Полная версия:

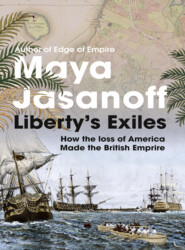

Liberty’s Exiles: The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire.

MAYA JASANOFF

Liberty’s Exiles

The Loss of America and the Remaking of the British Empire

Dedication

In memory of Kamala Sen (1914–2005) and

Edith Jasanoff (1913–2007),

emigrants and storytellers

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

List of Maps

Cast of Characters

Introduction: The Spirit of 1783

PART I: REFUGEES

Chapter One - Civil War

Chapter Two - An Unsettling Peace

Chapter Three - A New World Disorder

PART II: SETTLERS

Chapter Four - The Heart of Empire

Chapter Five - A World in the Wilderness

Chapter Six - Loyal Americas

PART III: SUBJECTS

Chapter Seven - Islands in a Storm

Chapter Eight - False Refuge

Chapter Nine - Promised Land

Chapter Ten - Empires of Liberty

Conclusion: Losers and Founders

Picture Section

Appendix: Measuring the Exodus

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

A Note About the Author

A Note on the Type

Also by Maya Jasanoff

Illustrations Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Notes

List of Maps

The Loyalist Diaspora

The Loyalists’ North America

The Thirteen Colonies in 1776

The Battle of Yorktown

The Southern Colonies During the War

North America After the Peace of Paris

The British Isles

The Maritimes After the Loyalist Influx

Port Roseway, Nova Scotia

Loyalist Settlements on the Saint John River

The Bahamas and the Coast of East Florida

Jamaica

Freetown and the Mouth of the Sierra Leone River

North America in the War of 1812

Northern India

Cast of Characters

(in order of appearance)

BEVERLEY ROBINSON AND FAMILY

A native Virginian, Beverley Robinson (1722–1792) moved to New York and married the wealthy heiress Susanna Philipse in 1748. He raised the Loyal American Regiment in 1777. After the evacuation of New York, Robinson settled in England, where he died in 1792. His widow and two daughters, Susan and Joanna, remained in England until their deaths. His five sons enjoyed profitable careers in different parts of the British Empire. The eldest, beverley robinson jr. (1754–1816), lieutenant colonel of the Loyal American Regiment, settled outside Fredericton in 1787 and became a member of the New Brunswick provincial elite. frederick philipse “phil” robinson (1763–1852) was a career soldier who attained considerable prominence as a general in the Peninsular War and War of 1812, for which services he earned a knighthood. At the time of his death, General Robinson was the “grandfather” of the British army, the longest-serving officer on its books. The youngest son, WILLIAM HENRY ROBINSON (1765–1836), distinguished himself in the British army’s commissariat department, for which he also received a knighthood. He married Catherine Skinner, daughter of loyalist general Cortlandt Skinner, and sister of Maria Skinner Nugent.

JOSEPH BRANT (THAYENDANEGEA) (1743–1807)

As a teenager in colonial New York, the Mohawk Indian Joseph Brant—or Thayendanegea in Mohawk—fell under the patronage of British superintendent of Indian affairs Sir William Johnson, who had married Brant’s elder sister molly (ca. 1736–1796). Brant was educated at Wheelock’s Indian school in Connecticut, and fought for the British in both the Seven Years’ War and Pontiac’s War. During the American Revolution, Joseph and Molly Brant helped recruit Iroquois to the British cause. In 1783 Brant initiated the resettlement of dislocated Mohawks in Canada. From his new home on the Grand River (today’s Brantford, Ontario), Brant tried to reunite Iroquois nations divided by the Canadian-U.S. border, and to establish a new Indian confederacy reaching to the west. He visited Britain twice, in 1775 and 1785, to advance Mohawk land claims; but as the 1790s wore on he found himself increasingly at odds with British colonial officials and saw his hopes for a western confederacy dashed. He died in 1807 and is buried next to the Mohawk Chapel in Brantford.

ELIZABETH LICHTENSTEIN JOHNSTON (1764–1848)

Elizabeth Johnston spent almost half her life on the move. An only child, she lost her mother at the age of ten and spent the early years of the revolution in seclusion while her father, John Lichtenstein, fought in a loyalist regiment. In 1779, she married william martin johnston (1754–1807), a loyalist army captain, medical student, and son of prominent Georgia loyalist Dr. Lewis Johnston. Johnston evacuated with the British from Savannah, Charleston, and East Florida, settling in 1784 in Edinburgh. In 1786 the Johnstons moved to Jamaica, where William worked as a doctor. The years in Jamaica were trying ones for Johnston; she went back to Edinburgh from 1796 to 1802, and in 1806 relocated to Nova Scotia (returning to Jamaica from 1807 to 1810 to wrap up business following William’s death in 1807). She spent her last four decades far more rooted than her first, surrounded by her adult children and her father, who died in Annapolis Royal in 1813. Six of Johnston’s ten children predeceased her, including her eldest son Andrew, of yellow fever in Jamaica in 1805, and her eldest daughter Catherine, in a Boston madhouse in 1819.

DAVID GEORGE (ca. 1743–1810)

David George was born a slave in Virginia. He ran away from his master in 1762, eventually ending up in the custody of Indian trader George Galphin at Silver Bluff, South Carolina. There, partly under the influence of George Liele, George converted to the Baptist faith and became an elder of the Silver Bluff Baptist Church. In 1778, George followed British forces to Savannah, where he worked as a butcher and continued to preach with Liele. With the British evacuations, George and his family traveled to Nova Scotia as free black loyalists. There George became an active evangelist, establishing a church at Shelburne and preaching to white and black audiences around the Maritimes. In 1791 George emerged as a leading supporter of the Sierra Leone Company’s project to relocate black loyalists to Africa, and helped John Clarkson recruit colonists for the scheme. He was among the founding settlers of Freetown in 1792. George visited England in 1792–93, but otherwise spent the rest of his life in Sierra Leone, where he set up another Baptist church (the first in Africa) and died in 1810.

JOHN MURRAY, FOURTH EARL OF DUNMORE (1732–1809)

Dunmore was a Scottish peer whose father supported the Young Pretender in 1745. Despite their Jacobite sympathies, the family retained their title, and Dunmore served for nearly thirty years as a representative peer for Scotland in the House of Lords. He went to North America in 1770 as governor of New York, and became governor of Virginia in 1771. He achieved considerable notoriety for his proclamation of 1775, which granted freedom to patriot-owned slaves who joined British military service. Dunmore became a notable advocate of loyalist interests, promoting numerous schemes to continue the war (including those of John Cruden), and championing loyalist efforts to win financial compensation. He was appointed governor of the Bahamas in 1786, in which capacity he supported William Augustus Bowles’s bids to establish the state of Muskogee. Dunmore was recalled from the governorship in 1796 and remained in Britain until his death.

GUY CARLETON, FIRST BARON DORCHESTER (1724–1808)

A career soldier, the Anglo-Irish Carleton joined the army in 1742 and assisted in the 1759 capture of Quebec, a place he would remain involved with for almost forty years. Carleton served as governor of Quebec from 1766 to 1778, and is best known for his role in authoring the 1774 Quebec Act. Loyalists knew Carleton best, however, in his position as commander in chief of British forces from 1782 to 1783, in which capacity he superintended the evacuations of British-held cities and helped organize the loyalist exodus. Carleton returned to Quebec as governor in chief of British North America in 1786 (and newly ennobled as Lord Dorchester). Though beloved by loyalists, Dorchester found himself at odds with developments in British imperial policy enshrined in the 1791 Canada Act. As at other points in his career, Dorchester clashed repeatedly with his colleagues, and resigned his position in chagrin in 1794. He retired to England in 1796 and lived in comfort as a country squire. His younger brother thomas carleton (ca. 1735–1817) was governor of New Brunswick from 1784 to 1817, though from 1803 until his death he governed in absentia from England.

GEORGE LIELE (ca. 1750–1820)

Liele grew up in Georgia as a slave. He was baptized in 1772 and became an itinerant Baptist preacher, serving as a spiritual mentor to David George. Liele was granted freedom by his loyalist master and spent much of the war in British-occupied Savannah. He there baptized Andrew Bryan, who went on to found the First African Baptist Church in Savannah. On the evacuation of Savannah in 1782, Liele traveled to Jamaica as an indentured servant to loyalist planter Moses Kirkland. He established the island’s first Baptist church in Kingston, but during the 1790s became the subject of increasing persecution for his religious activities. After a charge of sedition failed to stick, Liele was imprisoned for three years for debt. Though he continued to be active in a range of commercial ventures, he never returned to public preaching after 1800, and his last years remain obscure.

JOHN CRUDEN (1754–1787)

Cruden emigrated from Scotland to Wilmington, North Carolina, sometime before 1770, where he joined his uncle (and namesake) in the trading firm of John Cruden and Company. During the war, Cruden served in a loyalist regiment and was appointed commissioner of sequestered estates in Charleston in 1780, which required him to manage numerous patriot-owned plantations and a labor force of several thousand slaves to produce supplies for the British military and for commercial sale. After Charleston was evacuated Cruden moved to East Florida, where he attempted to block the province’s cession to Spain. In 1785, like many East Florida refugees, Cruden immigrated to the Bahamas, where he lived with his uncle on the island of Exuma. He continued to promote plans for the renewal of the British American empire. Cruden died, insane, in the Bahamas in 1787.

WILLIAM AUGUSTUS BOWLES (1763–1805)

Bowles was the most flamboyant loyalist adventurer of his period. He joined a loyalist regiment in 1777 but deserted in 1779 to settle with the Creek Indians. He married the daughter of a Creek chief and spent several years living in her village. After the revolution, Bowles began plotting to unseat political and commercial rivals in Creek country (which had become part of Spanish Florida). He was supported in these aims by Lord Dunmore and various other imperial officials. A first foray into Florida in 1788 ended in fiasco. A second, more ambitious expedition in 1791 brought Bowles closer to his dream of founding a pro-British Creek state, called Muskogee—but he was captured by the Spanish in 1792 and imprisoned in Havana, Cádiz, and the Philippines in turn. In 1798 Bowles escaped, via Sierra Leone, and returned to Florida for a final effort to establish Muskogee. Though this was the most successful bid of all—he built a capital in 1800 near present-day Tallahassee and presided over his domain for several years—he was betrayed in 1803 by Creeks under U.S. influence. He died in Havana, a Spanish prisoner, in 1805.

SUPPORTING FIGURES

Thirteen Colonies

Thomas Brown, loyalist commander, superintendent of Indian affairs.

Joseph Galloway, advocate of imperial union and loyalist lobbyist.

Charles Inglis, clergyman, loyalist pamphleteer, later bishop of Nova Scotia.

William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin, former governor of Pennsylvania, loyalist organizer.

William Smith, chief justice of New York and later Quebec, confidant of Sir Guy Carleton.

Patrick Tonyn, governor of East Florida, 1774–85.

Britain

Samuel Shoemaker, Pennsylvania refugee and friend of painter Benjamin West.

John Eardley Wilmot, MP and loyalist claims commissioner.

Isaac Low, former New York congressman and merchant.

Granville Sharp, abolitionist and sponsor of Sierra Leone settlement.

Nova Scotia

Jacob Bailey, clergyman and author.

John Parr, governor of Nova Scotia, 1782–91.

Benjamin Marston, surveyor of Shelburne.

Boston King, black loyalist carpenter.

“Daddy” Moses Wilkinson, black Methodist preacher.

New Brunswick and Quebec

Edward Winslow, lobbyist for creation of New Brunswick.

Frederick Haldimand, governor of Quebec, 1777–85.

John Graves Simcoe, governor of Upper Canada, 1791–98.

The Bahamas

John Maxwell, governor of the Bahamas, 1780–85 (active).

John Wells, printer and critic of government.

William Wylly, solicitor-general and opponent of Lord Dunmore.

Jamaica

Louisa Wells Aikman, member of loyalist printer family.

Maria Skinner Nugent, diarist, governor’s wife.

Sierra Leone

Thomas Peters, Black Pioneer veteran, leader of resettlement project.

John Clarkson, organizer of loyalist migration, superintendent of Freetown, 1791–92.

Zacharay Macaulay, governor of Sierra Leone, 1794–99.

India

David Ochterlony, East India Company general, conqueror of Nepal.

William Linnaeus Gardner, military adventurer.

Introduction

The Spirit of 1783

THERE WERE TWO SIDES in the American Revolution—but only one was on display early in the afternoon of November 25, 1783, when General George Washington rode on a grey horse into New York City. By his side trotted the governor of New York, flanked by an escort of mounted guards. Portly general Henry Knox followed close behind, leading officers of the Continental Army eight abreast down the Bowery. Long lines of civilians trailed after them, some on horseback, others on foot, wearing black-and-white cockades and sprigs of laurel in their hats.1 Hundreds crammed into the streets to watch as the choreographed procession made its way down to the Battery, at Manhattan’s southern tip. Since 1776, through seven long years of war and peace negotiations, New York had been occupied by the British army. Today, the British were going. A cannon shot at 1 p.m. sounded the departure of the last British troops from their posts. They marched to the docks, clambered into longboats, and rowed out to the transports waiting in the harbor. The British occupation of the United States was officially over.2

George Washington’s triumphal entrance into New York City was the closest thing the winners of the American Revolution ever had to a victory parade. For a week, patriots celebrated the evacuation with feasts, bonfires, illuminations, and the biggest fireworks display ever staged in North America.3 At Fraunces’s Tavern, Washington and his friends drank rounds of toasts late into the night. To the United States of America! To America’s European allies, France and Spain! To the American “Heroes, who have fallen for our Freedom”! “May America be an Assylum to the persecuted of the Earth!”4 A few days later one newspaper printed an anecdote about a brief shore visit made by a British officer. Convinced that New York would be racked by unrest following the transfer of power, the officer was surprised to find “that every thing in the city was civil and tranquil, no mobs—no riots—no disorders.” “These Americans,” he marveled, “are a curious original people, they know how to govern themselves, but nobody else can govern them.”5 Generations of New Yorkers commemorated November 25 as “Evacuation Day”—an anniversary that was later folded into the more enduring November celebration of American national togetherness, Thanksgiving Day.6

But what if you hadn’t wanted the British to leave? Mixed in among the happy New York crowd that day were other, less cheerful faces.7 For loyalists—colonists who had sided with Britain during the war—the departure of the British troops spelled worry, not jubilation. During the war, tens of thousands of loyalists had moved for safety into New York and other British-held cities. The British withdrawal raised urgent questions about their future. What kind of treatment could they expect in the new United States? Would they be jailed? Would they be attacked? Would they retain their property, or hold on to their jobs? Confronting real doubts about their lives, liberty, and potential happiness in the United States, sixty thousand loyalists decided to follow the British and take their chances elsewhere in the British Empire. They took fifteen thousand black slaves with them, bringing the total exodus to seventy-five thousand people—or about one in forty members of the American population.8

They traveled to Canada, they sailed for Britain, they journeyed to the Bahamas and the West Indies; some would venture still farther afield, to Africa and India. But wherever they went, this voyage into exile was a trip into the unknown. In America the refugees left behind friends and relatives, careers and land, houses and native streets—the entire milieu in which they had built their lives. For them, America seemed less “an Assylum to the persecuted” than a potential persecutor. It was the British Empire that would be their asylum, offering land, emergency relief, and financial incentives to help them start over. Evacuation Day did not mark an end for the loyalist refugees. It was a fresh beginning—and it carried them into a dynamic if uncertain new world.

JACOB BAILEY, for one, could give a vivid account of what led him to flee revolutionary America. Massachusetts born and bred, Bailey had since 1760 been an Anglican missionary in the frontier district of Pownalborough, Maine. While he ministered in what was then remote wilderness, in Boston his Harvard classmate John Adams voiced the colonies’ grievances against Britain, and became a forceful advocate for independence. But Bailey had sworn what he regarded as a sacred oath to the king, the head of his church, and to renounce that allegiance appeared to him to be an act of both treason and sacrilege. Bailey struggled to maintain his loyalty in the face of mounting pressure to join the rebellion. When he refused to honor a special day of thanksgiving declared by the provincial congress, Pownalborough patriots threatened to put up a liberty pole in front of the church and to whip him there if he failed to bless it.9 Another frightening omen came when he found seven of his sheep slaughtered, and a “fine heifer” shot dead in his pasture.10 By 1778, the clergyman had been “twice assaulted by a furious Mob—four times haulled before an unfeeling committee. . . . Three times have I been driven from my family....Two attempts have been made to shoot me.” He roved the countryside to elude arrest, while his young wife and their children tried to get by with “nothing to eat for several days together.” To Bailey the patriots were persecutors, plain and simple, a “set of surly & savage beings who have power in their hands and murder in their hearts, who thirst, and pant, and roar for the blood of those who have any connection with, or affection for Great Britain.”11

Bailey certainly had a flair for sensational language. His melodramatic prose, however, spoke to genuine fear for his family’s safety. Still unwilling to renounce the king—yet equally unwilling to risk imprisonment for refusing to do so—he saw only one more option before him, unappealing though it was. Before dawn one June day in 1779, the Baileys grimly “began to prepare for our expulsion.” They dressed in a motley assortment of salvaged clothes, gathered up their bedding and “the shattered remains of our fortune,” and made their way to a boat that would carry them to Nova Scotia, the nearest British sanctuary. In spite of all they had suffered, Jacob and Sally Bailey could not hold back their “bitter emotions of grief ” on leaving their native country. Neither could they contain their relief, two weeks later, when they sailed into Halifax harbor and saw “the Britanic colours flying.”12 Bailey gave thanks to God “for safely conducting me and my family to this retreat of freedom and security from the rage of tyranny and the cruelty of opposition.” Now they were in the British Empire; now they were secure. But the Baileys had landed “in a strange country, destitute of money, clothing, dwelling or furniture,” and their future was in the hands of chance.13

This book follows refugees like Jacob Bailey out of revolutionary America to provide the first global history of the loyalist diaspora. Though historians have probed the experiences of loyalists within the colonies (and especially the ideology of articulate figures like Bailey), the international displacement of loyalists during and after the war has never been described in full.14 Who were these refugees and why did they leave? The answers came in as many forms as the people themselves. Loyalists are often stereotyped as members of a small conservative elite: rich, educated, Anglican, and with strong ties to Britain—qualities captured by the pejorative label “tory,” the nickname for the British Conservative Party.15 In fact, historians estimate that between a fifth and a third of American colonists remained loyal to the king.16 Loyalism cut right across the social, geographical, racial, and ethnic spectrum of early America—making loyalists every bit as “American” as their patriot fellow subjects. Loyalists included recent immigrants and Mayflower descendants alike. They could be royal officials as well as bakers, carpenters, tailors, and printers. There were Anglican ministers as well as Methodists and Quakers; cosmopolitan Bostonians and backcountry farmers in the Carolinas.

Crucially, not all loyalists were white. For the half million black slaves in the thirteen colonies, the revolution presented a striking opportunity when British officers offered freedom to slaves who agreed to fight. Twenty thousand slaves seized this promise, making the revolution the occasion for the largest emancipation of North American slaves until the U.S. Civil War. For native American Indians, too, the revolution posed a pressing choice. Encroached on by generations of land-hungry colonists, several Indian nations—notably the Mohawks in the north and the Creeks in the south—opted to ally themselves with the British Empire. The experiences of loyal whites, blacks, and Indians have generally been segregated into distinct historical narratives, and of course there were important differences among them.17 But loyalists of all backgrounds confronted a common dilemma with Britain’s defeat—to stay or go—and all numbered among the revolution’s refugees. Their stories were analogous and entangled in significant ways, which is why they will be presented together here.