Полная версия:

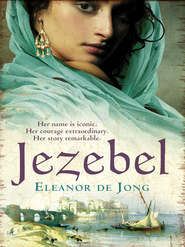

Jezebel

Eleanor de Jong

Jezebel

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

AVON

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

A Paperback Original 2012

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 2012

JEZEBEL. Copyright © Working Partners Two 2012. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Eleanor de Jong asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9781847562555

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2011 ISBN: 9780007443215

Version: 2018-07-19

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

872 BC – Girl

Chapter One

Salt spray glistened in the stallion’s mane and stung Jezebel’s…

Chapter Two

There was indeed a faintly frosty welcome when she returned…

Chapter Three

Later that evening, Jezebel entered her father’s crowded chambers for…

Chapter Four

In the sharp morning light, Tyre looked almost more beautiful…

Chapter Five

She was late to the banquet that night, having spent…

Chapter Six

Jehu held his hand out to Jezebel as she stepped…

Chapter Seven

‘Hail, Hail!’ cried the crowd at the head of the…

Chapter Eight

The next morning it was not the unfamiliar light that…

Chapter Nine

‘This city was built to keep strangers out,’ murmured Jezebel…

Chapter Ten

The chambers she had been allocated were a pleasant surprise.

Chapter Eleven

In the light from flickering lanterns, the young woman stared…

Chapter Twelve

Jezebel tried to sit still on the couch in her…

Chapter Thirteen

In the light of dawn the Palace did seem more…

Chapter Fourteen

A few days later, Jezebel stood in front of a…

Chapter Fifteen

The hot and barren summer did little more than stifle…

Chapter Sixteen

Jezebel recovered quickly from the birth and within two days…

Chapter Seventeen

From the roof of the Palace, Jezebel could see the…

Four years later 868 BC – Mother

Chapter Eighteen

‘Yahweh has blessed the House of Omri once again!’ cried…

Chapter Nineteen

The energy of her fury abated during a sleepless night…

Chapter Twenty

The courtyard was already crowded with crates and chests as…

Chapter Twenty-One

She didn’t dwell on Jehu’s unceremonious departure for long. As…

Chapter Twenty-Two

The trees in the Palace courtyard were just beginning to…

Chapter Twenty-Three

That evening in the King’s office, Ahab sat at his…

Chapter Twenty-Four

She couldn’t reach the city before the processions of priests…

Chapter Twenty-Five

Ahab had been sitting on his bed, head in his…

Eight years later 860 BC – Queen Consort

Chapter Twenty-Six

Jezebel shifted her weight on Ahab’s throne. At least none…

Chapter Twenty-Seven

But that afternoon, Balazar insisted on a private audience with…

Chapter Twenty-Eight

‘Come away from the window,’ said Beset. ‘You will catch…

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Boaz thrust open the Council Chamber doors.

Chapter Thirty

Jezebel carefully removed the Consort gown before going up to…

Chapter Thirty-One

Jezebel made a great fuss of Athaliah that afternoon. They…

Chapter Thirty-Two

The Palace felt empty after Balazar and Esther returned to…

Chapter Thirty-Three

Though night had long since fallen, the Council Chamber was…

Chapter Thirty-Four

In the days that followed Naboth’s death, the mood in…

Chapter Thirty-Five

Athaliah grabbed her mother tightly, sobbing into Jezebel’s neck, her…

Chapter Thirty-Six

As the carriage turned onto the causeway at Tyre, Jezebel…

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Two days later, Jezebel stood alone on the roof of…

Chapter Thirty-Eight

For more than a week, Jezebel remained inside the Palace…

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Jezebel left the throne room, her chin held high, but…

Five years later 854 BC – Regent

Chapter Forty

From the banks of the River Jordan, the encampment of…

Chapter Forty-One

Through the archway of the Court of the Priests, Jezebel…

Chapter Forty-Two

Though it pained Jezebel dreadfully to leave Athaliah behind in…

Chapter Forty-Three

The plains around Samaria were almost unrecognisable, so thick were…

Chapter Forty-Four

A prophecy was just a set of words, Jezebel told…

Chapter Forty-Five

Jezebel called for Beset, who summoned the commander of the…

Chapter Forty-Six

Down in the stableyard, several horses were already harnessed and…

Chapter Forty-Seven

Messengers were dispatched to Samaria, Tyre and Jerusalem to spread…

Chapter Forty-Eight

The coronation was set for the following day, and from…

Chapter Forty-Nine

Throughout the coronation ceremony, Jezebel kept looking around the fringes…

Chapter Fifty

The Palace was full of noise that evening, but Jezebel…

Two years later 852 BC – Queen Mother

Chapter Fifty-One

The spring sunshine brought a light breeze with it, and…

Chapter Fifty-Two

Beset dropped her spoon on the platter, a dull thud…

Chapter Fifty-Three

Shadows from the lamp danced on the walls of Jezebel’s…

Chapter Fifty-Four

A terrible pall of silence had fallen over Samaria after…

Chapter Fifty-Five

‘It’s too dangerous,’ said Daniel, as Jezebel stood on the…

Chapter Fifty-Six

Jezebel’s melancholy was infectious. She and Raisa sat for a…

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Even after a month, Jerusalem still felt like a foreign…

Chapter Fifty-Eight

It wasn’t Athaliah who called on Jezebel the next day.

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Without the protection of her anonymity in Jerusalem, Jezebel found…

Chapter Sixty

Five days later Jezebel received word that Joram had returned…

Ten years later 842 BC – Jezebel

Chapter Sixty-One

The tiny stone house in the corner of the Palace…

Chapter Sixty-Two

Jezebel rode out to meet the carriage that brought Joram…

Chapter Sixty-Three

Once again it was Ahaziah who spotted the arrival of…

Chapter Sixty-Four

Jezebel blinked in the darkness, unsure at first what had…

Epilogue

Who will stop and drop a coin to hear the…

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Other Books by Eleanor de Jong

About the Publisher

Map

Chapter One

Salt spray glistened in the stallion’s mane and stung Jezebel’s cheeks. She leaned close into the neck of the horse, urging the animal on through the low waves. Ahead, the city of Tyre rose up out of the lapis blue of the Great Sea, the white walls of the Royal Palace and the temples like the crest of a perfect wave just ready to break.

As Jezebel reached the causeway that climbed onto the lower reaches of the Tyrian island, Shapash the sun Goddess had already begun to draw her heavy head towards the soft shoulder of Yam, the God of the sea. Jezebel knew she should turn south at the city gates, towards the Palace and the stables. Rebecca, her maid, would be waiting to tut and sigh at how the young princess had surrendered her carefully arranged elegance for the dishevelled disarray of any other fifteen-year-old girl let loose for an afternoon.

But Jezebel couldn’t resist one last whip of the wind in her hair and instead turned north, daring the horse faster and faster round the city walls. She galloped out along the narrow stone promontory, built on the orders of her father to protect the harbour from the heaving discontent of winter seas. For a moment, she felt like she was flying, until the stallion tensed beneath her, his ears pricked and eyes wide. He shuddered to a halt. Jezebel grabbed at the harness to steady them both, her knees digging hard into the saddle cloth. ‘Steady, boy!’

The promontory fell away steeply on either side, the sheer walls plunging deep into the natural well that Tyrian ships called home. For a moment she felt dizzy, as though the tide was rising fast to meet her, and she laughed in spite of the unexpected rush of fear, and patted the horse’s neck. ‘Don’t you dare tell Father I brought you out here.’

She glanced back along the wall but they were quite alone up here. A large crowd had gathered below on the wooden docks that nestled into the curve of the harbour, their attention entirely on a wedding party disembarking from small redwood boats. Snatches of pipe music and laughter drifted up. Jezebel spotted a girl of about her own age stepping off the boat, her hands taken up by a young man. They both wore the plain linen tunics favoured by fishing families, but the young man wore a second overskirt, a shenti in rich Tyrian purple. Jezebel’s older brother Balazar wore the same type of garment – if somewhat more bejewelled – every day as he strutted the enclosed gardens of the Royal Palace. Jezebel guessed this young man must be one of the fishermen whose rare right to wear the purple cloth came from the back-breaking daily grind of harvesting the precious sea snails that gave up the dye. His bride was lucky to marry such a man, for if she could ignore the terrible smell of the rotting snails he must endure to make the dye, and if he could rise up steadily from fisherman to trader, perhaps one day he would sail her in a much larger boat down the coast to Ashdod or even as far as Egypt.

The crowd cheered as the young man draped a fine purple veil over his bride’s hair, and beneath Jezebel the horse grew restless. She shivered and glanced towards the setting sun.

‘Father will be expecting us,’ she said quietly.

She turned the horse around where the wall widened and let it trot back into the city. But she could not resist a last look down at the wedding party. The dock was now edged by the sparkle of shell lamps. The girl looked so happy as her husband fastened a purple-edged cape at her throat. Jezebel’s hand reached absently to her own throat and the fat Red Sea pearls that rested on her skin. Perhaps Rebecca would know who the happy couple were, perhaps they were young cousins of hers and she would be able to tell their story. The island was full of faces Jezebel recognised and who would smile respectfully when they saw their princess ride by, but whose names only Rebecca could know.

Though when she sees me like this, Jezebel thought, I doubt if she will ever speak to me again.

Chapter Two

There was indeed a faintly frosty welcome when she returned to the stables, not from Rebecca but from Hisham, one of her father’s senior courtiers.

‘I must be in trouble if Father has sent you to find me,’ she said as she handed the harness to one of the stable boys.

Hisham’s lips barely curved. ‘His Royal Highness has been waiting two hours.’

‘I suppose Balazar has told on me. Otherwise, how would you have known where to find me?’

‘The King had also hoped to ride this afternoon, Your Highness.’

‘Oh.’ Jezebel winced and glanced at her father’s favourite stallion, now being rubbed down by the boy. ‘I don’t suppose I have time to change my dress either, do I?’

‘I believe there will be time for that in due course.’

Hisham turned neatly on his sandalled feet, and led Jezebel through the Palace to her father’s retiring room at a ridiculously stately pace considering the apparent urgency.

‘You look a mess,’ said Balazar from where he lay on the couch beside her father’s marble desk. King Ithbaal was sitting at the desk studying a scroll of papyrus that rustled crisply as his fingers worked across it. He did not look up at the sound of his son’s voice and Jezebel chewed on her lip. The desk was piled high with scrolls, some of them papyrus, others of vellum, and a neat pile of engraved clay tablets stood on one corner. Jezebel tucked her loose hair behind her ears.

‘At least I’ve not just been lying around.’

‘Don’t we have boys to exercise the horses?’ yawned Balazar, twisting his black hair between his short fingers. ‘Anyway, you should not go out on your own like that. I could see you racing along the beach from up here. It’s not safe.’

‘Or seemly?’ she asked. ‘When was the last time you even stepped out of the Palace? In all your seventeen years, have you ever been across the causeway?’

‘I have no need to go down there. Anyone of note comes to us, Jezebel.’

Ithbaal let the scroll close around his hand. ‘And did you see anyone of note on your ride today, my dear?’

She walked to the desk and kissed his cheek. ‘I’m sorry. Will you forgive me? You should have told me at lunch that you wanted to ride. We could have gone together. I would even have let you saddle your own horse.’ She maintained a pious expression for a moment, then smiled, for her father’s dark eyes sparkled with amusement.

‘Actually, we could have ridden out together to meet the Judeans,’ he said. ‘I am surprised you did not see their retinue on the Sea Road.’

‘I thought they weren’t coming for a few days.’ Jezebel pushed back one end of the scroll which her father had been reading. The angular letters were neatly inscribed, but they were so tiny and ran on and on. But still she read, lowering her head towards the scroll: Tax on goods in transit— Contribution to maintenance of the King’s Highway—

She let the scroll go. ‘Are you asking the Judeans to pay for the upkeep of the northernmost stretch of the Highway? They surely will not agree to that. It is the furthest stretch from Judah, and also the furthest from here, and the part of the Highway in which both kingdoms have least interest.’

‘Are you calling Father a fool?’ asked Balazar lazily from the couch.

‘Jezebel is right. Strategically it appears to make little sense.’ Ithbaal looked down at his son.

‘Then it makes little sense,’ repeated Balazar, his cheeks ruddying.

‘Unless you think that Ben-Hadad of Damascus has ambitions to seize that piece of the Highway,’ explained Jezebel. ‘It borders his land of course. Should it fall into his hands traders would be at his mercy. That does neither Judah nor Tyre and Sidon any good at all.’

Ithbaal nodded, but his attention had fallen from her face to her dress. ‘I presume you have something else to wear for dinner. One of your very best outfits. And perhaps that engraved amethyst pendant I gave you for the Spring Festival.’

‘You want me to meet the Judean officials?’

‘They’re absolute barbarians,’ said Balazar. ‘No culture, no art, their food is bland, and that awful brown land—’

‘I suppose I’ll seat you between the King’s son Jehoshaphat and his son Jehu,’ said her father to her, resting his hand on her shoulder. He spoke casually, but she felt the weight of his touch. ‘I am sure you will show them both the very best of your hospitality.’

Jezebel’s heart banged hard in her chest, and she held her breath to slow it down. ‘Of course, Father.’

Her father stood and walked away without another word and Jezebel could only watch him go, as dizzy now as she had been up on the promontory.

‘You know what he means, don’t you,’ said Balazar slyly, ‘sitting you next to—’

‘I know.’

She ran past Hisham out of the retiring room and up the grand stone staircase to her room, flinging back the heavy drapes and darting across the corner of the room to the small shrine to the great Goddess Astarte beside the east window. But the stone plinth was already heaped with grapes, and the redwood circle carved with Astarte’s manifestations was wound with fresh tendrils and leaves of the vine.

Jezebel glanced frantically around the room, for Astarte’s shrine was only ever dressed for festivals and for weddings. At the foot of the bed stood Rebecca, her hands clasped at her waist, her eyebrows arched knowingly beneath her greying hair. Beside her was her youngest daughter, Beset, a year older than Jezebel and in Palace service at her mother’s side. The girl smiled at Jezebel. Jezebel tried to speak, but her throat was tight and she could only sink down onto the white kneeler at the foot of the shrine. At a nod from Rebecca, Beset filled Astarte’s ceremonial bowl with water and gave it to Jezebel. She drank it down gratefully.

‘What did Father tell you?’ she whispered, looking up at her maids. ‘You must know something, else why would you have dressed the shrine?’

‘So that Astarte will guide you,’ said Rebecca.

‘I will have to marry one of these Judeans to secure the safety of the Highway,’ gulped Jezebel. She’d been expecting this day for two years – not many royal daughters remained unmarried in their sixteenth year. ‘Has he told you which one?’

‘The Palace is full of gossip—’ whispered Beset.

‘Then which?’

‘It won’t do us any good to speculate,’ said Rebecca, frowning at her daughter. ‘We have made our offering to the Goddess, so we must allow her to take care of you.’

Jezebel shook her head. ‘It would surely be better if I did not understand what is at stake, then I could just do as I am told without thinking about it.’

‘When have you ever done as you are told?’ said Rebecca. ‘Now come and bathe and then we can dress you. You must look your best for your future husband, whomever the Fates decide upon.’

Chapter Three

Later that evening, Jezebel entered her father’s crowded chambers for the ceremonial dinner, her heart feeling tight in her chest. Two courtiers held the pleated train of her finest silk dress, and she kept her eyes fixed on her father rather than glancing around at what form her future might take. Ithbaal stood to escort her personally to the couch opposite his, signalling the respect which she was to be accorded by the visitors. Jezebel lowered her gaze to the tables, groaning beneath golden bowls piled high with cooked grains and meat, fruits and nuts.

‘You look wonderful,’ whispered her father.

Jezebel concentrated on keeping her shoulders drawn back. Standing so, she was almost as tall as her father. Her shoulders were bare, and almost brushed by the amethyst pendants of her earrings. Rebecca had wanted to whiten her skin, but Jezebel hated being pasted with make-up, especially when it was liable to crack as the evening wore on. She settled for a pearlescent shimmer dusted across her collar bones. Her lips were painted vermillion, using one of her mother’s recipes learned from the Egyptians.

‘I had always thought it like the cool of a midnight sky,’ said a voice to her right, ‘but in truth it is more like the heat of a glorious sunset.’

‘I’m sorry?’ said Jezebel politely, turning. The accent was not like any she had heard before.

‘Tyrian purple,’ said a young man settling on the couch next to her. From Balazar’s dismissive description, Jezebel had imagined the Judeans to be as dull and ugly as their lands, but this fellow was as handsome as any of the young men of Tyre. His jaw was a little squarer and his eyes had a dark knowing about them that Jezebel found oddly cool in their attractive setting. From his unlined face, he might have been only a couple of years older than her, perhaps even eighteen, but his body was certainly a man’s. She blushed at how intently he studied her in return. His eyes caressed her shoulders, then took in the folds of fabric that draped across her body. ‘The cloth I’ve seen dyed with it in the Jerusalem markets has a rather bluer hue to it,’ he continued, ‘but your dress is quite rich and red in comparison.’

There was a moment’s silence before Jezebel realised he was expecting an answer, but when she tried to speak, no words would come. The Hebrew he spoke was guttural but soft. She coughed, her fingers covering her mouth, and the young man quickly reached for a bowl of wine and offered it to her.

‘Thank you,’ she whispered, furious with herself for being so struck by his looks that she had forgotten her poise and her manners. She drank some wine, and swall owed hard. ‘I’m afraid that the colour you are describing isn’t true Tyrian purple, but tekhelet.’

‘I don’t know this word,’ he said, ‘what does it mean?’

Jezebel swallowed some more wine, its richness surely flushing her cheeks even more. ‘Tekhelet is the colour used for our ritual clothing.’

‘And that makes it different?’

Jezebel lowered her gaze. ‘I am quite sure one of the officials will be able to tell you about the technical processes if you wish to know.’

He leaned closer to her and she smelled the sweet almond oil on his hair. ‘It can be very boring,’ he whispered, ‘listening to a lot of officials droning on. But I’m sure the Princess Jezebel can make even a dead snail sound interesting.’

‘It seems you know more about me than I know about you,’ said Jezebel. ‘I’m afraid I don’t even know your name.’

The young man lowered his head and hesitantly offered his hand, palm up, in the traditional Phoenician greeting. Jezebel lowered her palm onto his in response, the calluses at the base of his fingers catching on her own smooth soft skin.

‘I apologise. A soldier’s hands are not as soft as a princess’s,’ he said. ‘I’m Jehu, the youngest in the Judean line. My father, Jehoshaphat, sits to your left. My grandfather Asa sits between your brother and your father.’

Jehoshaphat had turned towards the sound of his name, and she offered her hands for the greeting. The father’s jaw had the same hard contour as the son’s but his mouth lacked fullness and his eyes were hawkish. He glanced contemptuously at Jezebel’s hands, then turned his attention back to Balazar. King Asa was a small man with bright eyes and just a scattering of hairs across his liver-spotted scalp. Most of his fingers bore thick gold rings, and he threw a mischievous smile towards her, as if to say ‘Were I a younger man …’