скачать книгу бесплатно

‘Chapel did you say?’ came a nasal, unenthusiastic voice. ‘Can’t seem to find you anywhere.’

The boy turned and looked across the desk at the school secretary, a large, middle-aged woman with bleached hair, wearing a turquoise blouse that was one size too small for her ample figure.

‘Chapman,’ he said with mild annoyance, exaggerating his lip movements in case the chunky earrings she wore had made her hard of hearing.

The woman dabbed at the computer with her podgy fingers and without looking up at him said, ‘You’re in Mr Battersby’s form. Room 11a, down the corridor on the right.’

‘Thank you,’ Neil muttered, slinging his bag over one shoulder.

‘They won’t be there now though,’ the secretary added. ‘There’s an assembly this morning. They’ll have gone to the drama centre, across the playground on the left. You’d best get a move on – you’re late.’

Neil didn’t bother to answer that one. He hurried from the main doors and into the rain again. Over a bleak tarmac square he ran to where a low building stood, and hastened inside.

Fortunately, the assembly had not yet begun and Neil slipped in amongst the children still finding their seats.

The drama centre was a modestly sized theatre where school plays, concerts and assemblies were held. It consisted of a stage, complete with curtains and lighting equipment, and tiered rows of seats to accommodate the audience.

Today the atmosphere was rowdy and irreverent. The stale smell of damp clothes and wet hair hung heavily in the air as the congregated pupils settled noisily into their places. The watchful teachers patrolled up and down, keeping their expert eyes upon the troublesome ones. Several of these had pushed their way to the back of the highest row but were already being summoned down again to be divided and placed elsewhere under easy scrutiny.

Neil’s eyes roved about the large room. At the back of the stage there was a backdrop left over from the last school production, depicting the interior of an old country house complete with French windows, and he guessed that it had been a murder mystery.

In front of the scenery was a row of chairs which faced the pupils and already some of the teachers had taken their places upon them. There were two female teachers and three male, but against that painted setting they looked less like members of staff and more like a collection of suspects.

Mentally performing his own detective work, Neil wondered which of them was Mr Battersby. Of the three men sitting there, one was fat and balding, another tall and slightly hunched, but the last one Neil dismissed right away for he was obviously some kind of vicar, dressed in long black vestments.

Suddenly, the level of chatter died down as a small, stern looking woman with short dark hair strode into the room. One of the male teachers who had not yet joined his colleagues raised his hand as though he was directing traffic and at once the children in the theatre stood.

Neil did the same. This was the headteacher, Mrs Stride.

‘Good morning,’ she said, briskly rubbing her hands together.

The children mumbled their replies.

‘I said, “good morning”,’ she repeated, a little more forcefully.

This time the response was louder and Mrs Stride appeared satisfied. Nodding her head, she told them to be seated and the room echoed with the shuffling of over three hundred pairs of feet and the usual chorus of pretended coughs before she could begin.

Only half listening, Neil watched the head pace up and down the stage, but his attention was quickly drawn away from her and directed at the person sitting beside him.

Here was a slight, nervous looking boy with untidy hair and large round spectacles, whose threadbare blazer was covered in badges. With one watchful eye upon the teachers, the boy lifted his bag with his foot, unzipped it and drew out a science fiction magazine which he laid upon his lap and proceeded to read, ignoring everything else around him.

Lowering his eyes, Neil peered at the colourful pages and read the bold type announcing ‘real life’ abductions by strange visitors from outer space.

‘Now,’ Mrs Stride’s voice cut into his musings and Neil returned his gaze to the front of the stage. ‘You all know Reverend Galloway. He came to see you quite a few times last term to talk about the youth club, before it burned down. Well, I haven’t a clue what he’s going to tell us this morning but I’m sure it will be most interesting. He’s even gone all out and put his cassock on for us. Reverend Galloway.’

The head stood aside as the man in the vestments rose from his seat and a distinct groan issued about the theatre.

‘Not the God Squad again,’ complained a dejected voice close by, and Neil looked at the boy at his side who had glanced up from his magazine to contribute this mournful and damning plea.

Neil studied the vicar more closely. Apparently he was a familiar and unpopular guest at these assemblies.

The Reverend Peter Galloway was a boisterous young man with a haystack of floppy auburn hair and a sparse, wispy beard to match. Suddenly, he broke into an enormous, welcoming grin and his large, green eyes bulged forward as if they were about to pop clean out of his head. Then he held open his arms in a great sweeping gesture which embraced the whole audience.

‘I hope you all enjoyed Christmas,’ he said benignly.

The children eyed him warily as though he were trying to sell them something and an agitated murmur rippled throughout the tiered seats.

Peter Galloway looked at the sea of blank faces. The pupils’ expressions were those of bored disinterest but that did not deter him, in fact it spurred him on. For the past seven months, ever since he had left college, he had ministered to the spiritual needs of this difficult area and never once suffered any loss of confidence, whatever the reaction to his exuberant ministries. His soul brimmed with the joy of his unshakable beliefs and he never missed an opportunity to try and share this with others.

In this short time, however, the Reverend had become increasingly aware that the Church was failing to capture the hearts and minds of the younger members of the community, and was grieved to learn of the trouble they got themselves into. If they could only channel all that youthful, restless energy into celebrating the life that God had given to them, as he did, they could enjoy a faith as strong as his own.

This mission to welcome the youngsters into the fold had become a crusade with him. He was passionate about it and tried many different ways to show them that the Church could be fun. There had been concerts of Christian pop music, youth groups, debating societies, sporting events and even sponsored fasts in aid of the Third World. Yet none had been a resounding success, in spite of his finest efforts. The teenagers he saw hanging around in gangs and loitering at street corners never came along to any of them, but it only served to make him even more determined.

Today he had resolved to take a more direct approach with the children and he returned their apathetic stares with a knowing glare of his own.

‘Let us not forget,’ he addressed them, ‘that Christmas is not merely a time for exchanging gifts. We must remember its tremendous significance. At that season the Saviour of Mankind was born.’

At the back of the audience a girl began to giggle into her hand. Neil looked across at the teachers and found that they too appeared bored.

‘Can you imagine the wonder that the people felt at the time of the Nativity?’ the Reverend Galloway continued, jabbing his finger in the air. ‘It must have been absolutely incredible for them. Think of the shepherds who fell on their faces in terror when the angel appeared – revealed in glory.’

At Neil’s side the bespectacled boy muttered in a loud whisper which everyone heard, ‘I’d be scared too if a man in a white dress revealed his glory.’

The children burst into fits of laughter and although the teachers looked stern and accusing, several of them could not completely disguise the smirks which had crept on to their faces.

Peter Galloway waited for the mirth to die down, but he gazed in the direction that the mocking voice had come from and nodded in energetic agreement.

‘But that’s precisely my point!’ he exclaimed to everyone’s surprise. ‘If we are to get anywhere, you have to dismiss the silly, archetypal image of an angel. That’s utter, utter rubbish and belongs only on the top of a Christmas tree. A messenger of God isn’t a person dressed up with wings and a halo, with a harp in their hand. That’s an invention by medieval artists who had no idea how to illustrate or express such an amazing, celestial being.’

Lowering his voice slightly, the vicar leaned forward to speak to them in a hushed, conspiratorial voice.

‘Imagine,’ he began, drawing his hand from left to right as if pulling back an obscuring curtain. ‘Picture it in your mind, the stony landscape outside Bethlehem. Upon those barren, exposed hillsides it is dark and cold. To live there takes a certain type of stamina and courage, the people wouldn’t tolerate any sort of nonsense. These shepherds are used to the brutalities and hardships of Roman rule. Only something truly terrifying could possibly frighten them.

‘There they are, encamped about a small fire perhaps, when suddenly their hearts are stricken with a mortal and petrifying dread. The angel of the Lord! Now, we here today haven’t a clue what that really means, but it was a sight so awful that it put the fear of God into those men. What can it have looked like, this monstrous vision? Was it merely a fierce, bright light or did the angel have a more tangible, unhuman form? What is the real shape of a heavenly messenger? Whatever it is, it scares the hell out of ordinary people like you and me.’

At Neil’s side, the boy with the magazine listened intently, before glancing down at the glossy pages where a painting of a grotesque, nightmarish alien roared up at him and he nodded appreciatively. ‘Yeah,’ he murmured.

‘All you have to do is think about it,’ the vicar went on, sensing with mounting excitement that his audience was paying attention.

‘These events really happened, they’re not legends or myths – they are historical facts. This man with the strange, radical ideas actually lived and, when he was only thirty-three, he was executed because he had dared to think them.’

Taking a breath for dramatic effect, the vicar drew himself up and swept the wild mop of auburn hair from his eyes.

‘Do any of you know what it means to be crucified?’ he asked.

The pupils nodded but the Reverend Galloway shook his head. ‘No, you don’t,’ he told them. ‘Oh yes, you’ve seen all the pictures and statues of Him, with His arms outstretched upon the cross, with nails in the palms of His hands and embedded in His feet. That isn’t right – that’s a twee prettification for old ladies to pray to and what we’d like to believe. The truth was far, far worse and bloodier than that.’

‘Cool,’ said Neil’s neighbour, letting the magazine fall to the floor whilst the teachers shifted uncomfortably upon their chairs and Mrs Stride uttered nervous little coughs.

‘No, the nails didn’t go through the hands. The bones aren’t strong enough there – they’d shatter and wouldn’t support the weight of the arms. Through the wrists the nails were hammered and, if you were lucky, it’d sever the arteries and you’d bleed to death. But if you weren’t, then the feet would be skewered to the cross, only they’d be pinned to it either side, with the nails driven through the heels.’

For the first time in over a dozen visits, the vicar knew that the children were listening to him. Some of the more squeamish ones might have been appalled at the gruesome details, whilst others were morbidly fascinated, but all of them were enthralled.

‘When the hammering was over,’ Peter Galloway resumed, ‘the cross was hoisted upright and there you’d stay until you died. Most people probably perished from shock but others suffocated. Hanging there, with your head slumped on your chest, the only way to draw a proper breath would be to push yourself up by the nails impaling your heels. But to stop the prisoners doing this, the Roman guards went round to each one and savagely broke their legs.

‘That is what happened to the man born in Bethlehem – His legs were smashed and splintered, but still He lived. Although the agony and the suffering was excruciating, somehow He managed to cling to life. However, the following day was the Sabbath and no one was permitted to be on the cross during that time. Having survived all this torment and pain, our Lord was finally killed by a Roman spear thrust viciously into His side.’

The headteacher had never known the theatre to be so full and yet so silent. Looking worriedly at the children, she hoped none of them was going to be sick and had already decided to have a word with the Reverend Galloway afterwards. If she ever allowed him to speak to the pupils again she would make certain she knew what he was going to say beforehand.

Taking a step towards him, she hoped to lead the outrageous man from the stage and let the children return to their classes. But the Reverend was not done yet.

‘Yes,’ he cried, revelling in the unfamiliar but immensely gratifying experience of holding their undivided attention. ‘That man died on the cross. He was tortured for the sins of the world, but He rose from the tomb and because of His ultimate sacrifice, we can all find forgiveness and know true happiness.’

Trembling with excitement, the Reverend ran to the edge of the stage where he had placed a tape recorder upon a table, but hesitated before pressing the play button.

‘This is what it’s like to feel that joy,’ he enthused. ‘To know that incredible elation of the soul. The Lord lives in me and in all of you if you’ll let Him. He is knocking upon the door of your heart right now, and don’t turn Him away. He is the light of the world, the Son of Man – “the Lord of the Dance”.’

With that he punched the button down and the tune to that hymn began to blare from the speakers.

In one practised movement, Peter ripped open his cassock to reveal a full length black leotard and at once he began to leap about the stage in time to the music.

Waving his long arms in the air, he capered around in a wide circle, waggling his head from side to side and tapping his feet upon the floor as the hymn played on.

For a whole minute both the children and the members of staff could only gape at the zealous young man as he endeavoured to illustrate the overwhelming joy that so consumed his spirit.

No one could quite believe what they were witnessing. The sight of the Reverend Galloway cavorting about the stage, twisting and gyrating to the music, was the strangest spectacle most of them had ever seen and they were frozen with astonishment.

To and fro he gambolled and the expression on his face was one of perfect serenity. In his mind’s eye he was as graceful as a swan, exquisitely conveying in the poetry of his movements all that he could not form into words. In reality however, in that black leotard and with his wild haystack of hair, he looked more like a member of some bizarre circus launching into a peculiar and ungainly mime. Blissfully unaware of the effect this unexpected performance was having, he danced on – but it did not last for long.

As the tape recorder continued to thump out the tune, gradually the general amazement thawed, and the pupils began to stir and look at one another. Quickly the shock subsided and, in one great united voice, the entire theatre erupted with a terrific peal of laughter.

Totally unprepared for this explosive reaction, when the shrieks and hoots of ridicule came, Peter’s steps faltered and he stared about him – bewildered and dismayed.

‘No,’ he protested. ‘You don’t understand. All I’m trying to do... it’s the beauty of God’s love... please. I just wanted to show how wonderful it makes me feel... can’t you see that? Listen to me. Children, listen.’

But it was no use. The respect he had commanded only a few minutes ago when he appealed to their bloodthirsty natures was gone. There was no way he could reclaim it and, to his horror, he saw that the teachers too were sniggering behind their hands. Staring at them, with the children’s derisive laughter trumpeting in his ears, the colour rose in his face as a bitter coldness gripped the pit of his stomach and he realised the full extent of his humiliation.

Just as the audience had begun to harken to his words and think about what he was trying to communicate to them, he had thrown it all away by his own misjudgement. How could he have been so blind not to consider the preposterous exhibition he was going to make of himself?

His hopes and spirits crushed, the Reverend Galloway walked over to the tape recorder and turned it off. Then, retrieving his cassock, he left the theatre with the laughter still resounding in his ears and branded upon his heart.

‘All right, all right,’ Mrs Stride called. ‘That’s enough, the fun’s over – we’ll have The Lord’s Prayer.’

Still tittering, the children bowed their heads and began to chant. ‘Our Father...’ Murmuring along with them, Neil wondered if the world outside The Wyrd Museum had always been this strange and he just hadn’t noticed before, whilst at his side the bespectacled boy uttered, ‘Dear Alien, up in your spaceship...’

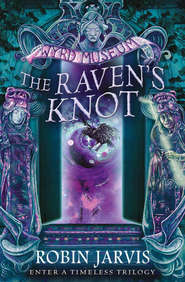

So Neil’s first day at his new school commenced. But when the assembly was over and he trailed off to his first lesson, he found himself longing once more for the excitement of The Wyrd Museum. Already he missed the dark, shadowy corners of its lonely galleries and the display cabinets with their unusual exhibits. Yet as he sat at his desk, the time when the Webster sisters would need his help again was already drawing near.

Ever since her outburst in the Chamber of Nirinel, Miss Veronica had been sullen and silent. Now, sitting in a worn leather armchair, with her cane resting upon her lap, she stared vacantly at the small square window, watching the rain streak down the diamond latticed panes.

Over her white powdered face the faint drizzling shadows fell, but whether she was aware of the soft, rippling light or was lost in a corner of her jumbled mind it was impossible to determine.

A plate of her favourite delicacy, jam and pancakes, lay untouched upon the table at her side and this fact alone worried her sister.

Miss Celandine Webster had tried everything she could think of to coax and cajole Miss Veronica out of her tedious sulk, but the wizened woman in the armchair was oblivious to all her urging.

‘You’re no fun today, Veronica,’ whined Celandine. ‘It’s not fair – it isn’t!’

‘Let her be, Celandine,’ a curt, impatient voice interrupted. ‘If Veronica wishes to be childish do not spoil it for her.’

Miss Celandine turned her nut-brown face to the fireplace where Miss Ursula, resplendent in a black beaded evening gown, stood cold and detached.

‘But it isn’t like her, Ursula!’ she protested. ‘Veronica never mopes, not ever’

‘Then she’s obviously making up for lost time,’ came the cold reply. ‘Leave her alone.’

The Websters’ quarters were a poky little apartment situated at the top of The Wyrd Museum. Cluttered with bric-a-brac collected over the endless years, it was almost a monument to the building’s history.

Images of the place in various stages of its enduring existence covered the shabby wallpaper; from a small stone shrine to a twelfth century manor house. A later watercolour showed the building to be a graceful Queen Anne residence surrounded by well-tended gardens. But the final portrait of the ever expanding abode of the three Fates was a faded, sepia photograph of the stark and severe looking Well Lane Workhouse and this grim print brought the record to a bleak and melancholy close.

Unaffected by the tense, oppressive atmosphere, Edie Dorkins paid little attention to the Websters’ squabbles. She was too busy examining the dust-covered ornaments and fingering the collection of delicate, antique fans to care what the others were doing. For her the place was a treasury of enchantment. She felt so blissfully at ease and welcome that sometimes the rapturous sense of belonging swelled so greatly inside her that she wanted to run outside and hug every corner of the ugly building.

Lifting her gaze to the mantelpiece, Edie looked only briefly at the oval Victorian painting of the three sisters, before staring with fascination at the vases which stood upon either side. Never had she seen anything like the peacock feathers which those vessels contained and she quickly pulled a chair over to the fireplace to scramble up and snatch a handful.

‘Lor’!’ she exclaimed, shaking off the dust and holding the plumes up to the dim light. ‘They’re lovely. Can I keep ’em?’

‘They are yours already, Edith, dear,’ Miss Ursula replied. ‘Everything here is yours, you know that.’

Edie chuckled and gloated over the shimmering blues and greens, like a miser with his gold.

‘I never seen a bird with fevvers like this,’ she muttered. ‘Much nicer’n that big black ’un last night.’

Miss Ursula smiled indulgently. ‘I really must get that fool of a caretaker to board up the broken windows,’ she said. ‘I cannot have the museum overrun with pigeons.’

‘Weren’t no pigeon!’ Edie cried. ‘Were the biggest crow I ever saw. Bold he were too, chased me clean through the rooms downstairs and tried to bite he did.’

Hoisting the hem of her skirt, she pulled and twisted her hole-riddled stockings to show the others the raven’s clawmarks.

‘Make a real good scab that will,’ she grinned. ‘I was gonna get me own back but the mean old bird took off before I could catch him.’

Miss Ursula’s long face had become stern and her elegant eyebrows twitched with irritation.

‘A large crow,’ she repeated in a wavering voice. ‘Are you certain you are not mistaken, Edith?’

The girl fished in the pocket of her coat, pulled out the talon that the creature had left behind and flourished it proudly.

‘There!’ she declared. ‘That don’t come from no mangy pigeon – see!’

Miss Ursula stepped forward, the taffeta of her dress rustling like dry grass as she moved, and took the severed claw between her fingers.