Полная версия:

Harmony: A New Way of Looking at Our World

Harmony

A NEW WAY OF

LOOKING AT OUR WORLD

HRH THE PRINCE OF WALES

TONY JUNIPER

IAN SKELLY

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Harmony 1

Nature 2

The Golden Thread 3

The Age of Disconnection 4

Renaissance 5

Foundations 6

Relationship 7

Index

Acknowledgments

Picture Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Harmony 1

Finds tongues in trees,

books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones,

and good in every thing.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

This is a call to revolution. The Earth is under threat. It cannot cope with all that we demand of it. It is losing its balance and we humans are causing this to happen.

‘Revolution’ is a strong word and I use it deliberately. The many environ-mental and social problems that now loom large on our horizon cannot be solved by carrying on with the very approach that has caused them. If we want to hand on to our children and grandchildren a much more durable way of operating in the world, then we have to embark on what I can only describe as a ‘Sustainability Revolution’ – and with some urgency. This will involve our taking all sorts of dramatic steps to change the way we consider the world and act in it, but I believe we have the capacity to take these steps. All we have to see is that the solutions are close at hand.

The Earth’s alarm bells are now ringing loudly and so we cannot go on endlessly prevaricating by finding one sceptical excuse after another for avoiding the need for the human race to act in a more environmentally benign way – which really means only one thing: putting Nature back at the heart of our considerations once more. But that is only the start of it. We must go much further. ‘Right action’ cannot happen without ‘right thinking’ and in that simple truth lies the deeper purpose of this book.

For more than thirty years I have been working to identify the best solutions to the array of deeply entrenched problems we now face. I have tried to do this, for instance, by demonstrating the principles of what I believe to be truly ‘sustainable’ agriculture through organic farming. I have tried to demonstrate the principles of ‘sustainable’ urbanism which can add social and environmental value to towns and cityscapes through mixed-use development, by placing the pedestrian at the centre of the design process, by emphasizing local identity and character and by the use of ecological building techniques. For many years I have been working to create effective partnerships between the private, public and non-governmental organization (NGO) sectors, not only to address the serious threats posed by climate change, but also to create major initiatives to try to save what is left of the world’s rainforests, as well as other major natural ecosystems – such as oceans and wetlands – which are now under dire threat of collapse. I have also tried for twenty-five years to encourage social and environmentally responsible business; to suggest a more balanced approach to certain aspects of medicine and healthcare; more rounded ways of educating our children and a more benign, ‘whole-istic’ approach to science and technology. The trouble is that in all these areas I have been challenging the accepted wisdom; the current orthodoxy and conventional way of thinking, much of it stemming from the 1960s but with its origins going back over 200 years.

The ‘slash and burn’ method of farming widely adopted in places like South Sumatra, Indonesia, clears virgin rainforest trees by burning them, producing 17% of Man-made CO2 emissions every year.

Perhaps I should not have been surprised that so many people failed to fathom what I was doing. So many appeared to think – or were told – that I was merely leaping from one subject to another – from architecture one minute to agriculture the next – as if I spent a morning saving the rainforests, then in the afternoon jumping to help young people start new businesses.

What I have actually been trying to demonstrate is that all of these subjects are completely inter-related and that we have to look at the whole picture to understand the problems we face. For not only does it concern the way we treat the world around us, it is also to do with how we view ourselves.

In all my efforts I have tried to make it clear that all these subjects suffer the same problems because they have become detached from important basic principles – the principles that produce the active state of balance which is just as vital to the health of the natural world as it is for human society. We call this active but balanced state ‘harmony’ and this book is dedicated to explaining how harmony works.

It is a book in which I hope to share the results of much thought, observation and reflection over the past thirty or forty years. I want to show what I have gained and achieved from studying the essential principles of harmony – how they work in Nature and how, if we ignore or flout them, the Earth’s precious life-support systems start to wobble and eventually may collapse. In some cases they have already fallen into a perilous state.

That is why our journey begins with a look at just what we are doing to our life-giving Earth after some two and a half centuries of intensive Industrialization. We all hope for solutions and that is why I want to end this journey by offering what might turn out to be a few of them, but the solutions must be understood in their proper context. I know from experience that if any solution is not deeply rooted in the right principles it will be of no use in the long term. In fact, quite the contrary, it will tend to compound the problems we already have. That is why I also want to put our present situation in its true historical context. We have to realize that we are travelling on the wrong road, but we need to understand why.

It is very strange that we carry on behaving as we do. If we were on a walk in a forest and found ourselves on the wrong path, then the last thing we would do is carry on walking in the wrong direction. We would instead retrace our steps, go back to where we took the wrong turn, and follow the right path. This is why I feel it is so important to offer not just an overview of our present situation and not just a list of the solutions. I certainly want the world to wake up to the fact that we are travelling in a very dangerous direction, but it is crucial that we retrace how this has come to be, otherwise we will not head onto a better path in the future.

Crisis of perception

I would suggest that one of the major problems that increasingly confronts us is that the predominant mode of thinking keeps us firmly on this wrong path. When people talk of things like an ‘environmental crisis’ or a ‘financial crisis’ what they are actually describing are the consequences of a much deeper problem which comes down to what I would call a ‘crisis of perception’. It is the way we see the world that is ultimately at fault. If we simply concentrate on fixing the outward problems without paying attention to this central, inner problem, then the deeper problem remains, and we will carry on casting around in the wilderness for the right path without a proper sense of where we took the wrong turning.

That is why I wanted to put this book together. With Tony Juniper and Ian Skelly’s help, I want to demonstrate that we have grown used to looking at the world in a particular way that obscures the danger of a very disconnected approach. All of the solutions I want to suggest depend for their success upon looking at the world in a different way. It is not strictly a new way and that is why we will travel back in time to see the world as the ancients saw it, but it is a way of seeing things that stands very much at odds with what has become the only reasonable way of looking at the world. If that reaction starts to grow then I urge you to hold onto one important fact, that this timeless view of things is rooted in the human condition and in human experience.

It may be a bit daunting if I suggest at the outset that I want to include in this journey a brief tour of ‘traditional philosophy’ but I can assure you that such an explanation will be painless and that everything will be explained simply. Not least because it is simple.

Perhaps it is worth remembering what that word ‘philosophy’ means. It is a combination of two Greek words: one meaning ‘love of’ and the other meaning ‘wisdom’. So, to be a ‘philosopher’ is to be a lover of wisdom, and the wisdom this refers to is human wisdom, of the sort that has been handed down from generation to generation in all societies throughout the world. Until quite recently, this time-honoured wisdom framed the way all civilizations behaved. It emphasized the right way to see our relationship with the natural world, it taught in practical ways how to work with the grain of Nature rather than against it, and it warned of the dangers of overstepping the limits imposed by Nature on herself. In short, this wisdom emphasized the need for, and the means of maintaining, harmony.

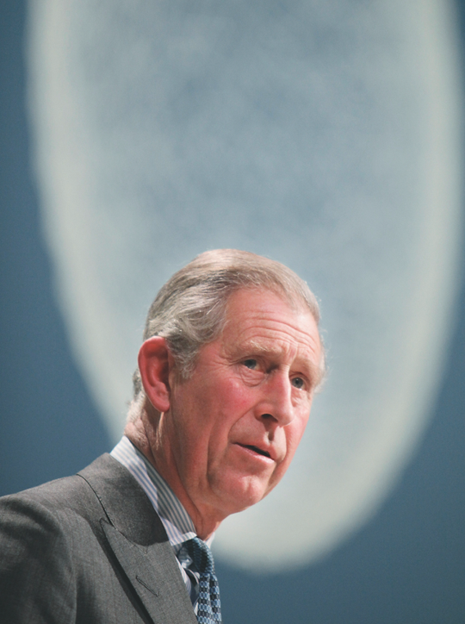

Islamic patterning depicted in the Attarine Madrasa Fes. This geometry is found throughout the natural world and is demonstrated in the relationships between planetary orbits and their proportions. As we shall see, it is the grammar that underpins the whole of life.

Ancient wisdom

As I first struggled to understand what age-old thinking like this could teach us, I began to notice a curious connection between the many problems our modern world view had created and a subject that increasingly fascinated me.

The five-petalled rose pattern traced over 8 years in the skies above Earth by our nearest neighbour, Venus, depicted 400 years ago by the German astronomer, Johannes Kepler. It is the source of the familiar fivepointed star found in many natural forms and in the world’s sacred architecture.

It was a surprising subject. It was the design and symbolism of the architecture of the temples, mosques, and cathedrals of the world. The more I learned about it, the more I became aware that there was a similarity between the way ancient civilizations built their sacred structures and the way the natural world itself is structured and behaves. The ratios and proportions that define the way natural organisms grow and unfold are the same as those that underpin the structure of the most famous ancient buildings. I was among a number of people who began to piece together a great jigsaw which revealed, much to my surprise, a profound insight into what really lay at the heart of ancient thinking. I shall explain this with lots of images in the section called ‘The Grammar of Harmony’ in Chapter 3, which gives context to the history of modernity, simply because there is a direct relationship between the patterns that inspired the builders of all those great masterpieces of sacred architecture and the way the natural world operates when it is in a healthy state of balance. The two speak with the same ‘grammar’.

Seeing this, I began to realize that the great juggernaut of industrialization relies upon a somewhat aberrant kind of language – a man-made one – which articulates a world view that ignores Nature’s grammar. Much of the syntax of this synthetic language is out of synchrony with Nature’s patterns and proportions and this is why it so often jars with the language of Nature. This is why so many Modernist buildings don’t feel ‘right’ to so many people, even though they may find them clever; or perhaps why we feel uncomfortable with factory farming, even though it makes economic sense because it supplies such a lot of food at such low prices; or why we feel something is missing from a form of medicine that treats the body like a machine and does not accommodate the needs of the mind or the spirit.

I find, by contrast, that if people are encouraged to immerse themselves in Nature’s grammar and geometry – discovering how it works, how it controls life on Earth, and how humanity has expressed it in so many great works of art and architecture – they are often led to acquire some remarkably deep philosophical insights into the meaning and purpose of Nature and into what it means to be aware and alive in this extraordinary Universe. This is particularly so in young people and the results of such immersion are as heartening as they are surprising. They help to point to the changes in thinking that we need to make to achieve the wider vision of a Sustainability Revolution.

Essentially it is the spiritual dimension to our existence that has been dangerously neglected during the modern era – the dimension which is related to our intuitive feelings about things. The increasing tendency in mainstream Western thinking to ignore this spiritual dimension comes from a combination of the growth in cynicism during the latter half of the twentieth century and the wholesale dismissal of the big philosophical questions about our existence. The dominant world view only accepts as fact what it sees in material terms and this opens us up to a very dangerous state of affairs, not least because the more extreme this approach becomes, the more extreme the reaction tends to be at the other end of the scale, so we end up with two fundamentalist, reductionist camps that oppose each other. On the one side, a fundamentalist secularism and on the other, fundamentalist religions. This seems to happen in Christianity as it does in Islam and, wherever it happens, the more puritanical and literal the religious interpretation becomes, the more a culture abandons and then even attacks the age-old, symbolic interpretations of its own tradition – those teachings which actually emphasize the necessary limits to our behaviour. With so much emphasis on the historical accuracy of the origins of a religion, the search for mystery appears to give way to a vain search for certainty. What was a traditional attitude becomes a ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’ one, all too intolerant of restraint, and so the limits – Nature’s necessary limits – end up being overshadowed by dogma.

Has this come about as a result of one dimension of our outlook becoming too dominant in our thinking? And if so, what is the nature of that outlook? Having considered these questions long and hard, my view is that our outlook in the Westernized world has become far too firmly framed by a mechanistic approach to science, the one that has increasingly prevailed in the West for the past four hundred years. This approach is entirely based upon the gathering of the results that come from subjecting physical phenomena to scientific experiment. It is called ‘empiricism’ and it is, if you like, a kind of language. It is a very fine one, but it is a language not able to fathom experiences like faith and the meaning of things. Nor can it articulate matters of the soul. It is now the only popularly trusted level of language we may use to articulate our understanding of the world. Don’t get me wrong, it has a very valuable role to play, but the trouble is, empiricism now assumes authority beyond the area it is capable of considering and, consequently, it excludes the voices of those other levels of language that once played their rightful part in giving humanity a comprehensive view of reality – that is, the philosophical and the spiritual levels of language. This is why it conveniently elbows the soul out of the picture.

Think of something as basic as the conversation that might take place in a biology lesson where a science teacher is called upon by pupils to address the moral and ethical questions of whether or not it is a good thing to manipulate genes. At that point, does the teacher act as a philosopher or remain a science teacher? I am pretty sure that the majority of teachers would certainly feel very uncomfortable about assuming the role of spiritual guide when such questions arise. The essential point here is, how far our empirical knowledge can go before it begins to encroach on territory it is not qualified to discuss. Let me be clear about it. Science can tell us how things work, but it is not equipped to tell us what they mean. That is the domain of philosophy and religion and spirituality.

Let me say again – empiricism has its part to play, but it cannot play all of the parts. And yet, because it tries to, we end up with the general outlook that now prevails. The language of empiricism is now so much in the ascendant that it has authority over any other way of looking at the world. It decides whether those other ways of looking at things stand up to its tests and therefore whether they are right or wrong.

This has not always been the case. A specifically mechanistic science has only recently assumed a position of such authority in the world and I want to show how this came to be: how its influence from the seventeenth century onwards spread, and slowly but surely excluded those other levels of language that were once much more a part of the conversation. For not only has it prevented us from considering the world philosophically any more, our predominantly mechanistic way of looking at the world has also excluded our spiritual relationship with Nature. Any such concerns get short shrift in the mainstream debate about what we do to the Earth. They are dismissed as outdated and irrelevant because a thing does not exist if it cannot be weighed or measured. And so we live in an age which claims not to believe in the soul. Empiricism has proved to us how the world really fits together and how it really works and, on its terms, this has nothing to do with God. There is no empirical evidence for the existence of God, so therefore God does not exist. That seems a very reasonable, rational argument, so long as you go along with the empirical definition of God as a ‘thing’. I presume the same argument can also be applied to the existence of thought. After all, no brain-scanner has ever managed to photograph a thought, nor a piece of love for that matter, and it never will, so, by the same terms, thought and love do not exist either.

Behind the familiar images of sacred sites like this figure of Christ on Canterbury Cathedral in England, is a symbolism that goes beyond the particular culture and time in which it was created.

That may appear flippant, but my point is that this is the consequence of doggedly following Galileo’s line that there is nothing in Nature but quantity and motion. Over time it has added up to a serious situation where we are no longer able to view the world much beyond its surface and its appearance. We are persuaded, instead, to follow a way of being that denies the non-material side to our humanity even though, contrary to what is supposed to be a growing popular belief, this other half of ourselves is actually just as important as our rational side, if not more so. It is our means of relating to the rest of the natural world and this is why I have long felt so alarmed that our collective thinking and predominant way of doing things are so dangerously out of balance with Nature. We have come to function with a one-sided, materialistic approach that is defined not by its inclusiveness, but by its dismissal of those things that cannot be measured in material terms.

At work at Highgrove, my home in Gloucestershire, England, laying hedges using age-old traditional techniques. Hedgerows are not only long-lasting, sturdy ways of keeping stock in fields, they are havens for wildlife and are a time-honoured way of stopping the erosion of top soil.

This is peculiar to the history of the West. In general, people from else-where in the world do not understand how Nature has become so secularized. Even many people in the West fail to recognize that so much modern science is not simply an ‘objective’ knowledge of Nature, but is based upon a particular way of thinking about existence and geared to the ambition to gain dominion over Nature. The way in which this has happened has a lot to do with the numbing of our vital inborn or ‘inner tutor’, the so-called human ‘intuition’.

Our intuition is deeply rooted in the natural order. It is ‘the sacred gift’, as Einstein called it. Many sacred traditions refer to it as the voice of the soul: the link between the body and mind and therefore the link between the particular and the universal. If we were to recognize this, we would perhaps once again begin to see our existence in its proper place within creation and not in some specially protected and privileged category of our own making. That is hardly likely to happen as long as scientific rationalism continues to turn people away from any form of spiritual practice or reflection by perpetuating what seems to me to be a widespread confusion. It often comes to light during one of those typical interrogations of a person who experiences faith. They are expected to give empirical proof that God exists. As I hope will become clear later, this question can only be taken seriously when faith and the Divine are regarded as material objects.

A much more integrated view of the world and our relationship with it existed throughout ancient history and right up to that critical period in seventeenth-century Europe when Western thinking began to take a more fragmented view of things. It is not so much the fragmentation, but its causes that I have come to see are the linchpins of the problem and that is why I feel it necessary to explore, in the lightest way possible, how the modern world was born and how we came to regard the world in the overtly ‘mechanistic’ way we do today. By persisting in this view, we ignore, abandon and waste the wisdom, knowledge and skills that have been built up over the entire course of human history. It is, perhaps, not so understood as it should be that so much of the wisdom I am referring to came to humanity from revelation. Revelation is not deemed possible from an empirical point of view. It comes about when a person practises great humility and achieves a mastery over the ego so that ‘the knower and the known’ effectively become one. And from this union flows an understanding of ‘the mind of God’. I cannot stress it firmly enough: by dismissing such a process and discarding what it offers to humankind, we throw away a lifebelt for the future.