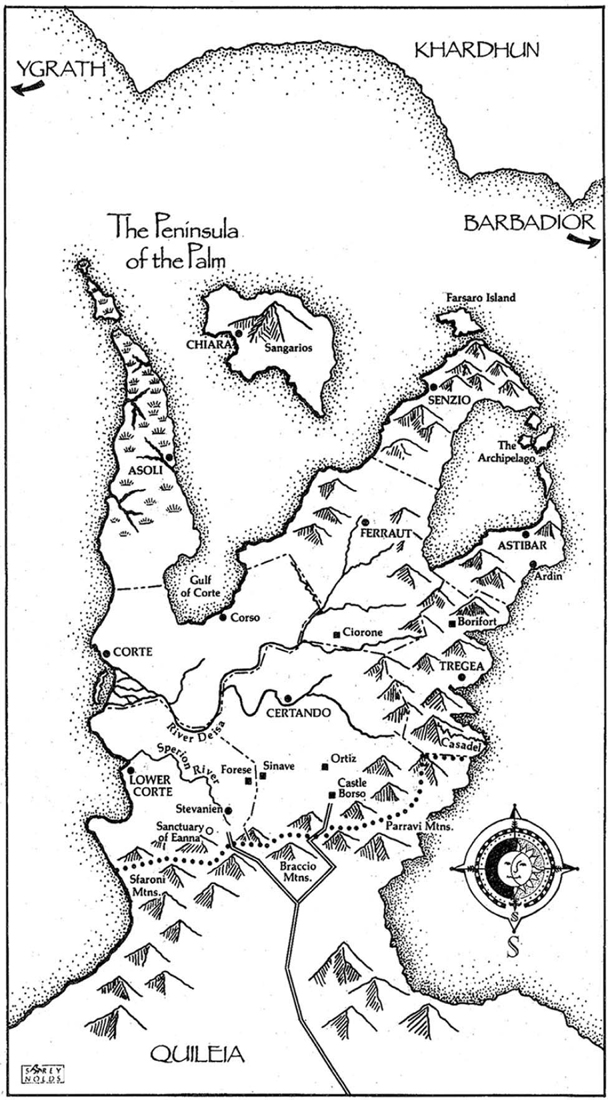

Both moons were high, dimming the light of all but the brightest stars. The campfires burned on either side of the river, stretching away into the night. Quietly flowing, the Deisa caught the moonlight and the orange of the nearer fires and cast them back in wavery, sinuous ripples. And all the lines of light led to his eyes, to where he was sitting on the riverbank, hands about his knees, thinking about dying and the life he’d lived.

There was a glory to the night, Saevar thought, breathing deeply of the mild summer air, smelling water and water flowers and grass, watching the reflection of blue moonlight and silver on the river, hearing the Deisa’s murmurous flow and the distant singing from around the fires. There was singing on the other side of the river too, he noted, listening to the enemy soldiers north of them. It was curiously hard to impute any absolute sense of evil to those harmonizing voices, or to hate them quite as blindly as being a soldier seemed to require. He wasn’t really a soldier, though, and he had never been good at hating.

He couldn’t actually see any figures moving in the grass across the river, but he could see the fires and it wasn’t hard to judge how many more of them lay north of the Deisa than there were here behind him, where his people waited for the dawn.

Almost certainly their last. He had no illusions; none of them did. Not since the battle at this same river five days ago. All they had was courage, and a leader whose defiant gallantry was almost matched by the two young sons who were here with him.

They were beautiful boys, both of them. Saevar regretted that he had never had the chance to sculpt either of them. The Prince he had done of course, many times. The Prince called him a friend. It could not be said, Saevar thought, that he had lived a useless or an empty life. He’d had his art, the joy of it and the spur, and had lived to see it praised by the great ones of his province, indeed of the whole peninsula.

And he’d known love, as well. He thought of his wife and then of his own two children. The daughter whose eyes had taught him part of the meaning of life on the day she’d been born fifteen years ago. And his son, too young by a year to have been allowed to come north to war. Saevar remembered the look on the boy’s face when they had parted. He supposed that much the same expression had been in his own eyes. He’d embraced both children, and then he’d held his wife for a long time, in silence; all the words had been spoken many times through all the years. Then he’d turned, quickly, so they would not see his tears, and mounted his horse, unwontedly awkward with a sword on his hip, and had ridden away with his Prince to war against those who had come upon them from over the sea.

He heard a light tread, behind him and to his left, from where the campfires were burning and voices were threading in song to the tune a syrenya played. He turned to the sound.

‘Be careful,’ he called softly. ‘Unless you want to trip over a sculptor.’

‘Saevar?’ an amused voice murmured. A voice he knew well.

‘It is, my lord Prince,’ he replied. ‘Can you remember a night so beautiful?’

Valentin walked over—there was more than enough light by which to see—and sank neatly down on the grass beside him. ‘Not readily,’ he agreed. ‘Can you see? Vidomni’s waxing matches Ilarion’s wane. The two moons together would make one whole.’

‘A strange whole that would be,’ Saevar said.

‘’Tis a strange night.’

‘Is it? Is the night changed by what we do down here? We mortal men in our folly?’

‘The way we see it is,’ Valentin said softly, his quick mind engaged by the question. ‘The beauty we find is shaped, at least in part, by what we know the morning will bring.’

‘What will it bring, my lord?’ Saevar asked, before he could stop himself. Half hoping, he realized, as a child hopes, that his dark-haired Prince of grace and pride would have an answer yet to what lay waiting across the river. An answer to all those Ygrathen voices and all the Ygrathen fires burning north of them. An answer, most of all, to the terrible King of Ygrath and his sorcery, and the hatred that he at least would have no trouble summoning tomorrow.

Valentin was silent, looking out at the river. Overhead Saevar saw a star fall, angling across the sky west of them to plunge, most likely, into the wideness of the sea. He was regretting the question; this was no time to be putting a burden of false certitude upon the Prince.

Just as he was about to apologize, Valentin spoke, his voice measured and low, so as not to carry beyond their small circle of dark.

‘I have been walking among the fires, and Corsin and Loredan have been doing the same, offering comfort and hope and such laughter as we can bring to ease men into sleep. There is not much else we can do.’

‘They are good boys, both of them,’ Saevar offered. ‘I was thinking that I’ve never sculpted either of them.’

‘I’m sorry for that,’ Valentin said. ‘If anything lasts for any length of time after us it will be art such as yours. Our books and music, Orsaria’s green and white tower in Avalle.’ He paused, and returned to his original thought. ‘They are brave boys. They are also sixteen and nineteen, and if I could have I would have left them behind with their brother . . . and your son.’

It was one of the reasons Saevar loved him: that Valentin would remember his own boy, and think of him with the youngest prince, even now, at such a time as this.

To the east and a little behind them, away from the fires, a trialla suddenly began to sing and both men fell silent, listening to the silver of that sound. Saevar’s heart was suddenly full, he was afraid that he might shame himself with tears, that they would be mistaken for fear.

Valentin said, ‘But I haven’t answered your question, old friend. Truth seems easier here in the dark, away from the fires and all the need I have been seeing there. Saevar, I am so sorry, but the truth is that almost all of the morning’s blood will be ours, and I am afraid it will be all of ours. Forgive me.’

‘There is nothing to forgive,’ Saevar said quickly, and as firmly as he could. ‘This is not a war of your making, nor one you could avoid or undo. And besides, I may not be a soldier but I hope I am not a fool. It was an idle question: I can see the answer for myself, my lord. In the fires across the river.’

‘And the sorcery,’ Valentin added quietly. ‘More that, than the fires. We could beat back greater numbers, even weary and wounded as we are from last week’s battle. But Brandin’s magic is with them now. The lion has come himself, not the cub, and because the cub is dead there must be blood for the morning sun. Should I have surrendered last week? To the boy?’

Saevar turned to look at the Prince in the blended moonlight, disbelieving. He was speechless for a moment, then found his voice. ‘I would have gone home from that surrender,’ he said, with resolution, ‘and walked into the Palace by the Sea, and smashed every sculpture I ever made of you.’

A second later he heard an odd sound. It took him a moment to realize that Valentin was laughing, because it wasn’t laughter like any Saevar had ever heard.

‘Oh, my friend,’ the Prince said, at length, ‘I think I knew you would say that. Oh, our pride. Our terrible pride. Will they remember that most about us, do you think, after we are gone?’

‘Perhaps,’ Saevar said. ‘But they will remember. The one thing we know with certainty is that they will remember us. Here in the peninsula, and in Ygrath, and Quileia, even west over the sea, in Barbadior and its Empire. We will leave a name.’

‘And we leave our children,’ Valentin said. ‘The younger ones. Sons and daughters who will remember us. Babes in arms our wives and grandfathers will teach when they grow up to know the story of the River Deisa, what happened here, and, even more—what we were in this province before the fall. Brandin of Ygrath can destroy us tomorrow, he can overrun our home, but he cannot take away our name, or the memory of what we have been.’

‘He cannot,’ Saevar echoed, feeling an odd, unexpected lift to his heart. ‘I am sure that you are right. We are not the last free generation. There will be ripples of tomorrow that run down all the years. Our children’s children will remember us, and will not lie tamely under the yoke.’

‘And if any of them seem inclined to,’ Valentin added in a different tone, ‘there will be the children or grandchildren of a certain sculptor who will smash their heads for them, of stone or otherwise.’

Saevar smiled in the darkness. He wanted to laugh, but it was not in him just then. ‘I hope so, my lord, if the goddesses and the god allow. Thank you. Thank you for saying that.’

‘No thanks, Saevar. Not between us and not this night. The Triad guard and shelter you tomorrow, and after, and guard and shelter all that you have loved.’

Saevar swallowed. ‘You know you are a part of that, my lord. A part of what I have loved.’

Valentin did not reply. Only, after a moment, he leaned forward and kissed Saevar upon the brow. Then he held up a hand and the sculptor, his eyes blurring, raised his own hand and touched his Prince’s palm to palm in farewell. Valentin rose and was gone, a shadow in moonlight, back towards the fires of his army.

The singing seemed to have stopped, on both sides of the river. It was very late. Saevar knew he should be making his own way back and settling down for a few snatched hours of sleep. It was hard to leave though, to rise and surrender the perfect beauty of this last night. The river, the moons, the arch of stars, the fireflies and all the fires.

In the end he decided to stay there by the water. He sat alone in the summer darkness on the banks of the River Deisa, with his strong hands loosely clasped about his knees. He watched the two moons set and all the fires slowly die and he thought of his wife and children and the life’s work of his hands that would live after him, and the trialla sang for him all night long.

Part One

A Blade in the Soul

Chapter I

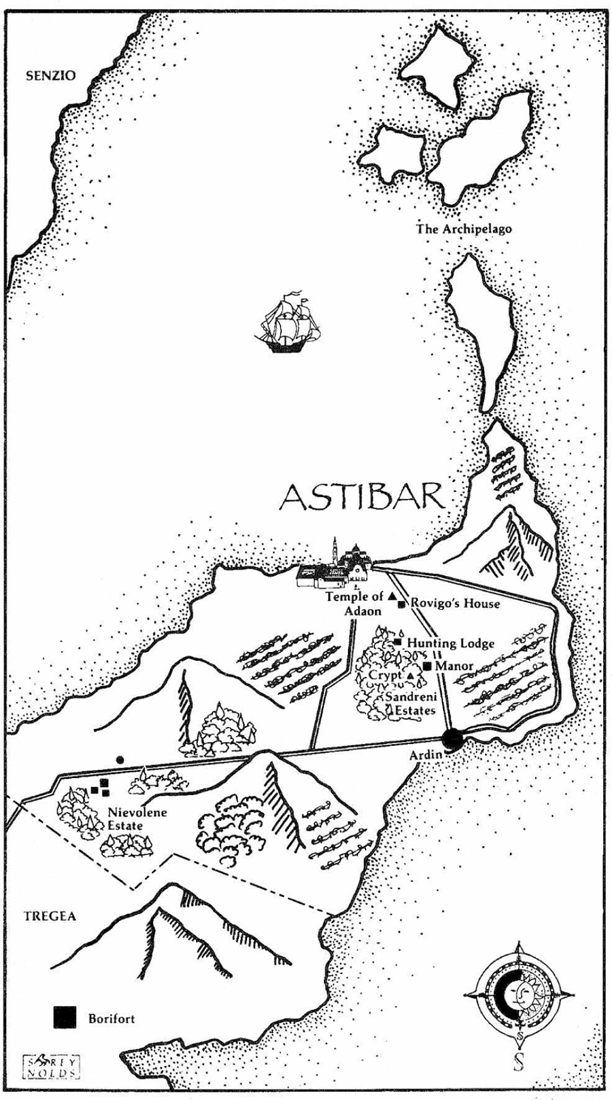

In the autumn season of the wine, word went forth from among the cypresses and olives and the laden vines of his country estate that Sandre, Duke of Astibar, once ruler of that city and its province, had drawn the last bitter breath of his exile and age and died.

No servants of the Triad were by his side to speak their rituals at his end. Not the white-robed priests of Eanna, nor those of dark Morian of Portals, nor the priestesses of Adaon, the god.

There was no particular surprise in Astibar town when these tidings came with the word of the Duke’s passing. Exiled Sandre’s rage at the Triad and its clergy through the last eighteen years of his life was far from being a secret. And impiety had never been a thing from which Sandre d’Astibar, even in the days of his power, had shied away.

The city was overflowing with people from the outlying distrada and far beyond on the eve of the Festival of Vines. In the crowded taverns and khav rooms truths and lies about the Duke were traded back and forth like wool and spice by folk who had never seen his face and who would have once paled with justifiable terror at a summons to the Ducal court in Astibar.

All his days Duke Sandre had occasioned talk and speculation through the whole of the peninsula men called the Palm—and there was nothing to alter that fact at the time of his dying, for all that Alberico of Barbadior had come with an army from that Empire overseas and exiled Sandre into the distrada eighteen years before. When power is gone the memory of power lingers.

Perhaps because of this, and certainly because he tended to be cautious and circumspect in all his ways, Alberico, who held four of the nine provinces in an iron grip and was vying with Brandin of Ygrath for the ninth, acted with a precise regard for protocol.

By noon of the day the Duke died, a messenger from Alberico was seen to have ridden out by the eastern gate of the city. A messenger bearing the blue-silver banner of mourning and carrying, no one doubted, carefully chosen words of condolence to Sandre’s children and grandchildren now gathered at their broad estate seven miles beyond the walls.

In The Paelion, the khav room where the wittier sort were gathering that season, it was cynically observed that the Tyrant would have been more likely to send a company of his own Barbadian mercenaries—not just a single message-bearer—were the living Sandreni not such a feckless lot. Before the appreciative, eye-to-who-might-be-listening ripple of amusement at that had quite died away, one itinerant musician—there were scores of them in Astibar that week—had offered to wager all he might earn in the three days to come, that from the island of Chiara would arrive condolences in verse before the Festival was over.

‘Too rich an opportunity,’ the rash newcomer explained, cradling a steaming mug of khav laced with one of the dozen or so liqueurs that lined the shelves behind the bar of The Paelion. ‘Brandin will be incapable of letting slip a chance like this to remind Alberico—and the rest of us—that though the two of them have divided our peninsula the share of art and learning is quite tilted west towards Chiara. Mark my words—and wager who will—we’ll have a knottily rhymed verse from stout Doarde or some silly acrostic thing of Camena’s to puzzle out, with “Sandre” spelled six ways and backwards, before the music stops in Astibar three days from now.’

There was laughter, though again it was guarded, even on the eve of the Festival, when a long tradition that Alberico of Barbadior had circumspectly indulged allowed more licence than elsewhere in the year. A few men with heads for figures did some rapid calculations of sailing-time and the chances of the autumn seas north of Senzio province and down through the Archipelago, and the musician found his wager quickly covered and recorded on the slate on the wall of The Paelion that existed for just such a purpose in a city prone to gambling.

But shortly after that all wagers and mocking chatter were forgotten. Someone in a steep cap with a curled feather flung open the doors of the khav room, shouted for attention, and when he had it, reported that the Tyrant’s messenger had just been seen returning through the same eastern gate from which he had so lately sallied forth. That the messenger was riding at an appreciably greater speed than hitherto, and that, not three miles to his rear was the funerary procession of Duke Sandre d’Astibar being brought by his last request to lie a night and a day in state in the city he once had ruled.

In The Paelion the reaction was immediate and predictable: men began shouting fiercely to be heard over the din they themselves were causing. Noise and politics and the anticipated pleasures of the Festival made for a thirsty afternoon. So brisk was his trade that the excitable proprietor of The Paelion began inadvertently serving full measures of liqueur in the laced khavs being ordered in profusion. His wife, of more phlegmatic disposition, continued to short-measure all her patrons with benevolent lack of favouritism.

‘They’ll be turned back!’ young Adreano the poet cried, decisively banging down his mug and sloshing hot khav over the dark oak table of The Paelion’s largest booth. ‘Alberico will never allow it!’ There were growls of assent from his friends and the hangers-on who always clustered about this particular table.

Adreano stole a glance at the travelling musician who’d made the brash wager on Brandin of Ygrath and his court poets on Chiara. The fellow, looking highly amused, his eyebrows quizzically arched, leaned back comfortably in the chair he had brazenly pulled up to the booth some time ago. Adreano felt seriously offended by the man, and didn’t know whether his umbrage had been more aroused by the musician’s so-casual assertion of Chiara’s pre-eminence in culture, or by his flippant dismissal of the great Camena di Chiara whom Adreano had been assiduously imitating for the past half-year: both in the fashion of his verses and the wearing of a three-layered cloak by day and night.

Adreano was intelligent enough to be aware that there might be a contradiction inherent in these twinned sources of ire, but he was also young enough and had drunk a more than sufficient quantity of khav laced with Senzian brandy, for that awareness to remain well below the level of his conscious thoughts.

Which remained focused on this presumptuous rustic. The man had evidently journeyed into the city to saw or pluck for three days at some country instrument or other in exchange for a handful of astins to squander at the Festival. How did such a fellow dare sail into the most fashionable khav room in the Eastern Palm and thump his rural behind down onto a chair at the most coveted table in that room? Adreano still carried painfully vivid memories of the long month it had taken him—even after his first verses had appeared in print—to circle warily closer, flinching inwardly at apprehended rebuffs, before he became a member of the select and well-known circle that had a claim upon this booth.

He found himself actually hoping that the musician would presume to contradict his opinion: he had a choice couplet already prepared, about rabble of the road spewing views on their betters in the company of their betters.

As if on cue to that thought, the fellow slumped even more comfortably back in his chair, stroked a prematurely silvered temple with a long finger and said, directly to Adreano, ‘This seems to be my afternoon for wagers. I’ll risk everything I’m about to win on the other matter that Alberico is too cautious to ruffle the mood of the Festival over this. There are too many people in Astibar right now and spirits are running too high—even with the half-measured drinks they serve in here to people who should know better.’

He grinned, to take some of the sting from the last words. ‘Far better for the Tyrant to be gracious,’ he went on. ‘To lay his old enemy ceremoniously to rest once and for all, and then offer thanks to whatever gods his Emperor overseas is ordering the Barbadians to worship these days. Thanks and offerings, for he can be certain that the geldings Sandre’s left behind will be pleasingly swift to abandon the unfashionable pursuit of freedom that Sandre stood for in ungelded Astibar.’

By the end of his speech he was not smiling, nor did the wide-set grey eyes look away from Adreano’s own.

And here, for the first time, were truly dangerous words. Softly spoken, but they had been heard by everyone in the booth, and suddenly their corner of The Paelion became an unnaturally quiet space amid the unchecked din everywhere else in the room. Adreano’s derisive couplet, so swiftly composed, now seemed trivial and inappropriate in his own ears. He said nothing, his heart beating curiously fast. With some effort he kept his gaze on the musician.

Who added, the crooked smile returning, ‘Do we have a wager, friend?’

Parrying for time while he rapidly began calculating how many astins he could lay palms on by cornering certain friends, Adreano said, ‘Would you care to enlighten us as to why a farmer from the distrada is so free with his money to come and with his views on matters such as this?’

The other’s smile widened, showing even white teeth. ‘I’m no farmer,’ he protested genially, ‘nor from your distrada either. I’m a shepherd from up in the south Tregea mountains and I’ll tell you a thing.’ The grey eyes swung round, amused, to include the entire booth. ‘A flock of sheep will teach you more about men than some of us would like to think, and goats . . . well, goats will do better than the priests of Morian to make you a philosopher, especially if you’re out on a mountain in rain chasing after them with thunder and night coming on together.’

There was genuine laughter around the booth, abetted somewhat by the release of tension. Adreano tried unsuccessfully to keep his own expression sternly repressive.

‘Have we a wager?’ the shepherd asked one more time, his manner friendly and relaxed.

Adreano was saved the need to reply, and several of his friends were spared an amount of grief and lost astins by the arrival, even more precipitous than that of the feather-hatted tale-bearer, of Nerone the painter.

‘Alberico’s given permission!’ he trumpeted over the roar in The Paelion. ‘He’s just decreed that Sandre’s exile ended when he died. The Duke’s to lie in state tomorrow morning at the old Sandreni Palace and have a full-honours funeral with all nine of the rites! Provided’—he paused dramatically—‘provided the clergy of the Triad are allowed in to do their part of it.’

The implications of all this were simply too large for Adreano to brood much upon his own loss of face— young, overly impetuous poets had that happen to them every second hour or so. But these—these were great events! His gaze, for some reason, returned to the shepherd. The man’s expression was mild and interested, but certainly not triumphant.

‘Ah well,’ the fellow said with a rueful shake of his head, ‘I suppose being right will have to compensate me for being poor—the story of my life, I fear.’

Adreano laughed. He clapped the portly, breathless Nerone on the back and shifted over to make room for the painter. ‘Eanna bless us both,’ he said to him. ‘You just saved yourself more astins than you have. I would have touched you to make a wager I would have just lost with your tidings.’