скачать книгу бесплатно

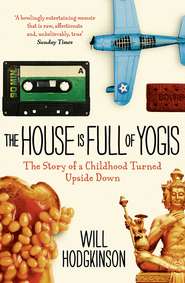

The House is Full of Yogis

Will Hodgkinson

A witty memoir about the trials of adolescence, the tribulations of family life and the embarrassment that ensues from having larger-than-life parentsNeville and Liz Hodgkinson bought into the Thatcherite dream of home ownership, aspiration and advancement. The first children of their working class parents to go to university and have professional careers, they lived in a semi-detached house in Richmond, sent their sons Tom and Will to private school, and went on holiday to Greece once a year. Neville was an award-winning science writer and Liz was a high-earning tabloid hack.Then a disastrous boat holiday, followed by a life-threatening bout of food poisoning from a contaminated turkey, led to the search for a new way of life.Nev joined the Brahma Kumaris, who believe evolution is a myth, time is circular, and a forthcoming Armageddon will make way for a new Golden Age. Out went drunkendinner parties and Victorian décor schemes; in came large women in saris meditating in the living room and lurid paintings of smiling deities on the walls. Liz took the arrival of the Brahma Kumaris as a chance to wage all-out war on convention, from announcing her newfound celibacy on prime time television to writing books that questioned the value of getting married and raising children.By an unfortunate coincidence, this dramatic and highly public transformation of the self coincided with the onset of Will’s adolescence. This is his story.

The House Is Full of Yogis

WILL HODGKINSON

Copyright (#ulink_66ca3e5e-60a0-5a95-838d-62fe2f940cf2)

Borough

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Copyright © Will Hodgkinson 2014

Will Hodgkinson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014 Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007514632

Ebook Edition © June 2014 ISBN: 9780007514618

Version: 2015-02-06

About the Book (#ulink_3661c405-d608-5756-9fde-8f5ddcfd0c1f)

Once upon a time in the 1980s, The Hodgkinsons were just like any other family.

Liz and Neville lived with their sons, Tom and Will, in a semi-detached house in the suburbs of Southwest London. Neville was an award-winning medical correspondent. Liz was a high-earning tabloid journalist. Friends and neighbours turned up to their parties clutching bottles of Mateus Rosé. Then, while recovering from a life-threatening bout of food poisoning, Neville had a Damascene revelation.

Life was never the same again.

Out went drunken dinner parties and Victorian décor schemes. In came hordes of white-clad Yogis meditating in the living room and lectures on the forthcoming apocalypse. Liz took the opportunity to wage all-out war on convention, from denouncing motherhood as a form of slavery to promoting her book Sex Is Not Compulsory on television chat shows, just when Will was discovering girls for the first time.

About the Author (#ulink_5e70c1ea-d40b-5b26-8021-35a18a863d78)

Will Hodgkinson grew up in a larger-than-life family. His father, Neville, was an award-winning science writer until he received a calling from the Brahma Kumaris in 1983. He currently lives with them on a retreat in Oxfordshire. His mother, Liz, continues to write for the Daily Mail. His brother, Tom, created the Idler. As well as working as the rock and pop critic for The Times, Will decided it was high-time to record his family’s colourful story. Will lives in southeast London with his wife and two children.

Praise for The House is Full of Yogis: (#ulink_9c02e6b0-1bb6-5ba6-8ccd-929b54ad3560)

‘A touching account of a family thrust by mid-life crisis into meditation and spiritual awakening … [A] sweet, quirkish gem of a memoir … an affecting, and very funny, evocation of adolescence’

Mick Brown, Telegraph

‘A My Family and Other Middle-Class Animals let loose in the jungle of Thatcher’s suburban Britain. The result is a howlingly entertaining memoir that is raw, affectionate and, unbelievably, true’

Helen Davies, Sunday Times

‘[A] charming, entertaining book’

Melanie Reid, The Times

‘I have been banned from reading in bed as it makes me laugh out loud too much … Punishingly funny, and wonderfully written’

Rachel Johnson, Mail on Sunday

‘Endearing’

Ben East, Observer

‘[Hodgkinson] has a lovely, light style … his set pieces are very funny … He is attentive to the minute social divisions that define the British middle classes … it’s a relief to read a memoir that is so affectionate, so moan-free, so reluctant to apportion blame’

Rachel Cooke, New Statesman

‘An utterly charming, funny and touching memoir’

Sathnam Sanghera, author of Marriage Material

‘A rip-roaringly funny read’

Viv Groskop, Red Magazine

‘Thoughtful, heartfelt and so well drawn … [It] deserves to become as well loved as My Family and Other Animals’

Travis Elborough, author of London Bridge in America

‘I laughed until I levitated’

Jarvis Cocker

Dedication (#ulink_1add9289-48e5-5ff0-a4ba-a03d8b17ae5a)

For Nev, Mum and Tom

Some names have been changed.

(But most have stayed the same.)

Contents

Cover (#u98e7c28a-cf7a-56d3-8660-8048d36c932f)

Title Page (#u72a2f12f-9c8d-583e-9dfb-b6aad29359a1)

Copyright (#u6d0c253d-53a4-5e9b-a7d8-2a100ccb12a8)

About the Book (#ubf66f9ee-7725-5a06-a78f-40e3a0f64520)

About the Author (#u8e6e2577-0182-563b-8794-97cfedc341f0)

Praise for The House is Full of Yogis (#u0b7019d4-db1f-58ba-b873-be3ca4063708)

Dedication (#u3aced86e-9e4c-5c28-99ed-26cee1c2804d)

1. The First Party (#u570e849a-8471-5a6a-91d0-53e546275b03)

2. The Boat Holiday (#u4fb12e82-8d54-51b2-aceb-e3538942cc6e)

3. The Wrong Chicken (#u64a3b713-a461-5343-8da0-4a5912a9fa9a)

4. Nev Returns (#ub0ef63f1-e408-5261-991f-75b4e2dfd6f7)

5. Enter The Brahma Kumaris (#litres_trial_promo)

6. The End Of The World (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The Second Party (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Forest School Camps (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Delinquency (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Frensham Heights (#litres_trial_promo)

11. The Third Party (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Florida (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Sex Is Not Compulsory (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Surrender (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_58136ddf-d4e7-5dee-b0c2-37022e197fea)

The First Party (#ulink_58136ddf-d4e7-5dee-b0c2-37022e197fea)

‘I don’t believe it,’ said Mum.

She was scratching at two cables of ancient wire sticking out of a dusty hole in the brickwork next to the peeling green paint of the front door, after the Volvo had wobbled over the rubble-strewn drive and come to a shaky halt. ‘They’ve even taken the bloody doorbell.’

A year before our father had his Damascene moment, we moved into our first big home.

99, Queens Road was a semi-detached, four-bedroom house on the edge of Richmond, Surrey, which our parents bought for £30,000 from an older couple called the Philpotts. There was no central heating in 99, Queens Road, nor was there a kitchen to speak of; just a Baby Belling cooker, a rattling old fridge and a twin-tub washing machine stranded in the centre of the room like a maiden aunt who had turned up two decades earlier and never left. There was a milk hatch cut into the outside wall that had come free of its hinges.

The Philpotts, who called their 42-year-old son’s room The Nursery and who claimed to speak Ancient Greek on Sundays, had ripped out pretty much everything but the bricks. The carpets had gone. There were no light bulbs. If you opened cupboards you found only empty spaces, suggesting the Philpotts had even filched the shelves.

‘Come on Sturch,’ said my father Nev, using a nickname with a derivation long forgotten. It might have had something to do with Lurch, the monstrously ugly butler from The Addams Family. ‘Let’s go and explore upstairs.’

In our old house, my brother Tom and I shared a bedroom, which was less than ideal because of our very different approaches to being children. One Christmas Eve, I came upstairs after kissing our parents goodnight, fully intending to obey Nev’s gentle command to go to sleep and wait until the morning to see what Santa Claus had brought, knowing I would wake up at three and feel around in the dark for the happy weight of a stocking at the end of my bed. Tom was in there already, constructing an elaborate arrangement of strings and levers. When I asked him what he was doing he told me not to question things I wouldn’t understand.

All was revealed around midnight. When Nev walked in, stockings laden with toys, a hammer hit the light switch, pulling a network of strings running up the wall and activating a camera next to Tom’s bed. Nev’s hair turned into a wild frizz at the shock of it. Satisfied with having disproven the existence of Santa Claus once and for all, Tom dozed off until eight o’clock. He was nine years old.

That was four years ago. ‘Out of the way, Scum,’ said Tom, pushing me aside as he hunched up the stairs of the new house. He looked at the bedroom facing the street, lay down on the single bed the removal men had put in there half an hour earlier, pulled out of his pocket a copy of George Orwell’s 1984, and said without looking up, ‘Oh, do get out of my room.’

There is a photograph in our family album of Tom, an insouciant four-year-old, kicking back in a rusty toy car while I, only two and already so outraged at life’s unfairness that my nappy is exploding out of my shorts, try in vain to push him along. It says it all, really.

Nev and I went to explore the room at the back of the house, which Nev suggested could be my bedroom.

‘Look at this place!’ I said, clomping across squeaking, uneven floorboards. ‘It’s got a window and everything.’ I tried to open it but it just made a juddering sound. ‘And wow, a cupboard with double doors.’ At first they appeared to be jammed, but after giving them a good yank they came open – and flew off their hinges. ‘Oh well. Now the room is even bigger.’

I looked out of the window. The garden was long and thin, with a scrappy strip of lawn, a collapsing shed on the left and a vegetable patch along the right. There was a hole in the ground near the end of the garden, which was surrounded by rotting apples. (The Philpotts had taken the apple tree with them.) There was also a late-middle-aged woman with a helmet of frosted hair, bent over and hurriedly collecting something into a plastic bag.

‘Isn’t that Mrs Philpott?’ I said.

Nev came over and peered through the dirty glass. ‘I believe it is. What on earth is she doing here?’

Mum rushed out of the back door. Mrs Philpott stood up and, arching her eyebrows, said: ‘I’m collecting jasmine.’

Mum took root before her, hands on hips. ‘You do realize that we own this house now.’

Mrs Philpott stared at the younger woman and tilted her head forward, smiled slightly as if dealing with a simpleton, and explained: ‘It costs two pounds at the garden centre.’

Mum smiled back. ‘That may be so. But now you have sold this house to us, so you’re going to have to find somewhere else to snip it.’