Полная версия:

Unbroken

LAURA HILLENBRAND

Unbroken

An Extraordinary True Story of

Courage and Survival

Copyright

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thestate.co.uk

Originally published in the United States by Random House in 2010

Copyright © Laura Hillenbrand 2010

The right of Laura Hillenbrand to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

HB ISBN 9780007378012

TPB ISBN 9780007386642

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007378029

Version: 2018-07-06

For the wounded and the lost

What stays with you latest and deepest? of curious panics, Of hard-fought engagements or sieges tremendous what deepest remains?

—Walt Whitman, “The Wound-Dresser”

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

PREFACE

PART I

One The One-Boy Insurgency

Two Run Like Mad

Three The Torrance Tornado

Four Plundering Germany

Five Into War

PART II

Six The Flying Coffin

Seven “This Is It, Boys”

Eight “Only the Laundry Knew How Scared I Was”

Nine Five Hundred and Ninety-four Holes

Ten The Stinking Six

Eleven “Nobody’s Going to Live Through This”

PART III

Twelve Downed

Thirteen Missing at Sea

Fourteen Thirst

Fifteen Sharks and Bullets

Sixteen Singing in the Clouds

Seventeen Typhoon

PART IV

Eighteen A Dead Body Breathing

Nineteen Two Hundred Silent Men

Twenty Farting for Hirohito

Twenty-one Belief

Twenty-two Plots Afoot

Twenty-three Monster

Twenty-four Hunted

Twenty-five B-29

Twenty-six Madness

Twenty-seven Falling Down

Twenty-eight Enslaved

Twenty-nine Two Hundred and Twenty Punches

Thirty The Boiling City

Thirty-one The Naked Stampede

Thirty-two Cascades of Pink Peaches

Thirty-three Mother’s Day

PART V

Thirty-four The Shimmering Girl

Thirty-five Coming Undone

Thirty-six The Body on the Mountain

Thirty-seven Twisted Ropes

Thirty-eight A Beckoning Whistle

Thirty-nine Daybreak

EPILOGUE

NOTES

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Also by Laura Hillenbrand

About the Publisher

PREFACE

ALL HE COULD SEE, IN EVERY DIRECTION, WAS WATER.

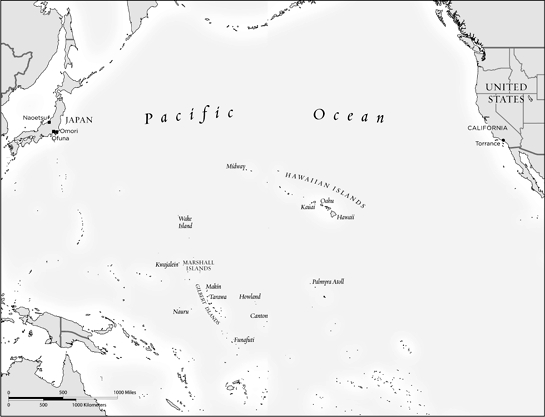

It was June 23, 1943. Somewhere on the endless expanse of the Pacific Ocean, Army Air Forces bombardier and Olympic runner Louie Zamperini lay across a small raft, drifting westward. Slumped alongside him was a sergeant, one of his plane’s gunners. On a separate raft, tethered to the first, lay another crewman, a gash zigzagging across his forehead. Their bodies, burned by the sun and stained yellow from the raft dye, had winnowed down to skeletons. Sharks glided in lazy loops around them, dragging their backs along the rafts, waiting.

The men had been adrift for twenty-seven days. Borne by an equatorial current, they had floated at least one thousand miles, deep into Japanese-controlled waters. The rafts were beginning to deteriorate into jelly, and gave off a sour, burning odor. The men’s bodies were pocked with salt sores, and their lips were so swollen that they pressed into their nostrils and chins. They spent their days with their eyes fixed on the sky, singing “White Christmas,” muttering about food. No one was even looking for them anymore. They were alone on sixty-four million square miles of ocean.

A month earlier, twenty-six-year-old Zamperini had been one of the greatest runners in the world, expected by many to be the first to break the four-minute mile, one of the most celebrated barriers in sport. Now his Olympian’s body had wasted to less than one hundred pounds and his famous legs could no longer lift him. Almost everyone outside of his family had given him up for dead.

On that morning of the twenty-seventh day, the men heard a distant, deep strumming. Every airman knew that sound: pistons. Their eyes caught a glint in the sky—a plane, high overhead. Zamperini fired two flares and shook powdered dye into the water, enveloping the rafts in a circle of vivid orange. The plane kept going, slowly disappearing. The men sagged. Then the sound returned, and the plane came back into view. The crew had seen them.

With arms shrunken to little more than bone and yellowed skin, the castaways waved and shouted, their voices thin from thirst. The plane dropped low and swept alongside the rafts. Zamperini saw the profiles of the crewmen, dark against bright blueness.

There was a terrific roaring sound. The water, and the rafts themselves, seemed to boil. It was machine gun fire. This was not an American rescue plane. It was a Japanese bomber.

The men pitched themselves into the water and hung together under the rafts, cringing as bullets punched through the rubber and sliced effervescent lines in the water around their faces. The firing blazed on, then sputtered out as the bomber overshot them. The men dragged themselves back onto the one raft that was still mostly inflated. The bomber banked sideways, circling toward them again. As it leveled off, Zamperini could see the muzzles of the machine guns, aimed directly at them.

Zamperini looked toward his crewmates. They were too weak to go back in the water. As they lay down on the floor of the raft, hands over their heads, Zamperini splashed overboard alone.

Somewhere beneath him, the sharks were done waiting. They bent their bodies in the water and swam toward the man under the raft.

PART I

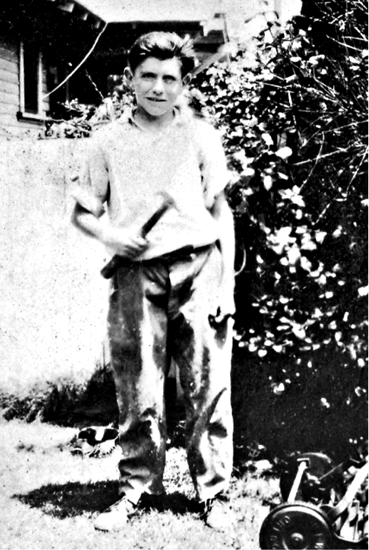

Courtesy of Louis Zamperini. Photo of original image by John Brodkin.

One The One-Boy Insurgency

IN THE PREDAWN DARKNESS OF AUGUST 26, 1929, IN THE back bedroom of a small house in Torrance, California, a twelve-year-old boy sat up in bed, listening. There was a sound coming from outside, growing ever louder. It was a huge, heavy rush, suggesting immensity, a great parting of air. It was coming from directly above the house. The boy swung his legs off his bed, raced down the stairs, slapped open the back door, and loped onto the grass. The yard was otherworldly, smothered in unnatural darkness, shivering with sound. The boy stood on the lawn beside his older brother, head thrown back, spellbound.

The sky had disappeared. An object that he could see only in silhouette, reaching across a massive arc of space, was suspended low in the air over the house. It was longer than two and a half football fields and as tall as a city. It was putting out the stars.

What he saw was the German dirigible Graf Zeppelin. At nearly 800 feet long and 110 feet high, it was the largest flying machine ever crafted. More luxurious than the finest airplane, gliding effortlessly over huge distances, built on a scale that left spectators gasping, it was, in the summer of ‘29, the wonder of the world.

The airship was three days from completing a sensational feat of aeronautics, circumnavigation of the globe. The journey had begun on August 7, when the Zeppelin had slipped its tethers in Lakehurst, New Jersey, lifted up with a long, slow sigh, and headed for Manhattan. On Fifth Avenue that summer, demolition was soon to begin on the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, clearing the way for a skyscraper of unprecedented proportions, the Empire State Building. At Yankee Stadium, in the Bronx, players were debuting numbered uniforms: Lou Gehrig wore No. 4; Babe Ruth, about to hit his five hundredth home run, wore No. 3. On Wall Street, stock prices were racing toward an all-time high.

After a slow glide around the Statue of Liberty, the Zeppelin banked north, then turned out over the Atlantic. In time, land came below again: France, Switzerland, Germany. The ship passed over Nuremberg, where fringe politician Adolf Hitler, whose Nazi Party had been trounced in the 1928 elections, had just delivered a speech touting selective infanticide. Then it flew east of Frankfurt, where a Jewish woman named Edith Frank was caring for her newborn, a girl named Anne. Sailing northeast, the Zeppelin crossed over Russia. Siberian villagers, so isolated that they’d never even seen a train, fell to their knees at the sight of it.

On August 19, as some four million Japanese waved handkerchiefs and shouted “Banzai!” the Zeppelin circled Tokyo and sank onto a landing field. Four days later, as the German and Japanese anthems played, the ship rose into the grasp of a typhoon that whisked it over the Pacific at breathtaking speed, toward America. Passengers gazing from the windows saw only the ship’s shadow, following it along the clouds “like a huge shark swimming alongside.” When the clouds parted, the passengers glimpsed giant creatures, turning in the sea, that looked like monsters.

On August 25, the Zeppelin reached San Francisco. After being cheered down the California coast, it slid through sunset, into darkness and silence, and across midnight. As slow as the drifting wind, it passed over Torrance, where its only audience was a scattering of drowsy souls, among them the boy in his pajamas behind the house on Gramercy Avenue.

Standing under the airship, his feet bare in the grass, he was transfixed. It was, he would say, “fearfully beautiful.” He could feel the rumble of the craft’s engines tilling the air but couldn’t make out the silver skin, the sweeping ribs, the finned tail. He could see only the blackness of the space it inhabited. It was not a great presence but a great absence, a geometric ocean of darkness that seemed to swallow heaven itself.

The boy’s name was Louis Silvie Zamperini. The son of Italian immigrants, he had come into the world in Olean, New York, on January 26, 1917, eleven and a half pounds of baby under black hair as coarse as barbed wire. His father, Anthony, had been living on his own since age fourteen, first as a coal miner and boxer, then as a construction worker. His mother, Louise, was a petite, playful beauty, sixteen at marriage and eighteen when Louie was born. In their apartment, where only Italian was spoken, Louise and Anthony called their boy Toots.

From the moment he could walk, Louie couldn’t bear to be corralled. His siblings would recall him careening about, hurdling flora, fauna, and furniture. The instant Louise thumped him into a chair and told him to be still, he vanished. If she didn’t have her squirming boy clutched in her hands, she usually had no idea where he was.

In 1919, when two-year-old Louie was down with pneumonia, he climbed out his bedroom window, descended one story, and went on a naked tear down the street with a policeman chasing him and a crowd watching in amazement. Soon after, on a pediatrician’s advice, Louise and Anthony decided to move their children to the warmer climes of California. Sometime after their train pulled out of Grand Central Station, Louie bolted, ran the length of the train, and leapt from the caboose. Standing with his frantic mother as the train rolled backward in search of the lost boy, Louie’s older brother, Pete, spotted Louie strolling up the track in perfect serenity. Swept up in his mother’s arms, Louie smiled. “I knew you’d come back,” he said in Italian.

In California, Anthony landed a job as a railway electrician and bought a half-acre field on the edge of Torrance, population 1,800. He and Louise hammered up a one-room shack with no running water, an outhouse behind, and a roof that leaked so badly that they had to keep buckets on the beds. With only hook latches for locks, Louise took to sitting by the front door on an apple box with a rolling pin in her hand, ready to brain any prowlers who might threaten her children.

There, and at the Gramercy Avenue house where they settled a year later, Louise kept prowlers out, but couldn’t keep Louie in hand. Contesting a footrace across a busy highway, he just missed getting broadsided by a jalopy. At five, he started smoking, picking up discarded cigarette butts while walking to kindergarten. He began drinking one night when he was eight; he hid under the dinner table, snatched glasses of wine, drank them all dry, staggered outside, and fell into a rosebush.

On one day, Louise discovered that Louie had impaled his leg on a bamboo beam; on another, she had to ask a neighbor to sew Louie’s severed toe back on. When Louie came home drenched in oil after scaling an oil rig, diving into a sump well, and nearly drowning, it took a gallon of turpentine and a lot of scrubbing before Anthony recognized his son again.

Thrilled by the crashing of boundaries, Louie was untamable. As he grew into his uncommonly clever mind, mere feats of daring were no longer satisfying. In Torrance, a one-boy insurgency was born.

If it was edible, Louie stole it. He skulked down alleys, a roll of lock-picking wire in his pocket. Housewives who stepped from their kitchens would return to find that their suppers had disappeared. Residents looking out their back windows might catch a glimpse of a long-legged boy dashing down the alley, a whole cake balanced on his hands. When a local family left Louie off their dinner-party guest list, he broke into their house, bribed their Great Dane with a bone, and cleaned out their icebox. At another party, he absconded with an entire keg of beer. When he discovered that the cooling tables at Meinzer’s Bakery stood within an arm’s length of the back door, he began picking the lock, snatching pies, eating until he was full, and reserving the rest as ammunition for ambushes. When rival thieves took up the racket, he suspended the stealing until the culprits were caught and the bakery owners dropped their guard. Then he ordered his friends to rob Meinzer’s again.

It is a testament to the content of Louie’s childhood that his stories about it usually ended with “… and then I ran like mad.” He was often chased by people he had robbed, and at least two people threatened to shoot him. To minimize the evidence found on him when the police habitually came his way, he set up loot-stashing sites around town, including a three-seater cave that he dug in a nearby forest. Under the Torrance High bleachers, Pete once found a stolen wine jug that Louie had hidden there. It was teeming with inebriated ants.

In the lobby of the Torrance theater, Louie stopped up the pay telephone’s coin slots with toilet paper. He returned regularly to feed wire behind the coins stacked up inside, hook the paper, and fill his palms with change. A metal dealer never guessed that the grinning Italian kid who often came by to sell him armfuls of copper scrap had stolen the same scrap from his lot the night before. Discovering, while scuffling with an enemy at a circus, that adults would give quarters to fighting kids to pacify them, Louie declared a truce with the enemy and they cruised around staging brawls before strangers.

To get even with a railcar conductor who wouldn’t stop for him, Louie greased the rails. When a teacher made him stand in a corner for spitballing, he deflated her car tires with toothpicks. After setting a legitimate Boy Scout state record in friction-fire ignition, he broke his record by soaking his tinder in gasoline and mixing it with match heads, causing a small explosion. He stole a neighbor’s coffee percolator tube, set up a sniper’s nest in a tree, crammed pepper-tree berries into his mouth, spat them through the tube, and sent the neighborhood girls running.

His magnum opus became legend. Late one night, Louie climbed the steeple of a Baptist church, rigged the bell with piano wire, strung the wire into a nearby tree, and roused the police, the fire department, and all of Torrance with apparently spontaneous pealing. The more credulous townsfolk called it a sign from God.

Only one thing scared him. When Louie was in late boyhood, a pilot landed a plane near Torrance and took Louie up for a flight. One might have expected such an intrepid child to be ecstatic, but the speed and altitude frightened him. From that day on, he wanted nothing to do with airplanes.

In a childhood of artful dodging, Louie made more than just mischief. He shaped who he would be in manhood. Confident that he was clever, resourceful, and bold enough to escape any predicament, he was almost incapable of discouragement. When history carried him into war, this resilient optimism would define him.

Louie was twenty months younger than his brother, who was everything he was not. Pete Zamperini was handsome, popular, impeccably groomed, polite to elders and avuncular to juniors, silky smooth with girls, and blessed with such sound judgment that even when he was a child, his parents consulted him on difficult decisions. He ushered his mother into her seat at dinner, turned in at seven, and tucked his alarm clock under his pillow so as not to wake Louie, with whom he shared a bed. He rose at two-thirty to run a three-hour paper route, and deposited all his earnings in the bank, which would swallow every penny when the Depression hit. He had a lovely singing voice and a gallant habit of carrying pins in his pant cuffs, in case his dance partner’s dress strap failed. He once saved a girl from drowning. Pete radiated a gentle but impressive authority that led everyone he met, even adults, to be swayed by his opinion. Even Louie, who made a religion out of heeding no one, did as Pete said.

Louie idolized Pete, who watched over him and their younger sisters, Sylvia and Virginia, with paternal protectiveness. But Louie was eclipsed, and he never heard the end of it. Sylvia would recall her mother tearfully telling Louie how she wished he could be more like Pete. What made it more galling was that Pete’s reputation was part myth. Though Pete earned grades little better than Louie’s failing ones, his principal assumed that he was a straight-A student. On the night of Torrance’s church bell miracle, a well-directed flashlight would have revealed Pete’s legs dangling from the tree alongside Louie’s. And Louie wasn’t always the only Zamperini boy who could be seen sprinting down the alley with food that had lately belonged to the neighbors. But it never occurred to anyone to suspect Pete of anything. “Pete never got caught,” said Sylvia. “Louie always got caught.”

Nothing about Louie fit with other kids. He was a puny boy, and in his first years in Torrance, his lungs were still compromised enough from the pneumonia that in picnic footraces, every girl in town could dust him. His features, which would later settle into pleasant collaboration, were growing at different rates, giving him a curious face that seemed designed by committee. His ears leaned sidelong off his head like holstered pistols, and above them waved a calamity of black hair that mortified him. He attacked it with his aunt Margie’s hot iron, hobbled it in a silk stocking every night, and slathered it with so much olive oil that flies trailed him to school. It did no good.

And then there was his ethnicity. In Torrance in the early 1920s, Italians were held in such disdain that when the Zamperinis arrived, the neighbors petitioned the city council to keep them out. Louie, who knew only a smattering of English until he was in grade school, couldn’t hide his pedigree. He survived kindergarten by keeping mum, but in first grade, when he blurted out “Brutte bastarde!” at another kid, his teachers caught on. They compounded his misery by holding him back a grade.

He was a marked boy. Bullies, drawn by his oddity and hoping to goad him into uttering Italian curses, pelted him with rocks, taunted him, punched him, and kicked him. He tried buying their mercy with his lunch, but they pummeled him anyway, leaving him bloody. He could have ended the beatings by running away or succumbing to tears, but he refused to do either. “You could beat him to death,” said Sylvia, “and he wouldn’t say ‘ouch’ or cry.” He just put his hands in front of his face and took it.

As Louie neared his teens, he took a hard turn. Aloof and bristling, he lurked around the edges of Torrance, his only friendships forged loosely with rough boys who followed his lead. He became so germophobic that he wouldn’t tolerate anyone coming near his food. Though he could be a sweet boy, he was often short-tempered and obstreperous. He feigned toughness, but was secretly tormented. Kids passing into parties would see him lingering outside, unable to work up the courage to walk in.

Frustrated at his inability to defend himself, he made a study of it. His father taught him how to work a punching bag and made him a barbell from two lead-filled coffee cans welded to a pipe. The next time a bully came at Louie, he ducked left and swung his right fist straight into the boy’s mouth. The bully shrieked, his tooth broken, and fled. The feeling of lightness that Louie experienced on his walk home was one he would never forget.

Over time, Louie’s temper grew wilder, his fuse shorter, his skills sharper. He socked a girl. He pushed a teacher. He pelted a policeman with rotten tomatoes. Kids who crossed him wound up with fat lips, and bullies learned to give him a wide berth. He once came upon Pete in their front yard, in a standoff with another boy. Both boys had their fists in front of their chins, each waiting for the other to swing. “Louie can’t stand it,” remembered Pete. “He’s standing there, ‘Hit him, Pete! Hit him, Pete!’ I’m waiting there, and all of a sudden Louie turns around and smacks this guy right in the gut. And then he runs!”