Полная версия:

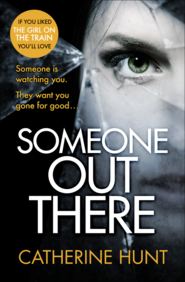

Someone Out There

CATHERINE HUNT

Someone Out There

This is a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Copyright © Catherine Hunt 2015

Catherine Hunt asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780008139667

Version 2015-11-06

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Killer Reads Back Ad

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE

Laura was tired and she was late. Sarah had kept her talking in the office and then, because Sarah needed a shoulder to cry on, she’d gone with her to a wine bar to talk things through. Now it was almost nine o’clock and Laura just wanted to get home. The traffic lights stayed obstinately red. She drummed her fingers impatiently on the steering wheel. Rain lashed down on the windscreen.

A car drew up in the lane beside her. A four-wheel drive with tinted windows. Huge and dark and menacing. A monster. It loomed over her, music pumping – a heavy beat pulsing against her driver’s window, drowning out the rain.

It stopped very close to her, far too close, with its bonnet stuck out aggressively in front. She didn’t look across, kept her eyes straight ahead, but she had the feeling that the driver was staring at her. Another idiot, she thought, who’d seen a woman in a sports car and had decided to show her who was boss.

The lights changed and she didn’t try to race it. She would just sit back and let it burn up its tyres on the wet road.

Laura waited but the monster didn’t move. It sat there with the lights at green. A horn sounded from behind. It still didn’t move, just stayed close beside her, and that was when the alarm bell first began ringing in her head. Not much of one, no big deal, no more than a tinkle really.

She drove off then – fast, using every bit of the 0 to 60 in six-point-five seconds that the Audi TT’s engine had to offer. Off and away, leave all the trouble behind. She liked that thought; it fitted her new philosophy for life. She’d moved on, settled down with Joe, and given up the London rat race.

Out in front, she slowed down, back within the speed limit. She looked out for the four-wheel drive but it was nowhere in sight. Her mind went back to thinking about work and especially about the Pelham divorce case.

Her client, Anna Pelham, had rung that morning to say she’d had two emails threatening to kill her. She’d sent them on to Laura. They were vicious, explicit death threats and Anna was certain her husband had sent them, though they had not come from his email address. There had been other emails sent to Anna from the same address, ranting and blustering, but these were the first to threaten her life. These were in a different league altogether and it was a dangerous escalation.

Laura had reported the death threats to the police and pressed them to charge Harry Pelham with harassment. Anna was being incredibly brave. She refused to be intimidated, sticking to her guns over the divorce. In fact, the threats seemed to have made her more determined than ever to protect her interests and especially those of her eight-year-old daughter, Martha. Good for her. If Harry Pelham had hoped to beat her into submission, his plan had seriously backfired.

When Anna had first instructed Laura to act in the divorce, she had explained how jealous and controlling Harry was. His abuse and rages had got worse and worse and then he had started hitting her. She had not wanted to leave him, had tried to keep the family together, but in the end it got so bad she had no choice. On Easter Day, after he’d slapped her hard in the face and said he’d hated her for the last six years, she walked out of the family home taking Martha with her.

Laura had heard similar stories before in her career as a divorce lawyer and she thought she’d stopped being upset by them, but somehow Anna’s graphic descriptions of what she had endured at the hands of Harry had got under her skin. They brought back all the old memories of her parents’ marriage, memories she had tried to bury.

Driving on autopilot, thinking about what more she could do to help Anna, Laura turned off the main Brighton road and into the lanes that led to home. An empty road ahead, no speed cameras here, she touched the accelerator and the Audi surged forward. She liked to feel its power. She knew the road well; the clear straight runs where she could have fun and the two big bends where she had to take care. Her foot pressed harder on the accelerator, the woods flashed by on either side.

A wild wind was bringing down the autumn leaves. They danced across her windscreen, pinned down now and again by the rain, then whirled away by the speed of her passage.

Laura relaxed and the cares of the day dropped away. She thought of Joe waiting for her and smiled. She would soon be home.

The red tail lights of a car in front were coming up fast and she changed down a gear ready to overtake. There was plenty of time before the bend. No doubt about that. She pulled out.

Lights. Headlights. Full on and heading straight for her, fast. Where the hell—Adrenaline pushed the thought from her brain before she could finish it. Too late to fall back. She was committed. Her foot stamped down on the pedal and she’d never been so glad that she drove a sports car.

The seconds played out in slow motion. The lights dazzling, filling her head, illuminating the channels of rain running down the windscreen, illuminating her white knuckles on the wheel. The ear-splitting, never-ending blast of a horn, sowing madness in her mind. Waiting for the impact, for the smash and crash of tearing metal and flesh.

Then she was past. Intact. Back on the right side of the road. Wide, terrified eyes looking in the mirror. The car she’d overtaken was far behind, dwindling at an alarming rate. It had slowed right down, maybe stopped. But where was the other? The one that had almost killed her. No sign of it at all and that was a scary thing, because the road was straight and it had to be there.

Not as scary as the other thing though. The thing that had the alarm bell in her head ringing out loud this time. She had recognized that car. It was the four-wheel drive again. The monster. And now it had disappeared.

Suddenly the big bend in the road was upon her. In her fear she had forgotten it and she hit it far too fast. Braked too hard, wrenched the wheel too far, the car went out of control. It skidded across the wet road and up onto the bank on the far side. For a moment it teetered, poised to turn over, a toss-up which way gravity would take it. Tails you win, heads you lose. The wheels came back down to earth.

It was the bank that saved her, saved her from the trees she would have ploughed into if the land had been flat. It slowed the car enough for her to wrench back control. Thank God there had been no one coming the other way.

Laura stopped the car, pulling off the road at the entrance to a wide track leading into the woods. Her arms and legs were jelly. She opened the door, swung trembling legs to the ground, and sat, eyes tight shut, sucking in great breaths of the cold, wet air.

The sound of a car made her open her eyes nervously and she watched with a jolt of panic as a drop of something more solid and sticky than rain fell on her skirt. There was another … and another. She touched it; put the finger to her lips. Tasted blood. The mirror showed a bloody gash, above and through her left eyebrow.

Another car passed. She could see the faces of the occupants, a young couple looking out at her curiously as they went by. She felt terribly vulnerable. What was she doing sitting alone and injured by the side of the road in a dark wood? She must get out of here. Suppose someone stopped, suppose the four-wheel drive came back?

She was cross with herself. She didn’t scare easily, she shouldn’t let herself get in a state. She’d had a near miss, that was all; a nasty near miss but it was over now. As for the 4x4, she thought she’d recognized it but how could she be sure? There were dozens of them, all the same, hard to tell one from another. But hadn’t she heard that same music again as it tore past her? That heavy beat pulsing in her skull.

She shook her head to clear it and blood spattered on the dashboard. She was a bit dizzy; she wasn’t sure she should drive.

Call Joe. That was the best idea. Get him to come out and collect her. They could leave her car and pick it up the next day. But she didn’t much like the idea of it being left there overnight. She hesitated.

More cars coming, that decided it. She would call him. She reached for her bag on the passenger seat but it wasn’t there. Saw it, fallen on the floor, and stretched down to pick it up and take out her mobile. The movement made her feel faint. She stopped with her head bent down and waited.

She listened to the noise of an approaching car. There was something wrong with it. It was different but she couldn’t work out why. She left the bag, pulled herself upright and as her eyes came level with the passenger window she saw it. In the wood, lights blazing.

That was why the noise had sounded wrong, she realized. It was coming from the wrong direction, it was charging up the track towards her. It was the 4x4.

There was a locked barrier across the track, about thirty feet into the wood from where she was parked. It stopped access for the general public but allowed in forestry vehicles whose drivers had the key. Surely it would stop the monster.

Something told her not to bet on it. Not to wait and see. She knew she had to move. But she sat for vital seconds, fascinated, unable to drag her eyes away from the oncoming lights. No wonder, she thought, that rabbits froze, transfixed in the road, waiting to be run down. With an effort she slammed shut the driver’s door, yanked on the seat belt and started the engine.

It was perilously close to her now but still she hesitated. Vaguely her mind registered that this must be how it had appeared and disappeared so suddenly – by using the woodland tracks. It came to a slight rise in the ground, and as Laura watched, appeared to rear up before her, a huge, malevolent metal beast, eyes piercing and engine roaring. She jammed in first gear and fled, tyres shrieking. Behind her, the barrier disintegrated.

The feeling of faintness had gone, swept away by fear. Her head was clear of everything except the need to get away. She was only seconds ahead, had moved only just in time. She looked in the mirror, saw her pursuer turning out of the wood and onto the road.

There was no doubt any more that it was pursuing her. Who was the driver and what did they want? A small part of her brain told her to observe. Read the licence plate, identify the make of car, pin down the details. Gather the clues to the who and the why. Vital for later, but worthless now. The rest of her brain cared only for safety. It told her to run and run, find sanctuary, nothing else mattered. The chase was on – she was the wildebeest, injured and fleeing for its life.

Sanctuary. Where was sanctuary? On a dark night, an empty road, still eight miles from home.

It was gaining on her. She knew these roads, she was driving a fast car, but it was gaining on her, for God’s sake. Headlights – on full beam, blinding her – filling the car, filling her head. Drive faster, panic yelled in her head, but she took no notice. She knew that if she did, she was going to crash, she was a dead woman.

Sanctuary was other people. She had to reach them. They would make her safe. It could not pursue her then. But she daren’t try to find her mobile; it was in the bag on the floor and she needed all her concentration for the road. In any case, no one could get to her in time.

There was no time. It was right behind, pushing, intimidating, inches from the rear bumper. She heard the music blasting, saw the monster looming over her. Jesus, it was going to hit her!

She tensed for the blow, but it didn’t fall. A car was coming in the opposite direction. The 4x4 backed off a fraction. She started pumping the horn, flashing her lights, hoping for help. It did no good. The car came and went, its driver probably delighted to give them both a wide berth.

The monster surged back and she felt a sudden dread. Oh yes, she thought, I know what you’re going to do. You’re going to overtake, jam on your brakes and force me to stop.

Faster. Go faster. Panic was shouting to her again, screaming at her to run. The Audi could beat off the 4x4 with no trouble. Race away, top speed, before it’s too late, but self-preservation stopped her. She wasn’t ready to die yet.

There was a turn-off not far ahead, she remembered. A narrow road; little more than a lane. She might be safer there, less room for her pursuer to manoeuvre, more chance for her to persuade an oncoming car to stop. Or maybe not. Maybe a narrow lane would be a trap. Should she take it? She couldn’t decide. Her brain felt hot and choked.

The lights behind moved and the engine revved. It was coming out, it was overtaking. Her decision was made.

It was level with her now and she forced herself to look. Observe. Log the evidence. She was a lawyer and lawyers were supposed to be good at that. But there was nothing to see. Desperately, she stared into the night but there was just the rain on the tinted windows and darkness beyond. Impenetrable.

It stayed put. Not passing by, just staying level, getting closer and closer to her. Dear God, she thought, it’s going to run me off the road!

Where was the turning? She should have reached it by now. Please let it be there, she prayed. And then she was on it, almost missing it. She wrenched the wheel violently to the left, so sharply that for a moment she didn’t think she would make it. She felt the back of the car skid on the wet tarmac, collide with the side of the four-wheel drive before peeling off alone into the lane. She changed down into second, brought the car under control, and slammed her foot to the floor.

Nothing in the rear-view mirror. Her pursuer was gone. A wave of euphoria buzzed through her, ridiculous, of course, because it couldn’t be long before it was back. But for the moment that didn’t matter. She had shaken it off, if only briefly, and that was just great. Tears of relief filled her eyes. Hell, she thought, now I can’t even see where I’m going. She wiped away the tears and felt the side of her face sticky with blood.

No sign of it. She couldn’t believe it. Kept looking in the mirror but it stayed clear. She thought that time was playing tricks – that what seemed to her, in her terror, like an eternity, when the 4x4 could have turned round and caught up with her three times over, was in reality just a few seconds and it might only now be turning into the lane after her. She stared at the clock on the dashboard and when another whole minute had gone by, she really started to hope. Another turning in the road. She took it. Took every turning she came to, kept driving fast, with no idea or care about where she was going, but each one making her feel a little bit safer, twisting and turning away from danger.

She felt like she was driving round in circles, her heart stopped by every passing car, her eyes strained for lights in the woods as she imagined it chasing her across country, her brain punch-drunk, unable to focus on finding the route home. It was almost ten minutes later that she made it out of the lanes onto a main road she recognized, and joined a welcome convoy of traffic.

Reaction set in seriously then. Her arms were shaking, her teeth were chattering and it was with tremendous relief that she saw the service station. She pulled in, parked by the café and tottered inside.

The man behind the counter looked worried and when she caught sight of her bleeding, tear-streaked face in the mirror, she could understand why. He wanted to call an ambulance but she told him she hadn’t been physically assaulted and she wasn’t drunk or drugged and he settled for her phoning her husband and handed over what she needed most – a strong black coffee.

She sat huddled over it, trying to remember. But there was nothing, nothing she could recall but the dark and the fear and the noise. No make, no model, no part of a licence plate that could be dredged from her subconscious. No clue as to who the driver had been. Not a single fact to tell the police. And she knew the police – without facts and details and evidence, she was wasting her time.

The door opened and she looked up. Joe. How fast he’d arrived, a white knight charging to her rescue in record time. Her battered heart gave a thump of joy. Tall and solid and hugely comforting. Things would be all right now, she thought.

CHAPTER TWO

It was 4 a.m. and Harry Pelham lay awake thinking about the poisonous, scheming bitch who was doing her best to hang him out to dry. He smiled bitterly to himself. No, he wasn’t thinking about his wife, though she also fitted the description; he was thinking about her lawyer, Laura Maxwell.

She had been responsible for the nineteen-page divorce submission designed to crucify him. It damned him as a bully, a wife beater, and a bad father. He could remember every word of those nineteen pages. They sent him into a frenzy of rage and resentment. It was a vile, disgusting diatribe, full of lies and exaggerations. It had lodged in his brain like splinters of glass.

His wife had no doubt provided the raw material but she’d been egged on by the toxic Maxwell woman; she wouldn’t have done it by herself. The weaving together of that deadly, distorted whole, calculated to tick every box against him, had been the lawyer’s work. He was sure of it and he hated Laura Maxwell for it.

His own solicitor, Ronnie Seymour, usually so shrewd, had been like a lamb to the slaughter. He played through in his head the previous day’s conversation with Ronnie.

‘Slight problem, Harry,’ Ronnie had said on the phone, ‘nothing to worry about, though. Come over and we’ll talk it through.’

How many times in the last few months had he heard those words ‘nothing to worry about’ from Ronnie Seymour. Inevitably, they meant the opposite.

Ronnie had been his good friend and trusted adviser for more than twenty years. He had sorted out, with no trouble at all, the frequent problems that Harry had run into with his property development empire. When Harry had gone too far, had bent the rules, had tried rather too aggressively to ‘persuade’ people who stood in his way, Ronnie had been there to smooth out the consequences. Like a few months ago, when old Charlie Rhodes refused to sell part of his back garden, a crucial piece of land that Harry needed for one of his developments.

Late one evening, Harry knocked on the old man’s door with a higher offer. Charlie yelled at him to piss off, called him a piece of shit and Harry lost his temper, pinning the pensioner against the wall by his throat and telling him how much better for him it would be to take the offer. It turned out that Charlie’s son was a police officer, and shortly afterwards, the police arrived at Harry’s office to question him about the ‘bullying and harassment’ of Charlie Rhodes. It was only because of Ronnie’s efforts that Harry avoided being charged.