Полная версия:

The Girl with Seven Names: A North Korean Defector’s Story

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

First published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2015

This William Collins paperback edition published 2016

Copyright © Hyeonseo Lee 2015

Hyeonseo Lee asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

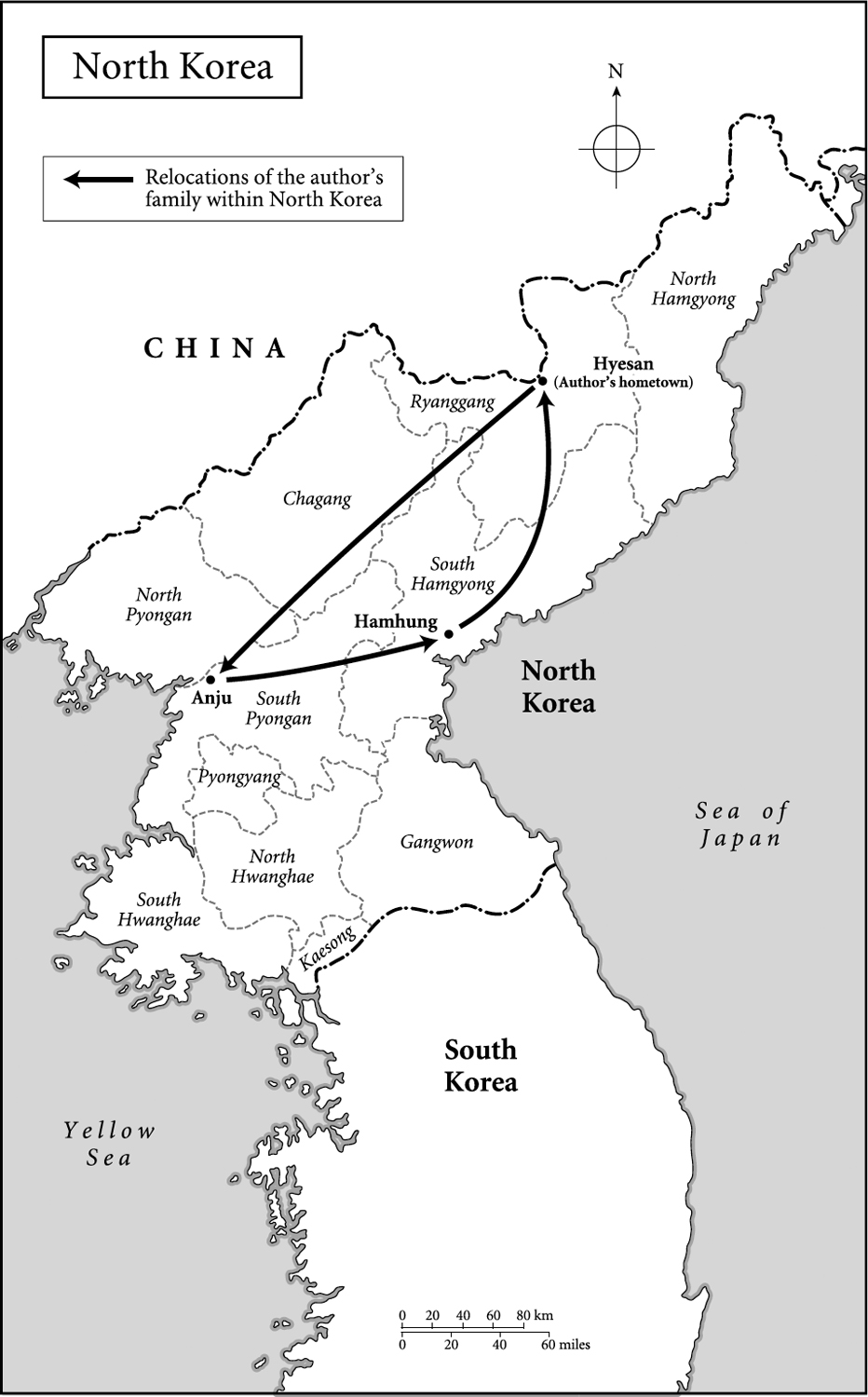

Maps by John Gilkes

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007554850

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 9780007554867

Version: 2016-03-02

Praise for Hyeonseo Lee:

‘Stirring and brave … true, committed, unvarnished and honest. Lee has made her own life the keyhole to the present, inside and outside of North Korea’ Scotsman

‘Remarkable bravery fluently recounted’ Kirkus

‘Hyeonseo Lee brought the human consequences of global inaction on North Korea to the world’s doorstep … Against all odds she escaped, survived, and had the courage to speak out’

Samantha Power, US representative to the United Nations

‘I have spoken with countless numbers of defectors over the years. When I first met Hyeonseo Lee, the unflinching manner in which she told her story, although full of sadness and hurt, was inspirational. That is the story now written in this book … Every time she navigated treacherous terrain and overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles, she had to change her name to protect her new identity. She became the Girl with Seven Names … But one thing that she held on to was her humanity, ever stronger as she continuously sublimated her hardships into hope’

Jang Jin-sung, founder of New Focus International and author of Dear Leader: Poet, Spy, Escapee – A Look Inside North Korea

‘This is a powerful story of an escapee from North Korea. In the hallowed meeting rooms of the United Nations in New York, ambassadors from North Korea recently sought to shout down stories like this. But these voices will not be silenced. Eventually freedom will be restored. History will vindicate Hyeonseo Lee and those like her for the risks they ran so that their bodies and their minds could be free. And so that we could know the truth’

The Honourable Michael Kirby, Chair of the UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights Abuses in North Korea, 2013–14

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PRAISE

MAPS

AUTHOR’S NOTE

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

Part One: The Greatest Nation on Earth

1. A train through the mountains

2. The city at the edge of the world

3. The eyes on the wall

4. The lady in black

5. The man beneath the bridge

6. The red shoes

7. Boomtown

8. The secret photograph

9. To be a good communist

10. ‘Rocky island’

11. ‘The house is cursed’

12. Tragedy at the bridge

13. Sunlight on dark water

14. ‘The great heart has stopped beating’

15. Girlfriend of a hoodlum

16. ‘By the time you read this, the five of us will no longer exist in this world’

17. The lights of Changbai

18. Over the ice

Part Two: To the Heart of the Dragon

19. A Visit to Mr Ahn

20. Home truths

21. The suitor

22. The wedding trap

23. Shenyang girl

24. Guilt call

25. The men from the South

26. Interrogation

27. The plan

28. The gang

29. The comfort of moonlight

30. The biggest, brashest city in Asia

31. Career woman

32. A connection to Hyesan

33. The teddy-bear conversations

34. The tormenting of Min-ho

35. The love shock

36. Destination Seoul

Part Three: Journey into Darkness

37. ‘Welcome to Korea’

38. The women

39. House of Unity

40. The learning race

41. Waiting for

42. A place of ghosts and wild dogs

43. An impossible dilemma

44. Journey into night

45. Under a vast Asian sky

46. Lost in Laos

47. Whatever it takes

48. The kindness of strangers

49. Shuttle diplomacy

50. Long wait for freedom

51. A series of small miracles

52. ‘I am prepared to die’

53. The beauty of a free mind

EPILOGUE

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PICTURE SECTION

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

Author’s Note

To protect relatives and friends still in North Korea, I have changed some names in this book and withheld other details. Otherwise, all the events described happened as I remembered or was told about them.

Introduction

13 February 2013

Long Beach, California

My name is Hyeonseo Lee.

It is not the name I was born with, nor one of the names forced on me, at different times, by circumstance. But it is the one I gave myself, once I’d reached freedom. Hyeon means sunshine. Seo means good fortune. I chose it so that I would live my life in light and warmth, and not return to the shadow.

I am standing in the wings of a large stage, listening to the hundreds of people in the auditorium. A woman has just blushed my face with a soft brush and a microphone is being attached to me. I worry that it will pick up the sound of my heart, which is thumping in my ears. Someone asks me if I’m ready.

‘I’m ready,’ I say, though I do not feel it.

The next thing I know I’m hearing an amplified announcement. A voice is saying my name. I am being introduced.

A noise like the sea rises in the auditorium. Many hands are clapping. My nerves begin to flutter wildly.

I’m stepping onto the stage.

I feel terrified suddenly. My legs have turned to paper. The spotlights are faraway suns, dazzling me. I can’t make out any faces in the audience.

Somehow I motion my body toward the centre of the stage. I inhale slowly to steady my breathing, and swallow hard.

This is the first time I will tell my story in English, a language still new to me. The journey to this moment has been a long one.

The audience is silent.

I begin to speak.

I hear my voice trembling. I’m telling them about the girl who grew up believing her nation to be the greatest on earth, and who witnessed her first public execution at the age of seven. I’m telling them about the night she fled across a frozen river, and how she realized, too late, that she could never go home to her family. I describe the consequences of that night and the terrible events that followed, years later.

Twice I feel tears coming. I pause for an instant, and blink them back.

Among those of us who were born in North Korea and who have escaped it, the story I am telling is not an uncommon one. But I can feel the impact it is having on the people in the audience at this conference. They are shocked. They are probably asking themselves why a country such as mine still exists in the world.

Perhaps it would be even harder for them to understand that I still love my country and miss it very much. I miss its snowy mountains in winter, the smell of kerosene and burning coal. I miss my childhood there, the safety of my father’s embrace, and sleeping on the heated floor. I should be comfortable with my new life, but I’m still the girl from Hyesan who longs to eat noodles with her family at their favourite restaurant. I miss my bicycle and the view across the river into China.

Leaving North Korea is not like leaving any other country. It is more like leaving another universe. I will never truly be free of its gravity, no matter how far I journey. Even for those who have suffered unimaginably there and have escaped hell, life in the free world can be so challenging that many struggle to come to terms with it and find happiness. A small number of them even give up, and return to live in that dark place, as I was tempted to do, many times.

My reality, however, is that I cannot go back. I may dream about freedom in North Korea, but nearly seventy years after its creation, it remains as closed and as cruel as ever. By the time it might ever be safe for me to return, I will probably be a stranger in my own land.

As I read back through this book, I see that it is a story of my awakening, a long and difficult coming of age. I have come to accept that as a North Korean defector I am an outsider in the world. An exile. Try as I may to fit into South Korean society, I do not feel that I will ever fully be accepted as a South Korean. More important, I don’t think I myself will fully accept this as my identity. I went there too late, aged twenty-eight. The simple solution to my problem of identity is to say I am Korean, but there is no such nation. The single Korea does not exist.

I would like to shed my North Korean identity, erase the mark it has made on me. But I can’t. I’m not sure why this is so, but I suspect it is because I had a happy childhood. As children we have a need, as our awareness of the larger world develops, to feel part of something bigger than family, to belong to a nation. The next step is to identify with humanity, as a global citizen. But in me this development got stuck. I grew up knowing almost nothing of the outside world except as it was perceived through the lens of the regime. And when I left, I discovered only gradually that my country is a byword, everywhere, for evil. But I did not know this years ago, when my identity was forming. I thought life in North Korea was normal. Its customs and rulers became strange only with time and distance.

Thus I must say that North Korea is my country. I love it. But I want it to become good. My country is my family and the many good people I knew there. So how could I not be a patriot?

This is my story. I hope that it will allow a glimpse of the world I escaped. I hope it will encourage others like myself, who are struggling to cope with new lives their imaginations never prepared them for. I hope that the world will begin, finally, to listen to them, and to act.

Prologue

I was awoken by my mother’s cry. Min-ho, my kid brother, was still asleep on the floor next to me. The next thing I knew our father came crashing into the room, yelling ‘Wake up!’ He yanked us up by our arms and herded us, pushed us, out of the room. My mother was behind him, shrieking. It was evening and almost dark. The sky was clear. Min-ho was dazed from sleep. Outside on the street we turned and saw oily black smoke pouring from our kitchen window and dark flames licking the outside wall.

To my astonishment, my father was running back into the house.

A strange roar, a wind rushing inward, swept past us. We heard a whumpf. The tiles on one side of the roof collapsed, and a fireball like a bright orange chrysanthemum rose into the sky, illuminating the street. One side of the house was ablaze. Thick, tar-black smoke was belching from the other windows.

Where was my father?

Our neighbours were suddenly all around us. Someone was throwing a bucket of water – as if that would quench this blaze. We heard the groan and splitting of wood and then the rest of the roof went up in flames.

I wasn’t crying. I wasn’t even breathing. My father wasn’t coming out of the house.

It must only have been seconds but it seemed like minutes. He emerged, running toward us, coughing his lungs up. He was blackened by smoke, his face glistening. Under each arm he was holding two flat, rectangular objects.

He wasn’t thinking of our possessions, or our savings. He’d rescued the portraits. I was thirteen, old enough to understand what was at stake.

Later my mother explained what had happened. Some soldiers had given my father a large can of aviation fuel as a bribe. The can was in the kitchen, which was where we had an iron stove that burned yontan – the circular charcoal cakes used for heating everywhere in North Korea. She was in the act of decanting the fuel into another container when it slipped from her hands and splashed onto the coals. The combustion was explosive. The neighbours must have wondered what on earth she’d been cooking.

A wall of intense heat was advancing from the blaze. Min-ho began to wail. I was holding our mother’s hand. My father put the portraits down with great care, then hugged the three of us – a public display of affection that was rare between my parents.

Huddled together, watching the remains of our home collapse in a rippling glow, the neighbours might have felt sorry for us. My father looked a sight – his face was filthy and his new civilian suit ruined. And my mother, who was house-proud and always made an effort to dress nicely, was seeing her best bowls and clothes go up in smoke.

Yet what struck me most was that neither of my parents seemed that upset. Our home was just a low, two-room house with state-issue furniture, common in North Korea. It’s hard to imagine now how anyone would have missed it. But my parents’ reaction made a strong impression on me. The four of us were together and safe – that was all that mattered to them.

This is when I understood that we can do without almost anything – our home, even our country. But we will never do without other people, and we will never do without family.

The whole street had seen my father save the portraits, an act of heroism that would win a citizen an official commendation. As it turned out, matters had gone too far for that. We did not know it, but he was already under surveillance.

Chapter 1

A train through the mountains

One morning in the late summer of 1977, a young woman said goodbye to her sisters on the platform of Hyesan Station and boarded the train for Pyongyang. She had received official permission to visit her brother there. She was so excited she’d slept little the night before. The Capital of the Revolution was, to her mind, a mythic and futuristic place. A trip there was a rare treat.

The air was still cool and smelled of fresh lumber from the nearby mill; the humidity was not yet too high. Her ticket was for a window seat. The train set off, creaking slowly southward along the old Hyesan Line through steep pine-clad mountains and over shaded gorges. Now and then a white-water river could be glimpsed far below. But as the journey progressed she found herself being distracted from the scenery.

The carriage was full of young military officers returning to the capital in high spirits. She thought them annoying at first, but soon caught herself smiling at their banter, along with the other passengers. The officers invited everyone in the carriage to join them in playing games – word games and dice games – to pass the time. When the young woman lost a round, she was told that her forfeit was to sing a song.

The carriage fell quiet. She looked down at the floor, gathered her courage, and stood up, keeping herself steady by holding on to the luggage rack. She was twenty-two years old. Her shiny black hair was pinned back for the journey. She wore a white cotton frock printed with small red flowers. The song she sang was from a popular North Korean movie of that year called The Story of a General. She sang it well, with sweet, high notes. When she finished, everyone in the carriage broke into a round of applause.

She sat back down. A grandmother was sitting on the outside seat and her granddaughter sat between them. Suddenly a young officer in a grey-blue uniform was standing over them. He introduced himself with great courtesy to the grandmother. Then he picked up the little girl, took the seat next to the young woman, and sat the little girl on his lap.

‘Tell me your name,’ was the first thing he said.

This was how my mother met my father.

He sounded very sure of himself. And he spoke with a Pyongyang lilt that made my mother feel uncouth and coarse with her northern Hyesan accent. But he soon put her at her ease. He was from Hyesan himself, he said, but had spent many years in Pyongyang and was ashamed to admit to her that he had lost his accent. She kept her eyes lowered but would steal quick glances at him. He wasn’t handsome in the conventional way – he had thick eyebrows and strong, prominent cheekbones – but she was rather taken with his martial bearing and his self-assurance.

He said he thought her frock was pretty and she gave a shy smile. She liked to dress well because she thought this made up for plain and ordinary looks. In fact she was prettier than she knew. The long journey passed quickly. As they talked she noticed him repeatedly look at her with an earnestness she had not experienced before from a man. It made her face feel hot and flushed.

He asked her how old she was. Then he said, very formally: ‘Would it be acceptable to you if I were to write you a letter?’

She said that it would, and gave him her address.

Later my mother was to recall little of the visit to her brother in Pyongyang. Her mind was filled with images of the officer on the train, and the dappled light in the carriage, of sun shining through mountain pines.

No letter came. As the weeks went by my mother tried to put him out of her mind. He had a girlfriend in Pyongyang, she thought. After three months she’d got over the disappointment and had given up thinking about him.

On an evening six months later, the family was at home in Hyesan. It was well below freezing but the skies had been clear for weeks, making a beautiful autumn and winter. They were finishing dinner when they heard the clip of steel-capped boots approaching the house, and a firm knock on the door. A look of alarm passed around the table. They were not expecting anyone so late. One of my mother’s sisters went to open the door. She called back to my mother.

‘A visitor. For you.’

The power in the city had gone off. My mother went to the door holding a candle. My father was standing on the doorstep, in a military greatcoat, with his cap tucked under his arm. He was shivering. He bowed to her, and apologized, saying that he had been away on military exercises and had not been permitted to write. His smile was tender and even a little nervous. Behind him the stars reached down to the mountains.

She invited him into the warmth. They began courting from that evening.

The next twelve months were dreamlike for my mother. She had never been in love before. My father was still based near Pyongyang, so they wrote letters to each other every week and arranged meetings. My mother visited his military base, and he took the train to see her in Hyesan, where her family got to know him. For her, the weeks between their encounters were filled with the sweetest planning and daydreaming.

She told me once that everything during that time acquired a kind of lustre and magic. People around her seemed to share her optimism, and she may not have been imagining it. The world was at the height of the Cold War, but North Korea was enjoying its best years. Bumper harvests several years in a row meant that food was plentiful. The country’s industries were modern by the standards of the communist world. South Korea, our mortal enemy, was in political chaos, and the hated Yankees had just lost a bruising war against communist forces in Vietnam. The capitalist world seemed to be in decline. There was a confidence throughout the country that history was on our side.

When spring came and the snow on the mountains began to recede my father made a trip to Hyesan to ask my mother to marry him. She accepted with tears. Her happiness was complete. And to cap it all, both his family and hers had good songbun, which made their position in society secure.

Songbun is a caste system that operates in North Korea. A family is classified as loyal, wavering or hostile, depending on what the father’s family was doing at the time just before, during and after the founding of the state in 1948. If your grandfather was descended from workers and peasants, and fought on the right side in the Korean War, your family would be classified as loyal. If, however, your ancestors included landlords, or officials who worked for the Japanese during the colonial occupation, or anyone who had fled to South Korea during the Korean War, your family would be categorized as hostile. Within the three broad categories there are fifty-one gradations of status, ranging from the ruling Kim family at the top, to political prisoners with no hope of release at the bottom. The irony was that the new communist state had created a social hierarchy more elaborate and stratified than anything seen in the time of the feudal emperors. People in the hostile class, which made up about 40 per cent of the population, learned not to dream. They got assigned to farms and mines and manual labour. People in the wavering class might become minor officials, teachers, or hold military ranks removed from the centres of power. Only the loyal class got to live in Pyongyang, had the opportunity to join the Workers’ Party, and had freedom to choose a career. No one was ever told their precise ranking in the songbun system, and yet I think most people knew by intuition, in the same way that in a flock of fifty-one sheep every individual will know precisely which sheep ranks above it and below it in the pecking order. The insidious beauty of it was that it was very easy to sink, but almost impossible to rise in the system, even through marriage, except by some special indulgence of the Great Leader himself. The elite, about 10 or 15 per cent of the population, had to be careful never to make mistakes.