скачать книгу бесплатно

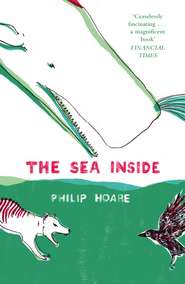

The Sea Inside

Philip Hoare

The sea surrounds us. It gives us life, provides us with the air we breathe and the food we eat. It is where we came from, and it carries our commerce. It represents home and migration, ceaseless change and constant presence. It covers two-thirds of our planet. Yet caught up in our everyday lives, we seem to ignore it, and what it means.In The Sea Inside, Philip Hoare sets out to rediscover the sea, its islands, birds and beasts. He begins on the south coast where he grew up, a place of family memory and an abiding sense of aloneness and almost monastic escape offered by the sea. From there he travels to the other side of the world, from the Isle of Wight to the Azores, from Sri Lanka to Tasmania and New Zealand, in search of encounters with animals and people – the wild and the tamed, the living and the extinct. Navigating between human and natural history, between science and myth, he asks what their stories mean for us now, in the twenty-first century, when the sea has never been so important to our present, as well as to our past and future.Along the way we meet an amazing cast of recluses, outcasts, and travellers; from eccentric artists and scientists to miracle-working saints and tattooed warriors; from gothic ravens to the greatest whales and bizarre creatures that may, or may not, be extinct. The Sea Inside is part bestiary, part memoir, part fantastical travelogue. It takes us on a magical journey of discovery, filled with astounding tales of faith and fear, wilderness and destruction, mortality and beauty. But more than anything, it is the story of the natural world, and the sea inside us all.

The Sea Inside

PHILIP HOARE

FOURTH ESTATE·London

For Cyrus, Max & Lilian

… Even now my heart

Journeys beyond its confines, and my thoughts

Over the sea, across the whale’s domain,

Travel afar the regions of the earth …

‘The Seafarer’, Anglo-Saxon verse

Contents

Title Page (#ud7526258-e598-5a6c-84da-18b1f3febbcc)

Dedication (#uc6d50cab-4a27-5d40-98ed-ec9ebf542553)

Epigraph (#u192e0fff-a762-51c5-b56e-f71c86606230)

1. The suburban sea (#u35df3470-a794-5c1e-a768-f9b7b61fd77a)

2. The white sea (#ubec6f25d-0cec-542f-8ca6-bb889e82a469)

3. The inland sea (#litres_trial_promo)

4. The azure sea (#litres_trial_promo)

5. The sea of serendipity (#litres_trial_promo)

6. The southern sea (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The wandering sea (#litres_trial_promo)

8. The silent sea (#litres_trial_promo)

9. The sea in me (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

Text and Image Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1

The suburban sea

I have lived long enough in the Shire to be

able to afford to go away from it with pleasure.

I suppose this is what homes are for. If one

hadn’t got an anchorage it wouldn’t be

exciting to sail away.

T.H. WHITE, England Have My Bones, 1936

In the years since I have come back to it, the house has grown to become part of me. It is held together by memories, even as it is falling apart. Surrounded by ivy and screened by trees, it has become an enclosed world, left to itself. As I look out from my bedroom window, a blackbird paces out the garage roof, over which a broken willow hangs. Below, tadpoles swim blindly in a slowly leaking pool.

Every day here is the same. I work at the same time, eat my meals at the same time, go out at the same time, go to bed at the same time. I hold fast to my routine, anchoring a life that might otherwise come adrift. But at night the anarchy of my dreams disturbs this self-imposed regime, freefalling till I regain the rituals of the morning.

I’m woken by the cold outside my window, the dark pressing against the glass. I listen to the litany of the forecast, taking me around the coast –

Dogger, Fisher, German Bight, Humber, Thames, Dover, Wight, Portland, Plymouth, Biscay, Trafalgar, FitzRoy, Sole, Lundy, Fastnet, Irish Sea, Shannon, Rockall, Malin, Hebrides, Bailey, Fair Isle, Faeroes

– places I’ll never visit but whose names reassure me with their familiar rhythms, while their remote conditions seem strangely consoling.

Low, losing its identity, mainly fair, moderate or good, falling more slowly, mainly fair in west, occasionally poor in east, good.

I pay attention to the wind direction; not for my boat, but for my bike. A northerly means a chilly but fast ride south, an uphill struggle on my return. A prevailing sou’westerly signals a speedy cycle home, the wind behind my back like a sail. I peer through the curtains for a faint sign that the long night is drawing to a close.

Variable three or less, fog patches at first, becoming mainly good.

Outside, I smell the night-morning air; promising and inviting, or closed-down and denying. I unlock the old brass padlock on the garage door and pull out my bike, feeling for its cable lock like reins.

I follow the same route. I’ve been doing it so long that my bike could steer itself to its destination. Its tyres know every crack in the tarmac, every worn-out white line, every pothole. The urgency of my mission leaves the sleeping houses behind. I ride like my mother walked, at a furious pace, always trying to keep up with myself. As though, if I went fast enough, no one would see me.

It’s December. The colour has yet to seep back into the sky, before the warmth of the night meets the cold of the dawn. My body is geared to the bike. Green lights signal to non-existent cars; I sail through on red. Sodium lamps soak the streets in a Lucozade haze. I ride down the white lines, arms outstretched, reclaiming the road.

Soon I pass out of the suburb’s sprawl, from the land to the sea. Crunching through the shingle, along furrows made on earlier visits, I rumble to a halt at the appointed spot. Leaning my bike against the sea wall, I climb over and – no going back now – lower myself in.

The water is so clear it scares me. Fish leap up as though they’d dropped out of the clouds. Everything is rising to the surface, summoned by the light, slowed to the sea’s heartbeat. The water brims like an overrun bath. I push out through the stillness of the standing tide, my hands creating the only ripples.

I drift out as far as I dare. Borne up by the water, I turn briefly on my back, hips held to the sky, before striking back for the shore. I haul myself out, my body pink and steaming like a wet dog. The scar on my knee is a livid purple; my white T-shirt glows blue in the faint light.

Birds become visible and audible before the sun rises and the world wakes, a netherworld neither dark nor light, out of time. The anonymous Anglo-Saxon poet of ‘The Wanderer’ had a word for it, ūhta, ‘the hour before dawn’, as he travelled by winter, watching ‘the sea birds bathing, stretching out their wings’.

It’s over all too quickly. A frail sun appears over the trees, milky-lemon pale, more like the moon. The morning begins. My body suffers but my spirit soars at having stolen a march on the day; having been rewarded as well as punished. I’ve forgotten my gloves. I stuff one hand, then the other, in my pockets. A skein of geese fly low over the mud. Curlew call out their names – curl-you, curl-you – whistling through their arched bills. Gulls clamour.

Cloud layers over cloud, plum, purple and navy, cocoa, khaki and grey. The cold surrounds me, almost comforting. The light lifts and falls. I smell the iodine of the shore and an intimation of drizzle in the air as the birds’ noise rises in a crescendo, an orchestrated start to the day. The docks rumble into action. A brightly-lit liner sails up the estuary, silent yet so full of people, a distant glimpse of glamour.

The night fades away. I race the ship back to port, flushing a lone and indignant duck from the freshwater pond that has gathered at the mouth of a shingle stream. Somewhere in the woods a woodpecker hammers. The dawn is replaced by ordinary day; the emptiness soon filled by the commonplace. I can see my hands once more. Everything seems to pause in these final moments, as though the performance were put on hold, even as it begins again.

The beach isn’t much of a beach. It’s really all that’s left behind by the slow-moving estuary, more a kind of watery cul-de-sac, fed by two converging rivers. One is filtered through chalk downland to the north-east, flowing through watercress and filled with swerving trout, slowly widening and losing its virginity until it reaches a carved-out bay in the semi-industrial arse-end of the city. Its outer curve, bulwarked by great heaps of rusting cars, is strewn with every imaginable item of litter, deposited by the tidal flow. Its fellow river emerges from the far side of the city, broadening through reed-seeded marshes into the shadow of the docks – a forbidden land where giant cranes stalk like wading birds, and where shiny new cars begin a journey which will end in the same kind of dump in the same kind of city. Yet somehow, somewhere, all this is forgotten in the conjunction of tide and shingle: something quietly miraculous, perpetually renewed.

The sea defines us, connects us, separates us. Most of us experience only its edges, our available wilderness on a crowded island – it’s why we call our coastal towns ‘resorts’, despite their air of decay. And although it seems constant, it is never the same. One day the shore will be swept clean, the next covered by weed; the shingle itself rises and falls. Perpetually renewing and destroying, the sea proposes a beginning and an ending, an alternative to our landlocked state, an existence to which we are tethered when we might rather be set free.

I say it isn’t much of a beach, but that doesn’t do it justice, since it has a beauty all its own – more so for being seldom visited out of season except by dog-walkers and anglers. It is set at the end of a shallow bay that marks the south-eastern limits of the city. To reach it, I ride along a waterfront set with desultory concrete shelters and backed by common land to which are chained half a dozen horses. Behind stands a post-war housing estate, one-quarter of whose population live in poverty.

The path ahead passes through a stand of trees, then gives way to the beach, bordered by a waist-high sea wall with a narrow ledge, just wide enough for a person to walk along. To the landward is a sweep of grass and an avenue of oaks and pines. Gnarled and bowed, they mark an old carriageway that leads, with a grandeur out of all expectation, to a Tudor fort and a Cistercian abbey that once dominated this eastern bank of the estuary. Now the abbey lies in ruins, surrounded by scrubby woods and stagnant stewponds, while the fort, built out of stone robbed from the dissolved abbey, became a grand Victorian pile, recently extended in a replica of itself as a series of expensive apartments.

In this interzone, the modern world has yet to wipe out the past. Although the city is in sight, this place can seem haunted on a winter’s afternoon, with its bare trees bent back by the prevailing sou’westerlies, and its rotting wooden piles, the remains of long-decayed jetties. The yacht club’s boats stand unattended in their pound, the wind rattling nylon lines against aluminium masts in a continual tattoo.

Further down the shore, after an interruption of small shops and terraced houses, is a country park, the site of a huge military hospital. It exerted its own influence for a century or more, but it too has been demolished, absorbed into the turf, leaving only a nuclear shadow and its chapel dome poking through the trees. One day those tower blocks on the shore will be romantic ruins, too, relics of the work of giants.

If the weather is good, I’ll cycle past the park to a far beach, overshadowed by holm oaks rooted in a low bank of gravelly, gorse- and bracken-clad cliffs, where southern England is slowly collapsing into the sea. As I ride, my route parallels the forest on the other side of the estuary. There may be barely three miles between me and its purple heath, but they might as well mark a continental divide. Not only because we are separated by water, but by virtue of what stands on the distant shore and now dominates the entire waterline, a triumvirate of new, industrial installations: oil refinery, chemical plant, and power station.

In the changing light, this cluster of cryptic structures could be anything. Tapering spires for a new place of worship; circular tanks as giant igloos, pale green with rusty streaks; silos like newly-landed space ships; tripod gantries ready to fire salvos of secret missiles. At dawn or dusk, the whole place might be a martial Manhattan, replicating every day, sprouting out of the shore, an alternative new forest of steel. There’s no human scale to this petropolis; it has a curiously temporary feel, although it has been here for half a century. It might be disassembled in a day and imported to some other shore on the other side of the world. Stripped down, utilitarian, it makes no apologies to its surroundings. It has only one function: to make the fuel that confirms its existence. It is brutal, practical, inevitable.

Like the nearby docks, this great complex, which employs more than two thousand workers, is sealed from public access. My own uncle worked there after his wartime service in Kenya, although I couldn’t tell you what he did – any more than I know what he was doing in the middle of Africa in 1943, beyond the photographs of him in khaki shorts and a pith helmet, along with aerogrammes sent out by his family and kept carefully preserved in a Senior Service cigarette tin.

I’ve grown up with this place, which is only just older than me; I have no memory of the virgin shore before the coming of the towers, now imprinted on my view of the shore. Their stacks occasionally burst into life like huge Bunsen burners, as though the whole thing were some gigantic experiment, or a memorial to an unknown warrior. First lit in 1951, these flares commemorate an age of energy and industry, power and destruction. Their function is to burn ‘excess gases’, but as their orange-red tongues lick the sky, they could be drawing directly from the molten depths of the earth, rather than the crude oil from the Middle East which is pumped from tankers that line the mile-long terminal, five abreast like petro-cows waiting to be milked, their bridges branded with slogans, NO SMOKING and PROTECT THE ENVIRONMENT.

To process its daily quota of three hundred thousand barrels of oil, Fawley sucks three hundred thousand tonnes of water from the sea, claiming to return it cleaner than it was before. (In fact, many living organisms are drawn in too: fish are caught in screens and often die, while smaller fry are sent through the factory’s cycle as though through a washing machine, a process which few survive.)

Indeed, the word ‘refinery’ itself is deceptive, since its end products have precisely the opposite effect on the world into which they are released. And while the site is declared to be perfectly safe, its neighbours live in the knowledge that in the event of an emergency, they would be evacuated from their homes, just as the islanders of Tristan da Cunha were evacuated from theirs during the volcanic eruption of 1961, and were brought to a military camp here, in the shadow of the neighbouring power station, close to where their descendants still live. Its cylindrical chimney, an enormous ship’s funnel on a concrete liner fading into pale blue, marks the end of the estuary and the beginning of the sea. Beyond is the tantalising outline of the Isle of Wight and its fields and downs. In the winter, when the trees lack leaves, I can see it from my window, its pairs of red points blinking like landing lights, foreshortening the distance between me and the sea, making it seem suddenly nearer.

Despite its industrial installations and historic layers, this is an unspectacular, unremarkable landscape. You could easily drive by and take away nothing from this place. Many do. No one writes books about this shore. No one who does not live here knows anything much about it, and even those who do would be at pains to report anything noteworthy about the place they see every day.

I just happen to live here. I didn’t choose to; it chose me. I might have found a more picturesque place, wild and romantic or urban and exciting; the kind of places people pass through here to reach. A port city relies on its relationship to elsewhere. Perhaps that’s why I like it so well, since it does not impose any identity on me. I came back here from habit as much as choice, like the birds that migrate to and from its non-descript shores.

You assume you know your home. It’s only when you return that you realise how strange it is. I first saw this beach half a century ago, but all those years have made it seem less rather than more familiar. I’ve taken it for granted. But now, as I look out over its expanse, it occurs to me that what I thought I knew, I didn’t really know at all.

The first recorded settlement here was Roman – the port of Clausentum – followed by Anglo-Saxon Hamwic; Southampton translates out of Old English as ‘south home town’. Sholing, where I live, barely existed until modern times: its name is a contraction of ‘Shore Land’; its neighbour, Netley, means ‘wet wood’. Until the nineteenth century, this was common land, coursed by a Roman road and scattered with tumuli and cottages; an oddly isolated area, separated from the rest of Hampshire on three sides by rivers and the sea. Troops trained here; shanty towns of huts were set up for navigators working on the railway line and the sprawling military hospital. Their presence may have been why this place became known as Spike Island, a slur on its itinerant population of travellers and horse-traders, and a wry reference to a notorious penal colony of the same name in Ireland’s Cork Harbour, Inis Pich. There was a wildness to this heathland. One corner was named Botany Bay, after the destination of the transportees who were held there – as their Irish counterparts were in Cork Harbour – before being shipped out to the ends of the earth.

Even now, this eastern side of Southampton Water can feel insular, outcast. A place through which to pass, rather than to stop at for its own sake. There’s a sense that anything could happen here and already has, caught up in the flow of changing tides and people and animals and beginnings and endings, the obscure currents of history.

Recently, I flew home after spending some days on the banks of a Scottish sea-loch. The north had been dramatic, monumental, with rivers of mist running down granite valleys, falling like dry ice into the still, deep water from which the mountains rose on the other side, blue-purple and faintly oppressive. The skies were overcast by the damp Gulf Stream and second-hand winds from the Caribbean. Flying back south, I felt an immense lifting of the atmosphere as the sun broke through the clouds and the plane banked over Southampton.

In those few minutes I saw the past and present unroll beneath me, as in a camera obscura. The horizon had vanished, to be replaced by a careering view, as chaotic as it was ordered. The plexiglass porthole filtered the light like a prism, and gave the scene a watery air. I might have been looking out from the side of a ship or even from a submarine.

Down there, somewhere, was my house, sheltered by trees and shrubs. To the south lay the sea, a broad strip of blue-green bordered by yellow shingle. As the plane flew over the beach I knew so well, but could hardly recognise from this angle, it turned back from the forest and into the heart of the docks, passing monumental cranes and ocean liners lined up like bath toys, swimming pools shimmering in the sun. Then it flew over the bridge that connects one side of the city to the other, over the school I first attended more than four decades ago.

The afternoon sun lent it all a glowing sheen, highlighting every reflective surface. Even the scrapyard and its defunct cars reduced to metal screes acquired an allure, shining like piles of iron filings. Seeing all this laid before me, even after only a few days away, made me intensely happy and profoundly sad, its streets and shores so familiar that they seemed extensions of my own body. Finally, descending to the airport, we touched down on southern soil once more.

This suburban sea is a living thing, ever shifting as it is contained. Everything seems open to the light, some subtle combination that has never been seen before and will never be seen again: the sun forced from under a bank of cloud, a pure white egret like a flapping appar-ition, a pair of mute swans gliding close to shore. Even on the dreariest days, the most forlorn afternoons, it’s never not beautiful here. The slow surging waves seem to be suppressed by the mist, yet every sense is heightened. I can smell the forest across the water. Sound behaves differently; with no buildings to bounce from, it spreads over the surface and soaks back into the sea.

Black-headed gulls, barely more than pale smears, splash their heads and wings. Unresolved shapes drift by. Everything coalesces, caught in a dreamy, half-hallucinatory loop. There are shadows under the water as it withdraws over weed and rusty outfall pipes. A distant yacht becomes a silent white smudge. A fall of black crows scatter in the murk. The saturated greens and browns of grass and leaves turn the colour balance awry, in the way that reds and greens take on an eerie vividness before a storm, when the pressure appears to affect the light itself.

My time is determined by the ebb and flow. At low tide, the beach is an indecent expanse laid bare by retreat, more like farmland than anything of the sea: an inundated field, almost peaty with sediment, as much charcoal as it is sludge.

Bait-diggers leave little piles by their sides like slumped sandcastles. With their buckets and spades, they might as well be burying as disinterring, these sextons of the shore. Standing over them is an outfall marker in the shape of an X, which has turned to become a cross. In the uncertain light, the mud takes on new colours, from black to taupe and even a kind of rubbed silver.

As I say, it is never not beautiful here.

Behind me, bare oaks and beeches lie as cracks against the sky, evoking a peculiarly English landscape. In the late eighteenth century, Turner drew the abbey’s ruins in his sketchbook, tracing out the trees that had grown up around the crumbling gothic arches. In 1816 John Constable stayed at Netley on his honeymoon, and painted its scudding clouds and billowing greenery. Theirs were records of a Romantic setting, an alternative reality of sensation and emotion. Hanging over the shore, the gnarled, enamelled branches are made darker by the reflected light of the sea and the stretch of bright shingle. My shortening eyesight renders it all abstract, blurring the scene like Turner’s evocations of nothingness, with their vague shapes that might be waves or whales or slaves tossed overboard, rising and falling in foam with ‘a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it’, as Ishmael says in Moby-Dick, ‘until you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvellous painting meant’.

That fixity of sea and sky is a supreme deception. Over it lies what Herman Melville called the ocean’s skin – a permeable membrane, one-sixteenth of a millimetre thick, fertile with particles and micro-organisms and contaminants; a fantastically fragile yet vast division. The horizon is only an invention of our eyes and brains as we seek to make sense of that immensity and locate our selves within it. The sea solicits such illusions. It takes its colour from the clouds, becomes a sky fallen to the earth; it only suggests what it might or might not contain. Little wonder that people once thought the sun sank into the sea, just as the moon rose out of it.

Not many artists come here now to see the sun set or the moon rise. Netley’s beach is hardly thronged with easels, and Turner and Constable left long before the refinery turned the shore spiky with petro-chemical romance. Perhaps the strangest thing about this massed industry is its absence of sound, at least at this distance, both innocent and ominous at the same time, although occasionally the plant emits a dull indefinable roar, like a giant stirring in its sleep.

This is a place both dead and alive. Being here, in or by the water, at either end of such a cold, closed-down day makes me physically part of it. A crested grebe pops up, charting the shallows for its prey. It arches its neck to dive again, as I swim towards it. A jumpy, almost nervous plunge, a little leap forward, then it’s gone.

As with so many things about birds, you have to take a lot on trust; to discern what is real, and what they want you to believe. The pattern of a duck’s feathers, for instance, breaks up the surface, blurring its body between water and sky, an effect that prompted the American artist Abbott Thayer to suggest eye-dazzling camouflage for First World War soldiers and ships, mimicking natural cover in an industrial war. A grebe’s markings, intensely detailed against the grey of the sea, may seem darkly obvious to us, but from below, its white throat and breast renders it invisible, able to deal death with its stiletto bill. Thayer called this disguise ‘counter-shading’; it lends animals from birds to whales a flat deception in the overhead sun, making them seem insubstantial rather than solid things.

As they emerge from their dives, I realise that there are half a dozen birds patrolling, moving into their winter haunts. From their own level, in the water, I feel accepted, or at least tolerated – any bird will have seen you long before you see it. I’m too far away to see the grebe’s blood-red eyes, although there’s a suggestion, even at this distance, of the outrageous ruffs which once supplied Edwardian society with stolen plumage. But then, grebe parents will pluck out their own feathers to feed their chicks, lining their young stomachs against fish bones.

The tide ebbs, and the birds assemble, as if someone had laid the table and called them in to dinner. Gulls and geese are already working the shoreline, as are the oyster-catchers, in their white winter ‘scarves’. They’re one of my favourite birds: familiar, stalwart, forever looking out to sea.

Untrue to its name, imported from its American cousin, the Eurasian oystercatcher eats mostly mussels and cockles teased from the shore, using its greatest asset: a bone-strengthened bill, part hammer, part chisel, able to prise open the biggest bivalves. Delicately coloured carrot-red to toucan-yellow – it might be made of porcelain – it is a surprisingly sensitive probe. At its tip are specialised Herbst corpuscles that allow the bird to sense its prey by touch as well as sight; an oystercatcher can forage as well by night as by day. Perpetually prospecting the beach, it stabs and pecks or ‘sows’ and ‘ploughs’, altering its methods to suit its prey. It can even change the shape of its bill – the fastest-growing of any bird – morphing from blunt mussel-blade to fine worm-teaser in a matter of days.

Living and dying by its wits, the oystercatcher has evolved to take advantage of its environment. It has been present on Southampton Water for centuries, if not millennia: graffiti’d into the sixteenth-century plaster wall of the port’s oldest house is an oystercatcher, a scratchy Tudor cartoon of an animal familiar from the nearby shore. In 1758, Linnaeus classified it as Haematopus ostralegus – blood-footed oyster-picker – but in Britain, where it was prized as a dish, it was called sea pie and was reduced to near-extinction in some southern sites. In modern times the birds were seen as threats to cockle beds: from 1956 to 1969, some sixteen thousand were shot in Morecambe Bay alone.

My oystercatchers, if you’ll forgive the proprietary tone, may feed and roost here, but they nest as far away as Belgium and Norway. They’d do well to steer clear of France, where hunters still shoot two thousand of them every year for recreation, sometimes ten times that many. These monogamous animals have complex social structures and can reach forty years or more, the longest-living wading bird. And they always return here, where they feel most at home. Their peeping calls drift over the water as they fly in low formation, wings emblazoned with white streaks. They settle to forage on the tideline, occasionally breaking into indignant arguments.

I raise my binoculars. I spy on them, they spy on me, one eye always on the stranger. As I watch, they’re joined by ringed plovers. The skittish newcomers bank in synchronised circles, suddenly swerving as if they’d hit some unseen current, then performing a deft communal turn to land. As they do so a gull takes off clumsily, lurching into their flight path and causing them to scatter. Rapid wings rev into reverse. All of a sudden, they’re on the ground, camouflaged bodies merging into the mud.

As timid as they are, the plovers are unfazed by the ever-present carrion crows that have established themselves here, a black-flapping backdrop in the car park. Overnight they’ll empty the bins like delinquent dustmen, leaving the tarmac strewn with the guilty evidence of their scavenging. Surveying the drifting fish-and-chip wrappers, they avert their eyes as if to say, ‘It wasn’t us.’ Although my books tell me that they’re solitary animals, they gather here in a great fluid flock of two hundred or more. Perhaps they’re evolving into aquatic birds, just as the gulls have moved inland to rubbish tips and shopping precincts.

There are other worlds of communication going on here, unknown orchestrations of action. Every so often the crows will rise up in waves, bird-shaped holes in the sky. They’re a lustrous lack of colour, denuded of detail; a fluttering negation, as dark as the night. Ted Hughes, who made a new myth of the crow, saw the bird as suffering everything even as it suffers nothing. Encouraged by its ugly name, we indict its assemblies as ‘murders’; yet crows mark the passing of one of their number in funereal demonstrations, cawing their grief in the way elephants and whales mourn their dead.

These ignored birds – whose ubiquity only makes them less visible – display the fascinating behaviour of their family. Broad-shouldered males swagger from one leg to another. Using their thick, oiled-ebony beaks, they peck over stones so much more dexterously than a wader or a gull. There’s a determined, discretionary air to their epicene foraging, although actually they’ll eat almost anything. They seem surprised if you stop and look at them, as though no one had bothered to do so before. They stare back briefly, abashed, then turn away, unable to believe that anyone other than their own might find them interesting. Or perhaps there is disdainful pride in that sideways glance, assuming the reverse: that they are the most intelligent of all birds.

As indeed they are. Raptors may be more majestic, songbirds sing more sweetly, waders are more elegantly poised, but corvids such as crows and ravens exceed them all in matters of the mind.

You can see it in their body language. They’re full of character, with their grizzled, quizzical stances; individuals, possessed of particular attributes. Their eyes glitter and their heads swivel with curiosity, ever alert to what is going on around them. Bold and twitchy, timid and territorial, their restlessness is a sure sign that something is going on in their heads. Singly or en masse, they react to every sound and movement. They’re always aware of what the others are doing: fighting, preening, competing, conspiring, minding each other’s business to see if it can be outdone. If a fight breaks out between two of them, the others will swoop in from the trees around to see what’s going on, like children in the playground chanting Fight, fight, fight. They’re irredeemably nosy, socially-adjusted birds.

Crows appear crafty to our eyes, since we seem to find intelligence in any other species than our own suspicious (I write all this down in my policeman’s notebook, as if I were about to arrest one of the avian young offenders). They’re an alternative community over our heads; gypsy birds, a mysterious race with their own hinterland. They live on the periphery in the way that all animals do, existing on the same plane as we do but inhabiting another time and space. They even have their own voices, resembling the patterns of human speech: captive corvids can be taught to speak as well as, if not better than parrots; it is one reason why they were said to be carriers of dead men’s souls. Acting in loose unison, at some unspoken signal they will fly out of the woods and onto the shore, as if they were the spirits of the monks evicted from their dissolved abbey. No one really knows what they do or how they think. Perhaps theirs is just a convenient congregation, only motivated by food and sex. But then, you might say the same about us. As a species, we are unable to resist the temptation to impose our own failings on animals; it’s almost an act of transference, and I’m as guilty as anyone else.