Полная версия:

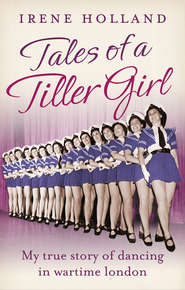

Tales of a Tiller Girl

For my lovely mum Kitty, who inspired me to achieve my dream.

And to my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, in the hope that you all find your passion in life, as I have in dancing.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

1. On Our Own

2. Bows and Bombs

3. Painful Goodbyes

4. Fairyland

5. Ballet in the Blitz

6. Treading the Boards

7. Briefly a Bluebell

8. Trying Out

9. Bright Lights

10. Sisterhood

11. Dancing with the Stars

12. Disaster Strikes

13. Making Mum Proud

14. War Wounds

15. Horror and High Tea

16. Man Trouble

17. The Final Curtain

18. New Beginnings

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Picture Section

Exclusive sample chapters

Moving Memoirs eNewsletter

Write for Us

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

On Our Own

The little girl walked down the hospital ward tightly clutching her mother’s hand. Nurses bustled up and down in their starched white uniforms and capes, and the smell of carbolic soap was overpowering. Finally they got to a bed at the end, which had the curtains drawn around it for privacy.

‘Come here, dear,’ said one of the nurses, lifting up the girl and sitting her on the bed so that she had a better view of the man lying in it.

He looked very thin and frail, and he had a nasty, hacking cough. Her mother passed the man a handkerchief, and as he patted his mouth the girl noticed bright red spots of blood splattered all over the white material.

Although just two years old, the child knew instinctively that it was serious. Maybe it was her mother’s tears that gave it away or the pale, gaunt face of the man lying in the bed. Every breath he took was so laboured and shallow and seemed to require so much effort that it almost sounded like his last.

‘Poor Daddy,’ she sighed.

You see, that little girl was me, and that was my first, last and only memory of my father, Edwin Bott.

I was born in 1930 in a nursing home on the edge of Wandsworth Common in south-west London. My brother, Raymond, was eleven years older than me and, like a lot of children, I think I was what you’d call a bit of a mistake! I was from a very musical background – my father was a cellist and my mother, Kitty, was a professional violinist. They had met in the orchestra pit while they were playing music for the silent films when Mum was seventeen and my dad was seven years older. When they first got married they lived in Oxford, and that’s where my brother was born, but then they moved up to London to play in the theatre orchestras. My father also used to play in a quartet on banana boats that would take passengers to Rio de Janeiro and bring bananas back. He would be away for weeks at a time, and the bananas he was given by the crew would be completely rotten by the time he got back home to London.

My name was Irene but everyone called me Rene. I was named after my father’s half-sister Rene Gibbons. She was a Goldwyn Girl, part of a glamorous company of female dancers employed by the famous Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn in the Twenties and Thirties to perform in his films and musicals. Many female stars got their big break in his troupes, including Lucille Ball and Betty Grable. Although I’d never met her, I’d seen from a photograph she once sent us that Rene was an incredibly beautiful woman. She looked like something from a Pre-Raphaelite painting, with her long auburn hair and huge green eyes. Unfortunately she and Mum never got along, I suspect probably due to a little bit of jealousy on my mother’s part, although she never really told me why.

‘I wanted to call you Violet,’ Mum used to say to me as I was growing up. ‘But your sneaky father went off to the town hall one day and registered your birth without me knowing.

‘When he came back and I saw the name Irene on your birth certificate there were a few fireworks, let me tell you.’

I could well imagine. My mother was only tiny but she had a sparky temper, that was for sure.

Sadly I was too young to remember Dad, apart from that one time when I had visited him in hospital. I was only two when he died of tuberculosis at the age of thirty-three. He had terrible asthma, so I think it affected him very quickly. It must have been horrible for my mother and Raymond to see him in so much pain as his lungs disintegrated and he constantly coughed up blood. There was no cure in those days and it was highly infectious. My brother and I were tested for it, but thankfully we were clear.

We’d always been comfortably off, but after my father died we were left destitute. My brother had to leave his private boarding school and it was a real struggle. Mum had a small amount from her widow’s pension so she decided to buy a 1920s house in London. But we were there less than a year as she couldn’t keep up with the mortgage payments. Eventually the house was repossessed and she lost her deposit. There were no Social Services then, and my mother couldn’t work because she had me and she’d lost all her income from Dad.

‘We’re going to have to move in with your grandmother and grandfather,’ she told me.

I was three by then and this is where most of my memories start. Her parents, Henry and Kate Livermore, lived in a large, three-storey Victorian terrace in Battersea, south-west London. We called them Gaga and Papa because my brother couldn’t say their names properly when he was little and those nicknames just stuck.

The house seemed huge to me as Raymond and I tore around it. There was a big sitting-room at the front with settees and an open fire and all this lovely antique furniture. A passageway led to a tiny scullery with a big copper pot with a fire underneath where you would boil your washing and a really tired-looking porcelain sink. There were no hot-water taps in those days, of course. Then there was a dining-room with a big range cooker that had a coal fire underneath a couple of hot plates and took hours to heat up. On the second floor there was another living-room, two bedrooms and a bathroom, and on the very top floor was a tiny, dusty attic room.

‘This is where we’ll live, children,’ Mum told me as we climbed up the steep staircase to the attic.

‘Where’s all the furniture, Mummy?’ I asked.

It was very dark and shivery cold, and there was hardly anything in it. But there was a double bed for Mum and me to share, a camp bed for Raymond and a little larder where we could keep our food.

There was only one very dim electric light up there, and one night while we were sitting there it went out. I screamed, as I was so afraid of the dark.

‘I’ll go and find out what’s happened,’ said Mum.

She went downstairs to have a look while I sat there, completely petrified. A few minutes later she came storming up the stairs holding a candle. I could tell by the look on her face that she was fuming.

‘I don’t believe it,’ she said. ‘They’ve cut us off.’

Mum hadn’t been able to afford to pay her share of money for the meter that week, so my grandparents had cut off the electricity supply to the attic. From then on, even though the lights were blazing downstairs, we had to make do with a single candle. Mum was absolutely furious.

I was too young to really understand at the time, but now looking back, no wonder. How awful to do that to their own widowed daughter at a time when she so needed their help and support. I was old enough to know it wasn’t nice, though.

‘Why are Gaga and Papa being horrid to you?’ I asked her.

‘Your grandparents didn’t like it when I married Daddy, as he believed in different things to them,’ she explained.

My grandparents were right-wing Conservatives and extremely religious, which was the norm in those days, while my father was the complete opposite. He was a very left-wing socialist and an atheist. In fact, when he died he insisted that there was no funeral or flowers and he was buried in an unmarked grave somewhere in London. He used to speak at Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park and was one of the founder members of the Socialist Party of Great Britain. When he and my mother had gone off to the register office to get married in secret when she was eighteen, Mum’s family had practically disowned her.

‘But I loved your father and it doesn’t matter what they think,’ said Mum, giving me a kiss on the forehead.

I could see she was holding back the tears but I never once saw her cry in front of me. She was very loving, and was always kissing and cuddling me. I think in a way she needed me as much as I needed her.

My mother was a very proud person, so I could tell it was humiliating for her to have to go cap in hand to her parents and to have absolutely nothing.

One morning she was busy cleaning and tidying up our room.

‘I’m getting everything spick and span as the means test people are coming today,’ she told me.

I wasn’t sure what exactly that meant, but half an hour later a stern-looking woman in a suit came up to the attic. She opened up the larder door and had a good look inside.

‘As you can see there’s nothing in there,’ my mother told her frostily.

I could tell that Mum was very annoyed to have to ask for help.

‘What’s that lady doing?’ I said.

‘She’s checking to see how much food we’ve got,’ she told me. ‘Or should I say how little.’

I was even put out to work to try to help Mum make ends meet. I remember we were walking to the shop one day when a woman stopped my mother in the street.

‘Oh, what a pretty little thing,’ she said to me. ‘Look at those great big brown eyes.’

I was such a show-off, and even as a toddler I knew how to play to a crowd. I opened my eyes even wider, fluttered my eyelashes and flashed her my best and biggest smile.

‘I know a photographer looking for child models,’ she told Mum. ‘I’m sure he would love your daughter to pose for him.’

The photographer in question turned out to be a very famous man called Marcus Adams. He was a renowned children’s photographer who had taken pictures of King George V’s six children and all of the royal family. Although I couldn’t have been more than three, I remember sitting there in his studio in a little woollen hat and jacket. I was paid three guineas a time, which was quite a lot in those days, and Mum was given copies of the shots, which were very beautiful, pale, sepia photographs printed on soft paper.

Things at home continued to be frosty between Mum and my grandparents. She was allowed downstairs to cook, but then she would always bring our food back up to the attic for us to eat at our little table. We’d never have a meal with them.

My mother was a good cook and we always had lots of fresh vegetables to disguise the fact we couldn’t afford much meat. We’d have our main meal of the day at lunchtime and she’d rustle up pies and stews, apple tarts and cakes. I liked having a boiled egg for tea, which she’d bring up to the attic for me on a silver tray.

Looking back, it was a very peculiar situation. Here were two opposing ideas of life – my mother’s and my grandparents’ – and then me in the middle seeing both sides of it. My grandparents were all right to me and Raymond, and I got on with my grandfather quite well. He used to be a French horn player in the Grenadier Guards, and one afternoon he started stomping up and down the hallway.

‘Come on, Rene,’ he bellowed. ‘Let’s pretend we’re in the Grenadier Guards.’

I giggled as he marched up and down pretending that he was blowing his French horn.

‘Come here and I’ll tell you a story about when I was little,’ he said.

He told me how he grew up in Devon with his father. He’d hated his stepmother, so he ran away from home at the age of fourteen and pretended he was sixteen so he could join the army. He’d never fought but had become a very good French horn player and afterwards had played in the pits in London orchestras.

‘I played at Buckingham Palace for Queen Victoria’s birthday, you know,’ he told me.

‘You met the Queen?’ I gasped. ‘What was she like?’

‘Oh, dreadful woman,’ he grumbled.

‘Why’s that, Papa?’

‘She used to come out on the balcony all in black after her husband had died, and even if it was pouring with rain we’d have to stand there and play for hours. Sometimes she wouldn’t even bother coming out and would just have a quick look out of her bedroom window.’

He also described how he’d played for two very famous dancers, Anna Pavlova and Isadora Duncan.

‘Oh, don’t get me started on that silly Duncan woman,’ he told me. ‘Did you know she strangled herself with her own scarf?’

‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

I listened, wide-eyed, as he recounted the story of how Isadora Duncan was a real lady and used to love wearing these long, floaty scarves.

‘She lived in France, and she was coming over a bridge one day and her long scarf got caught in the axle of the convertible car that she was in and it strangled her. Broke her neck right there on the spot.’

My grandmother was a cold, unemotional woman but she was a fantastic seamstress and dressmaker, and I’d sit there for ages and watch her work. One day she was making a beautiful blue gown that had silk ribbons from the waist down with an underskirt underneath, and at the end of every ribbon there was a silver bell. It was the most beautiful dress that I’d ever seen and I was fascinated.

‘Who’s that dress for, Gaga?’ I asked her.

‘This one is for a Russian princess,’ she said.

It took her hours to sew all the tiny bells on the bottom.

In the front room she had a beautiful old mahogany sewing desk with her Singer sewing machine on the top and dozens of small drawers underneath that were filled with ribbons, beads and different coloured silks. I loved rummaging round in them and touching all of the treasures that were inside.

‘Can I help you tidy up your bits and bobs, Gaga?’ I asked her.

‘As long as you’re careful, Rene,’ she told me. ‘Don’t go pricking your fingers on any needles.’

My biggest wish was for her to make me a princess gown all of my very own. On my fourth birthday she made me a beautiful party dress. It was green cotton with a little collar, puff sleeves and a big bow on the back, and it had frills from the waist down. She even made a matching one for my favourite doll Audrey.

My mum was the eldest of seven children, although two of her brothers had died as toddlers – one had got diphtheria and the other had fallen into the Thames and drowned. It used to cause no end of arguments between my grandparents, as my grandfather could never remember the names of the two that had died and my grandmother used to get really annoyed with him about it.

‘Imagine not remembering your own children,’ she used to say to me. ‘How could he forget his own flesh and blood?’

Mum wasn’t close to her surviving sisters Violet and Winnie or her brothers Arthur and Harry, and they didn’t treat her very nicely. They were all very snobby and wealthy, and they looked on her as a failure when she came back to live with her parents, even though she was a widow. That side of it was all kept from me when I was small, but I began to realise it more as I got older. They didn’t like her choice of husband and the way, in their opinion, she had completely changed her views.

Mum and I stuck together, and we were a close little unit. She had a couple of boyfriends when I was very young, although I don’t remember meeting them. It was only when I was much older that she told me about one man she actually got engaged to.

‘But then he turned around and said that he’d only marry me if I’d agree to put you in a children’s home, so I told him to get knotted,’ she said.

It’s only as I grew up that I started to appreciate how hard it must have been to be a single parent in those days. As I got older, I came to realise that I was different because other children had fathers and I didn’t.

‘Why haven’t I got a daddy like everyone else?’ I asked Mum one day. ‘Where is my daddy?’

She got a dusty album out of a drawer and showed me a photograph. It was a sepia picture of a handsome young man with blond hair and big, expressive brown eyes and dark eyebrows.

‘That was Daddy,’ she said gently. ‘Your lovely dark eyes are just like his.’

There was another black-and-white photograph of Dad in a helmet and goggles standing next to a motorbike.

‘That’s him and his beloved motorbike,’ she told me. ‘He used to strap his cello on the back and go whizzing round London from theatre to theatre.’

Because I didn’t remember anything about Dad it was nice to hear stories about him.

‘Your father was a very unusual man,’ Mum told me. ‘He had strong morals about how children should be treated.’

She described how she had been out one day with him and my brother.

‘We were walking down the road and your father saw another man and his son across the street. The boy was only about five and he must have done something naughty so his father gave him a slap around the legs.

‘Well, when your father saw this he was so angry. He crossed over the road and told the man in no uncertain terms to never, ever hit his child again. I think the man was a bit shocked getting reprimanded by a complete stranger, but I was so proud of your dad.’

It was the norm for children to get a good hiding in those days, but Mum said my father was dead against it and he would always intervene if he saw someone hitting or shouting at a child or treating them badly.

‘Your father was a very gentle man and a great champion of children,’ she said. ‘He was a natural with them. You had bad colic when you were a tiny baby and he’d sit there for hours playing music from the ballet The Dying Swan on his cello trying to soothe you to sleep.’

‘He sounds like a lovely daddy,’ I said sadly.

Hearing how wonderful and kind he was made me feel even sadder that he wasn’t around, and even though I couldn’t really remember him I always felt his loss in my life.

The only father figure I had was my brother Raymond. He’d been very close to my father and I don’t think that he ever got over his death. People didn’t show their feelings in those days, though, and if I ever asked him about my dad, he would clam up.

‘I don’t want to talk about it, Rene,’ he would tell me.

My brother was very academic and clever, and he always bought me books. While other children my age were being read Winnie the Pooh or The Wind in the Willows, he brought me home the complete works of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy.

‘Sit down, Rene,’ he said one day. ‘I’m going to teach you to play chess.’

My father had taught Raymond to play chess and so he decided he was going to teach me. He was a chess whizz but I was four years old and had no interest whatsoever.

‘This is so boring,’ I moaned as we sat and stared at the checked board.

‘Oh, Rene, you’re such a fidget, it’s all about skill,’ he said.

But I preferred something much faster moving, and even though I adored Raymond it didn’t interest me in the slightest.

‘Oh, I give up,’ he said, exasperated. ‘One day, Rene, you’ll find something that you love doing.’

Even though I was only four years old I was about to stumble across something that would become my biggest passion for the rest of my life.

2

Bows and Bombs

Through the darkness I saw them. Dancing around with their floaty wings like beautiful butterflies.

‘Fairies!’ I gasped. ‘I can see fairies!’

I felt as if I were in a dream and I had never seen anything like it in my life. I just sat there on the edge of my seat with my mouth gaping open as I watched these mystical creatures flitting around the stage.

‘Mummy, I want to be one of those,’ I whispered. ‘I want to be a fairy.’

I was four years old and my mother had taken me to see my first ever pantomime – Cinderella at the Grand Theatre, Clapham Junction. I had loved the pumpkin coach, but when the gauze curtain came down all lit up with twinkly lights and these fairies danced across the stage I was absolutely mesmerised. This was the first time I had seen anyone dance, and from then on that was it. I was hooked for the rest of my life.

‘Please can I do that, Mummy?’ I asked afterwards. ‘Can I dance like a fairy?’

‘Well, you could do ballet lessons if you wanted,’ she said.

I didn’t forget about it, and Mum kept her promise and I started going to a weekly lesson at a local ballet school in Clapham. It was in a big house, and one room had been converted into a ballet studio with huge mirrors and a barre down one side. Each lesson cost 2s. 6d. (two shillings and sixpence), and it must have been a struggle for Mum to afford it, but I loved every minute of it and I lived for that day of the week. Leotards hadn’t been invented in those days and tutus were only worn for formal occasions like shows and exams, so I wore a loose black cotton tunic that my grandmother had made me, and I had a piece of pink chiffon wound around my head and tied in a big bow at the back to keep my hair off my face.

I hung on to the ballet mistress’s every word, and I memorised each step and practised until it was perfect.

‘I’d like you to be Greek slave girls today,’ she told us one afternoon. ‘I want you to pretend that you’re holding a vase as you promenade.’

It was very sad, melancholy music, and as I paraded around the room pretending to hold a heavy Grecian urn on my shoulder I felt in my heart I really was that unhappy little slave girl. So much so, I even felt tears in my eyes as I danced.

At the end of the class, when Mum came to collect me, my ballet teacher took her to one side.

‘I think Irene has great potential,’ I heard her say. ‘She really seems to feel the music and her timing is spot on.’

That didn’t mean anything to me. All I knew was that dancing was just another way of being a fairy and I loved it. But just a few weeks after starting my lessons I suddenly got very ill. I was burning up, and all this horrible stuff was oozing out of my right ear. I was in absolute agony.

‘We’d better take you to see the doctor,’ said Mum.

I knew it had to be serious for that to happen. These were the days before the National Health Service, and a visit to the doctor’s surgery cost a lot of money.

The doctor examined me as I whimpered in pain.

‘She has an abscess of the middle ear,’ he told my mother. ‘You need to get her to hospital straight away. If it’s not treated quickly it can be highly dangerous and spread to the brain.’

By then I felt so ill I could barely walk, and Mum had to carry me to St George’s Hospital in Tooting. When we got there she passed me to a doctor.

‘Say goodbye to your mother,’ he told me.

Suddenly I was absolutely terrified. I’d never been away from Mum and I didn’t know where they were taking me or what they were going to do to me.