скачать книгу бесплатно

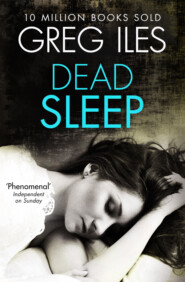

Dead Sleep

Greg Iles

Terrifying secrets and a stunning mystery power this page-turner from the New York Times No.1 bestseller.Objects of desire… or death?When prize-winning photojournalist Jordan Glass chances upon a portrait by an unknown artist in Hong Kong, she is shocked. The face staring back at her is her missing identical twin sister.The painting is part of an exhibition entitled ‘Sleeping Women’ and Jordan realizes that the portraits are all of women who have recently disappeared from New Orleans. Electrifying a case previously paralysed by a lack of bodies, this new evidence spurs the FBI’s serial killer unit into action.Working with the FBI, Jordan becomes both hunter and hunted in search for the artist- and is forced to confront terrifying secrets about her past in a final stunning showdown.

GREG ILES

Dead Sleep

Dedication (#ulink_295a6467-f9ce-5acf-bdc4-a58de62a7757)

In memory of

Silous Marty Kemp

Table of Contents

Cover (#ude91a724-2970-5cd7-9b34-31bf02e2b34c)

Title Page (#u954f21ce-500e-5d16-b658-42ba183d8d2c)

Dedication (#u1116073d-e722-5f11-b56b-0ae199c5a923)

Chapter One (#u0d0f667f-7b82-5358-aad8-49fa02f878e4)

Chapter Two (#u28e00b30-088f-5266-8ddd-a06d119590e9)

Chapter Three (#u88b86c9c-997b-547e-a90f-aba86f41fe86)

Chapter Four (#u41407688-18e1-5dd3-b6fb-9e3cfe0e5fb2)

Chapter Five (#uc28d9334-9eaa-57e4-8cfb-c559083b8634)

Chapter Six (#u0d601d2d-8d42-5b79-b166-d607c89a139a)

Chapter Seven (#u9d1bad3e-d193-59c7-958b-f75a72182b97)

Chapter Eight (#uaf787b6c-ac46-5b72-b9a2-b2313b719b37)

Chapter Nine (#ueca44af4-e6d4-5ded-bbe2-8e479c373297)

Chapter Ten (#ufdf7e9cc-c9ec-5701-aba2-ddb31c5b26bc)

Chapter Eleven (#u9e26da41-6a67-5fbf-a990-7975a30bc3db)

Chapter Twelve (#u0e3e1648-11a1-5c62-a2a1-a1d1a4650cfe)

Chapter Thirteen (#u95c32236-e4ff-5d3d-9cc5-ccec259292dd)

Chapter Fourteen (#ub9720e10-81aa-5af0-b063-4cebd3eb5301)

Chapter Fifteen (#u66fed3ab-ee54-539f-bc17-c0160a0f75c0)

Chapter Sixteen (#u616703d7-c338-54b1-ab5e-aa4043141279)

Chapter Seventeen (#uc86e87d0-9edd-5628-9f15-4b08716f2d27)

Chapter Eighteen (#u02a0dde8-c0b8-57f2-a57a-30c40b5a8b37)

Chapter Nineteen (#u7309cca4-bd98-5cbf-b810-3105421970af)

Chapter Twenty (#u65f404cb-7898-54cc-8871-da984e840d1c)

Chapter Twenty-One (#u433b9451-4db3-5496-9a8a-e8b6d9458d0a)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#u5ce09e7e-45ee-54b5-84dc-8c2b4f0e1d4a)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#u32699832-f695-5782-9de9-1f08e6730722)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#u896cec35-1c9e-501d-a9f3-6eed4f79fe21)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#uf8696fbd-ae57-57e9-979b-6a303e32f077)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#u7ab7b31e-a2f8-54d1-8e82-8fb064691379)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#uf2594307-47ea-53c5-b7e3-de30ee9fcea8)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#ub82679d7-80a2-5481-9c20-3502878318cd)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#ua83ba19a-ec17-5b72-9a7d-5f85e50672a3)

Acknowledgments (#u3234ca0a-55b7-595e-9475-fdc36c6baaa4)

About the Author (#ub4eb19fd-037f-5e66-8f34-32e204b47df4)

Books By Greg Iles (#u059aac38-3b81-56a0-9009-bd8273aa4734)

Copyright (#u815d6fdb-24e8-5cff-894b-4a9d9c197db7)

About the Publisher (#ucc3a53a9-e4bc-5081-98f3-bc59875255b3)

ONE (#ulink_2b5f0755-4e4a-519a-a2d4-11cf1ccef6fc)

I stopped shooting people six months ago, just after I won the Pulitzer Prize. People were always my gift, but they were wearing me down long before I won the prize. Still, I kept shooting them, in some blind quest that I didn’t even know I was on. It’s hard to admit that, but the Pulitzer was a different milestone for me than it is for most photographers. You see, my father won it twice. The first time in 1966, for a series in McComb, Mississippi. The second in 1972, for a shot on the Cambodian border. He never really got that one. The prizewinning film was pulled from his camera by American Marines on the wrong side of the Mekong River. The camera was all they found. Twenty frames of Tri-X made the sequence of events clear. Shooting his motor-drive Nikon F2 at five frames per second, my dad recorded the brutal execution of a female prisoner by a Khmer Rouge soldier, then captured the face of her executioner as the pistol was turned toward the brave but foolish man pointing the camera at him. I was twelve years old and ten thousand miles away, but that bullet struck me in the heart.

Jonathan Glass was a legend long before that day, but fame is no comfort to a lonely child. I didn’t see my father nearly enough when I was young, so following in his footsteps has been one way for me to get to know him. I still carry his battle-scarred Nikon in my bag. It’s a dinosaur by today’s standards, but I won my Pulitzer with it. He’d probably joke about the sentimentality of my using his old camera, but I know what he’d say about my winning the prize: Not bad, for a girl.

And then he’d hug me. God, I miss that hug. Like the embrace of a great bear, it swallowed me completely, sheltered me from the world. I haven’t felt those arms in twenty-eight years, but they’re as familiar as the smell of the sweet olive tree he planted outside my window when I turned eight. I didn’t think a tree was much of a birthday present back then, but later, after he was gone, that hypnotic fragrance drifting through my open window at night was like his spirit watching over me. It’s been a long time since I slept under that window.

For most photographers, winning the Pulitzer is a triumph of validation, a momentous beginning, the point at which your telephone starts ringing with the job offers of your dreams. For me it was a stopping point. I’d already won the Capa Award twice, which is the one that matters to people who know. In 1936, Robert Capa shot the immortal photo of a Spanish soldier at the instant a fatal bullet struck him, and his name is synonymous with bravery under fire. Capa befriended my father as a young man in Europe, shortly after Capa and Cartier-Bresson and two friends founded Magnum Photos. Three years later, in 1954, Capa stepped on a land mine in what was then called French Indochina, and set a tragic precedent that my father, Sean Flynn (Errol’s reckless son), and about thirty other American photographers would follow in one way or another during the three decades of conflict known to the American public as the Vietnam War. But the public doesn’t know or care about the Capa Award. It’s the Pulitzer they know, and that’s what makes the winners marketable.

After I won, new assignments poured in. I declined them all. I was thirty-nine years old, unmarried (though not without offers), and I’d passed the mental state known as “burned out” five years before I put that Pulitzer on my shelf. The reason was simple. My job, reduced to its essentials, has been to chronicle death’s grisly passage through the world. Death can be natural, but I see it most often as a manifestation of evil. And like other professionals who see this face of death—cops, soldiers, doctors, priests—war photographers age more rapidly than normal people. The extra years don’t always show, but you feel them in the deep places, in the marrow and the heart. They weigh you down in ways that few outside our small fraternity can understand. I say fraternity, because few women do this job. It’s not hard to guess why. As Dickey Chappelle, a woman who photographed combat from World War II to Vietnam, once said: This is no place for the feminine.

And yet it was none of this that finally made me stop. You can walk through a corpse-littered battlefield and come upon an orphaned infant lying atop its dead mother and not feel a fraction of what you will when you lose someone you love. Death has punctuated my life with almost unbearable loss, and I hate it. Death is my mortal enemy. Hubris, perhaps, but I come by that honestly. When my father turned his camera on that murderous Khmer Rouge soldier, he must have known his life was forfeit. He shot the picture anyway. He didn’t make it out of Cambodia, but his picture did, and it went a long way toward changing the mind of America about that war. All my life I lived by that example, by my father’s unwritten code. So no one was more shocked than I that, when death crashed into my family yet again, the encounter shattered me.

I limped through seven months of work, had one spasm of creativity that won me the Pulitzer, then collapsed in an airport. I was hospitalized for six days. The doctors called it post-traumatic stress disorder. I asked them if they expected to be paid for that diagnosis. My closest friends—and even my agent—told me point-blank that I had to stop working for a while. I agreed. The problem was, I didn’t know how. Put me on a beach in Tahiti, and I am framing shots in my mind, probing the eyes of waiters or passersby, looking for the life behind life. Sometimes I think I’ve actually become a camera, an instrument for recording reality, that the exquisite machines I carry when I work are but extensions of my mind and eye. For me there is no vacation. If my eyes are open, I’m working.

Thankfully, a solution presented itself. Several New York editors had been after me for years to do a book. They all wanted the same one: my war photographs. Backed into a corner by my breakdown, I made a devil’s bargain. In exchange for letting an editor at Viking do an anthology of my war work, I accepted a double advance: one for that book, and one for the book of my dreams. The book of my dreams has no people in it. No faces, anyway. Not one pair of stunned or haunted eyes. Its working title is “Weather.”

“Weather” was what took me to Hong Kong this week. I was there a few months ago to shoot the monsoon as it rolled over one of the most tightly packed cities in the world. I shot Victoria Harbor from the Peak and the Peak from Central, marveling at the different ways rich and poor endured rains so heavy and unrelenting that they’ve driven many a roundeye to drunkenness or worse. This time Hong Kong was only a way station to China proper, though I scheduled two days there to round out my portfolio on the city. But on the second day, my entire book project imploded. I had no warning, not one prescient moment. That’s the way the big things happen in your life.

A friend from Reuters had convinced me that I had to visit the Hong Kong Museum of Art, to see some Chinese watercolors. He said the ancient Chinese painters had achieved an almost perfect purity in their images of nature. I know nothing about art, but I figured the paintings were worth a look, if only for some perspective. Boarding the venerable Star Ferry in the late afternoon, I crossed the harbor to the Kowloon side and made my way on foot to the museum. After twenty minutes inside, perspective was the last thing on my mind.

The guard at the entrance was the first signpost, but I misread him completely. As I walked through the door, his lips parted slightly, and the whites of his eyes grew in an expression not unlike lust. I still cause that reaction in men on occasion, but I should have paid more attention. In Hong Kong I am kwailo, a foreign devil, and my hair is not blond, the color so prized by Chinese men.

Next was the tiny Chinese matron who rented me a Walkman, headphones, and the English-language version of the museum’s audio tour. She looked up smiling to hand me the equipment; then her teeth disappeared and her face lost two shades of color. I instinctively turned to see if some thug was standing behind me, but there was only me—all five-feet-eight of me—thin and reasonably muscular but not much of a threat. When I asked what was the matter, she shook her head and busied herself beneath her counter. I felt like someone had just walked over my grave. I shook it off, put on the Walkman, and headed for the exhibition rooms with a voice like Jeremy Irons’s speaking sonorous yet precise English in my headphones.

My Reuters friend was right. The watercolors floored me. Some were almost a thousand years old, and hardly faded by the passage of time. The delicately brushed images somehow communicated the smallness of human beings without alienating them from their environment. The backgrounds weren’t separated from the subjects, or perhaps there was no background; maybe that was the lesson. As I moved among them, the internal darkness that is my constant companion began to ease, the way it does when I listen to certain music. But the respite was brief. While studying one particular painting—a man poling along a river in a boat not unlike a Cajun pirogue—I noticed a Chinese woman standing to my left. Assuming she was trying to view the painting, I slid a step to my right.

She didn’t move. In my peripheral vision, I saw that she was not a visitor but a uniformed cleaning woman with a feather duster. And it wasn’t the painting she was staring at as though frozen in space, but me. When I turned to face her, she blinked twice, then scurried into the dark recesses of the adjoining room.

I moved on to the next watercolor, wondering why I should transfix her that way. I hadn’t spent much time on hair or makeup, but after checking my reflection in a display case, I decided that nothing about my appearance justified a stare. I walked on to the next room, this one containing works from the nineteenth century, but before I could absorb anything about them, I found myself being stared at by another blue-uniformed museum guard. I felt strangely sure that I’d been pointed out to him by the guard from the main entrance. His eyes conveyed something between fascination and fear, and when he realized that I was returning his gaze, he retreated behind the arch.

Fifteen years ago, I took this sort of attention for granted. Furtive stares and strange approaches were standard fare in Eastern Europe and the old Soviet Union. But this was post-handover Hong Kong, the twenty-first century. Thoroughly unsettled, I hurried through the next few exhibition rooms with hardly a glance at the paintings. If I got lucky with a cab, I could get back to the ferry and over to Happy Valley for some sunset shots before my plane departed for Beijing. I turned down a short corridor lined with statuary, hoping to find a shortcut back to the entrance. What I found instead was an exhibition room filled with people.

Hesitating before the arched entrance, I wondered what had brought them there. The rest of the museum was virtually deserted. Were the paintings in this room that much better than the rest? Was there a social function going on? It didn’t appear so. The visitors stood silent and apart from one another, studying the paintings with eerie intensity. Posted above the arch was a Lucite plaque with both Chinese pictographs and English letters. It read:

NUDE WOMEN IN REPOSE

Artist Unknown

When I looked back into the room, I realized it wasn’t filled with “people”—it was filled with men. Why men only? I’d stayed a week in Hong Kong on my last visit, and I hadn’t noticed a shortage of nudity, if that was what they were looking for. Every man in the room was Chinese, and every one wore a business suit. I had the impression that each had been compelled to jump up from his desk at work, run down to his car, and race over to the museum to look at these paintings. Reaching down to the Walkman on the waistband of my jeans, I fast-forwarded until I came to a description of the room before me.

“Nude Women in Repose,” announced the voice in my headset. “This provocative exhibit contains seven canvases by the unknown artist responsible for the group of paintings known popularly as the ‘Sleeping Women’ series. The Sleeping Women are a mystery in the world of modern art. Nineteen paintings are known to exist, all oil on canvas, the first coming onto the market in 1999. Over the course of the nineteen paintings, a progression from vague Impressionism to startling Realism occurs, with the most recent works almost photographic in their accuracy. Though all the paintings were originally believed to depict sleeping women in the nude, this theory is now in question. The early paintings are so abstract that the question cannot be settled with certainty, but it is the later canvases that have created a sensation among Asian collectors, who believe the paintings depict women not in sleep but in death. For this reason, the curator has titled the exhibit ‘Nude Women in Repose’ rather than ‘Sleeping Women.’ The four paintings that have come onto the market in the past six months have commanded record prices. The last offering, titled simply Number Nineteen, sold to Japanese businessman Hodai Takagi for one point two million pounds sterling. The Museum is deeply indebted to Mr. Takagi for lending three canvases to the current exhibit. As for the artist, his identity remains unknown. His work is available exclusively through Christopher Wingate, LLC, of New York City, USA.”

I felt a surprising amount of anxiety standing on the threshold of that roomful of men, silent Asians posed like statues before images I could not yet see. Nude women sleeping, possibly dead. I’ve seen more dead women than most coroners, many of them naked, their clothes blasted away by artillery shells, burned off by fire, or torn away by soldiers. I’ve shot hundreds of pictures of their corpses, methodically creating my own images of death. Yet the idea of the paintings in the next room disturbed me. I had created my death images to expose atrocities, to try to stop senseless slaughter. The artist behind the paintings in the next room, I sensed, had some other agenda.

I took a deep breath and went in.

My arrival caused a ripple among the men, like a new species of fish swimming into a school. A woman—especially a roundeye woman—clearly made them uncomfortable, as though they were ashamed of their presence in this room. I met their fugitive glances with a level gaze and walked up to the painting with the fewest men in front of it.

After the soothing Chinese watercolors, it was a shock. The painting was quintessentially Western, a portrait of a nude woman in a bathtub. A roundeye woman like me, but ten years younger. Maybe thirty. Her pose—one arm hanging languidly over the edge of the tub—reminded me of the Death of Marat, which I knew only from the Masterpiece board game I’d played as a child. But the view was from a higher angle, so that her breasts and pubis were visible. Her eyes were closed, and though they communicated an undeniable peace, I couldn’t tell whether it was the peace of sleep or of death. The skin color was not quite natural, more like marble, giving me the chilling feeling that if I could reach into the painting and turn her over, I would find her back purple with pooled blood.

Sensing the men close behind me edging closer, I moved to the next painting. In it, the female subject lay on a bed of brown straw spread on planks, as though on a threshing floor. Her eyes were open and had the dull sheen I had seen in too many makeshift morgues and hastily dug graves. There was no question about this one; she was supposed to look dead. That didn’t mean she was dead, but whoever had painted her knew what death looked like.

Again I heard men behind me. Shuffling feet, hissing silk, irregular respiration. Were they trying to gauge my reaction to this Occidental woman in the most vulnerable state a woman can be in? Although if she was dead, she was technically invulnerable. Yet this gawking at her corpse by strangers seemed somehow a final insult, an ultimate humiliation. We cover corpses for the same reason we go behind walls to carry out our bodily functions; some human states cry out for privacy, and being dead is one of them. Respect above all is called for, not for the body, but for the person who recently departed it.

Someone paid two million dollars for a painting like this one. Maybe even for this one. A man paid that, of course. A woman would have bought this painting only to destroy it. Ninety-nine out of a hundred women, anyway. I closed my eyes and said a prayer for the woman in the picture, on the chance that she was real. Then I moved on.

The next painting hung beyond a small bench set against the wall. It was smaller than the others, perhaps two feet by three, with the long axis vertical. Two men stood before it, but they weren’t looking at the canvas. They gaped like clubbed mackerel as I approached, and I imagined that if I pulled down their starched white collars, I would find gills. No taller than I, they backed quickly out of my way and cleared the space before the painting. As I turned toward it, a premonitory wave of heat flashed across my neck and shoulders, and I felt the dry itch of the past rubbing against the present.

This woman was naked as well. She sat in a window seat, her head and one shoulder leaned against the casement, her skin lighted by the violet glow of dawn or dusk. Her eyes were half open, but they looked more like the glass eyes of a doll than those of a living woman. Her body was thin and muscular, her hands lay in her lap, and her Victorian-style hair fell upon her shoulders like a dark veil. Though she had been sitting face-on to me from the moment I looked at the canvas, I suddenly had the terrifying sensation that she had turned to me and spoken aloud. The taste of old metal filled my mouth, and my heart ballooned in my chest. This was not a painting but a mirror. The face looking back at me from the wall was my own. The body, too, mine: my feet, hips, breasts, my shoulders and neck. But the eyes were what held me, the dead eyes—held me and then dropped me through the floor into a nightmare I had traveled ten thousand miles to escape. A harsh burst of Chinese echoed through the room, but it was gibberish to me. My throat spasmed shut, and I could not scream or even breathe.

TWO (#ulink_70b1a2a9-5264-589e-8563-573428e4e1dd)

Thirteen months ago, on a hot summer morning, my twin sister Jane stepped out of her town house on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans to run her daily three-mile round of the Garden District. Her two young children waited inside with the maid, first contentedly, then anxiously as their mother’s usual absence stretched beyond any they remembered. Jane’s husband Marc was working in blissful ignorance at his downtown law firm. After ninety minutes, the maid called him.

Knowing you could walk one block out of the Garden District and be in a free-fire zone, Marc Lacour immediately left work and drove the streets of their neighborhood in search of his wife. He cut the Garden District into one-block grids from Jackson Avenue to Louisiana and methodically drove them a dozen times. Then he walked them. He left the Garden District and questioned every porch-sitter, shade-tree mechanic, can kicker, crack dealer, and homeless person he could find on the adjoining streets. No one had heard or seen anything of Jane. A prominent attorney, Marc immediately called the police and used his influence to mount a massive search. The police found nothing.

I was in Sarajevo when Jane disappeared, shooting a series on the aftermath of the war. It took me seventy-two hours to get to New Orleans. By that time, the FBI had entered the picture and subsumed my sister’s disappearance into a much larger case, designated NOKIDS in FBI-speak, for New Orleans Kidnappings. It turned out that Jane was fifth in a rapidly growing group of missing women, all from the New Orleans area. Not one corpse had been found, so all the women were classified as victims of what the FBI called a “serial kidnapper.” This was the worst sort of euphemism. Not one relative had received a ransom note, and in the eyes of every cop I spoke to, I saw the grim unspoken truth: every one of those women was presumed dead. With no crime scene evidence, witnesses, or corpses to work with, even the Bureau’s vaunted Investigative Support Unit was stumped by the cold trail. Though women continued to disappear and still do, neither the Bureau nor the New Orleans police have come close to discovering the fate of my sister or any of the others.

I should clarify something. Not once since my father vanished in Cambodia have I sensed that he was truly dead, gone from this world. Not even with the last frame of film he shot showing an executioner’s pistol pointed at his face. Miracles happen, especially in war. For this reason I’ve spent thousands of dollars over the past twenty years trying to find him, piggybacking my money with that of the relatives of Vietnam-era MIAs, giving what would have been my retirement money to scam artists and outright thieves, all in the slender hope that one lead among the hundreds will turn out to be legitimate. On some level, my decision to take the advance for my book was probably a way to be paid to hunt for my father in person, to tramp across Asia with an eye to my camera and an ear to the ground.

With Jane it’s different. By the time my agency tracked me down on a CNN satellite phone in Sarajevo, something had already changed irrevocably within me. As I crossed a street once infested with snipers, a nimbus of dread welled up in my chest—not the familiar dread of a bullet with my name on it, but something much deeper. Whatever energy animates my soul simply stopped flowing as I ran, and the street vanished. I kept running blindly into the dark tunnel before me, as though it were nine years before, during the worst of it, when the snipers shot anything that moved. A CNN cameraman yanked me behind a wall, thinking I’d seen the impact of a silenced bullet on the concrete. I hadn’t, but a moment later, when the street returned, I felt as though a bullet had punched through me, taking with it something no doctor could ever put back or put right.

Quantum physics describes “twinned particles,” photons of energy that, even though separated by miles, behave identically when confronted with a choice of paths. It is now thought that some unseen connection binds them, defying known physical laws, acting instantaneously without reference to the speed of light or any other limit. Jane and I were joined in this way. And from the moment that dark current of dread pulsed through my heart, I felt that my twin was dead. Twelve hours later, I got the call.

Thirteen months after that—two hours ago—I walked into the museum in Hong Kong and saw her painted image, naked in death. I’m not sure what happened immediately after. The earth did not stop turning. The cesium atoms in the atomic clock at Boulder did not stop vibrating. But time in the subjective sense—the time that is me—simply ceased. I became a hole in the world.

The next thing I remember is sitting in this first-class seat on a Cathay Pacific 747 bound for New York, a Pacific Rim sunset flaring in my window as the four great engines thrum, their vibration causing a steady ripple in the scotch on the tray before me. That was two whiskeys ago, and I still have another nineteen hours in the air. My eyes are dry and grainy, stinging. I am cried out. My mind gropes backward toward the museum, but there is something in the way. A shadow. I know better than to try to force the memory. I was shot once in Africa, and from the moment the bullet ripped through my shoulder till the moment I came to my senses in the Colonial Hotel and found myself being patched up by an Australian reporter whose father was a doctor, everything was blank. The missing events—a hectic jeep ride down an embattled road, the bribing of a checkpoint guard (in which I participated)—only returned to me later. They had not disappeared, but merely fallen out of sequence.

So it was at the museum. But here, in the familiar environment of the plane, in the warm wake of my third scotch, things begin to return. Brief flashing images at first, then jerky sequences, like bad streaming video. I’m standing before the painting of a naked woman whose face is mine to the last detail, and my feet are rooted to the floor with the permanence of nightmares. The men crowding me from behind believe I’m the woman who modeled for the painting on the wall. They chatter incessantly and race around like ants after kerosene has been poured on their hill. They are puzzled that I am alive, angry that their fantasy of “Sleeping Women” seems to be a hoax. But I know things they don’t. I see my sister stepping out onto St. Charles Avenue, the humidity condensing on her skin even before she begins to run. Three miles is her goal, but somewhere in the junglelike Garden District, she puts a foot wrong and falls into the hole my father fell into in 1972.

Now she stares back at me with vacant eyes, from a canvas as deep as a window into Hell. Having accepted her death in my bones, having mourned and buried her in my mind, this unexpected resurrection triggers a storm of emotions. But somewhere in the chemical chaos of my brain, in the storm’s dark eye, my rational mind continues to work. Whoever painted this picture has knowledge of my sister beyond the moment she vanished from the Garden District. He knows what no one else could: the story of Jane’s last hours, or minutes, or seconds. He heard her last words. He—He …? Why do I assume the painter is a man?

Because he almost certainly is. I have no patience with the Naomi Wolfs of the world, but there’s no denying statistical fact. It is men who commit these obscene crimes: rape; stranger murder; and the pièce de résistance, serial murder. It’s an exclusively male pathology: the hunting, the planning, the obsessively tended rage working itself out in complex rituals of violence. A man hovers like a specter behind these strange paintings, and he has knowledge that I need. He alone in the world can give me what has eluded me for the past year. Peace.

As I stare into my sister’s painted eyes, a wild hope is born in my chest. Jane looks dead in the picture. And the audio tour announcer suggested that all the women in this series are. But there must be some chance, despite my premonition in Sarajevo, that she was merely unconscious while this work was done. Drugged maybe, or playing possum, as my mother called it when we were kids. How long would it take to paint something like this? A few hours? A day? A week?

A particularly loud burst of Chinese snaps the spell of the picture, waking me to the tears growing cold on my cheeks, the hand grasping my shoulder. That hand belongs to one of the bastards who came here today to ogle dead women. I have a wild urge to reach up and snatch the canvas from the wall, to cover my sister’s nakedness from these prying eyes. But if I pull down a painting worth millions of dollars, I will find myself in the custody of the Chinese police—a disagreeable circumstance at best.

I run instead.

I run like hell, and I don’t stop until I reach a dark room filled with documents under glass. It’s ancient Chinese poetry, hand-painted on paper as fragile as moths’ wings. The only light comes from the display cases, and they fluoresce only when I come near. My hands are shaking in the dark, and when I hug myself, I realize the rest of me is shaking too. In the blackness I see my mother, slowly drinking herself to death in Oxford, Mississippi. I see Jane’s husband and children in New Orleans, trying their best to live without her and not doing terribly well at it. I see the FBI agents I met thirteen months ago, sober men with good intentions but no idea how to help.

I shot hundreds of crime scene photos when I was starting my career, but I never quite realized how important a dead body is to a murder investigation. The corpse is ground zero. Without one, investigators face a wall as blank as unexposed film. The painting back in the exhibition room is not Jane’s corpse, but it may be the closest thing anyone will ever find to it. It’s a starting point. With this realization comes another: there are other paintings like Jane’s. According to the audio tour, nineteen. Nineteen naked women posed in images of sleep or death. As far as I know, only eleven women have disappeared from New Orleans. Who are the other eight? Or are there only eleven, with some appearing in more than one painting? And what in God’s name are they doing in Hong Kong, halfway around the world?

Stop! snaps a voice in my head. My father’s voice. Forget your questions! What should you do NOW?

The audio tour said the paintings are sold through a U.S. dealer named Christopher something in New York. Windham? Winwood? Wingate. To be sure, I pull the Walkman off my belt and jam it into my crowded fanny pack. The movement triggers a display case light, and my eyes ache from the quick pupillary contraction. As I slide back into the shadows, the obvious comes clear: if Christopher Wingate is based in New York, that’s where the answers are. Not in this museum. In the curator’s office I will find only suspicious curiosity. I don’t need police for this, especially communist Chinese police. I need the FBI. Specifically, the Investigative Support Unit. But they’re ten thousand miles away. What would the boy geniuses of Behavioral Science want from this place? The paintings, obviously. I can’t take those with me. But the next-best thing is not impossible. In my fanny pack is a small, inexpensive point-and-shoot camera. It’s the photojournalist’s equivalent of a cop’s throwdown gun, the tool you simply can’t be without. The one day you’re sure you won’t need a camera, a world-class tragedy will explode right in front of you.

Move! orders my father’s voice. While they’re still confused.

Retracing my steps to the exhibition room is easy; I simply follow the babble of conversation echoing through the empty halls. The men are still milling around, talking about me, no doubt, the Sleeping Woman who isn’t sleeping and certainly isn’t dead. I feel no fear as I approach them. Somewhere between the document room and this place labeled “Nude Women in Repose,” I shoved my sister into a dark memory hole and became the woman who has covered wars on four continents—my father’s daughter.

With my sudden reappearance, the Chinese draw together in excited knots. A museum guard is questioning two of them, trying to find out what happened. I walk brazenly past him and shoot two pictures of the woman in the bathtub. The flash of the little Canon sets off a blast of irate Chinese. Moving quickly through the room, I shoot two more paintings before the guard gets a hand on my arm. I turn to him and nod as though I understand, then break away toward the painting of Jane. I get off one shot before he blows his whistle for help and locks onto my arm again, this time with both hands.

Sometimes you can b.s. your way out of situations like this. This is not one of those times. If I’m still standing here when Someone In Authority arrives, I’ll never get out of the museum with my film. I double the guard over with a well-placed knee and run like hell for the second time.

The police whistle sounds again, though this time with a faint bleat. I skid to a stop on the waxed floor, backpedal to a fire door, and crash through to the outside, leaving a wake of alarms behind me. For the first time I’m glad for the teeming crowds of Hong Kong; even a roundeye woman can disappear in less than a minute. Three hundred yards from the museum, I hail a taxi and order him not to the Star Ferry, which someone might remember me boarding, but through the tunnel that crosses beneath the harbor.