скачать книгу бесплатно

‘I don’t look at the pictures. I buy it for the stories and articles.’

I laughed. ‘Yeah, right.’

His irritation slipped for a second or two to reveal a brief smile. He smiled so rarely these days which was such a shame because when he did it made his eyes sparkle and he looked even more handsome. His eyes were definitely one of his best features. They were hazel, and the exact same shade as his hair. Colour-coordinated, according to Mum. But they were nearly always dulled by sadness. Laughter replaced by melancholy. His spirit sucked out, leaving just the pretty packaging. Dad dying was bad enough, but then the mine closed and took his job and in the months since then he hadn’t been able to find work. The guilt bore down on him. Dad had been big on work and responsibility, believed with passion that everybody should pay their own way in the world.

Graft, he called it.

Graft. That’s all I expect. You can’t hold your head up if you’re not willing to graft.

Mum had tried to hide her fear when Jago told her the mine was done for. White faced, she’d sat at the table and leafed through the red-topped bills to work out which ones needed paying soonest.

It’ll be okay, love. You’ll get another job soon. I know you will.

Wracked by the weight of responsibility, his face had fallen. I’d seen that look on him before. The day after our father died. I’d walked into the kitchen and found him huddled on the floor with his arms clutched around his legs and his cheeks stained with dirty tear-tracks. I was ten, mad with hunger, and even though I’d knocked and knocked, Mum hadn’t come out of her room. I told him I was starving but he didn’t reply. He didn’t even move, not a muscle, and it scared me. It was as if he and Mum had stopped working. As if their batteries had run out.

Jago?

I knelt down next to him and put my hand on his knee.

Jago? Can you hear me? It’s like rats gnawing my belly up.

Maybe it was because I used Dad’s words – what he used to say to us when we were starving hungry – because Jago seemed to click back on. He turned to look at me and I could see his brain whirring behind his eyes. Then he gave a purposeful nod and stood. I sat on the floor, stomach rumbling, and watched him silently walk to the cupboard and get out a pan. Then he took a wooden spoon from the drawer and three eggs from the rack, and set about scrambling them, cracking each into a mug and whisking them with the fork. After he’d heated the eggs on the gas he tipped them onto a slice of toast on a plate and put the plate on the table with a fork beside it. Then he walked back to me, reached for my hand and led me to the table. I stared at the eggs. Two tiny bits of shell decorated the top.

He noticed me looking and picked them out with his fingers.

Eat up, Tam.

The eggs weren’t bad, but I couldn’t take more than a mouthful. I think my tummy was hurting because of crying not hunger, because the food was too hard to swallow and got stuck in my throat like lumps of rock. Jago squeezed my hand and we both sat and stared at the cold egg.

I’m the dad now, aren’t I?

His whispered voice had cracked the silence in two.

I often look back and wish I’d told him, No, of course not, you’re a child who’s lost his father. But I didn’t. I was frightened and sad and missed my dad so much I could hardly breathe. Right at that moment, having Jago as my dad was a better prospect than having no dad at all. So I looked at him and nodded solemnly.

Yes, you are. You’re the dad now.

Jago and I heard the front door open then close, and then Mum call up to tell us she was home.

‘Right, I’ll see you later, half-pint. If she asks just say I’m doing a shift at the yard, okay?’ He grabbed his jacket and pouch of tobacco from the chest of drawers.

‘When are you going to tell her?’

‘Tell her what?’

‘That you don’t actually have a job at the yard.’

He stopped dead, defences up as if I’d flicked a switch. He glared at me. ‘You serious?’

‘You shouldn’t lie to her.’

‘I’m not lying to her.’

I raised my eyebrows.

‘I’m giving her money, aren’t I? She doesn’t need to know where it comes from.’

I didn’t reply, hoping my silence would convey my disapproval.

‘Jesus, Tam. What? You’re the honesty police all of a sudden?’ He gave me a look. ‘I know you lie too, so don’t get all high and mighty.’

I had a flash of the key with the green tag which I’d slipped back into the tin and the rainbow dress that hung in her wardrobe, still damp from my swim, so I relented, nodding, and said,‘Sure, if she asks me, I’ll tell her.’

Mum’s footfalls sounded on the stairs and he swore under his breath. The door opened and he moved to go past her with muttered words I couldn’t decipher.

She stepped in front of him. ‘Can I have a quick chat?’

‘I’m late.’

‘Jago—’

But he was gone, feet hammering down the stairs, ears closed to her. The front door slammed and the walls around us shuddered.

‘Don’t slam the door!’ she shouted. Then she turned to me and forced a light smile. ‘What’s he late for?’ Mum was trying her hardest to sound casual and disinterested.

‘The yard.’ I fixed my eyes on the floor.

‘Again? That’s good. Maybe Rick’ll offer him something full-time.’

I nodded, knotting my fingers into the duvet on his bed, then glanced up at her. She stared at me for a moment or two, waiting, I think, for more information, but then she took a weary breath and gave a quick nod.

‘Cup of tea?’ she asked as she scooped up an empty mug and a sausage roll wrapper from his chest of drawers.

‘That would be nice.’ I was relieved we were safely off the subject of Jago and Rick. Tea was safe. ‘I said I’d get Granfer one, but I haven’t made it yet.’

I followed her out of his room but as we reached the stairs she glanced back at me briefly with a sudden air of awkwardness. ‘Gareth dropped me home. He’s come in for a cup too.’

My stomach leapt up my throat and I stopped dead. ‘But why?’

‘It seemed rude not to ask him in.’ Her eyes flickered from side to side avoiding mine as her lips twitched with obvious discomfort.

I suppose I shouldn’t have been so shocked. Gareth had spent years trying to wheedle his way into our house and he’d clearly succeeded in wearing her down.

‘Oh, love, no need to look like that. It’s not for long.’

‘You know, I don’t want the tea now. I fancy a walk. Will you put two sugars in Granfer’s tea?’ Emotion sprung up and choked my words so I had to fight to stop from crying. ‘I know you don’t like him having more than one, but I promised. And he… he had a pretty bad turn earlier so—’

‘Tamsyn—’

‘It’s fine. I need some air, that’s all.’ I tried to move past her but she grabbed my arm. We looked at each other, neither of us said anything for a moment or two, until finally her eyebrows knotted and she forced a weak smile.

‘It’s just a cup of tea,’ she said softly.

Biting back tears, I eased my arm out of her grip, and ran down the stairs. As I passed the kitchen, I caught the shape of him out of the corner of my eye, and bolted my gaze to the floor as I grabbed my bag off the hook.

‘Tamsyn!’ Mum called.

As soon as I was safely out of sight of the house, I leant back against the wall and kicked it a couple of times with my heel.

It’s just a cup of tea.

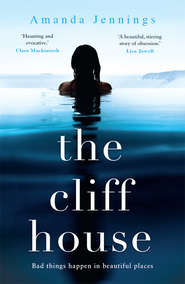

Irritation needled through me. I’d been so excited coming back from The Cliff House and now all I felt was angry. Gareth bloody Spence in our bloody kitchen having a-bloody-nother cup of tea.

I pushed myself off the wall and walked back to the corner of our road. Our front door was closed with no sign of Mum looking for me and Gareth’s crappy car was still parked outside. They were probably sitting at the kitchen table having a good old laugh about teenagers and hormones and slamming doors.

‘Get out of our house, Gareth bloody Spence,’ I whispered through gritted teeth.

I wasn’t going to go back. Not while he was there. No, I was going back to The Cliff House.

The car park was now filled with vehicles parked in obedient rows. I made sure to keep my eyes on the floor as I passed people. I had neither the time nor desire to exchange pleasantries with idiot visitors whose only concern was whether they’d prefer a pub lunch or pasties on the beach.

Relief flooded me the moment I pressed the binoculars against my face. Gareth bloody Spence was gone and she was there, Eleanor, on the terrace of The Cliff House.

‘Hello,’ I whispered. ‘I met your daughter this morning. Isn’t she beautiful? Just like you.’

Eleanor was lying on her sun lounger with a glass beside her and a glossy magazine in her hand. I twisted the dial to make her bigger, then refocused on her outstretched legs, which were scattered with beads of water like glitter. Her scarf was wrapped around her body and I felt the phantom touch of the silk against my skin. I imagined lying beside her, my leg bent like hers, my toe stroking the lacquered surface of the pool.

A movement over by the house caught my attention. It was him. Max Davenport. My stomach knotted as I watched him stroll over to her. He wore a pink collared shirt, beige shorts, and his blue shoes, and he carried a newspaper tucked under one arm. He stood above her, speaking words I couldn’t hear. She tilted her head to look at him, raised her sunglasses on top of her head.

‘You look comfortable, darling,’ I said under my breath. ‘Oh, I am, darling. Isn’t it bliss? Would you like me to fetch you anything? No, my love, I’m perfectly happy. I do love you so. Oh darling! I love you too. Who in the world could be happier than us?’

Eleanor Davenport lowered her sunglasses and returned to her magazine and he crossed the terrace to sit at the table where he shook open his newspaper.

Then I remembered Edie.

I lifted my sights to the windows on the first floor. Scanned them from left to right. Which was hers? I knew the one with the largest window on the far left was her parents’, but which of the other three rooms was Edie’s?

I moved the binoculars across and inhaled sharply. She was there. Standing at the window two along from theirs. Her palm rested against the glass. Was she looking at me? I dropped the binoculars as if the metal was molten and threw myself forward to flatten my body against the grass. I held my breath and, keeping myself hidden, I slowly lifted my head and raised the binoculars up again. I parted the grasses and manoeuvred so I could see through the vegetation for a better view of her window. I focused on her face. I exhaled. She wasn’t looking at me. She was looking down at her parents on the terrace below. Her gaze fixed. Face blank. As I watched she turned away from the window and slipped backwards into the shadows behind her.

I rolled onto my back and stared up at the sky. White clouds raced across the blue. I rested the binoculars on my stomach and coiled my fingers into the grass. I closed my eyes and the sun danced in patterns on my eyelids as I listened to the seagulls and insects scurrying in amongst the heat-dried grasses. I conjured Edie and allowed my mind to drift into daydream. I pictured her back at the window and instead of slipping into the darkness she caught sight of me and waved. Then she opened the window and leant out to call my name. My chest swelled with joy as I waved back at her. Then she beckoned to me. I heard myself laughing as I skipped down the grassy slope and ran along the path to the gate. I threw it open and strode up the lawn. Edie burst out of the house and ran down to greet me whilst Mr and Mrs Davenport stood arm in arm, her with the silk scarf wrapped around her, him in his soft blue leather shoes. They were telling me to hurry up. Telling me how pleased they were to see me. Then in the background I saw my father. He was sitting at the table on the terrace. He held a cigarette in his long slim fingers, a ghostly trail of smoke wending its way upwards, the sun draping him, lighting him up like an angel.

He smiled at me and, as I approached, he nodded his approval.

CHAPTER EIGHT (#ulink_674bbbb6-c8e1-5b90-be05-df11f7c0892a)

Tamsyn

July 1986

All I could think about was going back to The Cliff House to see Edie again. Reasons to go tumbled over and over in my mind as I lay in bed and stared at the cracks that fractured the ceiling.

Perhaps I could tell her the green-tagged key had fallen out of my pocket and my mother was furious and had ordered me to retrace my steps? Or I could tell her I’d lost a ring, or a bracelet, or a pair of socks. Maybe I could offer to show her around? Be her guide. Take her to Porthcurno and the Minack, to St Ives and Logan’s Rock, to Land’s End, or to Penzance to buy paper bags of penny sweets and watch the helicopters take off on their way to the Scilly Isles. I imagined walking her around St Just, our postcard-pretty town. Imagined my patter: Population four thousand, most westerly settlement in mainland Britain, until recently home to a thriving mining industry…

But even if I found the perfect excuse I still couldn’t go. It was Friday morning and on Friday mornings Mum cleaned at The Cliff House in preparation for their possible arrival. Of course, she had no idea they were already there, that they’d arrived early and with a daughter she didn’t know they had.

I lay on my bed and watched her through my open door as she got dressed on the landing. She took her cleaning clothes out of the airing cupboard, her stone-washed denim jeans, white T-shirt, a grey sweatshirt over the top. For work she always tied her hair into a tight ponytail, high enough to be out of her way, and her earrings were simple gold hoops. She didn’t wear any make-up, just some briskly applied Oil of Ulay.

‘You okay?’ she asked with a warm smile as she caught me watching her.

I turned on my side on the pillow and nodded.

‘You look happy snuggled up there,’ she said. ‘I wish I could come and jump in with you. But’ —she sighed— ‘no rest for the char lady.’

I was desperate to share the fact they had a daughter. A girl with white-blonde hair who was called Edie after très glamoureux Edith Piaf. But I stayed quiet. If I told her, she’d ask questions and I might let slip I’d been taking the key and letting myself in, which I knew would send her mental.

She closed the front door and I listened to her footsteps ringing on the pavement until they faded to nothing. My immediate thought was to get out to the rock with my binoculars and watch her in the house with them, but it wasn’t worth the risk. She knew about the spot where Dad used to take me. He’d taken her there too. Even as a boy it had been his favourite place to watch the sun set over the sea and spy on the gulls and kittiwakes and choughs. The chances of her glancing in the direction of the point were significant and if she saw me I’d have to explain why I was there. So I tried to ignore the gnawing lure of the house by keeping myself busy. I cleaned the kitchen, washed-up and dried, changed the sheets on Granfer’s bed then sat with him a while, listening to him attempting to breathe whilst grumbling about the godforsaken government who murdered the tin mines and this being the hardest jigsaw he’d ever tried to do. Then I made him a cup of tea with two and a half sugars in which made him wink and flash me his gap-toothed smile.

When I finally heard the latch click and the front door open, I ran to the top of the stairs, desperate to hear about the house and the Davenports and Edie.

She was hanging her coat on the hook.

‘Hi,’ I said. ‘Good time?’

‘Cleaning?’ She raised her eyebrows and wiped her forehead with her hand. ‘It’s hot today. And I nearly missed the bus and had to run.’ She paused, stared up at me, her brow knotted. ‘The Davenports were there.’

It was then I noticed she held an envelope.

‘What’s that in your hand?’

She looked down as if confused by it. ‘It’s for you.’

‘For me?’

She hesitated. ‘Their daughter asked me to give it to you.’

‘What?’ I squealed and ran down the stairs taking them two at a time and when I got to the bottom I thrust out my hand.

She didn’t give it to me. Instead her hand moved fractionally closer towards her body.

‘Can I have it then?’

She furrowed her brow. ‘I didn’t even know they had—’

But I didn’t let her finish. ‘I can’t believe she wrote to me!’ As I grabbed the letter from her an electric charge shot through me. I stared down at my name which was written across it in the neatest writing I’d ever seen, all the letters even and rounded and perfectly joined up. I beamed at Mum but my smile faded when I saw her expression.

‘How do you know each other?’ she asked with forced indifference.

I gripped the letter hard as my brain turned over and over.