Полная версия:

Marlborough: Britain’s Greatest General

MARLBOROUGH

England’s Fragile Genius

RICHARD HOLMES

DEDICATION

I am so entirely yours, that if I might have all the world given me, I could not be happy but in your love.

The Hague, 20 April 1703/Ropley, 20 February 2008

EPIGRAPH

Our horsemen had now the better of the fight; but soon we beheld fresh bodies of horsemen, hastening to the relief of their half-defeated squadrons. Marlborough was at the head of this reserve of cavalry … I can still see him as, undaunted and serene, he rode forward amid the cheers of his troops, shouting ‘Corporal John’, the name they had given their hero; he was surrounded by his staff, evidently receiving his commands. I fell on his men with my whole regiment; he narrowly escaped being made prisoner – oh! That heaven was so unpropitious to France – but he was extricated, and my troopers were compelled to retreat.

COLONEL GERALD O’CONNOR, commanding anIrish regiment in French service, Ramillies, 1706

This is a world that is subject to frequent revolutions

SARAH DUCHESS OF MARLBOROUGH

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

THE CHURCHILLS

INTRODUCTION: Portrait of an Age

Marlborough and the Weight of History

Portraits in a Gallery

Century of Revolution

Influence and Interest

Whig and Tory

1. Young Cavalier

Faithful but Unfortunate

The King Comes Home in Peace Again

The Army of Charles II

Court and Garrison

To the Tuck of Drum

My Lady Castlemaine

The Dutch War

The Imminent Deadly Breach

The Handsome Englishman

2. From Court to Coup

Love and Colonel Churchill

Politics, Foreign and Domestic

Domestic Bliss, Public Prosperity

Monmouth’s Rebellion

Uneasy Lies the Head

3. The Protestant Wind

Settling the Crown

Little Victory

Court and Country

Irish Interlude

Fall and Rise

4. A Full Gale of Favour

Gentlemen of the Staff

First Campaign

Empty Elevation

The 1703 Campaign

5. High Germany

Forging a Strategy

The Scarlet Caterpillar

Being Strongly Entrenched: The Schellenberg

The Harrowing of Bavaria

A Glorious Victory: Blenheim

6. The Lines of Brabant

Ripples of Victory

Hark Now the Drums Beat up Again

Happy and Glorious: Ramillies

7. The Equipoise of Fortune

Favourites, Bishops and the Union

A Sterile Campaign

Politics and Plans

The Campaign of 1708

The Devil Must have Carried Them: Oudenarde

In the Galley

8. Decline, Fall and Resurrection

Failed Peace, Thwarted Ambition

A Very Murdering Battle: Malplaquet

Failed Peace and Falling Government

Last Campaigns

Dismissed the Service

Exile and Return

NOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PRAISE

OTHER WORKS

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

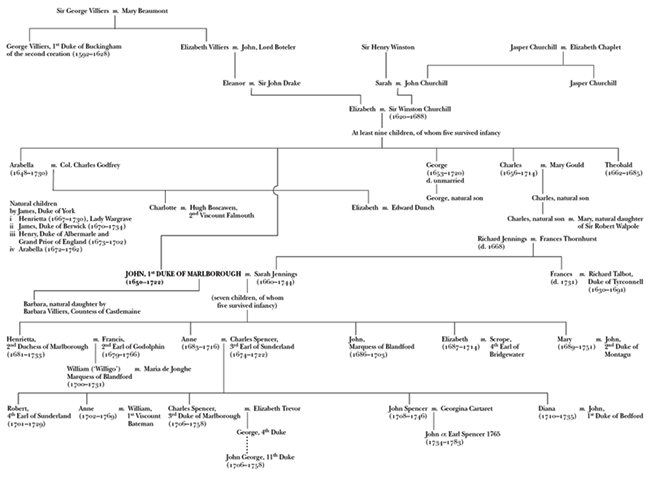

THE CHURCHILLS

INTRODUCTION

Portrait of an Age

Marlborough and the Weight of History

Some will tell you that John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was Britain’s greatest ever general. John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft, two wise judges, affirmed that:

There was no talent for war which he did not possess. He had imagination and command of detail to plan a grand strategy: he was an able generalissimo of allied armies, always ready to flatter a foreign ruler for some political advantage. His capacity for innovation really lay off the battlefield … But his greatest strength lay in his attention to the economic underpinning of the war, and in his concern for the morale and welfare of his men … In this combination of military virtues Marlborough’s greatness nestled, but most of all in his understanding that the army was precious and that its value resided in the officers and men who made it up.1

Winston S. Churchill concluded his six-volume biography of his distinguished ancestor by declaring:

He had consolidated all that England had gained by the Revolution of 1688 and the achievements of William III. By his invincible genius in war and his scarcely less admirable qualities of wisdom and management he had completed that glorious process that carried England from her dependency upon France under Charles II to ten years’ leadership of Europe … He had proved himself the ‘good Englishman’ he aspired to be, and History may declare that if he had had more power his country would have had more strength and happiness, and Europe a surer progress.2

Another assessment added private virtue to public achievement to make Marlborough the very model of the Christian soldier:

He was by nature pure and temperate, kind and brave. He had supreme genius, personal beauty, and the art of pleasing. He was born to shine in courts, and understood the graces of life to perfection. He met with glory and ingratitude, infamy and fame. So, moving splendidly through a splendid world, he saw more fully to the share of most men, of human nature and the human lot.

He was honourable in his public life because he was also honourable in his private life. He was kind and chivalrous abroad, because he was kind and chivalrous at heart, and in his own home, and to his best beloved. He had a deep, strong faith, which never failed him.3

Marlborough’s contemporary, Archdeacon William Coxe, concluded his three-volume biography, which still repays study, with the lapidary declaration that he was simply: ‘THE GREATEST GENERAL AND … THE GREATEST MINISTER that our country, or any other, has produced.’4

In his multi-volume history of the British army published in 1910, Sir John Fortescue, never a man to shy from a harsh verdict when he thought it justified, wrote of how Marlborough’s

transcendent ability as a general, a statesman, a diplomatist and an administrator, guided not only England but Europe through the War of Spanish Succession, and delivered them safe for a whole generation from the craft and ambition of France …

Regarding him as a general, his fame is assured as one of the greatest captains of all time; and it would not become a civilian to add a word to the eulogy of great soldiers who alone can comprehend the full measure of his greatness.5

Fortescue wrote that Marlborough, like Wellington,

was endowed with a strong common sense that in itself amounted to genius, and possessed in the most trying moments a serenity and calm that was almost miraculous … With such a temperament there was a bond of humanity between him and his men that was lacking in Wellington. Great as Wellington was, the Iron Duke’s army could never have nicknamed him the Old Corporal.6

Elsewhere, citing an approving comment in the papers of an officer in Marlborough’s army, Fortescue mused: ‘What modern decoration (save the Victoria Cross) could compare to a word of hearty praise from Corporal John himself?’7

However, it was hard even for Fortescue to ignore the fact that Marlborough had detractors during his lifetime, though he maintained that the duke’s ‘fall was brought about by a faction, and his fame has remained ever since prey to the tender mercies of a faction’.8 Some of Marlborough’s warmest admirers acknowledge that there was indeed another side to the man. Although Charles Spencer, like Winston S. Churchill, has some of Marlborough’s blood in his veins, he is a wise enough historian to admit that:

It is difficult to understand Marlborough the man. He was enigmatic, focussed, and brilliant. He was also avaricious and – as we know from his correspondence with the Jacobites – capable of double-dealing. However, his men adored him, and they knew his incomparable military worth: they were proud to point out that he never lost a battle, or failed to take a city that he besieged.9

Marlborough’s abandonment of James II (who had befriended him and raised him to the peerage) in 1688 was a move so significant that one historian has called it ‘Lord Churchill’s coup’. It led G.K. Chesterton to accuse him of the vilest of betrayals: ‘Churchill, as if to add something ideal to his imitation of Iscariot, went to James with wanton professions of love and loyalty, went forth in arms as if to defend the country from invasion, and then calmly handed over the country to the invader.’10 Marlborough lived on the margins of treason. He never regarded the verdict of 1688 as final, and remained in touch with the Jacobite court for the rest of his life, a process assisted by the fact that one of James’s illegitimate sons, James FitzJames, Duke of Berwick, was both Marlborough’s nephew and a marshal of France.

Although the circumstances of his upbringing go far towards explaining his notorious cupidity, Marlborough was given to a rapacity remarkable even in a rapacious age, amassing offices which made him one of the richest men in the land. While we must accept stories about his tight-fistedness with caution, for they were circulated by his detractors to damage his reputation, the tale that, after an evening’s gaming in Bath, he borrowed the money for a sedan chair but then walked home regardless may indeed be well-founded. Yet he spent enormous sums on building Blenheim Palace, which still glares out in chilly splendour as his lasting memorial. Though most of the practical work of supervising its construction was left to his wife, who demonstrated that high temper rarely makes a successful contribution to labour relations on a building site, the concept was his, and his pressing on with its construction at a time of crisis in the nation’s history showed that selective blindness which sometimes afflicts the great.

Many of Marlborough’s advocates argue that, great though his achievements were, he would have been even more successful had he not been ‘hampered by the intransigence of the Dutch field-deputies, incompetent civilians attached to the Duke’s staff whose agreement in any project had to be obtained before it could proceed’.11 There is a strongly nationalistic element in much that is written about Marlborough, and in this instance it is worth recalling that an Allied military defeat in Flanders risked having far more effect upon the Dutch than upon the English, conveniently insulated from the armies of Louis XIV by Shakespeare’s ‘moat defensive’. When Marlborough clashed with the Dutch, as he did from time to time, he was not always right and they were not always wrong, and there were times when he avoided the complicating longueurs of coalition politics by outright deception.

One of the pleasures of the research for this book is that it took me back to G.M. Trevelyan’s incomparable trilogy on the reign of Queen Anne. If earnest modern scholars have unearthed evidence which changes some of Trevelyan’s findings, few have his ability to bring an age to life. He concluded his assessment of Marlborough’s personality by speculating that:

Perhaps the secret of Marlborough’s character is that there is no secret. Abnormal only in his genius, he may have been guided by motives very much like those that sway commoner folk. He loved his wife, with her witty talk and her masterful temper, which he was man enough to hold in check without quarrelling. He loved his country; he was attached to her religion and free institutions. He loved money, in which he was not singular. He loved, as every true man must, to use his peculiar talents to their full; and as in his case they required a vast field for their full exercise, he was therefore ambitious. Last, but not least, he loved his fellow men, if scrupulous humaneness and consideration for others are signs of loving one’s fellows. He was the prince of courtesy.12

In all this, though, Trevelyan recognised that he was taking issue with his distinguished uncle, whose surname he bore as his own middle name. Thomas Babington Macaulay was a poet (who, if he had never written another word, would surely be remembered for his account of Horatius holding that bridge), politician and the dominant British historian in the mid-Victorian era. Macaulay, argued Trevelyan, ‘adopted his unfavourable reading of Marlborough’s motives and character straight from Swift and the Tory pamphleteers of the latter part of Anne’s reign’. Yet he was

less often misled by traditional Whig views than by his own overconfident, lucid mentality, which always saw things in black and white, but never in grey … He instinctively desired to make Marlborough’s genius stand out bright against the background of his villainy.13

The villainy, maintained Macaulay, was certainly dark enough. Marlborough was wholly immoral. He ‘owed his rise to his sister’s shame’, and was then ‘kept by the most profane, impious and shameless of harlots’, Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine. He was woefully ignorant, and ‘could not spell the most common words in his own language’. His avarice knew no bounds, and ‘though he drew a large allowance under pretence of keeping a public table, he never asked an officer to dinner’. And he was, quite simply, a traitor, rendering ‘wicked and shameful service to the Jacobite cause’ by leaking information of a 1694 expedition against Brest so that its troops were slaughtered and its commander, a personal rival, was slain.14

This is not the moment to deal with Macaulay’s charges in detail, although it is clear that the documents he used to formulate some of them do, in themselves, demonstrate their own falsehood, thereby making Churchill’s accusation of ‘liar’ more appropriate than Trevelyan’s defence of his forebear as an honest historian misled by his emotions and his sources. ‘Lord Macaulay is not to be trusted either to narrate facts accurately, to state facts truly, or to answer the judgement of history with impartiality,’ wrote a barrister who applied his forensic skills to Macaulay’s methods, and it is impossible for a modern historian to disagree.15

Even though Macaulay erred in his attacks on Marlborough, it is already evident that there is much more to the man than stout hagiography can possibly acknowledge. We might avoid at least part of the problem by concentrating on the military aspects of his career, and by passing rapidly over his early life to see him emerge, full-fledged, as captain general of the English army in the Low Countries. Indeed, David Chandler, one the most gifted historians to write about Marlborough in recent times, sidestepped the issue in his Marlborough as a Military Commander by considering the duke in his role as a general, although there are few men less suited to the description ‘simple soldier’.16 To consider Marlborough purely as a general is as misleading as it would be to see, say, Paul McCartney as only a classical composer, Alexander Borodin as just a chemist, or Winston S. Churchill as a simple historian.

Part of my task, then, is to get as close as I can to the man that Churchill loved to call ‘Duke John’. However, almost like hunted game that knows its tracks will be followed, Marlborough himself made my task no easier. Although the shelves of the British Library groan beneath the weight of the Blenheim Papers, with thousands of letters showing him in a variety of lights, as husband, lover, courtier, politician, alliance manager, diplomat, commander-in-chief, prosecutor, defendant and even interior designer, he rarely let his mask slip. Wellington is the general to whom he is most often compared, and is the only other British commander who has ever exercised command on sufficient scale, for long enough and in varied enough circumstances for him also to be considered a truly great general. Yet despite his notorious secretiveness, in his later years Wellington was always prepared to unburden himself to friends or diarists. There was generally an answer to those questions that began, ‘Tell me, Duke …’ and the Wellington of old age tells us, across the nuts and port, about the commander of his youth and middle years. It is just possible that Marlborough might have done the same had he enjoyed a long retirement, marching slowly to meet a slothful death. But even then I doubt it: he was too mindful of those necessary treasons of his early life, too well aware that he had been all things to most men, to let us inside his mind.

Many of my sources will be familiar to those who know the period. I have made extensive use of the duke’s own words, going back to the originals in the British Library when I have had to, but also availing myself of Sir George Murray’s five-volume edition of Marlborough’s dispatches and Henry L. Snyder’s three volumes of the Marlborough – Godolphin correspondence. Both Marlborough’s quartermaster general (chief of staff by modern standards), William Cadogan, and his private secretary, Adam de Cardonnel, have left papers which throw useful light on the way that Marlborough’s headquarters worked. Viscount Chelsea, heir to the present Earl Cadogan, recently discovered some of his ancestor’s papers, and through his kindness I am, I believe, the second historian to consult them. They show just how much routine work Marlborough entrusted to Cadogan, and give early grounds for suspecting that even if command is, in a legal and spiritual sense, indivisible, it is harder than we once thought to see just where Marlborough ended and Cadogan began.

Marlborough’s own hold on political power would scarcely have been possible without his wife’s intimate relationship with Queen Anne. Sarah Marlborough is rarely much further away from these pages than she was from her husband’s thoughts. I have not only used her correspondence, but a good deal of her self-justifying pamphleteering, much of it produced with the aid of collaborators like Bishop Gilbert Burnet, who generally strove to be objective, and her man of affairs, Arthur Maynwaring, who did not. While no assessment of the politics of the age could be complete without taking the duchess’s views into account, her words require more caveats than most. Here she is on the subject of Queen Anne, with whom she had once enjoyed a friendship so very close that some writers have detected lesbianism.

Queen Anne had a person and appearance not at all ungraceful, till she grew exceeding gross and corpulent. There was something of majesty in her look, but mixed with a sullen and constant frown, that plainly betrayed a gloomy soul, and a cloudiness of disposition within. She seemed to inherit a good deal of her father’s moroseness, which naturally produced in her the same sort of stubborn positiveness in many cases … as well as the same sort of bigotry in religion.

Her memory was exceeding great, almost to wonder, and … she could, whenever she pleased, forget what others would have thought themselves obliged by truth and honour to remember, and remember all such things as others would think it an happiness to forget. Indeed she chose to retain in it very little besides ceremonies and customs of courts … so that her conversation, which otherwise might have been enlivened by so great a memory, was only made more empty and trifling but is chiefly turning upon fashions and rules of precedence, or observations upon the weather, or some such poor topics, without any variety of entertainment.17

There are two points of which I have no doubt whatsoever. The first is that the Marlboroughs’ relationship, despite its stormy moments, was a genuine love-match. The second is that if there is indeed an afterlife I must look out for squalls soon after crossing the bar, for Sarah was as jealous of her lord’s memory as of her own historical reputation.

No student of the period can be unaware of the fact that there are far fewer letter-writers and diarists on hand to describe the War of Spanish Succession than there would be, a century later, to tell us about the Peninsular War. However, there are certainly enough to get us in amongst the powder-smoke. That dour Cameronian Lieutenant Colonel Blackader complains of the army’s profanity; Captain Richard Parker takes pride in watching his own Irish soldiers beat their countrymen in French service at Malplaquet; Corporal Matthew Bishop assures us, not once but several times, that Marlborough could not have won the war without him; and Brigadier General Richard Kane warns us of the perils of premature surrender – and the dangers of too resolute a defence.

John Wilson, the ‘old Flanderkin Sergeant’, recalls attacking the Schellenberg with his front-rank men clutching fascines ‘in order to break the enemy’s shot in advancing’.18 Private John Marshall Deane of the 1st Foot Guards recalls that at the same action, ‘being strongly entrenched they killed and mortified abundance of our men both officers and soldiers’.19 Chaplain Josias Sandby maintained a useful journal of the Blenheim campaign, often attributed to Marlborough’s chaplain-general Francis Hare. Chaplain Samuel Noyes wrote assiduously to his bishop, hoping no doubt that civil preferment might follow military accomplishment.20

On the French side, the Duke of Berwick, illegitimate son of James II by Marlborough’s sister Arabella Churchill and probably the most competent of the later Stuarts, published a set of memoirs before he was killed in action. Colonel François de la Colonie commanded a Bavarian grenadier battalion composed of French deserters, and escaped from the storming of the Schellenberg with his coat scorched by musket-fire and his long riding-boots jettisoned to run the better. The Count de Mérode-Westerloo, in the perplexing way of the age a Flemish nobleman but a loyal officer in the army of Louis XIV, tells us what it was like to wake up at Blenheim to see the Allies advancing steadily on the French camp but to find everyone else asleep. Marshal Camille de Tallard, the French commander that day, has left us his own account of the action. He told the French minister of war that he had had a bad campaign plan foisted upon him, and found it impossible to get on with his allies: ‘it is a fine lesson that we should only have one man commanding an army, and that it is a great misfortune to have to deal with a prince of the humour of M. the Elector of Bavaria …’ Having been traduced by his senior colleagues, Tallard tells us that he was then let down by his men: ‘The bulk of the cavalry did badly, I say very badly, for they did not break a single enemy squadron.’21 Sadly, his subordinates did not share his view. Another of those accounts whose writer lamented that his own courage and prescience were not matched elsewhere concluded: ‘You know, Sir, better than me whose fault this is.’22