Полная версия:

The Porcelain Thief

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2015

First published in the United States by Crown in 2015

Copyright © Huan Hsu 2015

Huan Hsu asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design by Sarah Greeno

Cover shows details from a Dish decorated with a lake scene with terraces, pavilions and pagodas, from Jingdezhen, China, Qing Dynasty, 1644-1911 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London; Details from a porcelain vase with underglaze blue decoration, 1662–1722, Chinese School, Qing Dynasty, 1644-1912 © Cleveland Museum of Art, OH, USA/Gift of Mrs E. S. Burke, Jr./Bridgeman Images; Details from a vase from Jingdezhen kilns, Jiangxi Province, China, 1662-1722 © V&A Images/Alamy; Details from a Jingdezhen Ware Beaker © Royal Ontario Museum/Corbis

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007479436

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780007479429

Version: 2015-02-27

Dedication

To my family,

the treasure I always had,

and to Jennifer,

the treasure I never expected to find

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Author’s Note

Family Tree

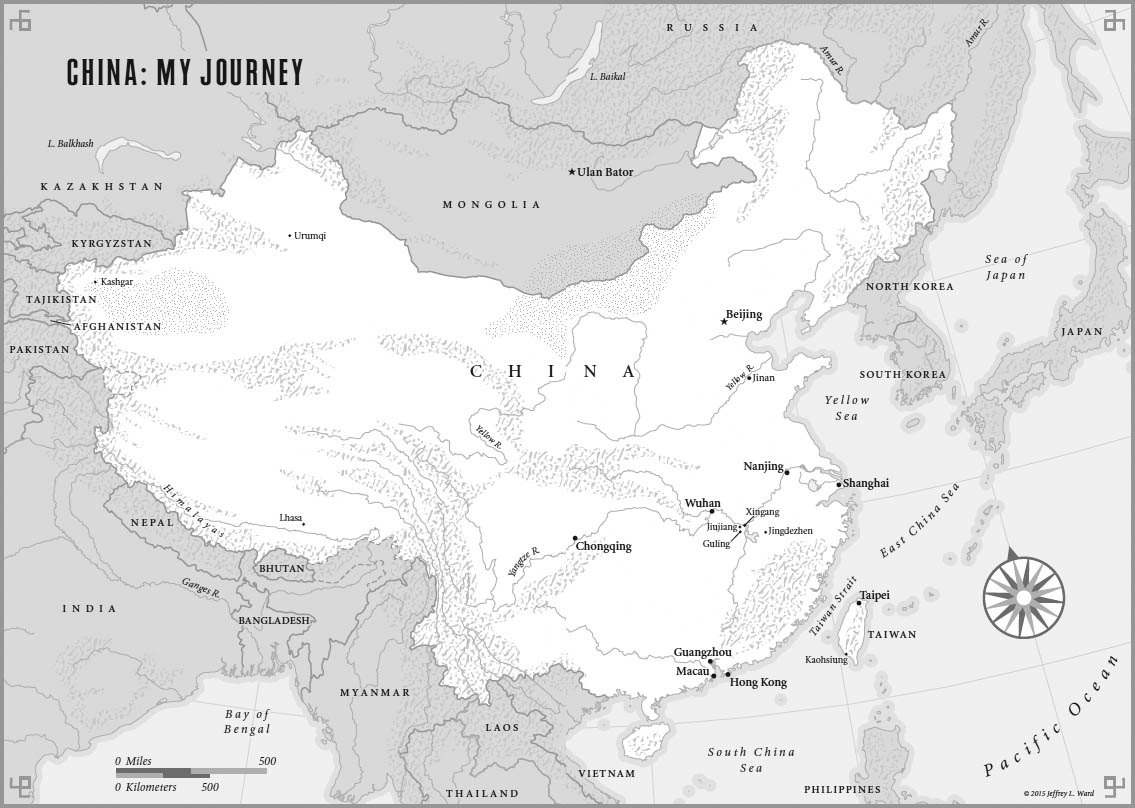

Map 1 China: My Journey

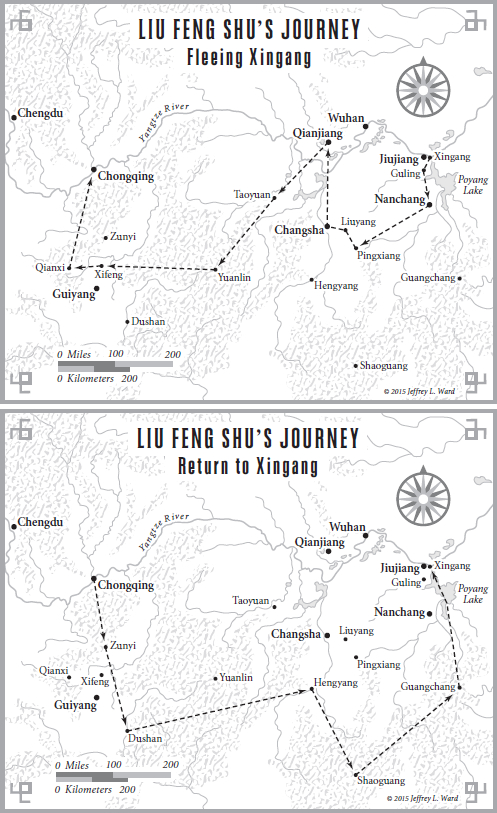

Map 2 Liu Feng Shu’s Journey

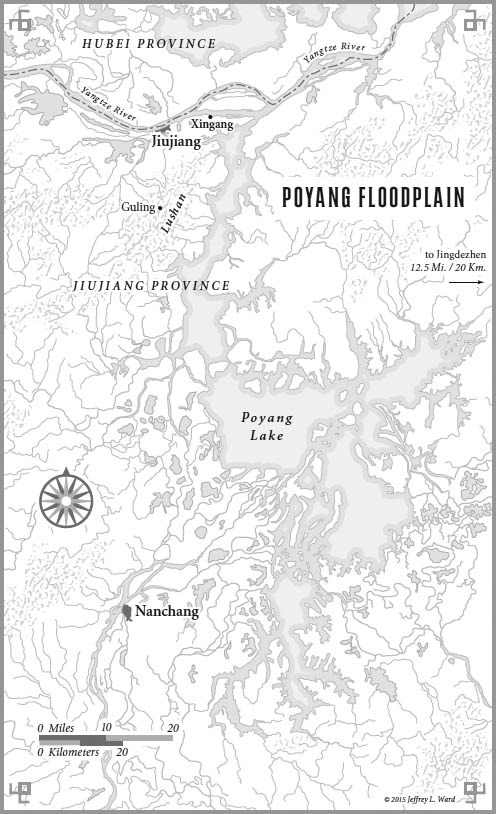

Map 3 Poyang Floodplain

PROLOGUE

1. THIS IS CHINA

2. A CHICKEN TALKING WITH A DUCK

3. LIU FENG SHU

4. PANDA CHINESE

5. THE ORPHAN

6. STREET FIGHT

7. JOURNEY TO THE WEST

8. THE REAL CHINA

9. END OF PARADISE

10. FROM FAR FORMOSA

11. CITY ON FIRE

12. FALLING LEAVES RETURN TO THEIR ROOTS

13. ALL DEATH IS A HOMECOMING

14. NANJING

15. NORTHERN EXPEDITION

16. A STUMBLE FROM WHICH THERE IS NO RECOVERING

17. THE NINE RIVERS

18. THE LONG VALLEY

19. XINGANG MARKS THE SPOT

20 CHASING THE MOON FROM THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA

Picture Section

A Note on Sources

Index

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

THIS BOOK RECOUNTS MY TIME IN CHINA FROM 2007 TO 2010, and then the summer and fall of 2011. Although this is a work of nonfiction, any attempt to reconstruct recent history is inherently subjective, and my guiding principle was to tell a coherent story about China, my family, and my search for my great-great-grandfather’s buried porcelain. Many of the people and places in this book were visited a number of times over many years. For the sake of narrative logic, I have in some instances compressed the time between these encounters, omitted extraneous details, or explained information out of time with its revelation to me. However, descriptions of people, places, or encounters themselves have not been altered, and the dialogue was recorded either as it happened or soon thereafter.

A word on translations: Many of my conversations with Chinese speakers took place in Mandarin Chinese. When translating the conversations, I tried to be faithful to my partner’s intended meaning and re-create it as I understood it in everyday English while also preserving the unique qualities of their speech. The instances where Chinese speakers use English are noted as such. I have used pinyin transliterations except for names commonly spelled otherwise, such as Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen, and the members of my family who write their names according to Wade-Giles conventions.

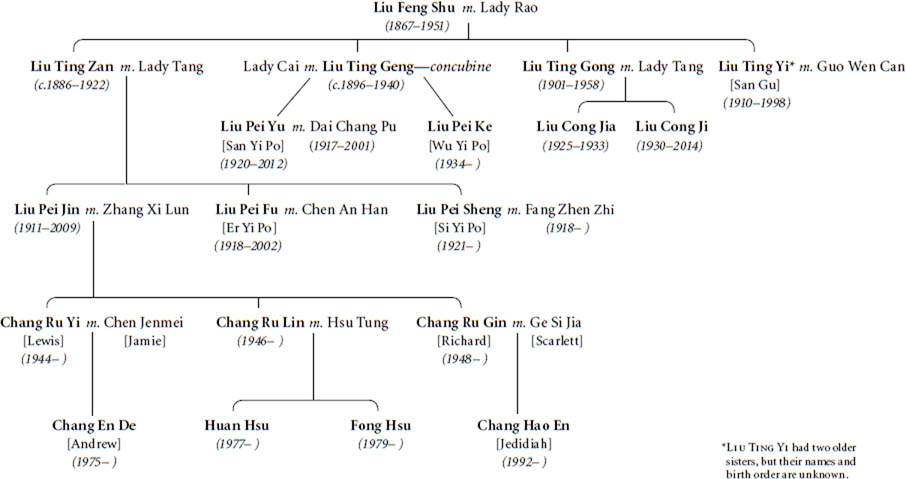

Chinese kinship terms are manifold and complicated; depending on the relationship, each family member has a unique term by which they are called. I have simplified this by referring to characters either by their given names or according to their relationship to me, except for San Gu, my grandmother’s aunt. Full Chinese names are written with the surname first, followed by the given name.

Finally, all dates have been converted from the lunar calendar to the Gregorian calendar. And the conversion rate for Chinese RMB to U.S. dollars for this book is 7:1.

Family Tree

PROLOGUE

THE FIRST SIGN OF TROUBLE CAME IN THE SPRING OF 1938.

On the tails of the snow cranes leaving their wintering grounds in the Poyang Lake estuary, Japanese planes appeared in the sky, tracing confused circles as if they had lost their flock. It soon became clear that these reconnaissance planes were not stragglers but the vanguard for another kind of migration. After taking Beijing, Shanghai, and Nanjing, the Japanese army advanced through China not like a spreading pool of water but like a gloved hand, and in the summer of 1938 its middle finger traced up the Yangtze River toward my great-great-grandfather Liu Feng Shu’s village of Xingang.

Liu presided over one of the most prominent families in Xingang, situated on a spit separating the Yangtze River and Poyang Lake, China’s largest freshwater body, like a valve. His estate included most of the arable land along the river, worked by a small army of sharecroppers, and a number of residences at the western edge of the village, the largest being his own. Guarded by a trio of stately pine trees, the sprawling stone abode fronted the road heading into the nearby city of Jiujiang, a major trading and customs port. There lived a coterie of daughters-in-law, grandchildren, and servants; the eldest of Liu’s three sons, my great-grandfather, died of tuberculosis in his thirties, and his school-aged children, as well as those of Liu’s surviving sons, lived with him while their fathers worked elsewhere in the province, a common arrangement in Chinese families. My great-great-grandfather filled the rooms with objets d’art befitting a scholar who had passed the imperial civil service exam, including his prized collection of antique porcelain. Accumulated by the crate, some of the items dated back hundreds of years to the Ming dynasty and had once belonged to emperors, and for all my great-great-grandfather’s other forms of wealth, these heirlooms, as enduring as they were exquisite, best represented the apogee of both family and country. Across the road, beyond the communal fishpond, dug into a hill that gathered the setting sun, was the cemetery where eleven generations of his ancestors kept watch over his prosperity.

As the summer went on, phalanxes of Japanese bombers soared over Liu’s fields to drop ordnance on westerly cities, unencumbered by a Chinese army with pitiful air defenses. According to the newspapers that Liu picked up in the mornings from the general store down the road, Republic of China president Chiang Kai-shek was prepared to stage a vicious defense of Jiujiang and had nearly one million troops dug in along the Yangtze. The presence of Chinese soldiers became a regular sight in Xingang, if not a welcome one, given the Nationalist army’s reputation for incompetence and venality.

And now Chinese soldiers had taken up residence in Liu’s house. Despite outnumbering the Japanese three to one, the Chinese resistance lasted mere days. Xingang stood in the path of the retreat, and the army had no qualms about demanding food and board from the local gentry. The rice and firewood that Liu had set out for them was not enough, the soldiers said. They eyed the house’s heavy door bar and prepared to hack it apart for fuel. “You can’t use that for kindling,” Liu protested. “We need it to lock our door.”

The argument turned physical, and a pair of soldiers began to beat Liu with a stick. Three of his granddaughters had been herded into a back room out of sight of the soldiers and watched the commotion from a window, horrified, until they couldn’t bear it anymore. Pei Fu, the oldest one still at home, newly graduated from a Methodist boarding school, instructed Pei Yu, not yet a teenager, to run into the village and fetch the elders. Then she and Pei Sheng, the second youngest but the boldest, sprinted into the fray, jumping on the soldiers’ backs and thrashing them while they tried to pull their grandfather away. “You guys fought so poorly, ran away from the battle, and you still dare to hit an old man?” Pei Sheng shouted. “No wonder you’re losing the war!”

Pei Yu found the elders, who alerted the commanding officers, and all parties converged on the house. The girls explained what they had witnessed, and the elders vouched for the girls. The chagrined commanders forced the offending soldiers onto their knees before Liu and offered to execute them. “Oh, don’t kill anyone,” Liu said. “That’s not right, either. You come here and we give you food, a place to stay, and you act badly. As long as you understand what you did wrong, that’s enough.” He made them kowtow and apologize, and for the rest of their stay, the soldiers didn’t even dare to touch the firewood left out for them without first asking. “We’re afraid of what the three tigresses might do,” they said.

My great-great-grandfather was not naïve about war. In midlife he had witnessed the end of dynastic China and the birth of a republic when revolutionaries overthrew the Qing monarchy in 1911, ending more than two thousand years of imperial rule. Ten years before the Japanese encroached, Chiang Kai-shek’s campaign against local warlords had swept through the area, followed by sporadic skirmishes between Chiang’s Nationalists and the upstart Communists. Each time feng liu yun san, “the winds flowed and the clouds scattered”; the crisis passed. Liu’s wealth and land holdings continued to grow. Still, his blood curdled from the reports of Japanese soldiers sha ren ru ma, “killing people like scything grass,” in occupied cities. He especially feared for the granddaughters still living with him at home. Most of the village men of fighting age had already left home, eager to avoid death by the Japanese or, worse, conscription into the Chinese army. Liu was a widower in his seventies and could hardly be counted upon to protect his family. As he debated whether to flee everything he had spent a lifetime achieving, he must have wondered if perhaps this time things would not return to normal.

His eldest granddaughter—my grandmother—was safe, ensconced in neutral Macau as a high school chemistry teacher at a missionary school. He allowed Pei Fu, the second oldest and my grandmother’s middle sister, to marry into a family he despised, figuring a woman wedded to a good-for-nothing was still safer than remaining unmarried during wartime. He had already sent away his one grandson, the sole heir to the family fortune, with his youngest daughter, another science teacher whose local missionary school had relocated to the Chinese interior. That left my grandmother’s youngest sister, two of her cousins, a daughter-in-law, and a long-serving footman, Old Yang.

When the soldiers moved on, Liu and Old Yang waited for the sun to set and went into the garden with shovels and picks. Over the next few nights, they removed a patch of flax and dug a large hole, deeper than a man was tall and as wide as a bedroom, and lined the walls with bamboo shelving. Working by moonlight after the village had gone to sleep, they filled the vault with the family’s heirlooms: intricately carved antique furniture, jades, bronzes, paintings, scrolls of calligraphy, and finally, Liu’s beloved porcelain collection. Vases of every shape and size; painted tiles of Chinese landscapes; hat stands; figurines of the Fu Lu Shou, the trio of Buddhist gods that represented good fortune, longevity, and prosperity; decorative jars, plates, and bowls; tea sets; the dowries for his granddaughters. Liu and Old Yang packed the porcelain in woven baskets lined with straw, and once the vault could hold no more, they sealed it with boards, covered it with soil, and replanted the flax.

A few nights after the burial was completed, Liu heard a knock on his door. He opened it to find a raggedy Chinese soldier, who asked if he could spare something to eat. Liu took him in and fed him. The soldier ate as if it were his first meal in weeks. When he finished, he looked up from his bowl. “Mister, is your family still here?” the soldier asked.

“Yes, they are,” Liu said.

“Why have you not left yet?” the soldier said. “The city has fallen. The Japanese are here.”

The next morning the family packed as much jewelry and silver coins as they could fit into their pockets and bundled their clothes in knapsacks. They stuffed winter and summer clothing for five people into a woven basket that Old Yang, who had no family but for the Lius, carried on a bamboo shoulder pole. The thousands of extra silver dollars that were too heavy to carry were thrown into jars and buried in a hastily dug hole in the floor of the living room. Then my great-great-grandfather barricaded the heavy front doors and joined the Chinese retreat.

Seventy years later I went to China to find what he buried.

[1]

THIS IS CHINA

IF MY PARENTS EVER TOLD ME ABOUT MY GREAT-GREAT-GRANDFATHER’S buried porcelain, it had never registered. Growing up in Utah, I paid little attention to family stories, most of which concerned overcoming hardships that I, preoccupied with overcoming my own hardship of being Chinese and non-Mormon in Salt Lake City, couldn’t relate to and didn’t care to hear about. Any reminders of my family history only impeded my goal of being as American as possible or, short of that, as un-Chinese as possible, a rebellion that included working harder at sports than math and refusing to apply to Harvard. As far as I was concerned, the Chinese people in my life, with their loud, angry-sounding manner of speaking and odd habits, were from another planet and had traveled to Earth for the sole purpose of embarrassing me.

But I always loved to dig, and as a child I made many holes in the backyard looking for arrowheads or fossils, usually giving up once I hit a thick layer of clay a few feet down, which was about the same time my mother noticed what I was doing to her lawn, anyway. As I got older, this preoccupation manifested itself in searching for things thought lost, nonexistent, or impossible to find. I spent most of my time in an MFA program ignoring my classmates’ suggestions to write about being Chinese, instead researching the unique discovery of an antibiotic during World War II—it was isolated in the tissue of a little girl who had been hit by a car—and trying to track down that girl. As a journalist, some of my favorite stories also involved hunting: looking for edible mushrooms in city parks, poking around the storerooms of Washington, D.C., institutions for forgotten art, stalking pickpockets with undercover police, and profiling an obsessive amateur archaeologist cataloging the Paleo-Indian history of his neighborhood (with whom I participated in a number of surreptitious excavations, satisfying an old itch).

After taking a job at the Seattle Weekly, I visited the Seattle Art Museum for a story and found myself drawn to SAM’s Chinese porcelain collection. My parents never owned any such porcelain, and my encounters with it were limited to mentions of Ming vases (always pronounced “vahz”) as signifiers of wealth in pop culture, but perhaps because I had just moved to my fourth city in seven years, the collection elicited some subconscious familiarity with it. My favorite object was a little red “chrysanthemum” dish, about six inches in diameter, with scalloped edges that caught the light in a way that rendered them almost translucent. Decorated with a square of sixty-four gold Chinese characters, all the SAM curators could tell me was that it had been fired sometime in the late eighteenth century.

Since the SAM curators had never bothered to translate the text, I called my father, a physics professor who, just for fun, once spent a sabbatical summer doing conservation work at Chicago’s Field Museum. His nerdiness caused me no small amount of anguish when I was young (he wore a pocket protector well into my high school years), but he was also the exact kind of nerd who could translate the dish for me.

The poem, my father told me, had been penned by the owner of the plate, the fifth emperor of the Qing dynasty, Qianlong, and was a paean to the makers and craftsmanship of the dish. And because my father is incapable of answering any question without first fully contextualizing the answer in the most pedantic way possible, he went on to explain that Qianlong was known for leaving his mark, in the form of calligraphy, stamps, and poems, on many precious pieces of art—a common practice among Chinese collectors. “His calligraphy was okay,” my father said, “but he is not remembered as a poet.”

Qianlong was one of the great figures in Chinese history, both a successful military leader who expanded China’s territory by millions of square miles and a devoted patron of the arts. He commissioned one of the most ambitious literary projects in Chinese history, the creation of a library of classic Chinese texts, and fancied himself a bard. During his reign the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen, about ninety miles east of my great-great-grandfather’s village and the center of world porcelain production, reached their zenith in technology and quality. But Qianlong was also famously sinocentric, refusing to increase trade with the West, and rejecting the Industrial Revolution as a fad and Western technology as toys. At the height of Qianlong’s rule, China was the richest country in the world by a wide margin. When he died in 1799, his treasury was empty, porcelain exports to Europe had all but stopped, and centuries of progress and innovation were undone, setting China on course for humiliating defeats in the Opium Wars, the Sino-Japanese Wars, massive domestic rebellions, and finally, the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and the eventual rise of Communism.

“One more thing,” my father said before we hung up. “Your mother’s family had some porcelain. You should ask her about it.”

Once my mother told me the story of my great-great-grandfather’s porcelain, Qianlong’s crimson plate, a burst of bloody color amid the mostly white pieces surrounding it, became more than just an example of the imperial porcelain that my family might have owned. It was the beginning of an epic narrative that began with my family’s buried heritage and extended to my standing there in a Seattle museum surrounded by ceramics that, for all I knew, might have once passed through my great-great-grandfather’s hands. Here was the house of Liu, ascending nicely through post-imperial China, when the Japanese invaded and they lost everything. The guns had barely cooled from that conflict when the Communists took over, and my family lost everything again when they fled to Taiwan. In Taiwan my grandmother started from nothing once more, scrimping and saving to send her children to college in America, where things like Communist takeovers didn’t happen. The longer I looked at that red chrysanthemum plate, the more I wanted to touch it, feel its weight, and run my fingers over its edge, which, like its country’s—and my family’s—history, was anything but smooth.

I harangued my mother for more details: How much porcelain and silver was buried? Were there really imperial pieces in the collection? Had anyone ever tried to dig it up? What happened to it? But to my surprise and consternation, neither my mother nor her two brothers, who had all been born on mainland China, emigrated to Taiwan as children, and emigrated again to the United States for graduate school, knew or cared much about this part of their history.

My best source of information, my mother said, would be my ninety-six-year-old grandmother, who had returned to China after my grandfather died to live with my uncle Richard. The youngest and most evangelical Christian of my mother’s siblings, Richard had started out as an engineer at Texas Instruments and risen to a management position setting up manufacturing facilities in Europe. At age fifty, after spending two decades with Texas Instruments, having built his dream house in a north Dallas suburb where one of his neighbors was the quarterback for the Dallas Cowboys, he took an early retirement and established a semiconductor foundry in Taiwan called Worldwide Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, or WSMC. Richard served as the president of WSMC until 1999, when he sold the company to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, or TSMC, the behemoth global leader whose market cap was nearly 30 percent of Taiwan’s gross domestic product, for $515 million. In its report on the deal, The Wall Street Journal dubbed Richard the “Taiwanese Tycoon.”

On that same day he claimed to have received a vision from God to start a similar company on mainland China as a way of both developing its high-tech industry and spreading the gospel there. With a $1 billion investment from the Chinese government, and plenty more from top venture capital firms, Richard installed himself as president and CEO and named his new enterprise Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, or SMIC. He broke ground on his venture in Shanghai while I was finishing up college and heading off to work at my first job, in a high-tech public relations agency in San Francisco, and he asked me to work for him every chance he got. My mother posited that he wanted me as his assistant, where I would learn the company and eventually take over for him. The stock options alone should have been enticing enough, but I demurred each time, not interested in the work, the industry, or China. My other uncle, Lewis, bought up as many pre-IPO shares as he could, and the general sentiment was that the stock could double, even triple, its initial price. Lewis would sometimes phone my mother just to berate her for not forcing me to join the company. “There’s a million dollars right there in front of him,” he’d howl, “and he can’t be bothered to bend over and pick it up!”