скачать книгу бесплатно

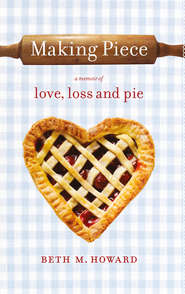

Making Piece

Beth M. Howard

When journalist Beth Howard’s young husband died suddenly, baking was the one things that still made her smile.So Beth hit the road in their old camper van, travelling across America and bringing Pie to those who need it most. Powerful. Courageous. Triumphant. This is Beth’s true story about finding strength, second chances and spreading the joy of pie.

“Strange is our situation here upon earth. Each of us comes for a short visit, not knowing why, yet sometimes seeming to a divine purpose. From the standpoint of daily life, however, there is one thing we do know: That we are here for the sake of others … for the countless unknown souls with whose fate we are connected by a bond of sympathy. Many times a day, I realize how much my outer and inner life is built upon the labors of people, both living and dead, and how earnestly I must exert myself in order to give in return as much as I have received.”

~Albert Einstein

“We must have pie.

Stress cannot exist in the presence of a pie.”

~David Mamet

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BETH M. HOWARD is a journalist, blogger and pie baker. Her articles have appeared in Elle, Shape, Travel + Leisure and Natural Health, among many other publications. In 2001, at the height of the dot com boom, she quit a lucrative web producing job in San Francisco to bake “pies for the stars” at a gourmet deli in Malibu, California. Her popular blog, The World Needs More Pie, which she launched in 2007, regularly receives national press that has included Better Homes and Gardens, the New York Times and NPR’s Weekend Edition. Beth lives in Eldon, Iowa, in the famous American Gothic House.

Making Piece

A Memoir of

Love, Loss

and Pie

Beth M. Howard

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

For Marcus Iken

Liebe meines Lebens

They say spirits read everything.

I say you didn’t just read this book, you helped me write it. Please consider it a love letter and apology to you … until we meet again and I can tell you in person.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It takes a lot of people to tell a story. It takes a tremendous amount of support to recover from grief. These are the people, who, during the past two years, helped me through the most unimaginable darkness. Some of them are featured in the book, some read my early drafts, some knew Marcus, some were just really great inspiration or influence, some made me laugh, some even made me pie. Regardless of their direct involvement in Making Piece, these are the people who have touched my life and who deserve my public gratitude. This book would not exist without them.

Deidre Knight (my literary agent, a goddess and Steel Magnolia), Ann Leslie Tuttle (my compassionate and enthusiastic editor) and the staff at Harlequin Nonfiction.

Team Marcus (and the first three numbers in my speed dial): Nan Schmid, Melissa Forman and Alison Kauffman.

My grief counselor and godsend: Susan Hodnot (How did I get so lucky?!).

My family: my parents, Tom and Marie Howard; my sister, Anne (thanks not only for reading my manuscript, but for the supersoft pajamas, the “Daisy” perfume and Bach Flower Essence “grief drops”—that care package really cheered me up); my brothers, Tim, Michael, Patrick; Patrick’s family; and my aunt Sue and uncle Mike Finn.

In Terlingua: John Alexander, Cynthia Hood, Mimi Webb Miller, Betty Moore and Ralph Moore (three weeks of dog sitting while I was at Marcus’s funerals earns you a lifetime supply of Guinness and guitar strings, Ralph).

In Portland: Frank Bird, Arlene Burns, Bennett Burns and Andrew Rowe, Janine Canella, Colleen Coleman, Saumya Comer, Liz Heaney, Don Hofer, Stacy James, Thomas Lehman, Donn Lindstrom, Sylvia Linington, Megan McMorris, Marty Rudolph and Heather Wade. Ein besonderes Dankeschön to the Portland/Freightliner gang, in particular: Dayna and Gerald Freitag; Julia Hofmann, Joerg, Katrin and Nolan Liebermann; and Lyndsay, Andreas and Heidi Presthofer and Rachel Wecker.

In and around Eldon, Iowa: Priscilla Coffman; Meg and Jeff Courter and family; Linda Durflinger; Patti Durflinger (who delivered dinners to my back door to keep me writing); Don and Shirley Eakins; Cari Garrett; Brenda Kremer; LeAnn Lemberger; Allen and Rosie Morrison; Molly Moser (who holds the distinction of being the very first reader of my book and my salvation for getting through my first Iowa winter in thirty years and whose painting inspired my book title); Shirley and Gene Stacey; Carrie, Chloe and Tony Teninty; Bob and Iola Thomas; Jerome Thompson; and the ladies at Canteen Lunch in the Alley (Yvonne Warrick, Linda Grace and the rest of the crew).

TV Shoot in California: Janice Molinari (my coproducer—thank you for your laughter, your singing, your vision for the pie show and for giving me a purpose when I desperately needed one). Sunny Sherman and Martha Gamble of The Apple Pan, Natalie Galatzer of Bike Basket Pies, Bill Miller of Malibu Kitchen, Karen Heisler and Krystin Rubin of Mission Pie, Dorothy Pryor of Mommie Helen’s, the Law family of Oak Glen, Carlene Baime, The Doscher Family, Kathy Eldon and Amy Eldon Turteltaub, Prudence Fenton and Allee Willis, Susanne Flother and Anthony Scott, Elissa Harris, Jeff Mark, Thelma Orellena, Elana Pianko, Shanti Sosienski and Jane Windsor.

Pie People: Kathleen Beebout, Gina Hyams, Arlene Kildow, John Lehndorff, Tricia Martin (also my ace web designer), Mary Pint (the original “Pie Lady”), Lana Ross, Mary Spellman (my pie mentor, to whom I’m forever grateful), Mary Deatrick and Linda Hoskins of the American Pie Council, and Arlette Hollister, Patt Kerr and the food crew of the Iowa State Fair.

Friends, colleagues, readers, advisors and general hand-holders: Christine Buckley, John and Laura Climaco, Susan Comolli, Barbara DeMarco-Barrett, Julia Gajcak, Maggie Galloway, Angela Hynes, Steve Johnson, Jim Keppler, Ann Krcik, Dana Long, Patti Nilsen, Alayne Reesberg, Maria Ricapito, Jean Sagendorph, Andrew Salomon, Sue Sesko and Jonathan Wight.

My blog followers (who encouraged me to keep writing about my grief publicly): Chris Bauer, Sigrid Holland, Jeff “Prop” O’Brien, Kelly Sedlinger and Paul Szendrey.

Journalists (the people who discovered my story and wanted to share it): Jennifer Anderson (Portland Tribune), Mike Borland (WHO-TV), Steve Boss and James Moore (KRUU-FM), John Gaps III, Kyle Munson and Tom Perry (Des Moines Register), Lianne Hansen and Jacki Lyden (NPR), Kelly Kegans (Better Homes and Gardens), Katherine Lagomarsino (Spirit magazine), Ron Lutz (Our Iowa), Trevor Meers (Midwest Living), Meghan Rabbitt (Natural Health) and Peter Tubbs (Better TV).

Pie makers and pie lovers everywhere: you all help make the world a better place.

And last, but certainly not least: Banana Cream Pie.

PROLOGUE

I blame pie. If it wasn’t for banana cream pie, I never would have been born. If my mom hadn’t made my dad that pie, the one with the creamy vanilla pudding, loaded with sliced bananas and covered in a mound of whipped cream, the one that prompted him to propose to her, I wouldn’t be here. Think about it. The anatomical shape of bananas. The pudding so luscious and moist. The cream on top as soft as a pillow on which to lie down and inspire certain sensuous acts. My parents were virgins and intended to stay that way until they exchanged vows at the altar. That pie made wedding plans urgent. If it wasn’t for that pie, they may never have gotten married and had kids, had me.

If I had never been born, I never would have learned to make pie; not just banana cream, but apple and strawberry-rhubarb and chocolate cream and peach crumble and many others. If I had never been born, I never would have grown up to become a writer and gotten that job at the dot com that paid so well, but stressed me out so much that I quit to become a full-time pie baker in Malibu. If I hadn’t gotten that baking job, I never would have made pies for Barbra Streisand and Steven Spielberg, and I never would have taken time off to go on that road trip, the one where I ended up at Crater Lake National Park and met Marcus Iken that night in the hotel lobby.

If I had never met Marcus, never fallen in love with him and his almond-shaped green eyes, exotic German-British accent and those odd-yet-elegant leather hiking boots that laced up at the sides, I never would have invited him to join me at my friends’ wedding in Tuscany. And thus, I never would have taken the train from Italy to his apartment in Stuttgart, Germany, carrying that pie I baked him, the apple one heaped high with fruit, drowning in its own juices and radiating the seductive scent of cinnamon, the one that made him realize I was like no woman he’d ever met before and that he couldn’t live without me—the pie that prompted him to propose to me.

If it wasn’t for pie, I never would have been born. I never would have married Marcus and moved to Germany, to Oregon and then to Mexico with him. If I had never married him, I would not have been the one listed as the emergency contact, the one who got The Phone Call that day. I never would have learned how a call from a medical examiner can mean only one thing, how harsh the word would sound in my ears—“Deceased,” he’d said—and how that word would haunt me, change my life, change me.

If I had never been born, I never would have known what it feels like to lose Marcus, never known what his sexy, athletic body, the body I had made love to hundreds of times, looked like lying in a casket, cold, hard, lifeless, eventually cremated, his ashes buried, never to be seen again.

If only my mom hadn’t made my dad that banana cream pie. Fuck pie.

I am a pie baker and I live in the American Gothic House. Yes, the American Gothic House, the one in the iconic Grant Wood painting of the couple holding the pitchfork. It is the second most famous white house in the U.S.A., second only to the White House. Yes, the White House in Washington, D.C. The American Gothic House is nowhere near Washington, D.C. It is located in rural Southeastern Iowa in a sleepy, former railroad town called Eldon (pop. 928), and while the house is indeed white, it is decidedly smaller and humbler than the presidential one. Because it is famous and old—old as in “built in 1881” old—it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. But one doesn’t need documentation or a plaque by the front door to know the age of this house. The slanted, worn, wide-plank floorboards, the rectangular shape of the nail heads handcrafted by blacksmiths and the cracks in the front door that let in the winter drafts speak for its many years of weathering a hardscrabble life on the windswept prairie.

Living in a tourist attraction (which must be where the expression “living in a fishbowl” comes from) takes a special person. And since I live here, I guess that makes me special in that I can handle the daily foot traffic tromping across my front porch, I accept how strangers, unable to restrain their curiosity, peer into my windows, and I politely offer to snap the occasional photo of a couple striking the prerequisite pose in front of the Gothic window.

Out of the hundred-plus places I’ve ever lived, this is the first and only one where I signed a lease requiring that the “tenant shall treat the public in a friendly manner.” And mostly I am friendly. Except when I’ve had too many faces pressed up against the glass in my kitchen window. In which case, the white cotton curtain gets yanked across their hungry eyes, and I retreat to the most private room in the house: ironically, the upstairs bedroom, the one immediately behind the house’s main feature, the Gothic window.

Legend has it that this window—and the matching one on the opposite end of the second floor—was purchased via mail order from Sears Roebuck. The triangular shape of the paned glass attracted Grant Wood’s attention when he visited Eldon in 1980. He found it incongruous, if not pretentious, that such a simple white wooden farmhouse would be adorned with such an ornate, if not religious, window. Wood was so intrigued, he drew a sketch of the front of the house, returned to his art studio in Cedar Rapids, convinced his sister and his dentist to pose as the spinster daughter and dour father to represent the stoic, roll-up-your-sleeves-and-just-do-it, Midwest stereotype, painted the three individual elements onto one canvas, and the rest, as they say, is history. The house—and its window—is so famous that it attracts over 10,000 visitors a year to its remote Iowa location.

It is behind this window and its lace curtain that I sleep, dream, read, cry, snuggle with my two small dogs and escape the peering eyes of passersby. The lease also states “tenant agrees to maintain South Window curtains similar to those featured in Grant Wood’s American Gothic painting.” This is no problem, as the lace curtains came with the house. In the upstairs bedroom window, the showcase one, I simply hung white sheers over the lace curtain, which maintains the original appearance for the tourists’ photo opportunity, but adds a layer of privacy from the outside world, and keeps at bay the blazing Iowa sun, which rises around seven each morning over the neighbor’s soybean field.

On the weekends, when the weather is good, I sell pies out on the lawn of the house. I can’t say if this has ever been done before at the American Gothic House. Out of the many families that have lived here—the Dibbles, the Joneses, the Smiths—mine are certainly not the first pies to be baked inside. That would be impossible, seeing as Iowa is the pie capital of America, where pies are a way of life, baked into the fabric of Midwestern existence. Eldon, Iowa, is full of pie bakers. (I know this because I’ve sampled Arlene Kildow’s coconut cream pie. It would win first prize at the Iowa State Fair if she would enter. And Janice Chickering’s apple pie, which I haven’t tried yet, must be delicious because it wins every local pie contest.) But setting up a pie table right outside the famous house, as if it were an Amish farm stand or a Girl Scout bake sale? That might be a first.

I didn’t move into the American Gothic House to sell pies. Moving into the American Gothic House wasn’t in my plans at all. In fact, until that hot, humid, late August day that I happened upon the road sign for the house, I didn’t even know of its existence. I will tell you how and why I came to live here, how I became known as “America’s Pie Lady,” how I became adopted by the mayor and other residents of Eldon, and most important of all, how my grief began to ease and my heart eventually began to heal. I will tell you all that and more. But I have to begin further back in time.

You will find my story is a lot like pie, a strawberry-rhubarb pie. It’s bitter. It’s messy. It’s got some sweetness, too. Sometimes the ingredients get added in the wrong order, but it has substance, it will warm your insides and, even though it isn’t perfect, it still turns out okay in the end.

CHAPTER 1

I killed my husband. I asked for a divorce, and seven hours before he was to sign the divorce papers, he died. It was my fault. If I hadn’t rushed him into it, I would have had time to change my mind, and I didn’t want to change my mind again. I was sure this time. I wasn’t good at being a wife and I was tired. Marcus and I still loved each other, still desired each other, we were still best friends. But in spite of best intentions, after six years, our marriage had become like overworked pie dough. It was tough, difficult to handle and the only option I could see was to throw it out and start over.

I was a free-spirited California girl, trying to mix with a workaholic German automotive executive. Too often, it had seemed like an exercise in futility, like trying to whip meringue in a greasy bowl where, with even the slightest presence of oil, turning the beaters up to a higher speed still can’t accomplish the necessary lightness of being. We needed to throw out the dough, I insisted. Chuck the egg whites, and wash out our bowls so we might fill them again. I was impatient and impulsive, overly confident that there was something, someone better out there for me. I was also mad at him. He worked too much. All I wanted was more of his time, more of him. Asking for a divorce was my cry for attention. And since I couldn’t get his attention, couldn’t get the marriage to work, couldn’t get the goddamn metaphorical pie dough to roll, I was determined to start over. It was my fault. He died because of me. I killed him.

August 19, 2009, Terlingua, Texas

I wasn’t even halfway through my morning walk with the dogs, but the sun had already risen high above the mesa of the Chisos Mountains. We should have left earlier, but every morning started with the same dilemma. Make coffee or walk the dogs first? I loved savoring my café latte on the front porch, taking that first half hour to shake off sleep and greet the day. But the window of dogwalking time was short, so the dogs always won. It never failed to amaze me how fast the sun rises in this West Texas frontier, how quickly a summer desert morning could transition from tolerable to intolerable, how a ball of fire that was welcome at first light so quickly became the enemy to be avoided, something from which to seek escape.

Other than the dogs’ needs, the heat made no difference to me, as I had made a commitment to staying inside no matter what the weather. My plan was to spend the summer in my rented miner’s cabin, chain myself to my computer and bang out a completed draft of my memoir about how I quit a lucrative web-producer job to become a pie baker to the stars in Malibu. How I used pies as if they were Cinderella’s slipper to find a husband, and finally did fall in love and get married, to Marcus. The book was going to be a lighthearted tale of romance, adventure and pie baking. It was supposed to have a happy ending.

As I scanned the path for rattlesnakes while Jack ran ahead on the dirt road that stretched for miles through the empty, uninhabited expanse, the only thing visible on the horizon was the heat, a thermal curtain rising up from the ground, waving like tall grass in the breeze. I looked for my second dog, Daisy, the other half of Team Terrier, as I affectionately called my four-legged companions, but her light hair was the exact blond color of the desert floor, so she was much harder to spot between the scruffy patches of sagebrush.

I had gotten into a routine of jogging in the mornings, but on this day I wasn’t feeling very strong. In fact, it wasn’t the sun baking me to a crisp or the sweat running down the back of my legs that made me want to cut the walk short. It was my heart. It was racing, even though I was walking slowly—so slowly my gait was barely a shuffle. This was not normal for me. I have the strong heart and slow pulse of a professional bike racer, so much so that I often get surprised looks from doctors when probing me with their stethoscopes.

Something was wrong with me. Was I having a heart attack? I needed to get home before I collapsed and became breakfast for the vultures who were already circling overhead. I called for my dogs, who reluctantly gave up on their bunny chase to come back to me. I looked at my digital Timex watch before I turned around. It was 8:36 a.m. Central time.

I made it back to my miner’s shack, a hundred-year-old cabin made of stacked rocks chinked with mud. It was primitive but stylish, rustic but elegant, clean and sparsely furnished with just the right touches of safari chic. Decorated by my landlord, Betty, a transplant from Austin, who lived next door, the cabin’s style was Real Simple meets Progressive Rancher. The place had running water with a basic kitchen, but the shower was in a separate wing, which could be reached only by going outside. And the toilet? The toilet was an outhouse, a twenty-five-yard walk from the house. While I loved this simple living by day, I wouldn’t go near the outhouse at night for fear of walking the gauntlet of snakes and tarantulas.

With the dogs safely back in the house—no one was going to get left outside to fry in the ungodly heat—I flopped down on my bed. My heart continued to race like a stuck accelerator, and I lay there, alone, holding my body still, thinking about how this was so unusual, so intense, so unlike any sensation I had ever experienced. I remember wondering if I was going to die. Would death come so early in my life? Really? I had just turned forty-seven, I had the heart of a bike racer, I was just out for an easy morning walk with my dogs, and now this? This was how and where it was going to end? I closed my eyes and tried to stay calm. I wasn’t afraid of death. I just didn’t think I was ready for it. Besides, if I died, who would take care of my dogs?

My BlackBerry in its rubber red casing sat next to my pillow. It rang and I glanced at the screen to see who was calling. “Unknown” was all it said. Marcus called me daily and he was the only person I knew whose number was “Unknown.” We were living apart because of his corporate job that had transferred him yet again, this time back to Stuttgart, Germany, where I had lived with him before but I’d refused to live there again. Marcus wasn’t in Germany now. He was in Portland, Oregon, taking a three-week vacation that was originally supposed to include coming to see me in Texas. But then I told him not to come. Oh, and then, after telling him not to come, I added, “As long as you’re going to be in the States, this would be a convenient time for us to get a divorce.”

I didn’t want a divorce. I just wanted him to stop working at his job so much and work more at our marriage. I wanted him to spend less energy at his office so he would have some left for me when he got home. I still loved him, we still talked every single day, and I always, always, always took his calls. Especially ever since we’d had the conversation where I let it slip that there had been a few times when I hadn’t picked up the phone when he called.

“Only when I’m writing and trying to concentrate,” I assured him. His feelings were so hurt I never had the heart to ignore a call from him again. But with my heart racing, my muscles weak and now my head aching badly, I didn’t feel up to talking to him or to anybody, so I let the call go to voice mail. It was just over two hours since I’d returned from my walk.

Twenty minutes later, I figured that if perhaps I wasn’t going to die, I should at least get my ass out of bed and go see a doctor. Terlingua, a ghost town with a population of 200, didn’t have a doctor per se, but there was a physician’s assistant at a local resort who might be able to diagnose what was wrong. Before I called him, I checked my voice mail.

The message wasn’t from Marcus.

If I could turn back the clock, if I could hit the reset button, if I could change the course of history and the unfolding of events, I would. I’d gladly sell my soul to go back in time to a date three and a half months earlier, the first week of May 2009—May 5, to be precise, our final day together—and start over from there. I was in Portland for a reunion with Marcus, who was about to begin a new one-year contract in Germany. It was the same day I got laid off from the job I had in Los Angeles, the one that I used as my excuse to leave Mexico, where Marcus had been posted for the past ten months. I had tried to be a good wife by following him to Mexico, after having followed him to Germany for almost three years and then to Portland for nearly two.

“Good wife” wasn’t a role that came naturally to me and I lasted five months with Marcus in Mexico, where I spent too many long and lonely days in our house on the pecan farm before I reached my breaking point. So I took a position as U.S. Director for a London-based speakers’ bureau, for which I would book famous people for public-speaking gigs at a rate of 120 grand for one hour of their time. The height of a tanking economy ensured I wouldn’t succeed, not when company meetings were the first budget items to get cut. No meetings, no guest speakers. Thus, six months later, the phone call from my boss in London with news of my termination came as no surprise. I’ve been fired from many jobs (let’s just say I’m a little too entrepreneurial in spirit to be employable) and I’ve never mourned the loss of anything that confined me to a cubicle in an office with sealed windows. I never looked back, because I always saw endings—fixable endings such as these, anyway—as opportunities for something new, something better. In this case, I used the free time and severance pay to travel to Texas to rent the miner’s cabin for the summer so I could write about quitting one of those cubicle-confining jobs to become a pie baker.

So during this first week of May, between the ending of Marcus’s Mexico assignment and the beginning of his new one-year contract in Germany, and coinciding with the termination of my L.A. job, we met up in Portland. Portland had been our home for almost two years, it’s where we still had a lot of friends, a houseful of furniture in storage and where his company’s North American headquarters was located. We spent four honeymoon-like days together, eating at our favorite French, Italian and Thai cafés, getting massages, drinking lattes at the hipster coffeehouses, having dinner with other couples and holding hands a lot.

We agreed we could manage the long distance with me in L.A. and him in Germany and still keep our marriage intact. We had done it before; we could do it again. We would see each other once a month and it would be a win-win, because he could continue his steady career climb, and I could avoid being a stay-at-home nag. After one year he would either find another position back in the U.S. or find a different kind of work altogether.

Our whole existence—all seven and a half years of it—was like that. It was about international airports, romantic hellos and tearful goodbyes, about job changes and job transfers. When asked what the biggest challenge of our marriage was, he would say, “Logistics.” (Though he used to say it was my lack of concern for stability, for things like health insurance and a retirement plan.) I would say the biggest obstacle was his job.

“My job provides a roof over your head,” he liked to remind me. “And health insurance.”

“I didn’t marry you so you could be my provider,” I argued. “I married you because I wanted a partner who would want to spend time together, do things together, participate in the marriage and not expect me to be the one to do all the housework while you go off to work like we’re some 1950s couple.”

“I’ll pitch in more when I’m not so busy,” he insisted. “And when you get a job.”

This made no sense to me, as there would never be an occasion when his work didn’t demand so much of his time. (In fact, it would only get worse.) And besides, as a freelancer, I wasn’t really looking for a job per se. My projects, which provided decent income, came and went, but in a “feast or famine” way—not the German way. Not the steadfast, loyal “Employee for Life” way that Germans revered.

I retaliated by applying for and getting full-time jobs. And since the only career-type work I could find was back in the U.S., I was the one being driven to the airport. This usually resulted in me getting fired and running back to my safety net, my rock, my man. I ran away, but I always came back. But once I got back, it was never long before I again faced the reality—and loneliness—of a mostly empty house and a life that was about dishes, laundry and shopping—and waiting for Marcus to come home.

His job demanded long hours, which he willingly gave, which inevitably drove me to look for something else to do. I needed to keep my brain busy, needed friends, needed to keep from getting angry with him for having moved my life halfway across the world only to feel so alone. Ironically, the only solution I could find meant living apart. It wasn’t what I wanted. I just wanted more time with him. Even if he couldn’t give me that time, I wanted him to at least acknowledge how his schedule was affecting our relationship, affecting me. I wanted him to apologize when he came home three hours later than he said he would be. Just a little “I’m sorry I was late” would have been enough. I wanted him to tell me he missed me when he was gone all day. But he said nothing. Instead, he accepted—or at least tolerated—the situation in stoic silence.

And so it went. I felt hurt, I left, I returned for happy, passion-filled reunions, the loneliness gradually set in and the cycle started all over again. It was a pattern we couldn’t seem to break.

At the end of our long weekend, Marcus drove me to the Portland airport so I could return to L.A.; he was flying to Germany the next day. I stood there in his arms, at the curbside drop-off, on a rare rainless Pacific Northwest morning, while the engine of his rented Subaru Forester idled.

Marcus’s brown hair was flattened under a tight wool cap, making his high cheekbones look even more pronounced and his almond-shaped green eyes appear even deeper. He wore a brown fleece pullover and Diesel jeans with clogs. He was secure in himself and, being European, his range of style went miles beyond an American baseball hat and sneakers. Clogs had become his signature footwear. They suited him in that ruggedly handsome way, though he could as easily transform from rugged to pure elegance and sophistication when dressed for work in his hand-tailored wool suits.

My head rested against his broad chest and I felt his breath on my neck. I breathed in his clean scent and felt his soft lips on my skin as his arms pulled me closer. “Have a safe trip, my love,” he said, in the British-German accent that I never tired of. The way he talked was so soothing, even when speaking his mother tongue, that more than once I made him read to me from a German washing-machine manual or DVD-player instruction book just to hear his sexy voice.

“And you have a safe flight to Germany,” I replied. “Let’s Skype later.” We parted with a tender kiss, our mouths touching lightly in a sort of half French kiss, until I felt self-conscious about people in the cars behind us watching and pulled away. He stayed by the car and waved until I disappeared through the revolving door. I looked back through the glass window and watched him get into his rented Subaru.

And that’s the last time I ever saw him alive.

CHAPTER 2

Three and a half months later on August 19, 2009, in Terlingua, Texas, I thought I was dying of a heart attack. I didn’t answer my phone because I didn’t have the energy to lift my head off the pillow. At 11:05 a.m., I finally checked my voice mail.

The message was from a man named Tom Chapelle, who apologized for having to call, but he didn’t have my address. Why would he need my address? Why would he need to come to my house? Hell, he would have a hard time getting to my house, seeing as I was a five-hour drive from the nearest airport in El Paso, a 90-minute drive from the nearest grocery store and I lived on a dirt road with a name not recognized by the post office.

In his message, Mr. Chapelle said he was a medical examiner and he was calling because I was listed as the emergency contact for a Marcus Iken. He used the article “a” as if my husband were an object. A car. A watch. A book. A husband. I clearly don’t watch enough television as I didn’t have the slightest clue what a medical examiner was. I scribbled down the phone number he left and my heart, which had finally slowed a little, revved right up again, double time. My hands shook as I punched the numbers into my BlackBerry.

I might not have known what a medical examiner’s job was, but instinctively I knew the call wasn’t good. Worst case, I was thinking Marcus might have been injured in a car accident. He was simply in the emergency room, waiting for a broken bone to be set. Or he had fallen off his bike and needed stitches in his head, and was unable to call me himself. During his vacation, he’d been riding his road bike a lot, going on thirty-mile outings. Surely it must have been something to do with his bike and he was going to recover from whatever injury he had suffered. He was going to be fine. I didn’t know that the job title “medical examiner” could mean only one thing.

In May, after I lost my job and Marcus flew off to Germany and I left Los Angeles for Texas, I prepared for my twenty-hour drive from L.A. to Terlingua by going to the library to check out some books on tape. Since I arrived at the Venice Beach branch five minutes before closing, I had to be quick, which meant I wasn’t able to be terribly selective. I just grabbed an armful of CDs with authors’ names I recognized. Among the titles I checked out was Joan Didion’s, The Year of Magical Thinking. I listened to it in its entirety as I drove through the tire-melting temperatures and endless shades of red-and-brown landscape, crossing Arizona and New Mexico, until I finally reached West Texas.

I couldn’t stand the reader’s voice, an affected British actress, who made poor old Ms. Didion sound like a spoiled snob instead of the devastated widow that she was. A widow. A grieving widow. The book was interesting, but it wasn’t anything I could relate to. I hadn’t lost my husband. My husband was young and fit. I hadn’t lost anyone close to me, except for my grandparents who’d lived well into their eighties when their aged bodies finally wore out. Death was not a subject on my radar. Still, I listened and the book’s opening lines stuck with me the way pie filling sticks to the bottom of an oven. “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

I stood in the living room, next to my writing desk, my hand placed on the desktop to steady myself as the medical examiner’s phone rang. He picked up after two rings and I started shaking even more. “What is your relationship to Marcus?” Mr. Chapelle asked first.

“I’m his wife,” I answered. And I was. Barely. I’d asked for a divorce and pushed Marcus into starting the proceedings. We were working through a mediator in Portland who was drawing up the papers. I didn’t want a divorce. I wanted him to fight for me, for him to say, “No! You are the love of my life and I can’t live without you. I want to stay married.”

In my perfect world, he would have also said, “I promise to work less, worship you more and, above all, be on time.” He would have said, should have said—oh, why didn’t he say it—“My love, if you say you’re going to have dinner ready at seven-thirty, by God, I’ll be home at seven-thirty. I’ll even come home at seven, so I can make love to you first.”

Had it really come down to his long work hours and lack of punctuality? We had been married a few days shy of six years. That’s six years of cold dinners and hurt feelings. Six years of moving from country to country, continent to continent. Setting up a new house with each move; taking German lessons and then Spanish lessons; making new friends; saying goodbye to those friends and then making new ones again. Six years of trying to get Marcus to acknowledge me, what I needed, how much I wanted our marriage to come first and how his work, his schedule, his priorities were wearing me down.

Before we got married, during our year-and-a-half-long courtship, the majority of time I spent with Marcus was when he was on vacation. Europeans get six weeks of holidays, which meant six weeks with Marcus in laid-back mode, Marcus wearing jeans and reading books, not donning a suit, not checking his email, not coming home late. He cooked for me. He grilled steaks and shucked oysters. He did my laundry. He washed the dishes. And he made love to me for hours. It’s no wonder I wanted to marry him!

But that was on my home turf. When I moved to Germany, everything changed—Marcus changed. When he put on his suit and tie, he became a different person.

“What about me?” I pleaded time and again. “Our marriage centers only on you and your job, your promotion, your schedule. What about my career and my happiness? What about where I want to live? Why can’t we pick a place we both want to live, a place where I can speak the language and not feel so lonely, and just move there and we can both get jobs?”

We eventually moved to Portland and that helped for the year and a half we lived there. But then Marcus, thanks to his steady corporate executive career climb, got transferred to Mexico and we were right back where we started. My unanswered questions inevitably escalated into louder cries, harsher words. “I want to be in an equal partnership. Instead I feel like you just expect me to serve you!” I shouted. “I have a life, too!”

I had a life, all right. And now he didn’t.

Joan Didion’s suggestion that “life changes in the instant” might have been true for her. She was physically there in the room when her husband’s heart stopped and caused him to fall out of the chair and hit his head on the corner of the table on the way down. She saw him lying on the floor, unresponsive, his head bleeding. She had proof, evidence, visual aids. She could put her fingers on his pulse and feel he didn’t have one. She could blow air into his lungs and watch his chest rise. She could call 911 and watch the paramedics as they stormed into her apartment and hooked up their electrodes and squeezed their syringes. Being there, in person, absorbing the immediacy of the action, then yes, time must have felt compressed into an instant.