Полная версия:

The Crown of Dalemark

Copyright

First published in Great Britain by Mandarin in 1993

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is www.harpercollins.co.uk

Copyright © Diana Wynne Jones 1993

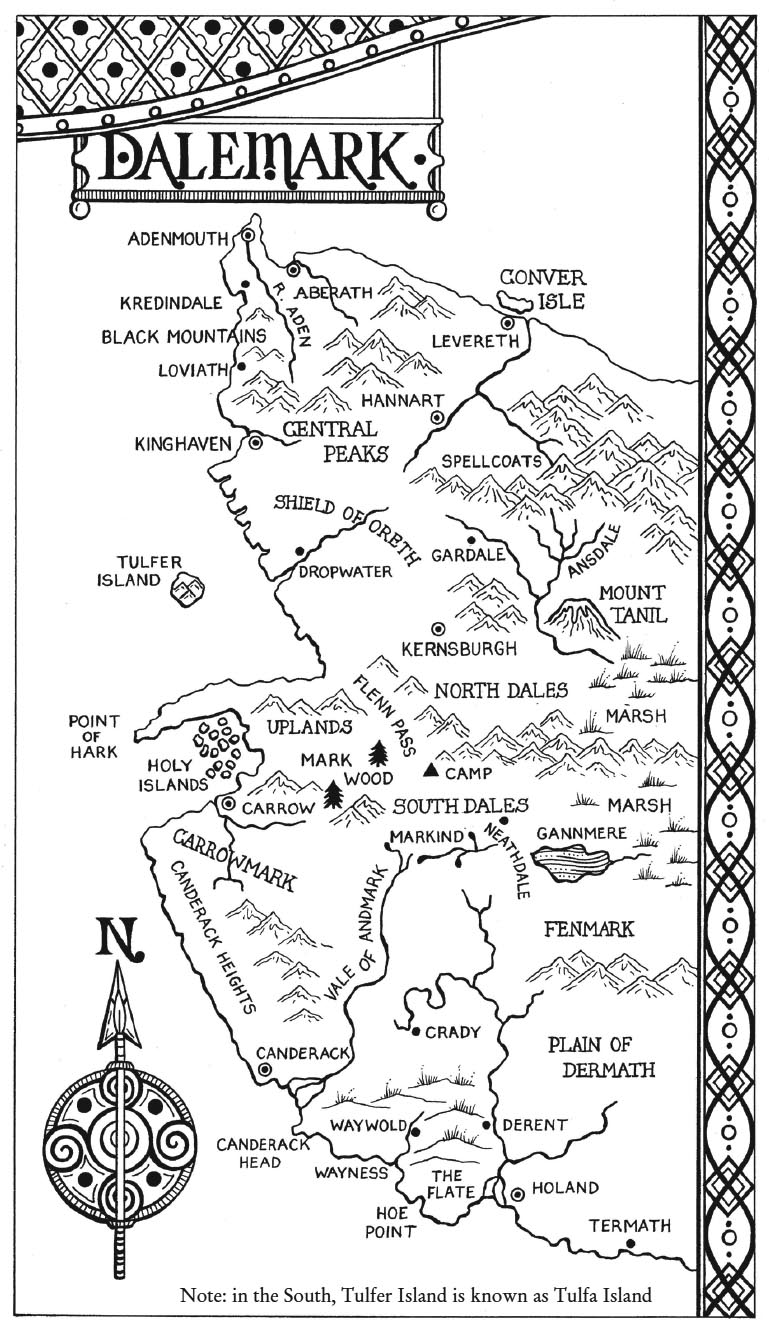

Map illustration © Sally Taylor 2017

Cover artwork © Manuel Šumberac

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Diana Wynne Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008170714

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780008170721

Version: 2016-11-25

For Rachel

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Map of North and South Dalemark

PART ONE: Mitt

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

PART TWO: Maewen

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

PART THREE: Ring and Cup

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

PART FOUR: Sword and Crown

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

PART FIVE: Kankredin

Chapter Twenty-Two

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Books by Diana Wynne Jones

About the Publisher

Map of North and South Dalemark

THE EARL OF HANNART arrived in Aberath two days before Midsummer. He was bringing the Countess of Aberath a portrait of the Adon to put in her collection. As this was a state visit, he brought his son as well and a string of his hearthmen, and his arrival caused a rare bustle.

A tall man dressed like a shepherd watched it all from high in the hills where the green roads ran. He had an excellent view from there, not only into the seething courts of the mansion but of the whole town, the cliffs, the bay and the boatsheds. The Earl was easy to pick out among the hurrying figures, because he was with a servant carrying the picture. The man watched them go straight to the library, where he knew the Countess was waiting to receive the Earl. Almost immediately the servant was sent away to fetch someone else. The watcher could see him pushing his way, first to the stables, then to the dining hall, and finally to the hearthmen’s quarters, where he fetched out a large gangly person and pointed to the library. The gangly one set off there at a run, on long, gawky legs.

The watcher turned away. “So they did send for this Mitt,” he said as if this had confirmed his worst suspicions. Then he looked up and round and over his shoulder, clearly thinking that someone else was standing nearby, watching too. But the green road was empty. The man shrugged and set off walking swiftly inland.

About the same time as this man left, Mitt arrived at the top of the library steps, trying not to pant, and pushed open the creaky door.

“Oh, there you are,” said the Countess. “We want you to kill someone.”

She was never one to beat about the bush. It was almost the only thing Mitt liked about her. All the same, he wondered if he had heard her right. He stared at her long, bony face, which was set slightly crooked on her high shoulders, and then looked at Earl Keril of Hannart to make sure. Mitt had been ten months now in Aberath, but the North Dalemark accent there still sometimes made him hear things wrong. Earl Keril was dark, with a long nose. Everyone said what a likeable man he was, but he was looking at Mitt as grimly as the Countess.

“Didn’t you hear?” Earl Keril asked. “We want someone dead.”

“Yes. Is this a joke of some kind?” Mitt said. But he could tell from their faces that it was not. He felt cold and disgusted, and his knees shook. “I gave up killing – I told you!” he said to the Countess.

“Nonsense,” she said. “Why else do you think I had you trained as my hearthman?”

“You would have it that way, not me!” Mitt said. “And I never kidded myself you made me learn all that out of love for me!”

Earl Keril looked questioningly at the Countess.

“I warned you he was rude,” she said. She leant towards him, and they murmured together.

Mitt was too disgusted to try to overhear. He looked beyond their two implacable faces at the painting of the Adon propped on an easel behind them. The light was across the canvas from where Mitt stood, in a bluish haze, but the painted eyes caught his, like dark holes in the haze. They looked ill and haunted. The famous Adon had been far from handsome, sickly-looking, with lank hair and crooked shoulders. Near on a cripple, like the Countess, Mitt thought. She and Earl Keril both descended from the Adon. She had the shoulders; Keril had the Adon’s long nose. Earlier that day Mitt would have been thoroughly disappointed to find that the Adon looked like this. Since he came to Aberath, he had heard story after story of the Adon, the great hero who had talked with the Undying and lived as an outlaw before he became the last King of Dalemark several hundred years ago. Now he looked from the painting to the two living faces leaning together in the twilight of the library, and he thought, Fairy stories! Bet he was just as bad as they are! Well, I ran off from Holand, so I reckon I can run off from Aberath too.

Just then he caught a murmur from Keril. “Oh, yes, I’m sure that he is!” Sure I am what? Mitt wondered as they both looked at him again. “We’ve gone into your history,” Keril said to him. “Attempted murder in Holand. Successful murder in the Holy Islands—”

“That’s a lie!” Mitt said angrily. “Whatever you think, I never murdered a single soul! And I gave up trying long before I came here.”

“Then you’ll have to force yourself to try again,” said the Countess. “Won’t you?”

“And you came on here by boat,” Keril went on, before Mitt could speak, “with Navis Haddsson and his children Hildrida and Ynen. In Aberath the Countess took you in and had you educated—”

“For my sins,” the Countess said unlovingly.

“So you see the North has treated you well,” Earl Keril said. “Better than most refugees from the South, in fact, both you and your friends. We found Navis a post as hearthman to Stair of Adenmouth, and we sent Hildrida to study at the Lawschool in Gardale. Have you ever wondered why this was?” As Mitt wondered about it, Keril added pleasantly, “Why the four of you were separated in this way, I mean.”

It was a pleasantness that made Mitt feel like a sack with a hole in it. Everything trickled away through the hole, and his knees almost let him down. “Where’s Ynen then?” he said. “Isn’t he with Navis?”

“No,” said the Countess. “And we are not telling you where he is.”

Mitt watched her long jaw shut like a trap. “I used to think,” he said, “that the earls in the North were good. But you’re as bad as the ones in the South. Go to any lengths, all of you! You’re telling me to kill someone for you or my friends suffer. Right?”

“Let’s just say – if you want to see your friends again,” Keril suggested.

“Well, you’re wrong,” Mitt said. “You can’t make me do anything. I don’t care two hoots for any of them.”

The two implacable faces just looked at him.

Mitt managed a careless shrug. “We happened to ride on the same boat, that’s all,” he said. “I swear it.”

“You swear it? By which of the Undying?” Keril asked. “By the One? The Piper? The Wanderer? She Who Raised the Islands? The Weaver? The Earth Shaker? Come on. Choose which and swear.”

“We don’t swear like that in the South,” said Mitt.

“I know,” said Keril. “So it won’t hurt you to swear to me by the Earth Shaker that Navis and his children mean nothing to you. Just swear, and we’ll forget the whole matter.”

Their faces tilted towards Mitt. Mitt looked away, at the dark painted eyes of the Adon, and tried to make himself swear. If Keril had chosen any other of the Undying, he thought he could have done it easily. But not the Earth Shaker. And that showed how frighteningly much Keril knew. Even so, perhaps he could swear about Navis and Hildy and let on he meant Ynen too? Navis, cold fish on a slab that the man was, still didn’t seem to like Mitt particularly; and as for Hildy, after her last letter, Mitt could almost swear he hated her. But he had shown he was worried about Ynen, like a fool, and there was no way he could even pretend to dislike Ynen or let these two earls hurt him.

“Is Ynen all right?” he said.

“Perfectly, at the moment,” said the Countess. She never told lies. Mitt was relieved, until he realised that she and Keril both had the same look, satisfied and unsurprised. They knew he had given in. They had expected it.

“I warn you,” Mitt said, “if there’s murdering needing doing, I can see two ripe cases for it here in this room. So who do you want killed? What’s so special that you need to go to all this trouble with me to have it done?” Keril’s eyebrows went up. The Countess seemed surprised. Good, Mitt thought. Find out how important it is from how rude they let me be. “Do you take me for a fool?” he said. “If it was lawful, you both have lawyers to burn, and if it was ordinary, you’ve hearthmen to do it by hundreds. And I’d lay good money you have spies and murderers better than me any day. So it stands to reason it must be politics – you wanting to lay this on Southern scum like me.”

“You said it, not me,” Keril replied. “Politics, it is. We want a young lady out of the way. She’s very charming and much too popular. The whole of the west coast, including Dropwater, will follow her as soon as she gives the word.”

“Flaming Ammet!” protested Mitt.

“Be quiet!” said the Countess. “Listen!” She said it like the snap of a steel trap. End of rudeness, thought Mitt, and swallowed what he had been going to say. It hurt, as if he had swallowed an apple whole.

“Noreth of Kredindale, known as Onesdaughter,” Keril said. “I expect you’ve heard of her.” Mitt shook his head, but it was from amazement, because he had indeed heard of Noreth Onesdaughter. The story of the One’s only human child was one of the many, many stories he had heard round the small coal fires in Aberath this last winter. He had thought that like other stories, it was from times long ago. But Keril, in the most matter-of-fact way, went on to speak of Noreth as alive here and now. “Unfortunately,” he said, “she’s extremely well connected. The Kredindale family go back to the Adon’s daughter Tanabrid, whose mother was of the Undying. Noreth is cousin to Gardale and Dropwater – though Stair’s wife at Adenmouth is the aunt who brought her up – and she’s a distant cousin of mine too—”

“And mine,” said the Countess. “Pity the girl’s mad.”

“Mad or not,” said Keril, “Noreth claims that her father is the One himself. As her mother died when Noreth was born, there’s no one to contradict her, and this claim gives her a huge following among the ordinary people. She makes no secret that she thinks she’s born to become Queen of all Dalemark – North and South.”

“And that fool in Dropwater backs her,” said the Countess.

So that’s it! Mitt thought. They’re scared for their earldoms. So they get me to stop her and then blame it on the poor South! “Just a minute,” he said. “If she’s who she says she is, no one can do a thing about it. And someone who’s from the Undying on both sides isn’t going to be easy to kill either.”

“Quite possibly,” Keril said. “That’s why we were so interested in what we heard about you from the Holy Islands. Reports from there suggested that you could well ask the Undying to help you.” Mitt stared at him, shocked at how much Keril knew and how coldly he was prepared to use that knowledge. Keril leant forwards. “We don’t want yet another false king and yet another ruinous uprising,” he said. Mitt saw he really meant it. “We don’t want another war with the South. We want Noreth quietly stopped before she can lay her hands on the crown.”

“The crown?” said Mitt. “But nobody knows where that is. They tell stories here about how Manaliabrid hid it.”

“She did,” said Keril.

“Noreth,” said the Countess, “says that the One will show her where it is.” Mitt looked from one face to the other and suspected both of them had a fair idea where the crown was hidden. “The girl claims the One talks to her,” the Countess added disgustedly. “I told you she was mad. She says the One has promised her a sign to prove her claim and that this year at Midsummer she will become Queen. Silly nonsense.”

“She’s in Dropwater at the moment,” Keril said, “acting as law-woman for her cousin, but our information is that she’ll be going to her aunt in Adenmouth for Midsummer to drum up support there. We’re sending you to Adenmouth too.”

“And,” said the Countess, “you’re to go there and stop her. But don’t do it there. We want this quiet.”

“We advise you to join her as a follower – you shouldn’t be noticed among all the others – and then look for a suitable opportunity,” Keril said. As Mitt opened his mouth, he added, “If you want to see Hildrida and Ynen again, you will.”

“But Midsummer’s the day after tomorrow!” Mitt protested. A stupid thing to say, but he had been looking forward to the feasting in Aberath.

“It’s an easy day’s ride,” said the Countess, who rarely went anywhere except by carriage. “I shall give out that you have my leave to go and visit Navis Haddsson in Adenmouth. You will go first thing tomorrow. You may go away and pack now.”

Mitt had been taught that you bowed on leaving the presence of an earl, but he was too disgusted to remember. He turned and blundered his way across the dimness of the library, past the books and the glass cases that held the Countess’s collection: the necklace that was supposed to have been worn by Enblith the Fair, the ring that once belonged to the Adon, a flute of Osfameron’s, and the withered piece of parchment that went back to the days of King Hern. Behind him he sensed the two earls drawing themselves up in indignation.

“Mitt Alhamittsson,” said Keril. Mitt stopped and turned round. “I remind you,” Keril said, “that a man can be hanged when he is fifteen. They tell me your birthday is the Autumn Festival. Noreth had better be dead before then, hadn’t she?”

“Or we may not be able to avert the course of justice,” added the Countess. “You have nearly three months, but don’t cut it too fine.”

So there was no possibility of putting things off. “Yes,” said Mitt. “I get you.” He looked past them to the harrowed, ill-looking face of the Adon. He could see the portrait better from here. He pointed his thumb to it. “Miserable-looking blighter, isn’t he?” he said. “It must be giving him a right bellyache having you two as descendants!” Then he turned round and walked to the door, rather hoping he had been rude enough to be thrown into prison on the spot. But there was no sound behind him while he opened the door, and no sound but the groan of the hinges as the door shut on his heels. The man on guard outside straightened up guiltily and then relaxed when he saw it was only Mitt. Mitt marched away down the steps without speaking to him. They really meant him to kill this girl. Even the Countess had not told him off for his rudeness.

His knees were trembling as he came out into the courtyard. He almost wanted to cry with shame. It was the way Keril had muttered “Oh, yes, I’m sure he is!” that seemed to have got to him most – sure Mitt was a guttersnipe, a Southerner with no feelings, the first person earls turned to when they wanted dirty work done. Mitt had known such a person and vowed never to be like that, but a fat lot those two cared!

Someone shouted to him across the courtyard.

A knot of people stood there, all about his own age. Earl Keril’s son, Kialan, was one of them, and the others were waving to Mitt to come over. Mitt had been rather anxious to meet Kialan. Now he found he could not bear to. He ducked sideways and turned along the wall.

“Mitt!” shouted Alla, the Countess’s bronze-haired daughter. “Kialan wants to meet you!”

“He’s heard all about you!” shouted Doreth, the copper-haired daughter.

“Can’t stop! Message! Sorry!” Mitt shouted back. He did not want to meet the daughters either. Alla had jeered at him for being so miserable when Hildy was sent away, until Mitt got mad and pulled her bronze hair. Then Doreth had told the Countess on him. Mitt had been quite surprised not to be sent away then too. But that must have given them proof that Mitt did care what became of Hildy. Flaming Ammet! The Countess and Keril must have had this planned for months!

Kialan was now shouting himself. “See you later, then!” Mitt had a glimpse of him waving, tawny and thickset and quite unlike his father – but quite certainly not really unlike, not deep down where it counted. Mitt put his head down and sped along by the wall, wondering if Kialan saw him as a dirty Southern guttersnipe too. Kialan would certainly see a lot of lank hair and two spindly legs and shoulders that were too wide for the rest. Mitt kept his face turned to the wall because that was the real giveaway, a guttersnipe face that still looked starved even after ten months of good food in Aberath. He told himself Kialan wasn’t missing much.

He plunged through the nearest door and kept running, through rooms and along corridors, and out again on the other side of the mansion, to the long shed on the cliffs above the harbour. That was the best place to be alone. The people who were usually there would all be rushing about after Keril’s followers or getting the Midsummer feast ready. And he was having to miss that feast. Hildy had once said that misery was like this: silly little things always got mixed up with the important ones. How right she was.

Mitt rolled the shed door open a crack and slipped inside. Sure enough, the place was empty. Mitt breathed deep of the fishy smell of coal and of fish oil and wet metal. It was not unlike the smell on the waterfront of Holand, where he had been brought up. And I might just as well have stayed there for all the good it did me! he thought, staring along a vista of iron rails in the floor, where tarry puddles reflected red sun or rainbows of oil. He felt caught and trapped and surrounded in a plot he had not even noticed till they thrust it at him this afternoon. Everyone had told him that the Countess was treating him almost like a son. Mitt had been pretty sarcastic about that, but all the same he had thought this was the way people in the North did treat refugees from the South.

“Fool I was!” he muttered.

He walked along the rails to the huge machines that stood at quiet intervals along them. Alk’s Irons, everyone called them. To Mitt, and to most people in town, they were the most fascinating things in Aberath. Mitt trailed his fingers across the cargo hoist and then across the steam plough and the thing that Alk hoped might one day drive a ship. None of them worked very well, but Alk kept trying. Alk was married to the Countess. It was the only other thing Mitt liked about the Countess: that instead of marrying the son of a lord or another earl who might add to her importance, she had chosen to marry her lawman, Alk. Alk had given up law years ago in order to invent machines. Mitt dragged his fingertips across the wet and greasy bolts of the newest machine and shuddered as he imagined himself pushing a knife into a young woman. Even if she laughed at him or looked like Doreth or Alla, even if her eyes showed she was mad – no! But what about Ynen if he didn’t? The worst of this trap was that it pushed him back into a part of himself he thought he had got out of. He could have screamed.

He went round the machine and found himself face to face with Alk. Both of them jumped. Alk recovered first. He sighed, put his oilcan down on a ledge in the machine, and asked rather guiltily, “Message for me?”

“I – No. I thought nobody was here,” Mitt said.

Alk relaxed. To look at him, you would have thought he was a big blacksmith run to fat, with his mind in the clouds. “Thought you were calling me to come and run about after Keril,” he said. “Now you’re here, have a think about this thing. It’s supposed to be an iron horse, but I think it needs changing somewhere.”

“It’s the biggest horse I ever saw,” Mitt said frankly. “What good is it if it has to run on rails? Why do your things always run on rails?”

“To move,” said Alk. “Too heavy otherwise. You have to work the way things will let you.”

“Then how are you going to get it to go uphill?” said Mitt.

Alk rubbed an oily hand through the remains of copper hair like Doreth’s and looked sideways at Mitt. “Boy’s disillusionment with the North now complete,” he said. “Taken against my machines now. Anything wrong, Mitt?”

In spite of his trouble, Mitt grinned. Alk and he had this joke. Alk himself came from the North Dales, which Alk claimed were almost in the South. Alk said he saw three things wrong with the North for every one that Mitt saw. “No, I’m fine,” Mitt said, because the Countess had probably told Alk all about her plans anyway. He was trying to think of something polite to say about the iron horse when the door at the end of the shed rolled right open. Kialan’s strong voice came echoing through.

“This is the most marvellous place in all Aberath!”

“Excuse me,” Mitt muttered, and dived for the small side door behind Alk.

Alk grabbed his elbow as he went. He was as strong as the blacksmith he looked like. “Wait for me!” he said. They went out of the side door together, into the heap of coal and cinders beyond. “Taken against the Adon of Hannart too, have you?” Alk asked. Mitt did not know how to answer. “Come up to my rooms,” Alk said, still holding Mitt’s elbow. “I have to dress grandly for supper, I suppose. You can help. Or is that beneath you?”