Полная версия:

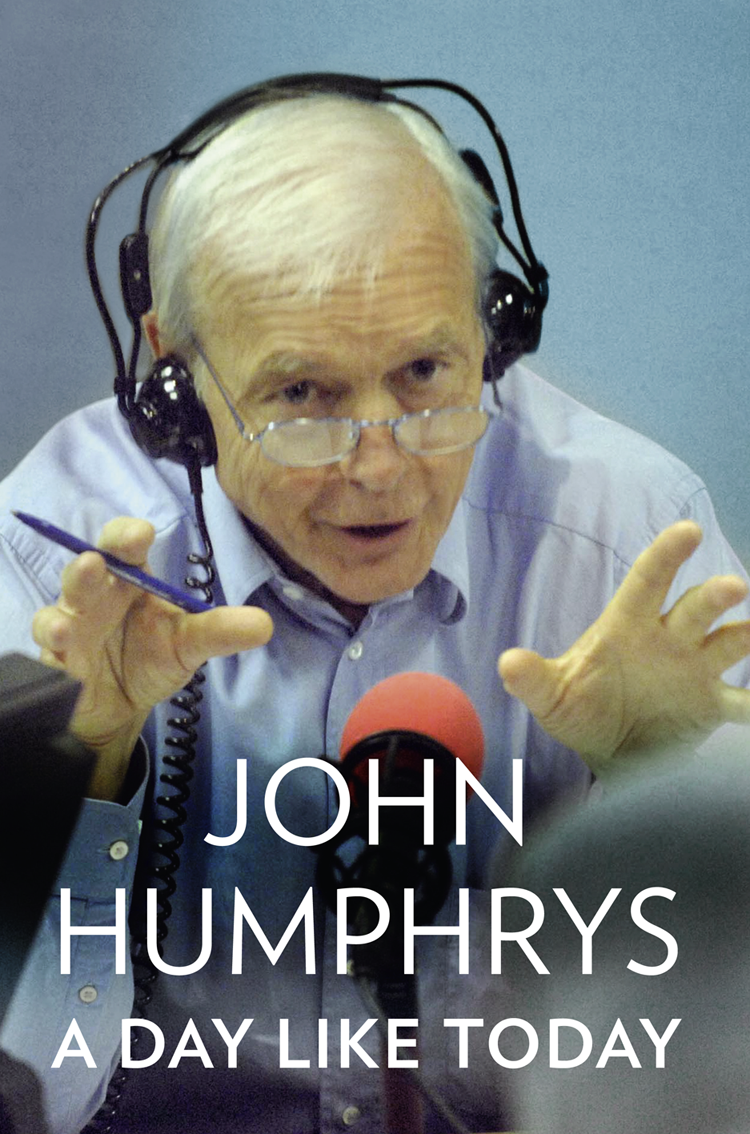

A Day Like Today: Memoirs

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © John Humphrys 2019

Cover image © Jeff Overs/Getty Images

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise stated.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

John Humphrys asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007415571

eBook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780007415601

Version: 2019-09-13

Dedication

For Sarah

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 Prologue

7 Part 1 – Yesterday and Today

8 1 A childhood of smells

9 2 The teenAGE pAGE

10 3 Building a cathedral

11 4 A gold-plated, diamond-encrusted tip-off

12 5 A sub-machine gun on expenses

13 6 A job that requires no talent

14 Part 2 – Today and Today

15 7 A very strange time to be at work

16 8 Why do you interrupt so much?

17 9 ‘Come on, unleash hell!’

18 10 A pretty straight sort of guy?

19 11 Management are deeply unimpressed

20 12 Hamstrung by a fundamental niceness

21 13 A meeting with ‘C’

22 14 The director general: my part in his downfall

23 15 Turn me into a religious Jew!

24 Part 3 – Today and Tomorrow

25 16 The political deal

26 17 Shrivelled clickbait droppings

27 18 Goodbye to all that

28 Picture Section

29 Also by John Humphrys

30 About the Author

31 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivv1234579101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111113115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313315317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367368369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383384385386387388389390391392393394395396397ii

Prologue

In which I answer the questions in the way I choose …

JH: Good morning. It’s ten past eight and I’m John Humphrys. With me live in the studio is … John Humphrys. It’s just been announced that he’s finally decided to leave Today after thirty-three years. Mr Humphrys, why leave it so long?

JH: Well, as you said it’s been thirty-three years and that’s—

JH: I know how long it’s been … far too long for the taste of many listeners, some might say. It’s because your style of interviewing has long passed its sell-by date, isn’t it?

JH: Well I suppose some people might say that but—

JH: You suppose some people might say that? Is it true or not?

JH: I’m not sure it’s really up to me to pass judgement on that because—

JH: What d’you mean you’re ‘not sure’! You either have a view on it or you don’t.

JH: Well I do but you keep interrupting me and—

JH: Ha! I keep interrupting you! That’s a bit rich. Isn’t that exactly what you’ve been doing to your guests on this programme for the past thirty-three years and isn’t that one of the reasons why the audience has finally had enough of you … not to mention your own bosses?

JH: I really don’t think that’s fair. After all it was only politicians I ever interrupted and only then if they weren’t answering the question.

JH: You mean if they didn’t answer YOUR questions in the way YOU chose—

JH: Again that’s not fair because—

JH: Are you seriously suggesting that you didn’t approach every political interview with your own views and if the politician didn’t happen to share those views they were toast? You did your best to cut them off at the knees.

JH: That’s nonsense. The job of the interviewer is to act as devil’s advocate … to test the politician’s argument and—

JH: And to make them look like fools and to make you look clever. It’s just an ego trip, isn’t it?

JH: No … and if that were really the case the politician would refuse to appear on Today. And mostly they don’t—

JH: Ah! You say ‘mostly’, which is a weasel word if ever I heard one. Isn’t it the case that when they do refuse it’s because they know you will deny them the chance to get their message across because all you want is a shouting match?

JH: Not at all. They’re a pretty robust bunch and I’d like to think they hide from the live microphone because they don’t want to be faced with questions that might very well embarrass them if they answer frankly and honestly.

JH: I’m sure that’s what you’d like to think but the facts suggest otherwise don’t they? And when they do try to answer frankly, you either snort with disbelief or try to ridicule them.

JH: Look, I wouldn’t deny that I get frustrated when the politician is simply refusing to answer the question, and I’m sure the listeners feel the same. It’s my job to ask the questions they want answered and if the politician refuses to engage or pulls the ‘I think what people really want to know …’ trick, then it’s true that occasionally I do let my irritation show.

JH: Nonsense! The fact is you have often been downright rude and that is simply not acceptable.

JH: Well … we agree on something at last! You’re absolutely right when you say being rude is unacceptable and I admit that I’ve been guilty of it – but not often. In my own defence I can think of only a tiny number of occasions when it’s happened and I regret it enormously – not least because it really does upset the audience. One of the biggest postbags I’ve ever had (in the days before email which shows you how long ago it happened) was for an interview in which I really did lose my temper. The audience ripped me apart afterwards and they were quite right to do so. If we invite people onto the programme we have to treat them in a civilised manner.

JH: So we’ve established that you’re not some saintly figure who always occupies the moral high ground. I suppose that’s a concession of sorts. But what I’m accusing you of goes much wider than that. Of course you have a responsibility to the audience and to the interviewee but you also have a wider responsibility. Let me suggest that when people like you treat politicians with contempt you invite us, the listeners, to do the same. And that’s bad for the whole democratic process.

JH: Once again, I agree with you. Not that we treat them with contempt, but that programmes like Today might contribute to the growing cynicism society has for politicians and the whole political process. But which would you prefer: a society in which politicians are regarded with awe and deference, or a society in which they are publicly held to account for their actions by people like me who question them when things go wrong or when we suspect they might be misleading us?

JH: Not for me to say: I’m the one who’s asking the questions this time remember! But what I’m asking you to deal with is a rather different accusation. If people like you, who’ve never been elected to so much as a seat on the local parish council, don’t show any respect to the people the nation has elected to run the country … why should anyone else?

JH: But that’s not what I’m saying. Quite the opposite. I can’t speak for my colleagues, but I have huge respect for the men and women who choose to go into politics. I hate the idea that for so many people politics has become a dirty word. Henry Kissinger once said ninety per cent of politicians give the other ten per cent a bad reputation. The wonderful American comedian Lily Tomlin put it like this: ‘Ninety-eight per cent of the adults in this country are decent, hard-working, honest Americans. It’s the other lousy two per cent who get all the publicity. But then – we elected them.’ Yes, that’s funny, but it’s wrong. One of the greatest broadcasters of the last century, Edward R. Murrow, got closer to it when he chastised politicians who complained that broadcasters had turned politics into a circus. He said the circus was already there and all the broadcasters had done was show the people that not all the performers were well trained.

JH: In other words you regard political interviewing as a branch of showbiz rather than your high-flown pretension to be serving democracy!

JH: Look, I’m not going to pretend that we don’t want our listeners to keep listening and if that means we want to make the interviews entertaining as well as informative I’m not going to apologise for that. After all, the BBC’s founder Lord Reith said nearly a century ago that its purpose was to ‘inform, educate and entertain’. But you’ll note that he made ‘entertain’ the last in that list. Ask yourself: what’s the point of doing long, worthy and boring interviews if nobody is listening?

JH: Ah … so now we get to the nub of it don’t we? It’s all about ratings!

JH: Of course it’s not ‘all about ratings’ but obviously they matter …

JH: … because the higher they are the more you can get away with charging the BBC a king’s ransom to present the programme!

JH: Ah … I wondered how long it would take you to get onto this because—

JH: I trust you’re not going to deny that you’ve been paid outrageous sums of money over the years for sitting in a comfy studio asking a few questions when somebody else has probably briefed you up to the eyeballs anyway?

JH: That’s not entirely fair is it? You know perfectly well I spent years as a reporter and foreign correspondent in some very dangerous parts of the world. And anyway are you really saying the amount a presenter gets paid shouldn’t be related to the size of his or her audience? That’s rubbish!

JH: Ooh … touchy aren’t we when it comes to your own greed! Have you forgotten it’s the licence payer who foots the bill and the vast majority of them earn a tiny percentage of what you take home?

JH: Yes, I am a bit touchy on this subject and that’s partly because for various reasons I got a bit of a bum rap when BBC salaries were first disclosed back in the summer of 2017. And anyway I volunteered several pay cuts as you well know …

JH: Yes yes yes … we all know you’re a saint but I’m afraid we’ve run out of time. John Humphrys … thank you.

JH: And thank you too. And now I’m going to tell my own story without all those impertinent questions …

PART 1

1

A childhood of smells

By the time I joined Today in 1987 I had been a journalist of one sort or another for thirty years and I’d been exposed to pretty much everything our trade had to offer. I had been a magazine editor at the age of fourteen – though whether the (free) Trinity Youth Club Monthly Journal with its circulation reaching into the dozens properly qualifies as a magazine is, I’d be the first to admit, debatable. I’d had the most menial job a tiny local weekly newspaper could throw at a pimply fifteen-year-old – and that’s not just the bottom rung of the ladder: it’s subterranean.

At the other end of the scale I had written the main comment column for the Sunday Times, the biggest-selling ‘quality’ newspaper in the land, for nearly five years. I’d had the glamour of reporting from all over the world as a BBC foreign correspondent – not that it seems very glamorous when you’re actually doing it. I’d had the even greater (perceived) glamour of being the newsreader on the BBC’s most prestigious television news programme.

And I had reported on many of the biggest stories in the world: from wars to earthquakes to famines. I’d seen the president of the United States forced out of office and the ultimate collapse of apartheid. I’d seen the birth of new nations and the destruction of old ones. So on the face of it I had done it all. But, of course, none of it properly equipped me for the biggest challenge in broadcast journalism: the Today programme.

Presenting a live radio news programme for three hours a day, day in and day out, is bound to test any journalist’s basic skills, not to mention their stamina. You need to know enough about what’s going on in the world to write decent links and ask sensible questions. You need enough confidence to be able to deal with unexpected crises.

You need the stamina to get up in the middle of the night and be at your best when people doing normal jobs are just finishing their breakfast and wondering what the day holds in store. And you need to be able to do all that with the minimum of preparation. Sometimes no preparation at all.

But thirty-odd years of trying to do it tells me you need something else. You need to know who you are and what you can offer to a vast audience that’s better than – or at least different from – your many rivals. My problem when I started was that I had no idea what I was offering. I had done so many different things I wasn’t at all sure who or what I was.

Was I a reporter?

I’d like to think so. Reporting is, by a mile, the most important job in journalism. Without detached and honest reporting there is no news – just gossip. At the heart of any democracy is access to information. If people don’t know what is happening they cannot reach an informed decision. I like to think I did the job well enough. I had plenty of lucky breaks and even won a few awards. But I was never as brave as John Simpson or as dedicated as Martin Bell and I never had the writing skills of a James Cameron or Ann Leslie. I did not consider myself a great reporter and knew I never would be.

Was I a commentator?

Positively not. Columnists may not be as important as reporters, but they matter. The best not only offer the reader their own well-informed views on what is happening in the world, they cause them to question their own assumptions. They make the reader think in a different way. I very much doubt that I managed that.

Was I a newsreader?

Well, again, I was perfectly capable of sitting in front of a television camera and reading from an autocue without making too many mistakes. Not, you would accept, journalism’s equivalent of scaling Everest without oxygen. Whether I had the gravitas to command the attention and respect of the audience is another matter altogether. Probably the greatest news anchorman in the history of television news was Walter Cronkite, who presented the CBS Evening News in the United States for nineteen years when it was at its peak in the 1960s and 70s. Cronkite not only had enormous presence and authority, he had a relationship with the viewers that any broadcaster would kill for. It can be summed up in one word. Trust. He was named in one opinion poll after another as the most trusted man in America. He also happened to be a deeply modest and decent man.

As for me, back in 1987, I was just a here-today-gone-tomorrow newsreader who was about to become a presenter of the Today programme and who had not the first idea what he had to offer its enormous audience. I tried asking various editors who had worked over the years with some of the great presenters what I needed to do to make my mark or, at the very least, survive. Most of them gave me pretty much the same answer: be yourself.

As advice goes, that was about as much use as telling me to write a great novel or run a four-minute mile. How can you ‘be yourself’ if you don’t know who or what you are? How can you impose your personality on the programme if you’re not quite sure what it is? It’s not as if you can pop out and buy one off the peg.

‘Good morning, I’m looking for a radio personality.’

‘Certainly sir, anything specific in mind?’

‘Well, it’s for Radio 4 so nothing too flash. Obviously I need to be trusted by the listeners and I suppose it would help if they liked me.’

‘Of course sir, wouldn’t want them gagging on their cornflakes every time they heard your voice would we? But when you say “liked” do you have anyone in mind? Dear old Terry Wogan maybe? Or a bit more on the cutting edge, if I may be so bold? Perhaps a touch of the Chris Evans? It’s always a little tricky designing a personality if the customer doesn’t have a specific style in mind.’

‘Yes, I can see that. How about the trust factor then?’

‘Just as tricky as likeability in a way, sir. Takes rather a long time to earn trust.’

‘Of course … So what about “authority”?’

‘Sorry to be so negative sir, but that doesn’t come easy either. Bit like trust in a way … takes time and depends on your track record.’

‘Hmm … I think what you’re telling me is that you don’t actually have anything in stock that would give me a Today programme personality eh?’

‘I’m afraid so. Perhaps I could offer sir a suggestion?’

‘Please!’

‘Why not stick with what you’ve got and then pop back in … shall we say … five years or so and we’ll see whether it needs a little adjustment?’

‘Thank you … most kind of you.’

‘Not at all sir … is fifty guineas acceptable …?’

Had such a shop existed in the real world I might very well have popped back – not after five years but more likely after a week. Because I learned something very quickly, and it’s this: a curious thing happens when you present a live radio programme such as Today for several hours on end, mostly without a script or without any questions written down. You discover that you have no choice but to ‘be yourself’. There is so much pressure that there is no time to adopt somebody else’s persona or even to think about creating a new one for yourself. And that can be a blessing and a curse. In my case it is both.

Those of us who practise daily journalism need to be able to write to a deadline. You either master that skill or you find another way of making a living, and I can make the proud boast that I have never missed a deadline. Very impressive, you might say, given how long I’ve been practising this trade and how many deadlines I have faced. You might be rather less impressed if I reproduced here some of the rubbish I have written over the years as the clock ticks down – but that’s another matter altogether. The rule is: never mind the quality … get it done and get it done NOW!

I’ve lost track of the number of times the 8.10 story on Today has suddenly changed and another story has taken its place, meaning that I’ve had only three or four minutes to write the introduction. In the pre-computer days it meant hammering away at the typewriter in the newsroom, ripping it out of the rollers as the clock ticked down and then running like hell into the studio with it. That, by the way, is always a mistake. I learned the hard way that you might save five seconds if you run to the studio, but when you drop into your seat in front of the microphone you will be unable to speak for the next thirty seconds because you are out of breath. And you will sound very silly.

I like to think I had a pretty rigid routine when I was presenting Today. I would skim the newspapers in the back of the car that picked me up at about 3.45 a.m. so that by the time we got to New Broadcasting House I had a rough idea of what was going on in the world. Then I would log on to my computer, heap praise on the overnight editor for the invariably wonderful programme he had put together (or not as the case may be) and would set about writing my introductions – or ‘cues’ as we call them. Then I had my breakfast sitting at my desk – a bowl of uncooked porridge oats, banana and yoghurt – while I started to think of the questions I’d be asking my interviewees over the next three hours. So by the time I got into the studio, I had lots of questions written down just waiting to be asked.

In my dreams.

Look, I KNOW it made sense to do just that. I KNOW I should have done what most of my colleagues did, which was read the briefs that had been so painstakingly prepared by the producers the day before and had the structure of the interview written down with some questions just in case the brain went blank at a crucial moment. Something which, I promise you, happened more often than you might think. So why didn’t I do it? God knows. I always ended up finding another dozen things to do that seemed infinitely more important at the time but never were.

It meant that at some point in the programme I would realise that I hadn’t the first idea what vitally important subject it was that I was meant to be addressing with the rather anxious person who had just been brought into the studio. Every morning I promised myself I would be more disciplined in future and every morning I failed. I tried to justify my idiotic behaviour by telling myself that interviews are better if you have no questions written down. After all, we wanted our audience to feel they are listening to a spontaneous conversation rather than to some automaton reading from a list of prepared questions. But there was a balance to be struck and I invariably erred on the side of telling myself it would be alright on the night – even when there was a tiny warning light flashing in my brain telling me I might be about to make a fool of myself.