скачать книгу бесплатно

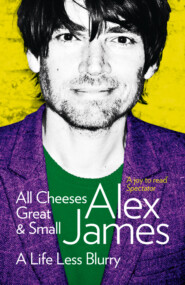

All Cheeses Great and Small: A Life Less Blurry

Alex James

This is the story of Alex James’s transition from a leading light of the Britpop movement in the 1990s, to gentleman farmer, artisan cheese-maker and father of five.All Cheeses Great and Small is the follow-up memoir to Alex James's first book, Bit of a Blur, the story of his excessive pop star lifestyle during the nineties. But now Alex has grown up, fallen in love and got married. He has also fallen passionately for his new home, an enormous rambling farmhouse in the Cotswolds, set in two hundred acres of beautiful British countryside.The farm represents not just a new house for Alex, but also a new career. As he breathes new life into the old farm he chances across an unexpected calling: making cheese. His cheeses, Blue Monday, Farleigh Wallop and Little Wallop have received widespread media interest and are now sold through many outlets.The story culminates with an account of the triumphant reformation of Blur for Glastonbury 2009.

ALEX JAMES

ALL CHEESES GREAT AND SMALL

A LIFE LESS BLURRY

Dedication (#uc0b83f4b-1c23-5fcb-ac69-74ddf2dbeb31)

FOR CLAIRE NEATE JAMES

Contents

Cover (#u2ea34fcf-27ce-53ee-8456-544c581b0a20)

Title Page (#u7dc2528d-6890-59aa-9bf5-2fd88adcfb4d)

Dedication

AUTUMN

Chapter 1 - House with a Hundred Rooms

Chapter 2 - Some People and Animals

Chapter 3 - Britain’s Best Village

WINTER

Chapter 4 - Country Christmas

Chapter 5 - Hot Shots

Chapter 6 - Cheese

SPRING

Chapter 7 - Music

Chapter 8 - Food

Chapter 9 - Love

SUMMER

Chapter 10 - Family and Friends

Chapter 11 - High Days and Holidays

Chapter 12 - Encore

Acknowledgements

Also by Alex James

Copyright

About the Publisher

AUTUMN (#uc0b83f4b-1c23-5fcb-ac69-74ddf2dbeb31)

CHAPTER 1 (#uc0b83f4b-1c23-5fcb-ac69-74ddf2dbeb31)

HOUSE WITH A

HUNDRED ROOMS

The end of the week, the end of summer: it was warm. Traffic crawling and brawling round the outside of Oxford. I stopped for fuel: the stench of petrol and the glare from the concrete apron.

I’d watched the white van stagger to a halt as the driver slammed the brakes on. I’d watched as it began to reverse towards me. There was the moment I knew he was going to hit me, and then I was flying backwards as the van smashed through the front of the old BMW I was sitting in. I’d been reversed into at high speed. Strange. There was another dent to add to the collection on the back of the van and the front of the BMW had completely caved in. Steam was hissing out of the radiator.

I wasn’t hurt, but I was furious that I might have been, and even more furious about the car. I leapt out onto the concrete and began to call the driver names. Many names. There were two of them in the van. They both got out.

‘Prove it,’ said one.

‘You just drove into us,’ said the other.

It was hot and the roads were packed. I had the keys to my new life in my pocket. I bought half a dozen bottles of water from the cashier and stopped every five miles, every three, every one – as often as was necessary to top up the radiator while the temperature gauge hovered around the red. Crawling up the sides of apparently endless valleys. One more hill, one more dale until by fits and spurts I must have been pretty much at the middle of England: the very middle. Here, you might easily think that what is really quite a small island continues forever and ever. I coasted the last mile down the side of the last valley towards my new home. There were gypsies camping on the roadside at the top of the drive oblivious to the car doing ten miles an hour with steam coming out of the radiator. An old lady was doing some washing and was bent over with her backside hanging out of her full skirt.

I knew the car was a write-off. I just needed it to get me home, or what I was about to call home. Because I’d just got married and swapped a London townhouse, with no garden, for a rambling farm. Why would I do that? It seemed straightforward when we were signing the paperwork. I thought that everyone wanted to move to the country and live in a cottage with the roses around the door. What I was doing was blindingly obvious to me, but when I’d started to try and explain it to other people it seemed no one else thought so. I had to answer lots of questions. My friends looked at me long and hard, like I’d started speaking a foreign language.

It wasn’t until about the seventh time that Blur went to Japan that I managed to get out to the countryside there. ‘I’d like to go out into the country,’ I’d say hopefully, every time I arrived in Tokyo as soon as my hangover kicked in. It seemed to me a perfectly simple wish but it didn’t make any sense to my hosts. ‘Where in the countryside exactly?’ they would say, diligently, ‘what you want to do?’ I wanted to go to the middle of nowhere and do absolutely nothing. It was no more complicated than that. And that was what I was doing now, just on a larger scale.

I had always been a man of leisure. I grew up in Bournemouth, a tourist resort, and was at my happiest fiddling about in the New Forest, on beaches, on the sea, in coves and quarries where there was nothing remotely particular to do: just magnificent scenery, a fantastic stage with fantastic lighting. The backdrop of the sea and the open sky that soaks that world right through is an open invitation to relax and play. But it was as if – to the Japanese, a conscientious hardworking people – the idea of just venturing off towards nowhere, going somewhere that is beyond the bump and grind, beyond industry, beyond the workaday, just didn’t really add up. At least, it took some explaining. ‘Well, I don’t really want to do anything: maybe walk around a bit, jump off some cliffs, throw some stones. You know, that kind of thing.’ They’d looked at me strangely then, and they looked at me strangely now.

Around Blur’s fifth Japanese tour I eventually got as far as a little spa town in the mountains, and it was well worth waiting for. Doing things in cities can be hit and miss, but going anywhere in the country is always a safe bet because there is nothing in nature that is not fantastically beautiful. You know what you’re going to get. Even those parts of Iceland that smell a bit eggy are worth having a look at.

Home, since I’d left college, had been Covent Garden. A one-bedroom flat when I was poor, and a house in the next street when the band sold some records. Claire and I fell in love one weekend in the Cotswolds and got married nine months after we met. We bought the farm on our honeymoon, at which point Blur promptly disintegrated. So I arrived in the country with a woman I didn’t really know. Well, kind of with her. She was at work. I, on the other hand, didn’t currently have a job. My friends were disgusted that I’d stopped drinking for a bit to get married, and now I’d appalled them further by walking out on them altogether. People said things like: ‘How can you be a farmer? You don’t know anything about farms?’ or ‘How can you be a husband? You’re an arsehole.’

The main reason for going to the country was to be with her. I didn’t know anybody in the Cotswolds; I didn’t really know anything. Living the quiet life would have driven me utterly mad until I met her. It wasn’t until I wanted to get married that the countryside started to attract me for reasons other than as a hangover cure. I’d spent my entire adult life living in the West End: the most metropolitan part of the largest city in Europe. But I was only there when I wasn’t tearing around other large cities on tour with the band and gradually I’d found that I’d become addicted to big cities, their glamour, drama and possibilities. Now, though, I was definitely ready for a change.

We’d looked at lots of places. When we first saw the farm, there were a lot of fish in tanks in the cellar. In fact it looked like the people might be moving because they needed somewhere with a bigger cellar. The place was chock-a-block with tanks at all angles, and pumps and manifolds gurgling away. The fish were the first thing we were shown when we came to view the place.

‘Are there woods? Where are the woods?’ said Claire. ‘Ah, yes, the woods. I think we’ll just start by having a quick look in the cellar, though,’ said the vendor. The fish weren’t included in the sale. He just wanted us to see them. He took the fish with him, or they took him. He really didn’t want to sell the place, the farmer. Poor man had been a beef specialist: punched on the nose by BSE, then kicked in the face by foot and mouth. He’d spent the last ten years watching everything he’d spent his life building, slip through his fingers as his profits dwindled and his assets corroded. It had been the worst time in history to be a farmer. The place was a ruin, but he’d loved it and poured his life into it. He was crying as he handed over the key, that was in my pocket now.

I cut the dying engine as I pulled off the road and was suddenly aware I was arriving at a point of silence. Silence and stillness. The gentle sounds, the pulses and tunes that had been there all along revealed themselves to my conscious mind. Rabbits scattered as I coasted slowly and gently down the drive in the filthy, dying car, with the front caved in and the rear driver’s side window missing from an earlier incident.

It was rural, properly rural. People had asked me where it was we were going and there was no easy way to describe it. There were no towns nearby – the Industrial Revolution skipped the Cotswolds. It was an area that had never been built up. I didn’t really know where the Cotswolds began or ended, although Oxford was possibly involved and Cheltenham. It was pure English countryside and that means old money and dynastic families wherever you go, but it also had more than its fair share of billionaire tradesmen, and lately, television personalities, film directors and media moguls.

I remember the feeling I had when I first walked into my first rented flat in Covent Garden. A thrilling sense that this must be mine and no particular inclination to leave when I’d finished looking around.

We’d looked at all kinds of houses from manors and mansions to cottages and space age barn conversions – we’d got used to looking for ways to escape before we’d even been shown the best spare. When you get the feeling of not wanting to leave, you’ve found a home. And it doesn’t happen very much. Like meeting people you could fall in love with, or seeing chances to change your life. They’re bound to come along but never very often, and when they do come you’ve got to spot them and go after them with everything you’ve got, even if it makes you feel and look ridiculous – which is also pretty much guaranteed.

I liked that old farmer. He had a particular quality of serenity, as cool and powerful as the morning sun, and we were all instantly at ease in this cobble of buildings all clustered around an ancient well, fields stretching in all directions through pasture and woodland, bordered to the east by the road and the west by a river. It was the first house we’d seen that was obviously a reluctant sale. We’d walked around the place with him. He never said anything was wonderful or great or useful, like all of the other people had, but it all was. We’d sat in bright gold sunshine in the ramshackle kitchen having a cup of tea. It was just nice, merely nice but I knew I was having the feeling. The feeling of wanting to stay somewhere. And as I rolled up the drive I was having the feeling again. I wanted to stay. It was enough to make my heart beat faster in the silence. I didn’t even care about the car. I was where I wanted to be. I didn’t know my way around the place. I knew I wanted it the moment I arrived. I’d been back three times and still only scratched the surface. There were a lot of rooms, a lot of buildings, most of which I still hadn’t even set foot in.

It was a mad jumble of endless compartments and spaces. If you included every building there must have been way more than a hundred rooms. Not one of them was very grand, and only the kitchen, the bathroom and one of the bedrooms in the farmhouse itself had recently been in use. There were so many outbuildings, a bewildering amount, it was more like a village than a house, really. Many stone and slate stables falling into disrepair. Endless empty structures snaking around overgrown courtyards. Everything from a cathedral-sized stone barn that looked as permanent as a mountain, to something that had been made out of telegraph poles and bits of railway line, and was about to collapse at any moment. There was a vast, rusting modern agricultural hangar big enough to park the space shuttle. There were towering corrugated sheds. The farmer had sold his cattle some weeks before and the whole place had ground to a halt: slightly eerie. There were sheep out in the fields in the middle distance – the fields were rented out temporarily to a neighbouring sheep farmer – but the buildings were in decline and obviously had been for some time. I still meet people from time to time who say, ‘Oh yes, you live on the heath, don’t you? Well, we looked at it, you know.’ Too big. Too complicated. Unmanageable. Impractical. And shake their heads.

It surprised me, actually, quite how nasty it all was, now I was faced with it alone: asbestos, concrete clamps and slurry pits, no garden to speak of. There was the remains of a walled garden, but it was completely derelict now, just a red brick wall remained. Toppling half-demolished sheds obscured every outlook. There was a concrete slab as big as a football pitch just outside the back door, and the back door didn’t lock. There was no lock on it. If you approached the house from the right direction, you could just let yourself in. It was a long way from Covent Garden. I didn’t know places like this still existed.

As well as buildings there were heaps. The place was characterised, really, by its heaps. Heaps are a feature of farms, just as much as hedges and cows are. Where there is a farm there are always heaps. There were piles of logs, piles of sacks, piles of manure – the farmer had emptied out the old slurry pit and made an enormous cowpat. That was one of the biggest heaps. I wasn’t sure what it was but my natural inclination was to climb it. It was a magnificent five-storey whopper. I began to scramble up the side, but two steps in, I was up to my knees. A crust had formed, but underneath it was still very sloppy and warm. It was like a pie. A pie made from the accumulated mess of twenty years of intensive cow farming.

Inside the sheds were piles of bricks, pallets of Cotswold stone, many different species of roof tiles, doors, boards, and timbers divided into oak, elm and pine. Farmers have always managed to recycle just about everything. Apart from old tyres. No one has thought of a use for old tyres, but farmers still tend to hang on to them, perhaps because they know that time will come. There was another, newer pile, which seemed to be horse related. This was fresh, and quite obviously still in business as a pile, still steaming. The farmer and his wife kept horses and had housed them at the farm until the last possible minute. Maybe they’d ridden off on them that very morning. There was a big mountain of rubble next to the horse manure and that was clearly my best pile. There was enough rubble there to make me feel confident. It was reassuring just to have so much of something all in a nice pile. Even rubbish. It wasn’t very pretty to look at, that one, but I climbed to the top and everything else looked pretty from there.

You get heaps when there’s building work going on, and there always is on farms. Farm is another word for a building site. The first building gangs were actually farmers. Farm workers built barns in the winter months when there was not much farming going on. Actually, stuff pretty much just grows by itself anyway. Farming really means taking care of everything else. That’s the tricky bit. There is always something leaking, falling over or blowing away on a farm, and building, rebuilding, patching and fixing are a continuous cycle.

There was a great view of everything from the top of my heap of rubble. I had a good look at the house. It stood right in the middle of the piles of muck, debris and ugly modern concrete slabs. Although it needed new windows you could tell it had started out, and remained, beautiful to the core. The Cotswold type of house is a beautiful thing. Built to last, built with stone and roofed with stone. Stone roofs held in place by great timbers from woods nearby and from old ships that had once sailed the oceans, now come to rest. The stone roof slates were a mosaic of a million greys, practically alive with moss, and gold and silver lichen, a part of the landscape. It had been built with care, and from where I was standing the roof looked like a work of art and emphasised the sense of shelter a home provides. There it was.

The house didn’t look in too bad shape. It was a typical rambling farmhouse with rooms and corridors everywhere, apparently at random. Plaster was coming away from the walls in places. Without the plaster, you could see that some of the beams were maybe a little bit rotten. Now I considered it, the roof looked like it probably needed replacing. The walls were good, mainly, apart from the damp, which made them smell. We’d more or less have to rebuild the whole house, I thought, as I stood there.

The picture was clearer from above. From my vantage point on top of the pile in the stillness, the wonderful whirring silence, I could take it all in. I suddenly felt slightly overwhelmed by my new life. I’d been here a few times but it was only from up here that the scale of the place became apparent. The red brick wall showed there must have once been a garden, as I thought. There were three courtyards of stone stables. The courtyards were all completely unexplored. They were kind of bundled in with the house. They’d all have to find some kind of use eventually, but for now they stood in ruin. I tiptoed over to the other side of the pile to check over the roofs. I knew the roof is always the first thing you have to take care of. As long as the roof is OK a building can sit there for years. The roofs were bad. I knew that anyway, I just thought I’d check. There were holes in all of them, except one stable with a clear plastic roof right next door to the house. It was full of plants and flowers. There was a pond in that room too, with goldfish in.

I slid down the pile and headed for the overgrown tangle of garden. I might never have known, as I know now, that at one time the farm had several gardens. I only found out because of an elderly lady who came to visit a short time after we arrived.

Tiny and delicate, pretty and frail as lace, her eyes darted everywhere. I’d hung on every word she’d said. She told me she was born in the bedroom, and she was still interested in the farm as if it was a person she had once been in love with. ‘Oh, there was such a lovely nuttery in that meadow.’ She talked about playing in vast orchards behind the walled flower garden and a kitchen garden, which was now completely extinct, concreted over in fact. There had been a tennis court. In one of the fields there had even been a cricket pitch, complete with a pavilion. I’ve been trying to find that cricket pitch ever since.

As it was now, it was like I’d stepped out of time: a hundred creaking empty rooms and a garden that had been asleep for a hundred years. It was a ghost ship in the sleepy spell of late summer. In the forgotten overgrown corner of the garden, I had to remember to keep my mouth shut when I was walking around to stop flies going in. There seemed to be so many different sorts. The air was thick with them. I swallowed several, which was so horrible it made me shout out loud. It was beautiful, too, but we never shout out loud for beauty when we are alone. Not normally. I was so excited. I shouted. I knew no one could hear. It was breathtaking. Oxeye daisies, those really big tall ones, stood absolutely motionless and inexplicable in gold, waist-deep grass. In the shady corners, the concrete slabs of the old bull pens were being colonised by a creeping moss. There’s nothing like moss. It exists at a different scale to the rest of the world. I got down on my knees to look at it more closely. The spiralling chaos of the tiny shoots spoke its own strange language. It seemed to communicate directly with the part of the brain that deals with roofs, and told it not to worry. The top ten most wanted enemies of the gardener had all set up shop and were all looking quite magnificent. There was a thistle rising to head height in full flower. Sticky willy, ivy, granny-pop-out-the-bed and nettles, the charging cavalry of English undergrowth, had been waging war all summer long but now territories were established, and there was a sense of balance and bounty that formal gardens lack.

The superficial silence resolved into the whirr of a myriad living things. There were butterflies and blue tits. There were rooks and rats. The farmer and his wife had shipped out to Stow-on-the-Wold some weeks earlier just leaving the horses so the house was unlived in. Unlived in by people. Everywhere had something living in it. Birds were all over the place like a gas: innumerable different sorts, from tiny whizzing whirling ones to big gliding bombers. I know now that you can always hear birds singing here, but you don’t always notice them. It’s the opposite of traffic noise. Calming. There were toads under flowerpots. Untold numbers of rabbits bobbed around. The place was empty but ringing with life. I was surprised to see a lizard. I thought they lived only on rocks and in jungles. This one was on the wall in the shade. The insects were much weirder than I had bargained for. A wasp as big as my thumb appeared, angry that I had shifted the balance as I beat a path through the tall grasses.

I was completely alone in deep silence. No taxis. No shops. No cappuccino. No adverts. Just space and peace, and it was all right. I wandered further from the house. The afternoon air was heavy with haze and buzzing. I turned this way and that way, wandering dazed and blissful around another blind corner of the slumbering afternoon. Suddenly there was a blackberry bush as big as a bus, festooned over some hidden banister of shrubbery, decorated with fruit, as festive as Christmas and about twice as delightful for being completely unexpected. I caught an overpowering biff of blackberry smell and it was like being shunted by that white van, now a long way away. Just an hour and a half from London, but another world. I’ve since come to appreciate that stumbling on unexpected blackberry bushes in full fruit, especially when slightly out of breath, is one of the great delights of nature; a sensory sensation, a smell like a magic spell. Close eyes, deep breath. Better than drugs or dreams.

It was a magnificent spectacle. I’d hardly given blackberries a thought since I was ten. I’d spent my entire adult life in cities. My dad was a fanatical blackberry picker and we used to go all the time when I was a kid, but I’d never, ever seen a bush like this on any of those happy expeditions. And there it was, deep in the countryside in the deepening afternoon sun: the quintessential specimen of English flora at its zenith. Overlooked, the bramble. The leaves, a shade of green seen nowhere outside English woodland; the black and red berries, almost psychedelic. I had to stop because of the smell more than anything. I hadn’t ever smelled anything like that. Well, maybe when I was a child. All you can smell in cities is drains and food and exhausts. I was transported back to my childhood the moment the first blackberry juice ran down my chin. I stood ecstatic, beyond time. The overgrown garden seemed suddenly to be a kind of Tudor scenario. I stood there smiling, chewing blackberries, half expecting Henry VIII to ride around the corner.

I was surprised then, to find a fig tree. I thought that like lizards, they only grew on desert islands. Now I look forward to warm figs from the vine every year in the way I used to look forward to playing in New York City. Figs soften the blow of the end of summer, with their biblical glamour and intriguing insides. I had a rustle around in the friendly boughs expecting to find they were all still as hard as walnuts, but they were soft, ready. I shared them with the wasps.

If César Ritz had surprised me with an unexpected breakfast in bed, I couldn’t have felt any more elevated than I did as I wandered into the apple trees. I didn’t even know there were any. Orchards are enchanting places. Eden was an orchard. There were maybe a dozen trees standing in patient, orderly rows, bursting with bonsai vigour and laden with fruit. So very pretty. I laughed out loud as I pulled a dangling apple from one of those boughs. I felt in touch with something very big and benign.

In shops, apples all have to be exactly the same size. Shops would probably prefer it if apples were cube shaped so they could fit more in a crate, but I soon discovered that the small ones are the best. They are cuter and they are sweeter. There were four different kinds of apple in the little orchard and they were all as different as cheese and onion and salt and vinegar. There was a mist on the cherry-red skins. I’ve since learned it’s natural yeast. I polished a red one to a deep purple shine on the corner of my shirt.

The joy of fruit trees is profound. They need very little looking after. All they require is the odd haircut. No primping, feeding or weeding. Every year, they bounce back and knock me over with their bounty.

Full of apples, I wandered over to the giant sequoia, the vast tree that dominated the landscape, to see the sun go down. The giant sequoia is the largest living thing on the planet. There’s quite a well-known photo of one with a road going through the middle. They come from north-west America, but are fairly common in this country. Great avenues of them line the drives of stately homes like moon rockets, skewing the scale of everything. You see odd specimens in parkland dwarfing the ancient oaks. The farmer had told me it was supposed to be the tallest tree in Oxford, but he may have been mistaken. For starters, it’s clearly not in Oxford, Oxford is twenty miles away, but it is definitely tall, visible for miles around, straight and narrow as an arrow but leaning gently to one side. It set the tone for the whole farm really, that wonkiness. You could never be too precious living in the shadow of a vast, beautiful and lopsided tree. It towered over everything. I thought it must be hundreds of years old, but it turned out to be a mere sapling. There was one planted on each of the farms in the neighbourhood in the twenties. They can live for up to two and a half millennia but this was the sole survivor. They get struck by lightning and fall. If this one fell on the house it would be all over. Although it was leaning away and pretty unlikely to topple in the wind, it was hard to say what might happen in a lightning strike.

I gradually came under its spell as I stood there. I love that tree. It’s the first thing I look for when I’m coming home, the first thing I see when I walk out the front door. It swayed in the breeze. It’s swaying in the breeze now. Some people came round a few months ago. They said they wanted to tell me that the man who planted the tree had died, but I think they were just being nosey. I wanted to say ‘That’s a shame, I would have liked to ask him why he planted something that will be as large as the Eiffel Tower one day, quite so close to my house,’ but I managed to contain myself. It was puzzling why this colossal thing had been plonked on the doorstep. There were so many other places it could have gone. That was the perfect spot for a magnolia, not for a Tree-Rex. So many of the problems faced by farmers now are due to that kind of short-sightedness in previous generations.

I’d put my marker down on two hundred acres of England, but I still wasn’t clear exactly how big an acre was. Very few people seem to know what an acre is any more. Even the estate agent couldn’t help me there. Someone had told me Soho was about 140 acres, but it was part of a different planet. Here I was. Alone and quite liking it. I drifted across another huge concrete slab – it was instantly clear how much farmers love concrete – but beyond the huge tiles of the cast concrete pads, tessellating meadows and fields, so inviting: all that space, after being cooped up in a city for so long. I was totally, utterly, completely and blissfully clueless about farming; about building, about animal husbandry and gardens. Hedging, ditching and dry stoning all sounded like medieval forms of capital punishment. But the idea of having some land to play with was just enough to stop me being scared of what I’d done, which was to cash in all my chips for a vast ship that had foundered, run aground and, however magnificent it was, was beginning to sink.

I spent the days wandering the land, and the evening hours gazing at old drawings of the farm buildings and maps. The farmer had handed me a battered document folder full of well-thumbed drawings and plans stretching back a hundred years or so. There was also a map showing what the parish looked like a hundred years before that – almost exactly the same as it does now: it had the same field boundaries, the same roads and paths, even the ditches and drains were the same. The village was all there and just the same size. It was obvious just from wandering around though, that the valley had been under cultivation for millennia. There were a couple of fields of ‘ridge and furrow’, the remains of the farming system of the Middle Ages. There was an ‘S’-shaped field. When a field is ‘S’-shaped, it means it was ploughed by oxen so it would be very old indeed. There were ancient tumuli, standing stones and even one or two lesser known stone circles from the mists of time dotted around the parish. The oldest part of the farmhouse was the bit right next to the well and was probably built as a gamekeeper’s cottage deep in the Wychwood Forest in the 1600s – I loved the way no one knew. There were wells all around the barnyard. Every time I dug a new hole, I found a well – they are still turning up. I found another one just last month: wells and drains, everywhere. The architecture of the farm wasn’t just the stuff you could see. There was lots of stuff underground, too. It had proper sewers that, fortunately, all seemed to be working perfectly.

I’d bought a knackered cattle farm, but a hundred years ago when it was a small part of a vast feudal estate, it would have been knocking out a bit of everything. There would have been chickens, geese and ducks. A pigsty. Back then, it was home to a notable Shorthorn dairy herd. There would have been sheep for wool and for meat, as well as the extinct nuttery and the long gone orchards. A few dozen people would have worked here, taking care of the stock and tending arable crops: fodder for the animals, as well as cereal crops for the household and for market. There had been a bakery – I found the traces of the huge old bread oven, a sooty shadow on a wall – and a dairy that would have produced cheese and butter. Basically, it would have created more or less everything you can find in an upmarket delicatessen in Islington.

Over the last hundred years agriculture has changed beyond all recognition. Within living memory, fields were all ploughed by horse-drawn equipment: now it’s all about space age technology; combine harvesters linked by computers to satellites. Farms used to produce a wide variety of crops, but recently farmers have tended to concentrate on just doing one thing – watching machines. There are fewer farm workers and the countryside is peppered with beautiful, but redundant farm buildings. It’s easy to make stuff grow, but it’s very hard to make money from farming.

Even vegetable gardens, once such practical things, have become quite whimsical luxuries. In terms of cost, it really doesn’t make sense to grow your own vegetables. Allotments are popular but no one grows their own to save money. They do it because they like it.

I suppose I was coming at the place from a different perspective than anyone who had ever worked here, seeing its resources from a tourist’s point of view, with a sense of wonder at all the stuff that had accumulated as the wheels of agriculture had begun to turn faster and faster. I hired someone to help, a farm manager, but he clearly thought I was mad and left after a week. I continued poking around and turned up all kinds of treasure. I found a steel chopper, a scythe, in an old shed, it was rusty, but beautifully made and the blade, when sharpened, was the finest piece of steel I’ve ever seen. I didn’t find the old cricket pitch. But after a bit more poking around I did find the remains of a motte and bailey in the railway field – a Norman castle. It had just been sitting there quietly all along.

There was a river. I’d asked the farmer if there were fish in it. He said he thought so but that he’d never had time to go fishing. This seemed crazy. The river frontage was one of the main reasons that I bought the farm. What a thing to have! A river. There was about a quarter of a mile of the Evenlode. It was soon obvious that I would never have time to go fishing either, but the river was a source of hope, the only thing that really seemed to work in the whole place – the only thing I could trust to do what it was supposed to do and not break down, fall over or need servicing. It’s been rolling happily down the border of the farm for centuries and will do for centuries to come.

There was a railway line following the river and an eight-acre wood backing on to the railway line. Eight acres of ancient woodland: eight city blocks of the European equivalent of tropical rainforest. Giant puffballs, strange toadstools, thriving in the tangle and orchids, among the remains of rusting pheasant pens, a big pile of green tyres and a mess of rooks. I only found out for sure it was ancient woodland later but the very first time I fought my way in there, it was clear it was primordial. To enter, was to step inside another world with a slightly different climate. Even at the end of a hot summer, in places it was still really quite boggy among the oak trees. The place hadn’t been cultivated for decades, hadn’t been touched. A dashing hare, a dancing weasel, but no people had been in there for years.

The last few owners had more pressing concerns. Even the farmer before the one I bought the place from, had been chasing his tail. He’d chopped down fifty acres of ancient woodland but there was still a handful of the old forest left. He must have known it was vital. And it was. It was smaller than it had been, but once inside it felt like it went on forever and there was nowhere else in the world; a bit like when you’re in Selfridges.

I was used to being one of a crowd. I rarely spent much time alone. The more it was very still and very quiet, the less I seemed to notice I was on my own.

I’d been on endless loops of world tours – passing through hotel rooms, ballrooms and bedrooms – but now I felt anchored to something. The river, those woods and fields, but mainly to my wife. I loved her. It was a combination of things that brought me to a standstill, snapped me to my senses. As a travelling man, I suppose I led many lives simultaneously and didn’t take any of them particularly seriously, but now I got to work, thinking with all my might: new home, newly wed, new job. There were a lot of puzzles to solve. My friends all thought I had gone mad, and I had. Love does that. Every shed was a new possibility and for the first time in my life, at the age of thirty-two, I began to get out of bed early. I was always busy. I became absorbed by everything about the place, even the weather. I spent the evenings researching wind speed gauges and rainfall indicators as the heat of the summer began to disperse. The colours changed, and the supreme calm of late September cast its spell over the farm as the haze of summer gradually cleared. The distant horizon emerged in sharp focus and I could glimpse stately homes on their hilltops. The whole landscape softened, all the hard edges obscured by seeding grasses and haywire shrubs. Those derelict buildings full of birds, butterflies and dragonflies, silver sunlight and long shadows, standing still in a strong breeze. The leaves on the fruit trees were starting to droop, yellow and drop. While dawdling in the garden I spotted, picked and ate a solitary apple – a real beauty that had been missed, high up, hidden by leaves until just then. It was only a couple of weeks ago that high summer had its moment, but the blackberries now seemed to belong to a different world, another time and place altogether. Other than that apple and a few cheerful bright jewels of alpine strawberries, there was just the pear tree with its bounty still intact, dangling from almost bare branches, like upside down balloons. The garden party was over.

It was the very last firework of summer, that pear tree. It’s miraculous really. I was sure that, like the rest of the garden, it had had little or no attention over the year, or years past. But it was spectacular. I’ve never had pears quite that juicy.

A fire burned in the grate as I picked every last one, a great big basketful: all shapes and sizes, some long and thin like sausages, and some almost completely round, like dumplings, but somehow still all very clearly pear-like. I couldn’t resist eating the little tiny ones while I was out there. The biggest nobbly ones we sliced, seasoned, sloshed with oil and roasted on the fire. Eating them with sticky fingers in a silent huddle, feeling the little kicks in Claire’s tummy, watching the flames and listening to the rain as the wind rattled the windows.

And that was it. All of a sudden, snap, the nights drew in. A cold wind rolled in from the east. The lawn was a carpet of leaves and broken rose petals. We’d been living in the garden as much as the house, but from now until the spring we’d be holed up in the draughty house.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: