скачать книгу бесплатно

‘How well did she speak English?’

‘A bit of an accent and a few words the wrong way round, but pretty good really.’

‘Did she tell you her name?’

He pulled his contrite face again. ‘She told me, but I didn’t really get that either. It was something foreign, beginning with an “M”.’

‘Can you describe her?’

He nodded. ‘She was a real smiler. Big high cheeks that puffed out when she grinned. Her face was small but kind of chubby. Not fat or anything. Just …’ He searched for the description. ‘Just nice.’

She sounded Slavic. Or Scandinavian with the blonde hair? ‘Did she say why she was going to Ireland?’

‘To meet up with her boyfriend. I don’t know whether she was talking about an Irish lad, or a boy from her own country who was working over there. She knew that she had to get a ferry to Dublin, and she would be met there.’

A boyfriend. The fit went in. The carrier bag from Hereford with the aftershave and the underpants. Presents for the beloved. The worry was that she would not have left those behind lightly.

‘Not quite the straight-arrow run to Holyhead where you dropped her, was it, Tony?’ I said, smiling to soften the accusation.

He looked hurt. ‘That wasn’t my fault. I even suggested taking her into Newtown to catch a train. It was already dark by then. But she didn’t like that idea.’

‘Too expensive?’

‘I don’t think that was it. She had already asked me if I knew how strict the Immigration people were at the ferry port. I got the impression that she thought there might be too many people asking questions on a train.’

‘The service station was her choice?’ I asked, letting him hear my doubt.

‘Yes. We checked the map. She wanted to stick to the country roads, she said.’

‘You liked her?’ I asked.

The question puzzled him. He looked at me warily, wondering where I was going with this. ‘I liked what I saw of her,’ he answered guardedly.

‘Weren’t you concerned for her? It’s night now. The dead of winter. She’s a stranger, and you’ve left her in the middle of nowhere.’

He bristled. ‘It wasn’t the middle of nowhere. I left her where it was light, and where she could buy stuff if she needed it. I even bought her chocolate. And water. I’ve never bought a bottle of fucking water in my life before. And I went back.’

‘You went back?’

‘Everyone was coming into town at that time of night. I reckoned she wouldn’t be able to get a lift. So I gave her about half an hour to get fed up, and then I went back to see if she wanted somewhere to stay for the night.’ He held up his hands as if anticipating a protest. ‘Just a bed, mind you. I didn’t have any other intentions.’

‘But she turned you down?’

‘No. She wasn’t there. She’d already gone.’

This rocked me. ‘Tell me, Tony, what time would this be?’ I asked very carefully.

He thought about it. His head moving slightly with the enumeration process. ‘About eight o’clock. No later than quarter past. I hung around for a while to make sure that she hadn’t just gone for a bit of a wander.’

It made no sense. Her destiny lay with that minibus one and a half hours later. So where had she disappeared to?

‘Sure you don’t want to have a look?’

I turned round. He was holding the phone up tauntingly, a big grin on his face. I had counted on him not being able to resist it.

I snatched the phone out of his hand.

A split second of jaw-dropped surprise, and then he wailed, ‘You bastard –’ Making a lunge for it.

I held him back with my forearm, the other hand holding the phone up out of his reach.

‘Give that back to me, you fucker!’ He was snarling now, pushing hard, trying to snatch at the phone in my hand. He was straining, twisted out of balance. I dipped the forearm I was using to restrain him, and used my elbow to chop him hard in the groin.

A huge gasp of air fused into a groan and he went slack. For a moment all he could do was stare at me reproachfully, mouth wide open like a betrayed carp.

He shook his head. ‘I should have known better than to trust a fucking cop.’

‘You didn’t trust me,’ I corrected him. ‘You tried using extortion. I gave you my word, and that’s all you need.’ I opened the door and backed out of the cab holding up the phone. ‘I’m impounding this on suspicion that it’s been used to take pornographic images.’

4

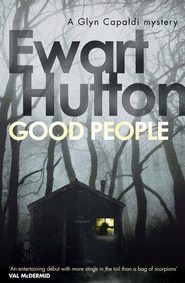

I christened her Magda. I was getting closer. Most likely East European. A student or a migrant worker, probably running in the wrong direction from an expired work permit.

Not a prostitute from Cardiff.

I had been vindicated. I had my own proof that the group had been lying. Now I had to face the scary edge of that triumph. What had really happened in the hut on Saturday night? Where was the girl now?

I spent the next two and a half hours back at the service station watching the CCTV footage in real time. I saw Tony Griffiths walk across the forecourt to buy the chocolate and water. He had been careful, he’d kept his truck out of surveillance range. But I didn’t see Magda. Not until the minibus.

I called Bryn Jones in Carmarthen.

‘Sir, I have uncorroborated evidence that the woman might have been an East European student.’

‘How uncorroborated?’

‘No one is going to speak up.’

‘Can you be any more specific than East European?’ he asked.

‘No, sir, sorry.’

‘Okay, we’ll spread the word informally. See if we have any reports of missing persons that match out there in migrant-worker land.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

I sat in my car and put in enough calls about the other cases I was working on to log that I was still on the planet. Just. I even called the guy in Caernarfon about the Kawasaki quad bike. Now that Tony Griffiths had told me that Magda had been making for the ferry in Holyhead, I wanted to keep an excuse to visit North Wales active.

I leaned back, closed my eyes, and tried to recall the image of the group coming down the hill on that cold Sunday morning. The two brothers in front, the other three staggering behind them.

Who to brace?

I could probably forget the three with partners. The McGuire brothers and Les Tucker. They would now have backtracked with enough explanations and excuses to make them as virtuous as Mother Teresa. Paul Evans, the big one, would either be dumb or belligerent. I didn’t relish tackling either persona.

I called David Williams at The Fleece.

‘Trevor Vaughan, the hill farmer. How do I find him?’ I asked.

I wrote down the directions. As usual I marvelled at how complicated it was trying to find anywhere in the countryside.

‘Anything else you can give me on him?’

‘Quiet. Nice man. Inoffensive.’ He went silent.

‘Am I hearing hesitation?’

‘I don’t like spreading unsubstantiated rumours.’

‘Yes, you do – so give.’

‘There’s talk that he’s done this before. Visited prostitutes.’

‘Am I missing something in Dinas? Is there a local knocking shop?’

He laughed. ‘No, Sandra wouldn’t let me set it up. I’m not talking about Dinas; it’s trips away, to London or Cardiff, rugby games, agricultural shows, stuff like that.’

I thanked him and hung up. So the talk was that Trevor Vaughan wasn’t a virgin. So why did the rest of the group use him and Paul as an excuse for the presence of the girl? Probably to wrap themselves in sanctity, and preserve them from the wrath of their partners. Or was it their intention to test the truth of the rumours?

Some friends.

The road to Trevor Vaughan’s farm followed a small river, which had receded to an alder-lined brook by the time it arrived. The hills were steeper here, the land poorer; sessile oaks, birch, and hazel clumps in the tight dingles, monoculture green pasture on the slopes where the bracken had been defeated, and glimpses of the wilder heather topknot on the open hill above.

A rough, potholed drive led off the road past an empty bungalow and a large new lambing shed to the farmhouse. No dogs barked. An old timber-framed barn formed a courtyard with an unloved, two-storey, whitewashed stone house, raised above the yard. Its slate roof was covered with lichen, and the old-fashioned metal windows were in need of painting.

I’d been around these parts long enough to know not to let the air of neglect fool me. These people could probably have bought a small suburban street in Cardiff outright. They just didn’t waste it on front, or what they regarded as frippery. They saved it for the important things in life: livestock and land.

I parked in the courtyard and got out of the car. Still no dogs. Just the sound of cattle lowing in one of the outbuildings. A woman appeared from around the side of the house wiping her hands on an apron. Small-framed, short grey hair, spectacles, and an expression that didn’t qualify as welcoming.

‘We don’t see representatives without an appointment,’ she announced in a surprisingly firm voice.

‘I’m not a rep,’ I said, opening my warrant card. ‘I’m a policeman – Detective Sergeant Glyn Capaldi. Are you Mrs Vaughan?’

‘Yes.’

‘Is Trevor around?’

She scowled. ‘I thought we were finished with that business. Emrys Hughes told Trevor that it was over.’

I smiled. ‘I just need to ask a couple more questions.’

‘You’ll have to come back another time.’ She inclined her head at the hill behind the house. ‘He’s busy up there with the sheep.’

‘I could go up and see him.’

She gave my car a sceptical appraisal. ‘You won’t get up there in that.’

‘I could walk.’ She looked askance at my shoes. ‘It’s all right, I keep some boots in the car,’ I told her. She sucked in her cheeks, her face tightening into mean little lines as she suppressed her natural inclination to tell me to get off their land. I was glad that she wasn’t my mother.

Following her instructions, I took a diagonal line across the contours, steadily rising towards the open hill, making a point of shutting all the gates behind me. I came to a collapsed stone field shelter with an ash tree growing through the middle of it. According to the woman’s directions I was spot on track.

And I would have kept on going like a naïve and trusting pilgrim, onwards and upwards to the open moor, if a fluke of the wind hadn’t brought the sound of sheep to me. From the wrong direction. I followed the sound to the crest of a rise. The ground dropped into a cwm, and, where it levelled out, I saw a Land Rover in a field beside a pen of sheep. The old crone had deliberately misdirected me.

The dogs were the first to see me traversing down the steep side of the cwm. Two of them. Black-and-white sheepdogs circling out at a scuttling run to flank me, practising dropping to their bellies, preparing to effect optimum ankle damage. The sheep, sensing the dogs on the move, started to make a racket.

Trevor Vaughan, in the pen, looked up from the ewe he was inspecting. He raised his voice and called the dogs in. I waved. He watched me descending for a moment, and then waved back, any welcome in the gesture held in reserve.

He was wearing a grey tweed flat cap, an old waxed jacket worn through at the creases, and green waterproof overtrousers. I had checked, he was twenty-four, but he looked older. A mournful, triangular-shaped face, which, for a man who spent his life outdoors, was remarkably pale.

‘Mr Vaughan,’ I shouted, as I got closer, ‘I’m Detective Sergeant Capaldi.’

‘I know who you are, Sergeant. Emrys Hughes told us.’

The dogs, sensing a distraction, made a move towards me again. He checked them with a series of short whistles, and with a couple of clucks and a gesture he got them on to the open tailgate and into the back of the Land Rover. I was impressed.

‘I have nothing more to say about Saturday night.’

‘I’m not here to ask about that.’

He looked surprised. ‘You aren’t?’

‘No, I want to know where – what’s her name? Magda? – where is she now?’

He wasn’t a good actor. He shook his head and feigned surprise, but he wasn’t used to it. ‘I don’t know anyone called Magda. I don’t know who you’re talking about.’

I gave him a con cop smile. ‘Who decided to call her Miss Danielle?’

‘That’s what she called herself.’

‘You’re lying, Mr Vaughan.’

He didn’t protest. He looked away from me. I thought I had him. And then I heard it too. I followed his line of sight. A late model, grey Land Rover Discovery was coming up the cwm towards us. I stuck myself in front of him. ‘I need to know, Trevor. Has anything happened to that woman?’

He shook his head. Almost imperceptibly. It was aimed at me. As if he didn’t want whoever was driving the Discovery to see that he had communicated.

‘Trevor …’ The yell came out of the open window as the Discovery pulled up. The driver pretended to only then recognize me. ‘What are you doing here?’ his voice registering surprise. Ken McGuire was a better actor than Trevor Vaughan. The old crone had not just misdirected me, she had call in reinforcements.

‘Afternoon, Mr McGuire,’ I said cheerily. I sensed that I had got close to something with Trevor Vaughan, but instinct warned me not to let Ken McGuire suspect it.

He got out of the Discovery playing it puzzled, looking between the both of us. ‘I came over to borrow a raddle harness, Trevor. You’re Sergeant Capaldi, aren’t you? I’ve seen you in The Fleece.’