Полная версия:

Under Pressure: Life on a Submarine

Copyright

Names of Royal Navy personnel have been changed to protect privacy.

Mudlark

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by Mudlark 2019

FIRST EDITION

Text © Richard Humphreys 2019

Illustrations © Tom Hughes 2019

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers

Cover illustration © Neil Gower

Photographs courtesy of the author except where indicated

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Richard Humphreys asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

www.harpercollins.co.uk/green

Source ISBN: 9780008313050

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008313081

Version: 2019-09-03

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008313050

Dedication

For my father, who loved life

V.J.C.H.

1928–2016

Epigraph

‘Submariners themselves were regarded as not quite the thing – smelt a bit, behaved not too well, drank too much. They were regarded as a sort of dirty habit in tins.’

Admiral Sir John Forster ‘Sandy’ Woodward, One Hundred Days, 1992

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Note to Readers

5 Dedication

6 Epigraph

7 Contents

8 Author’s Note

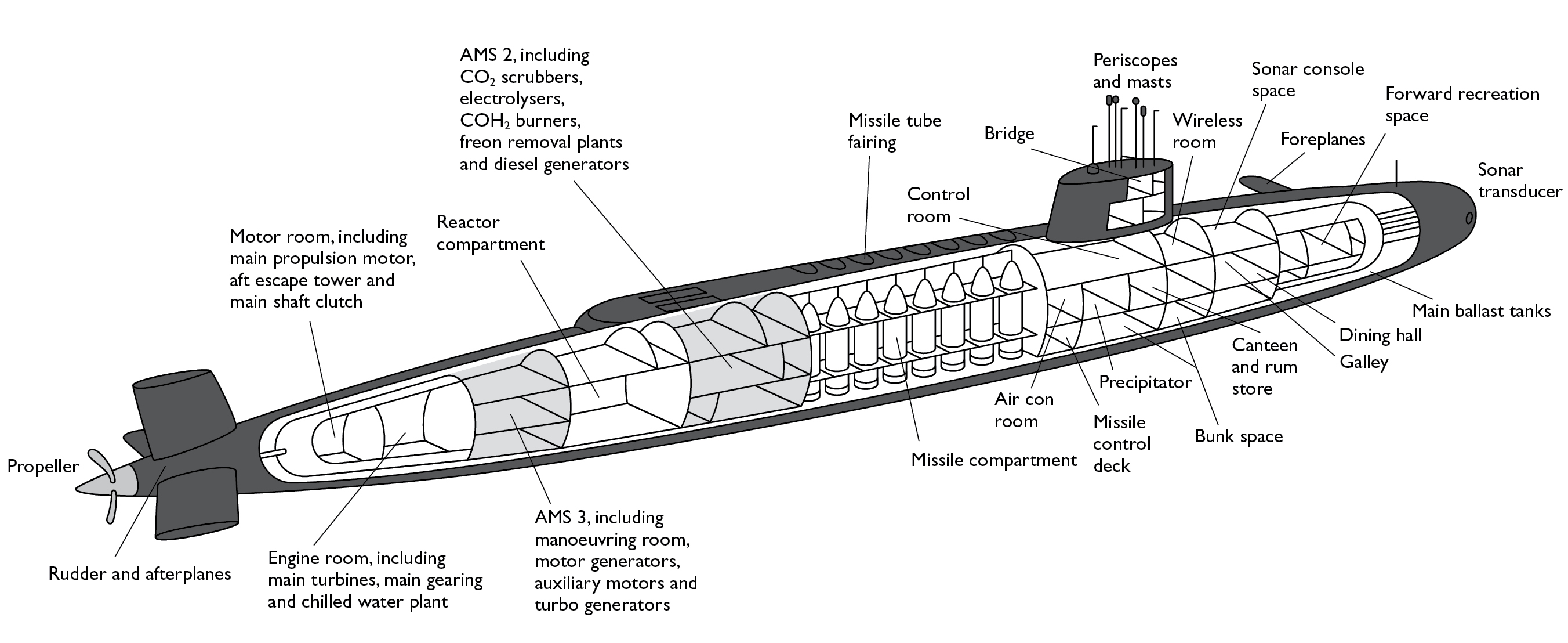

9 Diagram of Polaris Submarine

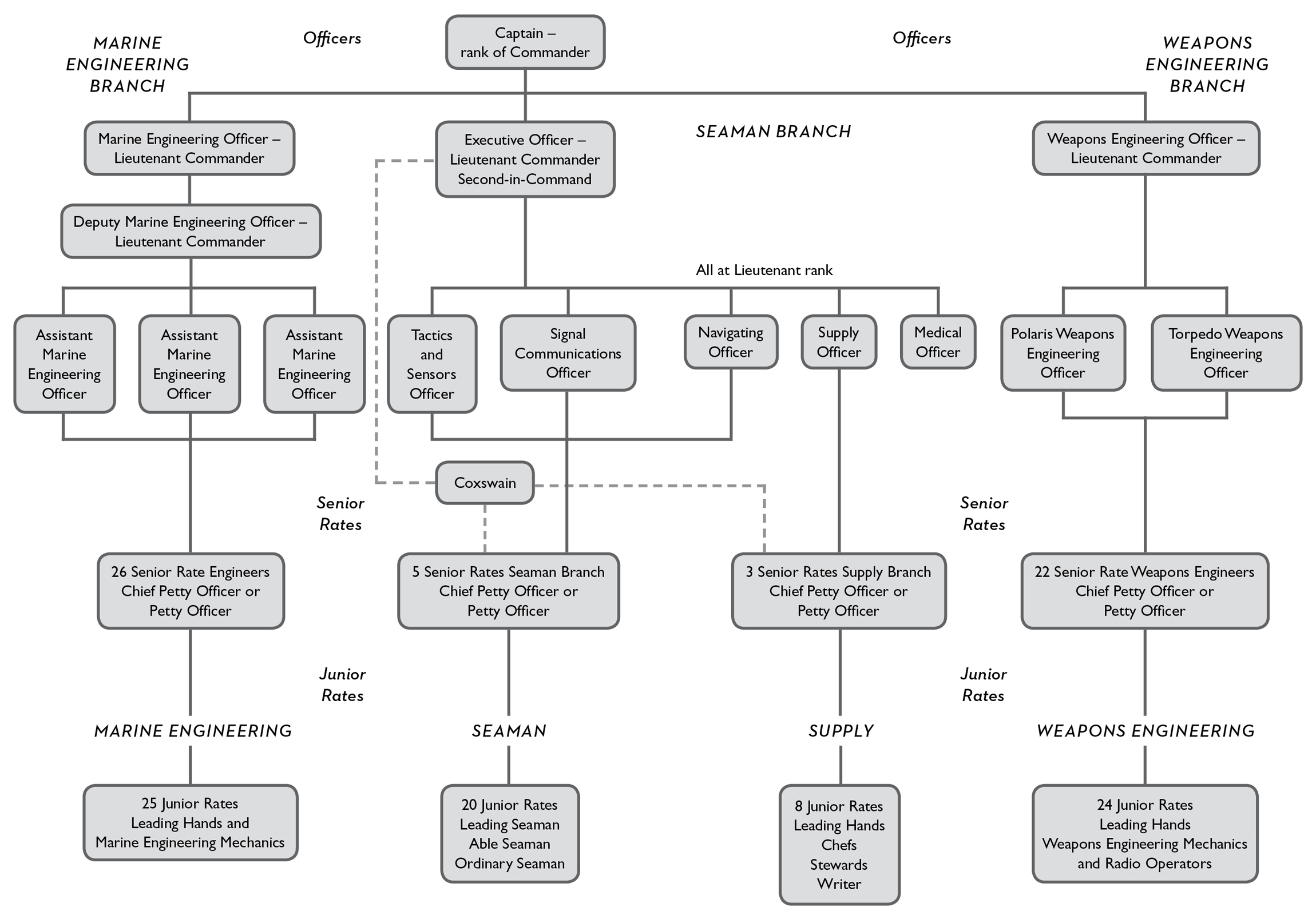

10 Polaris Submarine Hierarchy

11 Glossary

12 Introduction

13 1 Beasting

14 2 HMS Neptune, Faslane

15 3 The Bomber

16 4 Alongside

17 5 Work-up

18 6 Coulport

19 7 Before the Off

20 8 Set Sail

21 9 The Dive

22 10 A Brief Tour

23 11 No Time

24 12 All the Time in the World

25 13 Downtime

26 14 Booze

27 15 Snadgens

28 16 Porn

29 17 Familygrams

30 18 Showtime

31 19 Under the Lights

32 20 Cut Off

33 21 Racked Out

34 22 Food, Glorious Food

35 23 The Day Job, the Night Job, Repeat

36 24 Letters from the Grave

37 25 Captain Is God

38 26 To Launch or Not to Launch

39 27 Homeward Bound

40 28 Off Crew

41 Acknowledgements

42 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiiiiv1234691011121314151617181920212223242526272829313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298

Author’s Note

I switched off the radio, made my way slowly up the stairs, shut the bathroom door and shed a tear. It was 16 November 2017, the day after the Argentinian submarine the ARA San Juan went missing in the South Atlantic off the coast of Argentina. At first, in those early days, it was unclear what had provoked the accident or what fate had befallen the crew, whether they might somehow still be alive beneath the waves. But then, with time, the cause of the tragedy became clear. An electrical malfunction had short-circuited the battery, which led to a complete loss of power for the old diesel-powered submarine. The San Juan had then sunk to the ocean depths, before finally imploding under the intense water pressure. The entire crew of 44, which included the first female submarine officer in the Argentine Navy, Eliana Krawczyk, had perished.

On hearing of the crew’s horrible fate, my thoughts switched back to my own period of service aboard a submarine and how blessed I’d been not to have suffered a similar fate. There are innumerable fine lines between life and death when operating in one of the most testing environments the world has to offer, where one wrong move can almost instantly bring chaos and disaster. After the San Juan tragedy, friends who had previously never seemed the slightest bit interested in my naval career started pumping me vigorously with questions about submarines, the dangers involved in underwater living, and exactly how I retained my sanity during the long weeks and months away at sea, cut off from the rest of the world. This book is a direct result of those conversations.

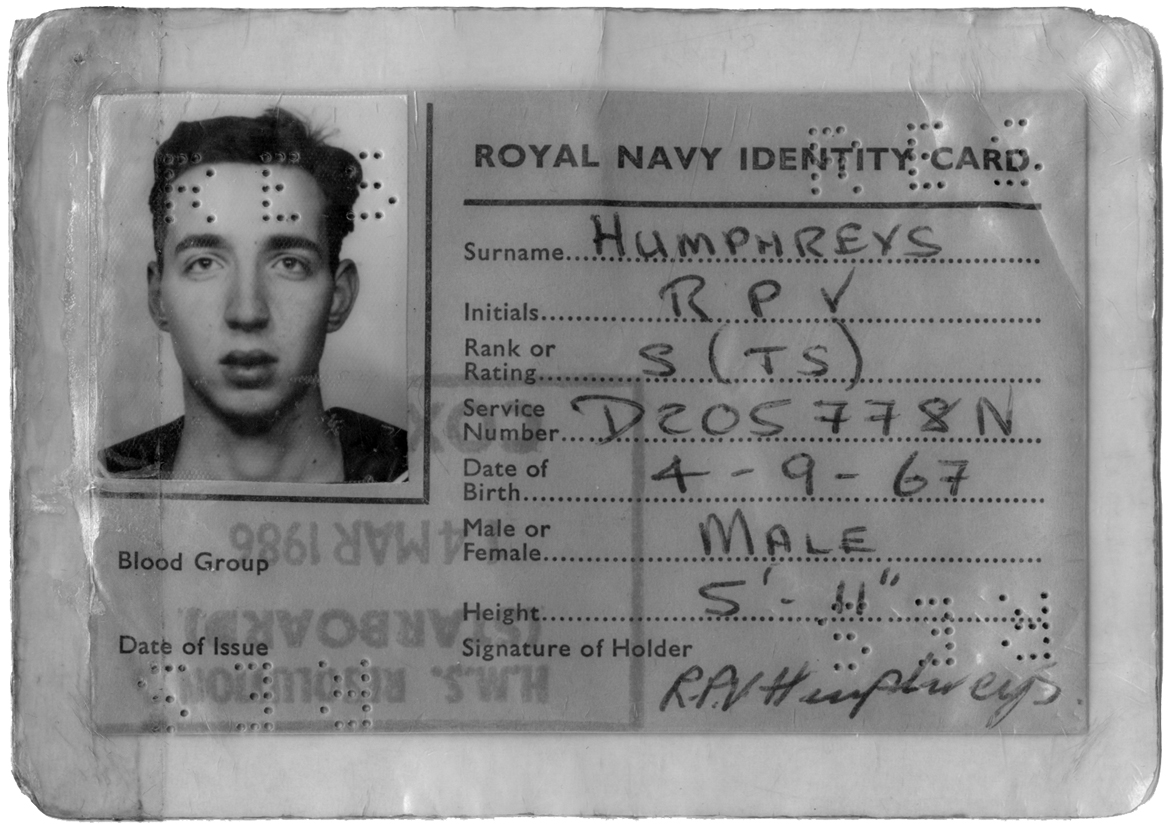

At the age of 18, in the mid-1980s, I became a member of an elite group who served aboard Britain’s nuclear deterrent, continuing my service for the following five years, while the Cold War was still hot and nuclear confrontation seemed scarily imaginable. In the 30 years since I left the Navy, submarine living and operating have remained fundamentally the same, although the creature comforts – including email, laptops, PlayStations and other products of the digital age – mean that some aspects are possibly easier now than they were during our stand-off with the Soviet Union.

I hope that what you are about to read will go a little way towards explaining the raw, real-life experience of what it’s like to spend prolonged periods of time on a submarine. I’ve tried not to focus on the military aspects, although by necessity some of these will come into the story, but have rather concentrated on how it feels to live day-to-day in this claustrophobic, man-made environment, describing the pressures it exerts on both one’s mind and body.

This is a book about life lived at the extremes, and there are few more extreme situations than living underwater in what is effectively a giant, elongated – if beautifully streamlined – steel tin can. I hope that it informs, shocks, excites and entertains, and that it moves you, the reader, to spare a thought for the brave men and women who at any given moment are patrolling the world’s waters, keeping their silent vigils.

The ID card issued to me on joining HMS Resolution. I’m going for a Mick Jones from the Clash vibe.

Diagram of Polaris Submarine

Polaris Submarine Hierarchy

Glossary

Terminology

alongside: status of submarine when berthed at jetty, in Resolution’s case at Faslane, awaiting to go to sea for patrol or work-up. Also where ship maintenance, storing ship, and loading both missiles and torpedoes – at Coulport – take place.

AMS (auxiliary machinery space): three areas on the submarine – AMS 1, 2 and 3 – where various bits of machinery are located.

angles and dangles: deep-water procedure where submarine dives and heads back to surface at steep inclines to test if boat is safely stowed for sea. Any noise generated by falling pots, pans or bits of machinery could give boat’s position away on patrol. Great fun.

ARL (Admiralty Research Laboratory) table: located aft and on starboard side of control room. Mostly used when surfaced. Map lies on top of it and periscope navigational fixes taken from landmarks are applied to chart to calculate submarine’s position in conjunction with SINS.

attack team: warfare team under guidance of XO reporting to captain, who has overall command. Consists of sonar team, tactical systems team, warfare seaman officers, XO and captain.

auxiliary vent-and-blow system: back-up vent-and-blow system in case of failure of main systems. May be used for diving and surfacing of submarine.

bathythermograph: instrument to measure changes in water temperature at different depths. Also used to measure velocity of sound in water. Sensors located in top of fin and keel.

BRN mast: supplies submarine with instantaneous navigation information to lock down its latitude and longitude at PD.

bubble: ‘up bubble’ means bow of submarine is angled up; ‘down bubble’, bow angled down; ‘zero bubble’, boat kept steady on depth. Controlled by afterplanesman.

casing: outer non-watertight upper hull of submarine, designed for hydrodynamic performance. Pressure hull is the inner hull.

CEP (contact evaluation plot): time-bearing plot constantly in operation on patrol where every sonar contact is plotted so its course, range and speed can be calculated for firing solution or to avoid collision.

control room: centre of operations, where captain commands submarine and planesmen manoeuvre, surface, dive, and go to and from PD using ship control console. Houses attack and search periscopes, attack team fire-control and plotting systems. Systems console located here, which controls ballast and trim pumps, hover pump and periscopes. Slop, drain and sewage tank is blown here and hydraulic system monitored.

Coulport (Royal Navy Armament Depot Coulport): on Loch Long, Scotland. Military facility that stores and loads Britain’s nuclear weapons carried by submarines, first Polaris, then Trident.

1 Deck: nav centre, control room, wireless office, sound room, sonar console space, electronic warfare (EW) shack containing radar room, electrical equipment space with closed room containing navigator’s maps.

2 Deck: entertainment and living spaces: wardroom and officers’ bunks, senior rates’ mess and annex, upper bunk space, coxswain’s office, sick bay, galley, scullery, junior rates’ dining area and mess in upper level of torpedo compartment.

3 Deck: senior and junior rates’ bunks, junior rates’ toilets, laundry, AMS 1, missile control centre.

dolphins: gold submariners’ qualification badge to denote fully qualified submariner, gained after passing on-board oral examination. Panel consists of XO, chief engineer and coxswain. Worn on upper-left chest.

EBS (emergency breathing system) mask: used in emergencies when fire causes poisonous smoke to billow through submarine. Plugged into various couplets around submarine, known as built-in breathing system, which supplies fresh supply of air.

emergency surface procedure: to avoid catastrophic fire, flooding and sinking of boat, all watertight bulkhead doors are shut, full ahead is selected on engine telegraphs, emergency air supply is used to fill ballast tanks with air, causing submarine to surface as quickly as possible with planesmen controlling pitch.

Faslane (HMS Neptune): on Gare Loch, Scotland. One of Royal Navy’s three operating bases. Centre of naval operations in Scotland and home of the nuclear missile-carrying submarines, in my day Polaris, now Trident.

fire-control system: computerised system on submarines, designed by Ferranti and Royal Navy, using series of pre-set algorithms and other tactical information from on-board time-bearing plots and sonar room to calculate firing solutions for torpedoes to target and hit enemy vessels.

flying the boat: phrase suggesting submarine has similar moving characteristics to aircraft while dived, with pitch and depth controlled by foreplanes and afterplanes tilted either up or down to make submarine push upwards to surface or dive towards deep. Amount of angle on planes coupled with speed of boat determines angle of descent or rise, just as an aircraft’s lift by its wings is determined by speed and angle of attack.

gash: collective name for all the rubbish on a submarine, collected, crushed and fired out by gash gun into ocean.

goffa: non-alcoholic soft drink.

HMS Dolphin (Gosport): former shore-side centre for submarine training. Royal Navy Submarine School was relocated to HMS Raleigh (Torpoint) in 1998.

LOP (local operations plot): time-bearing plot using information from sound room or periscope to calculate target motion analysis on ship or submarine contacts.

PD (periscope depth): depth equal to length of periscope when dived.

Perisher: Submarine Command Course, so-called because candidates pass or perish. Run twice a year for c. 24 weeks, taking in simulation exercises shore-side and sea-going exercises on nuclear submarine. Success leads to second-in-command, then captaining nuclear submarine. Failure, a bottle of whisky and never again setting foot on submarine.

pipe: boatswain’s call used by quartermaster to pipe aboard captain on change of crews and pipe exiting captain off boat. Also used for flag officers – rear admiral and above – if visiting boat.

Polaris: Britain’s first submarine-based nuclear ballistic missile system, in service from 1968 to 1996, when the last Resolution-class submarine in service, HMS Repulse, was decommissioned.

reactor: nuclear reactor in reactor compartment powers submarine, generating heat that creates steam to provide power for turbines, which turns propeller, and for all electrical equipment and machinery to maintain life-support systems.

‘Resolution’ class: four nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) built for Royal Navy as part of Polaris programme, each armed with up to 16 UGM-27 Polaris A-3 nuclear missiles. The capital ships of the day, named after surface ships with a glorious past: Resolution, Revenge, Repulse and Renown.

scram: reactor shutdown to ensure core remains safe and doesn’t overheat, melting the boat.

scran: collective term for food, originally naval acronym for sultanas, currants, raisins and nuts once given to fight scurvy.

scrubbers: used to remove CO2 from submarine so crew don’t die of asphyxiation.

SETT (submarine escape training tank): vast concrete tower at HMS Dolphin, Gosport, where simulated escapes take place.

SINS (ship’s inertial navigation system): internal navigation system, fitted with gyroscopes, accelerometers and velocity meters, that constantly updates submarine’s position.

SSN (nuclear-powered attack submarine): nuclear submarine not carrying nuclear weapons, known as hunter-killers for ferocious pursuit of Soviet submarines. HMS Conqueror, which sank the Argentinian General Belgrano, was an SSN. They were armed with torpedoes and anti-ship missiles.

SSBN (nuclear-powered ballistic missile-carrying submarine): see ‘Resolution’ class.

tactical systems team: part of warfare team, providing complete tactical picture for captain and XO using information from sonar via sound room and periscopes if at PD, through use of target motion analysis to calculate course, speed and range of any given contact.

thermocline: temperature differentials within body of water due to seasonal variation, local conditions or latitude and longitude that give submarines acoustic blanket to hide in from sonar.

Trident: current British nuclear missile system that began replacing Polaris in 1994.

warfare team: team responsible for fighting the submarine under leadership of XO, who in turn reports to captain.

work-up: sea trials in front of onboard teaching staff ensuring crew are capable of taking submarine on deterrent patrol.

wrecking team: engineering team looking after forward part of submarine and watch-keeping at systems console in control room.

Ranks and roles

AB (able seaman): Royal Navy rating in seaman branch, above ordinary seaman and below leading seaman.

afterplanesman: controls afterplanes at bow of submarine, tilting them back to surface, forward to dive. Also steers submarine to left (port) and right (starboard).

captain: commanding officer of submarine, also referred to as ‘skipper’, ‘the man’ or ‘God’.

chief ops: chief petty officer in charge of sound room as well as sonar ratings and any other senior rates who are sonar specialists. A highly experienced sonar operator, usually excels at quizzes.

chief wrecker: chief engineer who operates and watch-keeps at systems console, leading a team of junior rate wreckers maintaining engineering systems at front end of boat.

coxswain: ship’s senior rating, normally with rank of chief petty officer or warrant officer.

CPO (chief petty officer): senior non-commissioned officer in most navies, rank between petty officer and warrant officer.

foreplanesman: controls operation of foreplanes from the control room. Works in conjunction with afterplanesman to maintain correct pitch and depth of submarine, crucial when at PD.

junior rates: heartbeat of submarine, keeping her alive and buzzing every day. Responsible for storing ship, cleaning and scrubbing out for inspections, watchkeeping duties, and also for most of drinking and entertainment while at sea.

Lt Cdr (lieutenant commander): commissioned officer in Royal Navy, above a lieutenant and below a commander. Heads of departments on submarine were all lieutenant commanders, as was XO.

leading radio operator: leading hand working in wireless office monitoring signals from Command Centre at Northwood. Equivalent rank to corporal in Army.

leading seaman: either a sonar operator or tactical systems operative, a key member of attack team.

leading steward: personal steward to captain, also likely to do a turn on ship control steering submarine.

master-at-arms (MAA): see coxswain.

MEM (marine engineering mechanic): driving force on boat, ensuring all mechanical and life services from nuclear reactor to air purification and laundry tick over. Most importantly, keeps toilets flushing.

MEO (marine engineering officer): senior engineering officer tasked with safe working and operation of nuclear reactor and all other engineering systems. Reports to captain. Usually at rank of Lt Cdr. Mine was cerebral and friendly, and played a mean Spanish guitar.

NO (navigating officer): seaman officer in charge of navigation, holds charts and maps of patrol area in a locked room on 1 Deck. Member of warfare team. Reports to XO. At rank of lieutenant. Known as Vasco or pilot.

OOW (officer of the watch): seaman officer, captain’s representative while watch-keeping at sea, preserving safety of submarine in all aspects, especially avoiding grounding and collision. Accountable to captain for safety of entire submarine while on watch.

QM (quartermaster): in charge of external security of submarine, managing ship’s crew inventory so no one gets on board without his knowledge. Also helps with logistics of storing ship.

RPO (reactor panel operator): monitors reactor and associated electrical and propulsion systems from manoeuvring room.

senior rates: non-commissioned officers, either petty officers or chief petty officers.

surgeon lieutenant: doctor on board, hides in sick bay armed with paracetamol. Unlikely to display standard bedside manner. At rank of lieutenant. Also does turn at ship control on patrol.

TASO (tactics and sensors officer): seaman officer, part of warfare team. Reports to XO. At rank of lieutenant.

WEM (weapons engineering mechanic): junior rating looking after maintenance of torpedoes and electrical systems of sonar and other computer systems.

WEO (weapons engineering officer): in charge of loading, maintenance and firing of nuclear weapons and torpedoes. Reports to captain. Usually at rank of Lt Cdr.

XO (executive officer): the Jimmy, Number 1 or second-in-command of submarine. Like captain, will have passed Perisher course. Overall in charge of warfare team. Reports to captain. Usually at rank of Lt Cdr.

Introduction

The Cold War, deep under the North Atlantic. Probably, but who knows? I certainly don’t. Right now we could be anywhere. All I can hear are whales communicating with each other, a haunting sound that’s somewhat tragic in delivery, like a loved one bereft for eternity.

Theoretically, we are 15 minutes from the start of Armageddon. That’s the time it would take between us receiving the firing signal from the prime minister and the nuclear warheads being launched. I’m on patrol – submarine patrol – aboard a sizeable chunk of Britain’s nuclear deterrent. We are the hidden. We see and hear everything, but only ever listen – we never communicate. A highly trained, motivated, elite team of submariners, we’re the best in the business. It’s the middle of the night in the control room, all the dials bathed in soft red lighting. I haven’t slept well for days; I’ve got bad skin and my body clock has gone haywire. And then it happens.

A distant noise. Panic sets in. Undetected by our sonar, it’s as if the intruder has come from nowhere. The crew freeze, the next 30 seconds drip by … What is it, friend or foe? Have we been detected and compromised? Suddenly, the tell-tale sound of a submarine’s propeller screams over the top of us no more than 50 feet away. All hell breaks loose. I literally dive full-length into a seat on the fire-control system, as we scramble around looking for answers. We assign the rogue sub a target number and track it as it passes to the stern of us, then, phantom-like, gradually fades away to the east, never to be heard from again.