Полная версия:

Lord of Emperors

Lord of Emperors

Book Two of The Sarantine Mosaic

GUY GAVRIEL KAY

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

Copyright © Guy Gavriel Kay 2000

Guy Gavriel Kay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007342099

Ebook Edition © 2011 ISBN: 9780007352074

Version: 2014-12-03

Dedication

For Sam and Matthew, ‘the singing-masters of my soul.’

This belongs to them, beginning and end.

Epigraph

Turning and turning in a widening gyre . . .

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

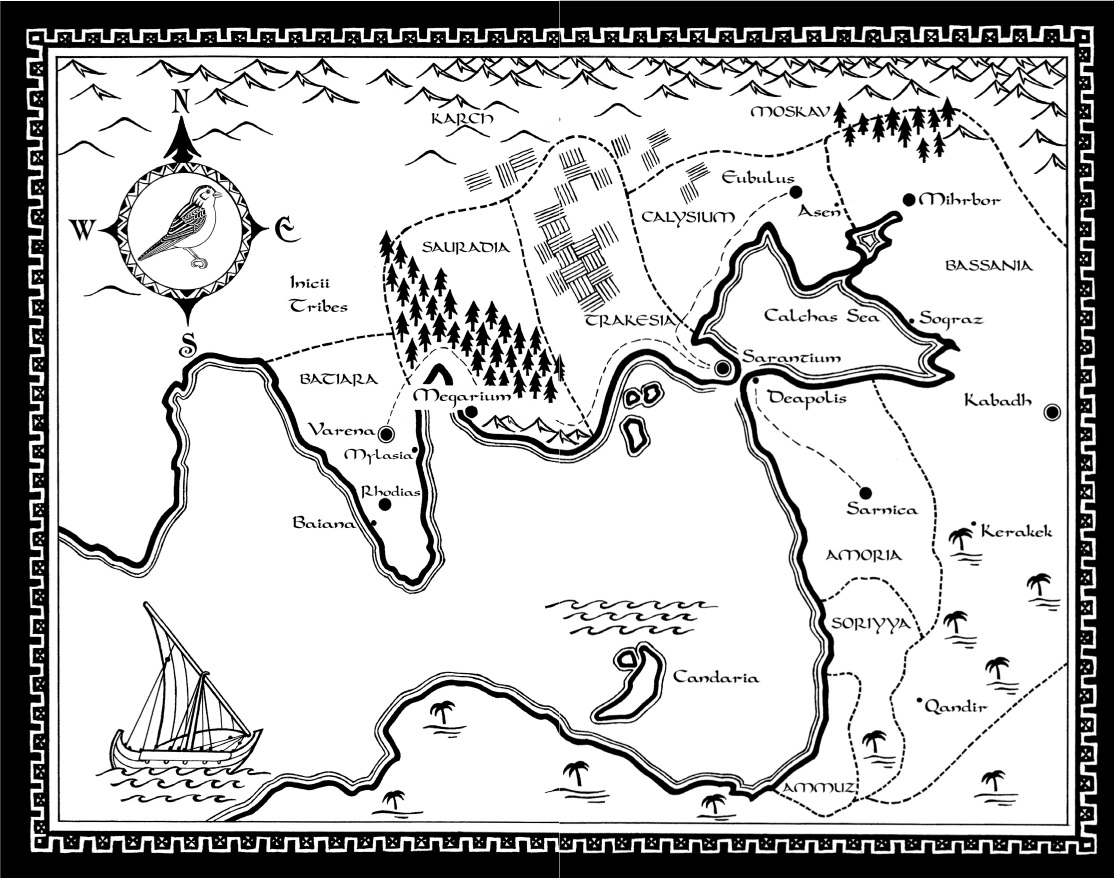

Map

Part One: Kingdoms of Light and Dark

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Part Two: The Ninth Driver

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Epilogue

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Map

PART ONE

KINGDOMS OF LIGHT AND DARK

Chapter I

Amid the first hard winds of winter, the King of Kings of Bassania, Shirvan the Great, Brother to the Sun and Moons, Sword of Perun, Scourge of Black Azal, left his walled city of Kabadh and journeyed south and west with much of his court to examine the state of his fortifications in that part of the lands he ruled, to sacrifice at the ancient Holy Fire of the priestly caste, and to hunt lions in the desert. On the first morning of the first hunt he was shot just below the collarbone.

The arrow lodged deep and no man there among the sands dared try to pull it out. The King of Kings was taken by litter to the nearby fortress of Kerakek. It was feared that he would die.

Hunting accidents were common. The Bassanid court had its share of those enthusiastic and erratic with their bows. This truth made the possibility of undetected assassination high. Shirvan would not be the first king to have been murdered in the tumult of a royal hunt.

As a precaution, Mazendar, who was vizier to Shirvan, ordered the king’s three eldest sons, who had journeyed south with him, to be placed under observation. A useful phrase masking the truth: they were detained under guard in Kerakek. At the same time the vizier sent riders back to Kabadh to order the similar detention of their mothers in the palace. Great Shirvan had ruled Bassania for twenty-seven years that winter. His eagle’s gaze was clear, his plaited beard still black, no hint of grey age descending upon him. Impatience among grown sons was to be expected, as were lethal intrigues among the royal wives.

Ordinary men might look to find joy among their children, sustenance and comfort in their households. The existence of the King of Kings was not as that of other mortals. His were the burdens of godhood and lordship—and Azal the Enemy was never far away and always at work.

In Kerakek, the three royal physicians who had made the journey south with the court were summoned to the room where men had laid the Great King down upon his bed. One by one each of them examined the wound and the arrow. They touched the skin around the wound, tried to wiggle the embedded shaft. They paled at what they found. The arrows used to hunt lions were the heaviest known. If the feathers were now to be broken off and the shaft pushed down through the chest and out, the internal damage would be prodigious, deadly. And the arrow could not be pulled back, so deeply had it penetrated, so broad was the iron flange of the arrowhead. Whoever tried to pull it would rip through the king’s flesh, tearing the mortal life from him with his blood.

Had any other patient been shown to them in this state, the physicians would all have spoken the words of formal withdrawal: With this affliction I will not contend. No blame for ensuing death could attach to them when they did so.

It was not, of course, permitted to say this when the afflicted person was the king.

With the Brother to the Sun and Moons the physicians were compelled to accept the duty of treatment, to do battle with whatever they found and set about healing the injury or illness. If an accepted patient died, blame fell to the doctor’s name, as was proper. In the case of an ordinary man or woman, fines were administered as compensation to the family.

Burning of the physicians alive on the Great King’s funeral pyre could be anticipated in this case.

Those who were offered a medical position at the court, with the wealth and renown that came with it, knew this very well. Had the king died in the desert, his physicians—the three in this room and those who had remained in Kabadh—would have been numbered among the honoured mourners of the priestly caste at his rites before the Holy Fire. Now it was otherwise.

There ensued a whispered colloquy among the doctors by the window. They had all been taught by their own masters—long ago, in each case—the importance of an unruffled mien in the presence of the patient. This calm demeanour was, in the current circumstances, imperfectly observed. When one’s own life lies embedded—like a bloodied arrow shaft—in the flux of the moment, gravity and poise become difficult to attain.

One by one, in order of seniority, the three of them approached the man on the bed a second time. One by one they abased themselves, rose, touched the black arrow again, the king’s wrist, his forehead, looked into his eyes, which were open and enraged. One by one, tremulously, they said, as they had to say, ‘With this affliction I will contend.’

When the third physician had spoken these words, and then stepped back, uncertainly, there was a silence in the room, though ten men were gathered amid the lamps and the guttering flame of the fire. Outside, the wind had begun to blow.

In that stillness the deep voice of Shirvan himself was heard, low but distinct, godlike. The King of Kings said, ‘They can do nothing. It is in their faces. Their mouths are dry as sand with fear, their thoughts are as blown sand. They have no idea what to do. Take the three of them away from us and kill them. They are unworthy. Do this. Find our son Damnazes and have him staked out in the desert to be devoured by beasts. His mother is to be given to the palace slaves in Kabadh for their pleasure. Do this. Then go to our son Murash and have him brought here to us.’ Shirvan paused to draw breath, to push away the humiliating weakness of pain. ‘Bring also to us a priest with an ember of the Holy Flame. It seems we are to die in Kerakek. All that happens is by the divine will of Perun. Anahita waits for all of us. It has been written and it is being written. Do these things, Mazendar.’

‘No physician at all, my great lord?’ said the small, plump vizier, dry-voiced, dry-eyed.

‘In Kerakek?’ said the King of Kings, his voice bitter, enraged. ‘In this desert? Think where we are.’ There was blood welling as he spoke, from where the arrow lay in him, the shaft smeared black, fletched with black feathers. The king’s beard was stained with his own dark blood.

The vizier bowed his head. Men moved to usher the three condemned physicians from the room. They offered no protest, no resistance. The sun was past its highest point by then, beginning to set, on a winter’s day in Bassania in a remote fortress near the sands. Time was moving; what was to be had long ago been written.

Men find courage sometimes, unexpectedly, surprising themselves, changing the course of their own lives and times. The man who sank to his knees by the bed, pressing his head to the carpeted floor, was the military commander of the fortress of Kerakek. Wisdom, discretion, self- preservation all demanded he keep silent among the sleek, dangerous men of the court that day. Afterwards he could not have said why he did speak. He would tremble as with a fever, remembering, and drink an excess of wine, even on a day of abstinence.

‘My king,’ he said in the firelit chamber, ‘we have a much-travelled physician here, in the village below the fortress. We might summon him?’

The Great King’s gaze seemed already to be in another place, with Perun and the Lady, beyond the confines and small concerns of mortal life. He said, ‘Why kill another man?’

It was told of Shirvan, written on parchment and engraved on tablets of stone, that no man more merciful and compassionate, more imbued with the spirit of the goddess Anahita, had ever sat the throne in Kabadh holding the sceptre and the flower. But Anahita the Lady was also called the Gatherer, who summoned men to their ending.

Softly, the vizier murmured, ‘Why not do so? How can it matter, lord? May I send?’

The King of Kings lay still another moment, then he motioned assent, the gesture brief, indifferent. His rage seemed spent. His gaze, heavy-lidded, went to the fire and lingered there. Someone went out, at a sign from the vizier.

Time passed. In the desert beyond the fortress and the village below it a north wind rose. It swept across the sands, blowing and shifting them, erasing dunes, shaping others, and the lions, unhunted, took refuge in their caves among the rocks, waiting for night.

The blue moon, Anahita’s, rose in the late afternoon, balancing the low sun. Within the fortress of Kerakek, men went forth into that dry wind to kill three physicians, to kill a son of the king, to summon a son of the king, to bear messages to Kabadh, to summon a priest with Holy Fire to the King of Kings in his room.

And to find and bring one other man.

Rustem of Kerakek, son of Zorah, sat cross-legged on the woven Ispahani mat he used for teaching. He was reading, occasionally glancing up to observe his four students as they carefully copied from one of his precious texts. Merovius on cataracts was the current matter; each student had a different page to transcribe. They would exchange them day by day until all of them had a copy of the treatise. Rustem was of the view that the ancient Trakesian’s western approach was to be preferred in treatment of most—though not all— issues relating to the eye.

Through the window that overlooked the dusty roadway a breeze entered the room. It was mild as yet, not unpleasant, but Rustem could feel a storm in it. The sands would be blowing. In the village of Kerakek, below the fortress, the sand got into everything when the wind came from the desert. They were used to it, the taste in their food, the gritty feel in their clothing and bedsheets, in their own intimate places.

From behind the students, in the arched interior doorway that led to the family quarters, Rustem heard a slight rustling sound; he glimpsed a shadow on the floor. Shaski had arrived at his usual post beyond the beaded curtain, and would be waiting for the more interesting part of the afternoon lessons to begin. His son, at seven years of age, showed both patience and a fierce determination. A little less than a year ago he’d begun dragging a small mat of his own from his bedroom to a position just outside the teaching room. He would sit cross-legged upon it, spending as much of the afternoon as he was allowed listening through the curtain as his father gave instruction. If taken away by his mothers or the household servants he would find his way back to the corridor as soon as he could escape.

Rustem’s two wives were both of the view that it was inappropriate for a small child to listen to explicit details of bloody wounds and bodily fluxes, but the physician found the boy’s interest amusing and had negotiated with his wives to allow Shaski to linger outside the door if his own lessons and duties had been fulfilled. The students seemed to enjoy the boy’s unseen presence in the hallway as well, and once or twice they’d invited him to voice an answer to his father’s questions.

There was something endearing, even to a careful, reserved man, in a seven-year-old proclaiming, as was required, ‘With this affliction I will contend,’ and then detailing his proposed treatment of an inflamed, painful toe or a cough with blood and loose matter in it. The interesting thing, Rustem thought, idly stroking his neat, pointed beard, was that Shaski’s answers were very often to the point. He’d even had the boy answer a question once to embarrass a student caught unprepared after a night’s drinking, though later that evening he’d regretted doing so. Young men were entitled to visit taverns now and again. It taught them about the lives and pleasures of common men, kept them from aging too soon. A physician needed to be aware of the nature of people and their weaknesses and not be harsh in his judgement of ordinary folly. Judgement was for Perun and Anahita.

The feel of his own beard reminded him of a thought he’d had the night before: it was time to dye it again. He wondered if it was still necessary to be streaking the light brown with grey. When he’d returned from Ispahani and the Ajbar Islands four years ago, settling in his home town and opening a physician’s practice and a school, he’d considered it prudent to gain a measure of credibility by making himself look older. In the east, the Ispahani physician-priests would lean on walking sticks they didn’t need, gain weight deliberately, dole out words in measured cadences or with eyes focused on inward visions, all to present the desired image of dignity and success.

There had been some real presumption in a man of twenty-seven putting himself forward as a teacher of medicine at an age when many were just beginning their studies. Indeed, two of his pupils that first year had been older than he was. He wondered if they’d known it.

After a certain point, though, didn’t your practice and your teaching speak for themselves? In Kerakek, here on the edge of the southern deserts, Rustem was respected and even revered by the villagers, and he had been summoned often to the fortress to deal with injuries and ailments among the soldiers, to the anger and chagrin of a succession of military doctors. Students who wrote to him and then came this far for his teaching—some of them even Sarantine Jad-worshippers, crossing the border from Amoria—were unlikely to turn around and go away when they discovered that Rustem of Kerakek was no ancient sage but a young husband and father who happened to have a gift for medicine and to have read and travelled more widely than most.

Perhaps. Students, or potential students, could be unpredictable in various ways, and the income Rustem made from teaching was necessary for a man with two wives now and two children—especially with both women wanting another baby in the crowded house. Few of the villagers of Kerakek were able to pay proper physician’s fees, and there was another practitioner—for whom Rustem had an only marginally disguised contempt—in the town to divide what meagre income was to be gleaned here. On the whole, it might be best not to disturb what seemed to be succeeding. If streaks of grey in his beard reassured even one or two possible pupils or military officials up in the castle (where they did tend to pay), then using the dye was worth it, he supposed.

Rustem looked out the window again. The sky was darker now beyond his small herb garden. If a real storm came, the distraction and loss of light would undermine his lessons and make afternoon surgery difficult. He cleared his throat. The four students, used to the routine, put down their writing implements and looked up. Rustem nodded and the one nearest the outer door crossed to open it and admit the first patient from the covered portico where they had been waiting.

He tended to treat patients in the morning and teach after the midday rest, but those villagers least able to pay would often consent to be seen by Rustem and his students together in the afternoons as part of the teaching process. Many were flattered by the attention, some made uncomfortable, but it was known in Kerakek that this was a way of gaining access to the young physician who had studied in the mystical east and returned with secrets of the hidden world.

The woman who entered now, standing hesitantly by the wall where Rustem hung his herbs and shelved the small pots and linen bags of medicines, had a cataract growth in her right eye. Rustem knew it; he had seen her before and made the assessment. He prepared in advance, and whenever the ailments of the villagers allowed, offered his students practical experience and observations to go with the treatises they memorized and copied. It was of little use, he was fond of saying, to learn what al-Hizari said about amputation if you didn’t know how to use a saw.

He himself had spent six weeks with his eastern teacher on a failed Ispahani campaign against the insurgents on their north-eastern reaches. He had learned how to use a saw.

He had also seen enough of violent death and desperate, squalid pain that summer to decide to return home to his wife and the small child he had scarcely seen before leaving for the east. This house and garden at the edge of the village, and then another wife and a girl-child, had followed upon his return. The small boy he’d left behind was now seven years old and sitting on a mat outside the door of the medical chambers, listening to his father’s lectures.

And Rustem the physician still dreamt in the blackness of some nights of a battlefield in the east, remembering himself cutting through the limbs of screaming men beneath the smoky, uncertain light of torches in wind as the sun went down on a massacre. He remembered black fountains of blood, being drenched, saturated in the hot gout and spray of it, clothing, face, hair, arms, chest . . . becoming a creature of dripping horror himself, hands so slippery he could scarcely grip his implements to saw and cut and cauterize, the wounded coming and coming to them endlessly, without surcease, even when night fell.

There were worse things than a village practice in Bassania, he had decided the next morning, and he had not wavered since, though ambition would sometimes rise up within him and speak otherwise, seductive and dangerous as a Kabadh courtesan. Rustem had spent much of his adult life trying to appear older than he was. He wasn’t old, though. Not yet. Had wondered, more than once, in the twilight hours when such thoughts tended to arrive, what he would do if opportunity and risk came knocking.

Looking back, afterwards, he couldn’t remember if there was a knock that day. The whirlwind speed of what ensued had been very great, and he might have missed it. It seemed to him, however, that the outside door had simply banged open, without warning, nearly striking the patient waiting by the wall, as booted soldiers came striding in, filling the quiet room to bursting with the chaos of the world.

Rustem knew one of them, the leader: he had been stationed in Kerakek a long time. The man’s face was distorted now, eyes dilated, fevered-looking. His voice, when he spoke, rasped like a woodcutter’s saw. He said, ‘You are to come! Immediately! To the fortress!’

‘There has been an accident?’ Rustem asked from his mat, keeping his own voice modulated, ignoring the peremptory tone of the man, trying to reestablish calm with his own tranquillity. This was part of a physician’s training, and he wanted his students to see him doing it. Those coming to them were often agitated; a doctor could not be. He took note that the soldier had been facing east when he spoke his first words. A neutral omen. The man was of the warrior caste, of course, which would be either good or bad, depending on the caste of the afflicted person. The wind was north: not good, but no birds could be seen or heard through the window, which counterbalanced that, somewhat.

‘An accident! Yes!’ cried the soldier, no calm in him at all. ‘Come! It is the King of Kings! An arrow!’

Poise deserted Rustem like conscripted soldiers facing Sarantine cavalry. One of his students gasped in shock. The woman with the afflicted eye collapsed to the floor in an untidy, wailing heap. Rustem stood up quickly, trying to order his racing thoughts. Four men had entered. An unlucky number. The woman made five. Could she be counted, to adjust the omens?

Even as he swiftly calculated auspices, he strode to the large table by the door and snatched his small linen bag. He hurriedly placed several of his herbs and pots inside and took his leather case of surgical implements. Normally he would have sent a student or a servant ahead with the bag, to reassure those in the fortress and to avoid being seen rushing out-of-doors himself, but this was not a circumstance that allowed for ordinary conduct. It is the King of Kings!

Rustem became aware that his heart was pounding. He struggled to control his breathing. He felt giddy, light-headed. Afraid, in fact. For many reasons. It was important not to show this. Claiming his walking stick, he slowed deliberately and put a hat on his head. He turned to the soldier. Carefully facing north, he said, ‘I am ready. We can go.’

The four soldiers rushed through the doorway ahead of him. Pausing, Rustem made an effort to preserve some order in the room he was leaving. Bharai, his best student, was looking at him.

‘You may practise with the surgical tools on vegetables, and then on pieces of wood, using the probes,’ Rustem said. ‘Take turns evaluating each other. Send the patients home. Close the shutters if the wind rises. You have permission to build up the fire and use oil for sufficient light.’

‘Master,’ said Bharai, bowing.

Rustem followed the soldiers out the door.

He paused in the garden and, facing north again, feet together, he plucked three shoots of bamboo. He might need them for probes. The soldiers were waiting impatiently in the roadway, agitated and terrified. The air pulsed with anxiety. Rustem straightened, murmured his prayer to Perun and the Lady and turned to follow them. As he did, he observed Katyun and Jarita at the front door of the house. There was fear in their eyes: Jarita’s were enormous, even seen at a distance. She stared at him silently, leaning against Katyun for support, holding the baby. One of the soldiers must have told the women what was happening.