Полная версия:

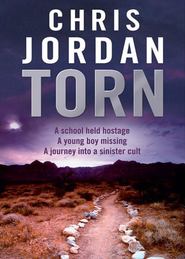

Torn

CHRIS JORDAN

TORN

For the brave ones,

Molly & Annie Philbrick

PROLOGUE

The Pinnacle Conklin, Colorado

He awakens with no memory of who he is, or how old he is, or why he should be in this palatial chamber. No, not so much a chamber as a grand hall, with one distant wall formed entirely of high, soaring glass, beyond which magnificent mountains rise from a stark landscape.

Men have gathered at his bedside. Doctors? Attendants? No, they are more like acolytes, for their eyes defer to him in supplication. Is he a prince? A king? A movie star?

He feels like a movie star. The enormous, glass-walled space, with its high curved ceiling melded into shadows, it has the look of a set, something designed for film. But if he’s a movie star—the star of this scene, surely—why can’t he recall his lines? Where have all the words gone?

“Good morning, sir,” says one of the acolytes, looming over the bed. A homely gnome of a man who looks vaguely familiar. “How are you feeling today?”

He searches for the words, wanting to respond, but the only thing readily available is one simple syllable.

“Ha,” he says, suddenly aware of the dryness in his mouth, a thickness in his throat that makes it hard to swallow.

“Bring water!”

A straw appears. He refuses, taking direction from his body, an instinctive recoiling from anything that must pass his lips. And then his mind catches up, slowly unfolding in all its complexity, and with a shudder he remembers that someone is trying to poison him. It is poison that thickens his throat and slows his mind. Poison that traps him in this bed.

He struggles but the poison has made him weak. A needle slips into a vein and the poison drips into him. A subtle, insidious, undetectable toxin that seeps into the cells of his brain, interfering with synaptic response. The bag appears to be harmless saline solution, but it cannot be. The notion that he’s being slowly poisoned is something that he has deduced, rather than proved. The theory is highly probable because it’s the only explanation for his condition: under no other circumstance would men like this—mere drones attending the queen—dare to treat him in this fashion. Unless they had betrayed him.

The drone with the homely face dares to speak for him, as if interpreting the words that clot in his throat.

“Stand clear. He wishes to see the mountains.”

He has issued no such command—what does he care of mountains?—and then the rising sun strikes the peaks in just such a way, as if etching them into the sky, that his labored breathing catches. He knows it is only reflected light glancing off stone, ever so briefly imprinted on his retinas, but the image has the power to bring tears to his eyes.

He remembers, then. For a fleeting moment he regains a sense of who he is. Not a king, exactly, and certainly nothing as insignificant as a mere movie star. He is like the mountain and these lesser beings seek to erode him. They scratch and fuss and block him from the light. They drip their pathetic poisons like rain upon the mountain and like the mountain he will prevail, he will survive, in the most fundamental way, long after they are gone and forgotten.

The drone looks away, as if aware of the greater man’s thoughts and ashamed for his own. He glances at an expensive wristwatch, feigning patience, and when the sunrise ceases to color the mountains he calls for a screen to be drawn around the bed.

Nurses attend to him, changing his catheter, evacuating his bowels. Sponging him down, patting him dry, as if he was some mewling infant and not…whatever he is. He struggles to hold a sense of self. Who is he? Who? A great man in a glass room, beset by lesser species, suffering various indignities. Indignities soon forgotten, absorbed by the scent of baby powder. Beyond that he does not recall.

Nothing holds, nothing stays.

Drip, drip, drip.

“Sir? Your wife is here. Would you like to see her?”

With great effort, fighting up through the silky gauze that swathes his mind, he musters a single “Ha.”

A woman who claims to be his wife floats into view, and if he could laugh, he would. Because it is beyond a bad joke. The woman is old enough to be his mother. Regal, beautifully preserved, expensively coiffed, and obviously very wealthy. But old.

As if he would marry a woman like that! He finds the notion so absurd that it’s hard to hold her words in his mind and sort them into something meaningful.

“Arthur? Can you hear me, darling? Blink if you can understand. I’ve done exactly what you requested. What you spelled out months ago. I followed your instructions precisely, do you understand?” She studies him, then announces triumphantly to the others, “He blinks! He understands!”

He understands only that she must be an elaborate fraud. An aging actress contracted to play a role. She may be in league with the fawning acolyte. Whatever she is, whatever her motives, he cannot trust anything she says.

“You have the best doctors, my darling. The very best in the world. We are not giving up on you, do you understand?” She leans in close, wafting the scent of lilies, and whispers words meant only for him. “You can’t die, Arthur. Not now, not ever. Whatever happens, you must come back to us. One way or another, you must live forever.”

Then she draws away, dabbing at her eyes, and vanishes from his sight line. The scent of lilies. For a moment he knows with absolute conviction who he is and how he has come to be in this place.

He is the one, the Ruler of Rulers, he is all minds in one.

A moment later he begins to drool.

Part I

Humble, New York

1. A Simple, Ordinary Lif

The day before my son’s school exploded, he asked me if heaven has a zip code. We’re having breakfast, me the usual fruit yogurt, Noah his mandatory Cocoa Puffs, cup of ‘puffs’ to one-half cup milk, precisely. He licks his spoon, gives me that wide-eyed mommy-will-know look, and asks the big question.

“Not a real zip code,” he adds, “a pretend zip code, like for Santa. Like for writing a letter to Dad. Just to say hello, let him know we’re okay and everything.”

It’s a strange and wonderful thing, the mind of a ten-year-old child. Last night, as we read our book before bed—the very exciting Stormrider—Noah had asked, out of nowhere, “How we doing, Mom?”

We’d both known exactly what he meant by that—the slow, painful rebuilding of our world—and without missing a beat I’d responded, “We’re doing okay,” and he’d filed it away in his amazing brain and twelve hours later, out pops the idea of writing a letter to his dead father.

“You write it,” I suggest, “I’ll find out about the zip code.”

“Deal,” he says, and grins to himself, mission accomplished.

Then he calmly and methodically finishes his cereal.

My husband, Jed, used to say that Humble, New York, was well named, but only because ‘Hicksville’ was already taken. Humble being a small, one-of-everything town thirty miles outside of Rochester. One convenience store, one barber/beauty shop, one police station, one firehouse, one elementary school. At last count there were more farm animals—mostly dairy cows, cattle, and sheep—than people.

We moved here shortly before Noah was born and my first impression wasn’t exactly positive. I’m a New Jersey girl, a mall rat at heart, and the idea of living upstate in sight of a cornfield wasn’t exactly my dream come true. Postcards are meant to be mailed, not lived in. But Jed was convinced a small town would be safer than Rochester, where he’d just been hired, and which has the usual problems with poverty, drugs, and empty factories, so when he found the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ on the Internet there was no way I could say no.

Not that I ever said no to Jed. What he wanted, I wanted. We agreed that we had to get out of the city, had to make a new life for ourselves, as far away from his crazy family as possible. It was all good, and for a while—nine wonderful years—we lived the American dream, or as near as real people can live it. Not that everything was perfect. Sometimes Jed brought home his job tensions—he was an electrical engineer with a struggling company, lots of pressure there. Sometimes I let my resentment—how did his family situation get to run my life?—overpower my own good sense.

Sure, we squabbled now and then, all couples do, but we never went to bed angry. That was our rule. Arguments had to be settled before we hit the sheets. I’d grown up in a family that fought—my parents divorced when I was in high school—and Jed’s parents had been, to say the least, dysfunctional as human beings, and therefore more than anything we’d both longed for normality. A normal family in a small town, living a simple, ordinary life. The fact that Jed’s family was far from normal no longer mattered, because we were making our own family, our own life, far from them.

Along the way this suburban Jersey girl got pretty good at stripping old plaster, hanging new Sheetrock, painting and wallpapering, the whole nine yards—whatever that means. My old posse would just die if they knew prissy little Haley Corbin had learned how to solder leaky pipes, unclog blocked drains, refinish old kitchen cabinets. With Jed working so hard, and being dispatched as a troubleshooter to distant locations, much of the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ renovation was left to me. I had no choice but to take off my fabulous custom-lacquered fingernail extensions and get to work. This Old House and HGTV became my gurus. I attended every workshop offered at the nearest Home Depot.

I took notes. I paid attention. I learned a thing or two.

My personal triumph, after studying a chapter on home wiring repairs and puzzling over a diagram, was wiring up a three-way switch for a new light in the foyer. Jed was truly amazed by that little adventure. I mean his jaw dropped. Claimed my body had been taken over by alien electricians. I offered to flip his switch, and did, right there on the stairs with Noah fast asleep in his crib.

Life was good. No, life was great. We’d done it. We’d managed to escape from a really bad scene and get a new start. Then it ended, as sudden as a midnight phone call, and the kind of hole it left cannot be plastered over, not ever. The best you can do is push your way through the days, concentrate on being the best mom possible, even if you know in your bones it can never really make up for what’s missing.

Lately Noah seems to be faring better, which is good. He’s not acting out in class quite so much. He’s testing me less, a great relief. That’s the thing about kids. When the impossible bad thing happens, they accept it. Eventually they adapt, and, as the saying goes, ‘get on with their lives.’ One of those clichés that happens to be true. But really, what choice do we have?

“Mom?” says Noah, holding up his wristwatch. A gift from his dad he has never, to my knowledge, taken off.

“Ready?”

“Like five minutes ago. You were noodling, Mom.”

Noah doesn’t approve of me ‘noodling’because he thinks it makes me sad. He may have a point. I feel better when I’m busy, focused in the moment. Not wallowing in daydreams.

Moments later we’re out the door, into the car.

Noah never takes the bus to school, not because he wouldn’t like to—he has made his preference known—but because of the seat belt thing. No seat belts in buses, which drives me nuts. We’re legally required to strap them into car seats until they shave, make sure they wear helmets while riding bikes and boards, but school buses get a pass? What’s that all about?

Jed always thought I overreacted on the subject and maybe he was right, but I can’t help picturing those big yellow buses upside down in a ditch, or in a collision, small bodies hurtling through the air like human cannonballs. So I drive my boy to Humble Elementary School—distance, three point four miles—and see him inside the door with my own eyes. And when school gets out I’ll be right here waiting to pick him up and see that he gets home safely.

A mother can’t be too careful.

2. Waiting For The Voice

Roland Penny watches from behind the filthy windows of his 1988 Chevy van as the children enter the school. The little brats with their backpacks and their enormous shoes. Probably need the big shoes so they don’t tip over from the weight of the backpacks—they look like miniature astronauts stomping around in low gravity.

Strange, because when Roland himself attended this very same school, he, too, had big fat shoes with Velcro fastenings and a Mickey Mouse backpack, which he thought was cool at the time. Now he knows how small and ridiculous he must have looked to the adult world. How pitiful and partially formed—barely human, really. A lifetime ago, long before his mind was successfully reprogrammed with an understanding of the forces that rule the universe. Before he understood the fundamentals. Before he evolved to his present phase.

The cell on his belt vibrates. Very subtle, almost a tickle, but there it is. Incoming, baby. He touches the phone, hears the bright voice in his headset. A rich, persuasive voice that always seems to be perfectly in tune with his harmonic vibrations.

He listens intently. After a moment he responds.

“Yes, sir. I’m in place, on station.”

The Voice, his own personal guidance mechanism, helps him keep focus. Centers him in the vortex. Reveals the secret rules and structures. Shows him the way. The Voice calms him, guides him, persuades him.

The Voice thinks for him, which is a great relief.

“Yes, sir, understood. Wait for the chief. Will do.”

The connection is severed, causing him to wince. It’s a physical sensation, losing connection to The Voice. Like having the blood supply to his brain cut off. But he has trained for this day for the past four months, guided every step of the way, and he knows The Voice will come to him exactly when he needs it, and not a moment before.

Roland Penny sits back in the cracked, leatherette seat of his crappy van and smiles at the thought of the new vehicle he’s going to purchase when this mission is successfully concluded: a brand-new Escalade with all the options! Sweet. For now The Voice tells him that his old van is good cover. Patience. Complete the mission, then savor the reward. The Humble police chief is due at the top of the hour. Doubtless he will be on time, but if not, remain calm. Roland understands that he must not panic, must not deviate from the plan. If he deviates in any way, The Voice will know, and that would be bad.

Very bad.

3. Prime Numbers

Noah loves his homeroom teacher, Mrs. Delancey. Mrs. Delancey is kind and smart and funny. Also, she’s beautiful. Not as beautiful as his mother, of course—Mom is the most beautiful person on the entire planet—but Mrs. Delancey is pretty in a number of interesting ways. Her hair, which she keeps putting back in some sort of elastic retainer thing, the way her dark eyes roll up in amusement when something funny happens, and her nice, fresh vanilla kind of smell, which Noah finds both familiar and reassuring.

The most attractive thing about her, though, is the smart part. At ten years of age Noah Corbin is an uncanny judge of intelligence. He can tell right away if an adult is as smart as he is, and Mrs. Delancey passes. In fourth grade there’s no more baby stuff, no picture books or adding and subtracting puppy dogs and rabbits. They’re learning real science and real math, complicated stuff that teases pleasantly at his brain. Mrs. Delancey isn’t just reading from the textbooks or going through the motions—not like dumb-dumb Ms. Bronson who just about ruined third grade—Mrs. Delancey really understands the concept of factors and multiples and even prime numbers.

In Noah’s mind, prime numbers glow with a special kind of magic. Almost as though they’re alive. Alive not in the human way of being alive, of course, but in the way that certain numbers can have power. When he thinks of, say, 97, it seems to have a pulse. It’s bursting with self-importance—look at me!—as if it knows it can’t be divided. Because dividing by one doesn’t really count. That’s just a trick that makes calculations work, but everybody who understands knows that what makes prime numbers prime is that they can’t be cleanly or perfectly divided. They remain whole, invulnerable, no matter what you try and do to them. Primes are like Superman without the Kryptonite. Which is actually how Mrs. Delancey described them on the very first day of math, totally blowing him away. What an amazing concept!

Yesterday Mrs. Delancey gave him a special tutoring session during recess. Noah had not wanted to go out on the playground at that particular moment—it just didn’t feel right, he couldn’t explain why—and lovely Mrs. Delancey had opened up a high-school-level math book and explained about dihedral primes. Dihedrals are primes that remain prime when read upside down on a calculator. How cool is that! Mrs. Delancey knew all about dihedrals and even more amazing, she knew he’d understand, even though it was really advanced.

Noah, having stowed his backpack, sits at his desk, waiting for the class to be called to order. At the moment mayhem prevails. Children run wild. Not exactly wild, he decides, there is actually a sort of pattern emerging. His classmates are racing counterclockwise around and around the room, a sweaty centrifuge of fourth-grade energy, driven mostly by the Culpepper twins, Robby and Ronny, who have been selling their Ritalin to Derek Deely, a really scary fifth grader who supposedly bit off the finger of a gym instructor in Rochester, where he used to go to school. Necessitating that his entire family escape to Humble, where they’re more or less in hiding. That’s what everybody says.

Noah finds it perfectly believable that a kid would bite off a teacher’s finger. He’s been tempted himself, more than once. Although that was mostly last year, when everybody thought that feeling sorry for him was the way to go. Like Ms. Kinnison always trying to hug him and ‘check on his feelings.’ Which really should be against the law, in Noah’s opinion. Feelings were personal and you weren’t obliged to share them with dim-witted adults who didn’t know the first thing about aerodynamics, momentum effects, or dead fathers.

“Take your seats! Two seconds!”

Mrs. Delancey hasn’t been in the room for a heartbeat and everything changes. Two seconds later every single child has plopped into the correct seat, as if by magic. As if Mrs. Delancey has waved a wand and made it so. While the truly magical thing is that she has no wand—Noah doesn’t believe in magic, not even slightly, not even in books—but has the ability to command their attention.

“Deep breaths everyone,” she instructs, inhaling by way of demonstration. “There. Are we good? Are we calm? Excellent!”

As Mrs. Delancey takes attendance, checking off their names against her master list, Noah decides that she is the living equivalent of a human prime number. Indivisible, invulnerable. Superteacher without the Kryptonite.

4. The Cheese Monster

The amazing thing, given his family background, is how normal Jed turned out. Okay, my late, great husband was brilliant—after he died, his coworkers kept saying he was some kind of genius, the smartest guy in the company—so maybe having a brilliant mind isn’t exactly normal, but in all the usual normal human ways Jed was normal. He loved me unconditionally and I loved him back the same way. We wanted to make a life together, raise children, do all the normal kinds of things that normal people do. And we did, so long as we both shall live.

Not that it wasn’t a challenge. And luck played a role, right from the start. It was luck that we ever met. Blame it on Chili’s. Jed was working his way through Rutgers—he’d already cut all ties with his family—slogging through four-hour shifts at a local Chili’s three days a week and full-time—often twelve hours per shift—on weekends. Forty hours busing tables, thirty hours in lecture halls and labs, another thirty hitting the books—it didn’t leave much time left over for things like sleeping, let alone meeting mall girls from South Orange who just happen to be at a Chili’s celebrating a friend’s birthday, downing way too many Grand Patrón margaritas. Mall girls who get whoopsy drunk and barf in a tub of dirty dishes. Mall girls who are then so humiliated they burst into tears and cry inconsolably.

Well, not inconsolably. I wasn’t so drunk I didn’t have the presence of mind to take the dampened napkins the hunky busboy provided to clean up with, or let him walk me outside so I could get some fresh air. He was so sweet and kind, and so careful not to put his hands on me, even though I could tell he wanted to. And when I came back the next evening, cold sober, to formally apologize, we sat down and had a coffee and by the time we stood up I knew he was the man for me. The very one in the whole wide world. All the other boys—hey, I was a hot little mall girl—all the others were instantly erased, gone as if they’d never existed. My heart beat Jedediah, and it still does.

Jedediah, Jedediah, can’t you hear it?

* * *

After dropping Noah off at school I stop by the Humble Mart Convenience Store for a loaf of bread and some deli items—the selection is limited but of good quality—but mostly to hear the latest gossip being shared by Donald Brewster, the owner/manager. Called ‘Donnie Boy’ by everyone in town, which dates from his days as a high school football hero. Donnie Boy Brewster keeps a glossy team photo up behind the deli counter, blown up to poster size. When the customers mention it, and they do so frequently, Donnie Boy rolls his eyes and chuckles good-humoredly and says who is that kid? What happened to him, eh?

The ‘eh’ being the funny little Canadian echo some of the locals have, from living so close to the border.

Anyhow, Donnie Boy is one of the nice ones, a local kid who made good by staying local. He obviously loves his store, keeps it spiffy clean and well stocked, and he knows everything that’s going on in the little village of Humble and, best part, loves to share. Even with recent immigrants like me.

“Hey, Mrs. Corbin!”

I’ve given up trying to get him to call me Haley. All of his customers are Mister, Missus, or Miz, no exceptions. On the street he’ll call me Haley, but when he’s on the service side of the counter, I remain Mrs. Corbin. Donnie Boy’s rules.

Donnie in his little white butcher’s cap and his long bulbous nose and radar scoop ears, going, “We’ve got that Swiss you like. No pressure.”

“No, no, give me a quarter. It’s Noah’s favorite.”

“Coming right up,” he says, placing the cylinder of cheese in the slicing machine. “Thin, right?”

“Thin but not too thin.”

“Not so thin you can read through it. Got it. D’ja hear about the dump snoozer?”

Why I come here, to hear about mysterious local events like dump snoozing.

“Old Pete Conrad. You know, out Basel Road? The farmhouse with the leaning tower of silo?”

Happily, I am indeed familiar with the ‘leaning tower of silo.’ Nice old farmstead, with the main house kept up and painted and all the other buildings, barns and sheds in a state of disrepair, including a faded blue silo that’s seriously out of plumb. I don’t know Mr. Conrad personally, but have seen him at a distance, fussing at an ancient tractor.