скачать книгу бесплатно

The last thing I want to do is criticize Olly, not when he’s being so lovely and so helpful, but he and Jesse are taking a bloody long time to start getting this furniture in, aren’t they? I mean, seriously, it’s only a small armchair, a coffee table and a three-drawer plywood chest. If it weren’t for the bulk, I’m sure I’d be able to bring them up by myself.

Still, at least I’ve had the time to get all these boxes up, and I ought to be able to find the glasses in one of them. This one, most likely, that I’ve labelled NESPRESSO MACHINE AND MISC: sounds like it’s where I might have packed my kitchen bits and bobs. I open it up just as I hear a rather out-of-breath voice behind me.

‘I’m telling you, Lib. This isn’t going to fit.’

It’s Olly, who’s coming through the doorway. He’s purple in the face with exertion, his shoulders are straining underneath his T-shirt, and he’s gripping one end of the most enormous sofa I’ve ever seen.

Not only enormous, in fact, but upholstered in some truly terrible apricot-hued rose-patterned fabric that makes it look like a bomb has gone off in the world’s most twee garden centre.

‘Well, it might technically fit,’ an equally purple-faced Jesse grunts, inching through the door with the other end of the sofa, ‘but there’s not going to be much room for anything else.’

‘But this isn’t the sofa I put aside!’

‘What do you mean?’ Olly cranes his head round to look at me.

‘I mean, this isn’t the sofa I put aside! I didn’t put aside a sofa at all, in fact! It was meant to be a leather armchair.’

‘Well, this is the stuff Uncle Brian told us you’d chosen.’

Uncle Brian has made, it appears, a terrible, terrible error.

‘And there isn’t a leather armchair in the van,’ Olly adds. ‘There’s this sofa, and the oak blanket box, and the big mahogany chest of drawers, and …’

‘But I didn’t choose any of those things either! I chose an armchair, and a little walnut coffee table, and a small chest for my clothes.’

‘Walnut coffee table?’ Olly turns back to Jesse. ‘Hang on – where have I seen a walnut coffee table recently?’

‘There was one in the stuff we dropped off with your mum last night, for the Woking Players,’ Jesse says, scratching his head in a manner that suggests he’s not quite cottoned on to what’s happened.

Whereas it’s becoming fairly clear to me that the Woking Players are getting my furniture, and that I am getting the Woking Players’ set-dressing for whatever Noël Coward play or Stephen Sondheim musical they’re performing for the next couple of weeks.

‘I’m really sorry, Lib.’ Olly bends his knees to lower the sofa to the floor, and indicates that Jesse should do the same. I can hardly blame them; it must weigh a tonne. ‘Do you want us just to take it back to the van?’

‘Yes … well, no … I mean, did you bring that futon you mentioned?’

‘Futon …’ Olly looks blank-eyed for a moment, until recognition dawns. He slaps a hand to his head. ‘Shit. I forgot about that.’

‘It’s all right. But you’d better leave the sofa here. I’ve not got anything else to sleep on.’

‘Are you sure? I mean, apart from anything else, it’s a bit … well, up close, it’s pretty pongy.’

‘Sort of—’ Jesse leans down and inhales one of the overstuffed cushions – ‘doggy-smelling.’

He’s right, in one sense: the smell coming up out of the sofa cushions, now that they mention it, is distinctly doggy. More specifically, the smell of a dog that’s been out in the rain all morning and is now drying by a warm radiator, whilst letting out the occasional contented fart. Quite a lot like Olly and Nora’s ancient Labrador, Tilly, who farted her way to the grand old age of seventeen; she died five or six years ago but I can still remember her musty pong. Not to mention that there are deep grooves scratched into the wooden part of the arm on one side, as if the rain-dampened dog had a good old go with its claws on there before heading off to dry.

I stare up at Olly, despair taking hold. ‘Did you really think this was the sofa I’d chosen? You didn’t stop to question it at any point?’

‘Well, I don’t know your precise taste in soft furnishings!’ Olly says, indignantly. ‘You make vintage-style jewellery. I thought maybe you wanted a vintage-style living room.’

‘This sofa isn’t vintage style, it’s …’ I glower down at the sofa, blaming it, in all its apricot-hued vileness, for everything that’s gone wrong for me today.

I mean, let’s not beat around the bush: it’s been a torrent of crap ever since I got out of bed this morning. Losing half my hair, losing my job, getting short-changed out of a proper flat, Cass riding off into the sunset with Dillon …

‘I’m sorry,’ I say, plopping myself down, wearily, on the sofa, whereupon a cloud of doggy-smelling dust billows out. It actually makes my eyes water, which obviously makes it look like I’m crying. The irony being that, actually, that’s exactly what I feel like doing. If it were just Olly here, and not Jesse, whom I barely know, I’d probably be bawling my eyes out right now. ‘You’ve been so lovely,’ I sniff. ‘You, too, Jesse, for lugging the bloody thing all the way up here. I’m sorry.’

There’s a short, slightly awkward silence, ended by Olly folding his six-foot-three bulk onto the cushion next to me and putting a brotherly arm around my shoulders.

‘Look, Lib. Why don’t we leave the rest of the furniture in the van to take away with us, and then go and find your new local? Save you worrying about wine glasses.’

Much as a drink at the pub – even the inauspicious surroundings of the dodgy-looking one (no doubt owned by Bogdan) down the road – would probably do me good right now, I just don’t have any energy left to make a positive out of the evening. Honestly, all I want to do right now is stick to Plan A: dig my pyjamas out of one of the boxes, pop open the champagne so I can scoff the lot myself without having to worry about finding any glasses, and – oh, heavenly bliss, after the day I’ve endured – curl up in front of Breakfast at Tiffany’s (or Tea at Tesco’s as Olly calls it, in honour of our first meeting)on my iPad.

‘Thanks, Olly, but I’m really tired. I think the best thing is to get an early night.’

‘Ooops, sorry.’ Jesse makes a beeline in the direction of the front door. ‘You don’t want a third wheel around at this time of night. I’ll leave you two to it.’

‘Us two?’ I blink up at him. ‘God, no, no, me and Olly aren’t—’

‘We’re not together, mate,’ Olly interrupts, firmly. ‘I’m fairly sure Libby meant an early night on her own.’

‘Ohhhhh … OK, I just thought … still, I’ll be on my way, anyway.’

‘Thanks again, Jesse. You really must let me buy you a drink, I’m really grateful …’

But he’s already gone.

‘Sorry about that,’ says Olly, not meeting my eye. Which is understandable, because the Mistaken Thing is rearing its mortifying head for the second time tonight – twice more than it normally does in the space of months or even years – and I know he’d like to put it back in its box as fast and definitively as possible. ‘I’m not sure where he got that idea. But in all seriousness, are you sure you’re going to be OK here tonight? I mean, you don’t even have anything to sleep on.’

‘Yes, I do. What’s the point of having a colossal sofa if it can’t double up as a bed for the night?’

‘Well, if you’re sure … look, why don’t I come over tomorrow night and help you unpack, then we can talk more about what you’re going to do next? I’ll even cook you a slap-up dinner, how about that?’

‘In this kitchen?’

‘Oh, ye of little faith. Have you forgotten that time I cooked an entire three-course meal in Nora’s student bedsit? With only a clapped-out old microwave and a single-ring electric hob?’ He casts an eye over my minuscule ‘kitchen’. ‘This is professional-standard by comparison. I’ll do you a nice roast chicken. Easy as pie. Oh, and I’ll even make a pie, come to think of it. A pie of your choosing. Lemon meringue, apple and blackberry … your pie wish is my command.’

‘That’s lovely of you, Ol, but let me cook for you, for a change. As a thank you for all your help.’

‘Er …’

‘Oh, come on! I’m not that bad a cook! I can rustle up a tasty stew.’

‘Can you?’

I give him a Look.

‘OK, OK … well, that would be lovely, if you’re sure, Libby,’ he says, looking pretty un-sure himself. ‘And I’ll bring that pie for dessert.’

‘Thank you. For everything, I mean.’

‘Any time.’ He leans over and gives me a swift – very swift – kiss on the top of my head as he gets to his feet. ‘You know that.’

I can’t help but feel a bit empty, when I’ve closed the door on him and have the flatlet to myself again.

Well, to myself and the Chesterfield.

Which, now that we’re alone together – me and the Chesterfield, that is – is just making me feel sadder than ever. I mean, look at it: after its moment of glory on screen, whenever that was, it’s done nothing but moulder away in Uncle Brian’s storeroom ever since.

‘Well,’ I say to the sofa. ‘Everything’s all turned to shit, hasn’t it?’

The sofa, unsurprisingly, has nothing to say in reply to this.

‘I mean, let’s just look at my life, shall we?’ I go on, squeezing round the sofa’s bulky back and picking up my wine bottle from the melamine counter (because if I’m starting to chat to the furniture, then I really, really must be in need of a drink). ‘Because it’s not as if things were exactly terrific this morning, before I lost my job, half of my flat and half of my hair.’ My voice has gone rather small, and very wobbly, so I’m extremely glad that I’m only talking to the sofa, even if it might also be an early sign of impending madness. I hate getting upset in front of real people. No: not just hate it: I just don’t do it. Won’t do it. Haven’t done it, I’m stupidly proud to say, since I blubbed in front of Olly and Nora the first day I met them, at the New Wimbledon Theatre, when my waster of a father cancelled my birthday plans at the last minute. ‘It’s not as if I was making a big success of myself.’

I unscrew the cap, take a large swig, and then another, and then I squeeze my way round the back of the Chesterfield so that I can plonk myself down on one of its doggy-smelling cushions. Then I reach for my bag and dig around to find my iPad. I balance it on one of the sofa’s wide arms – one thing its bulk is useful for, I suppose – and then I go to my stored movies, and tap on Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

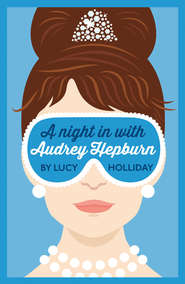

Because the only way I’m ever going to make it through tonight without drinking all this wine on my own, ordering the largest pizza I can find at Bogdan’s takeaway, scoffing down the entire lot and then – inevitably – drunk-dialling my horrible ex-boyfriend Daniel, who will be just as distantly condescending as he was for the majority of our short relationship, is if I’ve got Audrey to get me through.

I suppose it’s one (and only one) thing I have to be grateful to my father for: the movies. For the way the movies make me feel. For the rush of mingled excitement and serenity that I feel when I settle into the sofa, now, to the orchestral strains of Moon River. And look at Audrey: just look at her. Gliding onto the screen, her beautiful face impassive behind those iconic Oliver Goldsmith tortoiseshell sunglasses, her body moving with dancer’s grace in that black dress. And then there’s that offbeat pearl-and-diamanté necklace and matching tiara, which look precisely like the kind of thing a little girl would pick out of their grandmother’s jewellery box to play dressing-up with, and which – despite Dad’s irritation – were precisely the things I was most dazzled by, when I first watched the movie with him, as a nine-year-old. Those glittering jewels made me think, back then, that this otherwordly being must surely be some sort of princess, and they’ve not lost any of their magic now that I’m two decades older.

Which reminds me: Nora’s bridal necklace.

I haul myself up from the Chesterfield – no mean feat when you could lose a double-decker bus or two down the back of these cushions – and s-q-u-e-e-z-e my way back round it to get to the ‘kitchen’, where most of my boxes are sitting, waiting for me to unpack them. My bead-box will be at the top of one of them, somewhere … yep, here it is, with Nora’s necklace neatly folded inside. In my mind’s eye it was always meant to look like something Holly Golightly might window-shop on one of her jaunts to Tiffany’s, but I don’t know if it’s quite there yet. I’ve strung some gorgeous vintage beads along a plain necklace cord – mostly faux pearl, with the occasional randomly dotted silver filigree – either side of this delicate but dazzling diamanté orchid I found in a retro clothing store in Bermondsey one rainy Saturday when I’d accompanied Olly over there to a food market. The orchid was a brooch, originally, but I’ve used a brooch converter on the back pin to make it a charm suitable for a necklace. I’ve already finished it off with a silver clasp at the back, but I think I might dig out my chain-nosed pliers, remove the clasp, then really Audrey-fy the whole thing up by adding another row of pearls and random filigree beads either side of the orchid, thereby turning a pretty pendant into a dramatic layered show-stopper …

A little way behind me, somebody says, ‘Good evening.’

I spin round, wondering, for a split second, if madness really is setting in, and if – seeing as I was talking to the sofa a few moments ago – I’m starting to hear the sofa talk back to me.

But it’s not the sofa. It’s someone perched, in fact, on the arm of the sofa.

And that someone is Audrey Hepburn.

(#u3caa25fd-b5df-5df3-8efe-8a1283928b51)

OK, first things first: obviously it’s not actually Audrey Hepburn.

I mean, I may just have been chatting to my new sofa, but I’m not 100 per cent crackers, not yet. Obviously there’s no way this is the real, bona-fide, sadly long-dead Hollywood legend Audrey.

But second things second and third things third: if she’s a lookalike, she’s a bloody good one (she’s dressed exactly, but I mean, exactly the same as the Audrey Hepburn I’ve just been watching on screen: black dress, sunglasses, triple-strand pearls and all); but, more to the point, what the hell is an Audrey Hepburn lookalike doing in my flat in Colliers Wood at eight thirty on a Wednesday evening?

Before I can ask this question – while, in fact, I’m still doing a good impression of a goldfish – she gets to her feet, leans slightly over the melamine worktop and extends a gloved hand.

‘I very much hope,’ she says, ‘that I’m not barging in.’

Wow.

She’s got the voice down absolutely pat, I have to say. The elongated vowels, the crisp, elocution-perfect consonants, all adding up to that mysterious not-quite-English-not-quite-European accent. Exactly the way Audrey Hepburn sounds when you hear her in the movies.

‘But how did you get in?’ I glance over at the door, which I’m sure I locked when Olly and Jesse left. There’s no way she can have come in that way … Unless she has a key, of course … ‘Oh, God. Did Bogdan send you?’

Her eyebrows (perfectly arched and realistically thick) lift up over the top rim of her sunglasses.

‘Bogdan?’

‘The man who owns this block. Owns most of Colliers Wood, by the looks of it.’

‘Colliers Wood?’ she repeats, as though they’re words from a foreign language. ‘What a magical-sounding place!’

‘It’s really, really not.’

‘Where is it?’

‘You’re joking, right?’

She stares at me, impassively, from behind the sunglasses. (Oliver Goldsmith sunglasses, I can’t help but notice, in brown tortoiseshell, so she’s certainly done a thorough job of sourcing a fantastic replica pair from some vintage store or other. Or some shop that sells exact-replica Audrey Hepburn gear, because that necklace she’s wearing is an absolute ringer for the one the real Audrey was wearing on my iPad screen a few minutes ago.)

‘It’s in London. Zone Three. Halfway between Tooting and—’

‘How wonderful!’ She claps her hands in delight. ‘I adore London! I lived here just after the war, you know. The tiniest little flat, you wouldn’t believe how small, right in the middle of Mayfair. South Audley Street – do you know it at all?’

‘Yes. I mean, no. I know South Audley Street, but I don’t know where you … rather, where Audrey … look, I don’t mean to be rude, but you have just sort of … showed up. And I’m not sure I’m happy about other people having keys to the flat, so perhaps you could tell Bogdan …’

‘Darling, I’m awfully sorry, but I really don’t know this Bogdan fellow at all. In fact, it’s just occurred to me that you and I haven’t introduced ourselves properly! I’m Audrey.’ She extends a gracious hand, emitting a waft, as she does so, of perfume from her wrist: an oddly familiar scent of jasmine and violets. ‘Audrey Hepburn.’

‘Right,’ I snort. ‘And I’m Princess Diana.’

‘Oh, my goodness!’ She bows her head and drops into an impressively low curtsey. ‘I had no idea I was in the presence of royalty!’

‘No! I mean, obviously I’m not …’

‘I should have realized, Your Highness. I mean, only a princess would have jewels like that.’

I’m confused (make that even more confused) until I realize that I’m still holding Nora’s half-finished diamanté and pearl-bead necklace in my hand.

‘No, no, this isn’t real.’ I shove the necklace back into the bead-box. ‘And I’m not Your Highness. I’m not a princess.’

She glances up, still balanced in her curtsey. ‘But you said …’

‘Yes, because you said you were Audrey Hepburn. Now, don’t get me wrong, you’re doing a fantastic job …’

Which she really, really is, I have to admit, the longer I stare at her.

I mean, I know anyone can recreate the Breakfast at Tiffany’s look without too much trouble – the dress, the sunglasses, the beehive – but she’s really cracked the finer points, too. Her hair isn’t just beehived, it’s exactlythe right shade of chestnut brown; her lips are preciselythe right shape and fullness; her complexion is Hollywood-lustrous and oyster-pale.

Oh, and it’s just occurred to me that I can pin down that familiar jasmine-y, violet-y scent, after all: it’s L’Interdit, the Givenchy perfume created specially for Audrey Hepburn, of course. Mum and Cass gave me a bottle of it several Christmases back.

‘Does it take a really long time?’ I suddenly blurt out.

‘I beg your pardon?’