Полная версия:

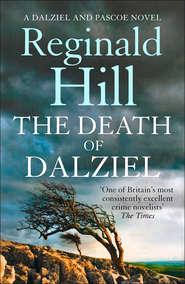

The Death of Dalziel: A Dalziel and Pascoe Novel

REGINALD HILL

THE DEATH OF DALZIEL

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain

by HarperCollinsPublishers 2007

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2007

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007313228

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007353590

Version: 2015-06-25

For the peacemakerswhichever god’s children they are

What, old acquaintance? Could not all this flesh Keep in a little life? Poor Jack, farewell…Death hath not struck so fat a deer today.

Shakespeare Henry IV Part 1, Act V scene iv

A Knight of the Temple who kills an evil man should not be condemned for killing the man but praised for killing the evil.

St Bernard of Clairvaux,

Liber ad milites Templi

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

1 mill street

2 two mutton pasties and an almond slice

3 intimations

4 dust and ashes

5 the two Geoffreys

6 blue smartie

7 dancing with death

8 blame

Part Two

1 a tidy desk

2 show business

3 walking the dog

4 dead men don’t fart!

5 age of wonders

Part Three

1 Lubyanka

2 a pale horse

3 kaffee-klatsch

4 burglary

5 all the way home

6 an urban fox

7 Sauron’s eye

8 now it’s safe

Part Four

1 the shock of recognition

2 Rule Five

3 Hectoring

4 Troy

5 fiddle-de-dee

6 Kilda

7 in the mood

8 without fear or favour

9 the decisive moment

10 queen of the fête

11 forgotten dreams

12 the man of my dreams

13 no change

14 the tangle o’ the Isles

15 a shot in the dark

16 the word of an Englishman

Part Five

1 a free lunch

2 promotion

3 melodious twang

4 red mite and greenfly

5 no-name

6 wake-up call

7 safe house

8 to the castle

9 armour

10 mother love

11 a change of direction

12 prison

13 girls and boys

14 a wee deoch an doris

15 a call in the night

16 the full English

17 one last decision

Part Six

1 the very worst

2 wheel of fire

3 singles

4 snapshots

5 wedding gifts

6 hi-yo, Silver!

7 gatecrashers

8 it is written

Part Seven

1 the end

2 really the end

Keep Reading

About Reginald Hill

Acclaim for The Death of Dalziel

By Reginald Hill

About the Publisher

Part One

Some talk of ALEXANDERAnd some of HERCULES;Of HECTOR…

Anon, ‘The British Grenadiers’

1 mill street

never much of a street

west—the old wool mill a prison block in dry blood brick its staring windows now blinded by boards its clatter and chatter a distant echo through white haired heads

east—six narrow houses under one weary roof huddling against the high embankment that arrows southern trains into the city’s northern heart

few passengers ever notice Mill Street

never much of a street

in winter’s depth a cold crevassespring and autumn much the same

but occasionallyon a still summer day

with sun soaring high in a cloudless skyMill Street becomesdesert canyon overbrimming with heat

2 two mutton pasties and analmond slice

At least it gives me an excuse for sweating, thought Peter Pascoe as he scuttled towards the shelter of the first of the two cars parked across the road from Number 3.

‘You hurt your back?’ asked Detective Superintendent Andy Dalziel as his DCI slumped to the pavement beside him.

‘Sorry?’ panted Pascoe.

‘You were moving funny.’

‘I was taking precautions.’

‘Oh aye? I’d stick to the tablets. What the hell are you doing here anyway? Bank Holiday’s been cancelled, has it? Or are you just bunking off from weeding the garden?’

‘In fact I was sunbathing in it. Then Paddy Ireland rang and said there was a siege situation and you were a bit short on specialist manpower so could I help.’

‘Specialist? Didn’t know you were a marksman.’

Pascoe took a deep breath and wondered what kind of grinning God defied His own laws by allowing Dalziel’s fleshy folds, swaddled in a three-piece suit, to look so cool, while his own spare frame, clad in cotton jeans and a Leeds United T-shirt, was generating more heat than PM’s Question Time.

‘I’ve been on a Negotiator’s Course, remember?’ he said.

‘Thought that were to help you talk to Ellie. What did yon fusspot really say?’

The Fat Man was no great fan of Inspector Ireland, who he averred put the three effs in officious. If you took your cue and pointed out that the word only contained two, he’d tell you what the third one stood for.

If you didn’t take your cue, he usually told you anyway.

Pascoe on the other hand was a master of diplomatic reticence.

‘Not a lot,’ he said.

What Ireland had actually said was, ‘Sorry to interrupt your day off, Pete, but I thought you should know. Report of an armed man on premises in Mill Street. Number 3.’

Then a pause as if anticipating a response.

The only response Pascoe felt like giving was, Why the hell have I been dragged off my hammock for this?

He said, ‘Paddy, I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but I’m off duty today. Bank Holiday, remember? And Andy drew the short straw. Not his idea you rang, is it?’

‘Definitely not. It’s just that Number 3’s a video rental, Oroc Video, Asian and Arab stuff mainly…’

A faint bell began to ring in Pascoe’s mind.

‘Hang on. Isn’t it CAT flagged?’

‘Hooray. There is someone in CID who actually reads directives,’ said Ireland with heavy sarcasm.

CAT was the Combined Anti-Terrorism unit in which Special Branch officers worked alongside MI5 operatives. They flagged people and places on a sliding scale, the lowest level being premises not meriting formal surveillance but around which any unusual activity should be noted and notified.

Number 3 Mill Street was at this bottom level.

Pascoe, not liking to feel reproved, said, ‘Are you trying to tell me there’s some kind of Intifada brewing in Mill Street?’

‘Well, no,’ said Ireland. ‘It’s just that when I passed on the report to Andy…’

‘Oh good. You have told him. So, apart from not feeling it necessary to bother me, what action has he taken?’

He tried to keep the irritation out of his voice, but not very hard.

Ireland said in a hurt tone, ‘He said he’d go along and take a look soon as he finished his meat pie. I reminded him that 3 Mill Street was flagged, in case he’d missed it. He yawned, not a pretty sight when he’s eating a meat pie. But when I told him I’d already followed procedure and called it in, he got abusive. So I left him to it.’

‘Very wise,’ said Pascoe, also yawning audibly. ‘So what’s the problem?’

‘The problem is that he’s just passed my office, yelling that he’s on his way to Mill Street so maybe I’ll be satisfied now that I’ve ruined his day.’

‘But you’re not?’

A deep intake of breath; then in a quietly controlled voice, ‘What I’m not satisfied is that the super is taking what could be a serious situation seriously. But of course I’m happy to leave it in the expert hands of CID. Sorry to have bothered you.’

The phone went down hard.

Pompous prat, thought Pascoe, setting off back to the garden to share his irritation with his wife. To his surprise she’d said thoughtfully, ‘Last time I saw Andy, he was going on about how bored he’s getting with the useless bastards running things. He sounded ripe for a bit of mischief. Maybe you ought to check this out, love, before he starts the next Gulf War single-handed. Half an hour wouldn’t harm.’

None of this did he care to reveal to Dalziel.

‘Not a lot,’ he repeated. ‘So perhaps you’d like to fill me in.’

‘Why not? Then you can shog off home. Being a clever bugger, you’ll likely know Number 3’s CAT flagged? Or did Ireland have to tell you too?’

‘No, but he did give me a shove,’ admitted Pascoe.

‘There you go,’ said Dalziel triumphantly. ‘Since the London bombings, them silly sods have put out more flags than we did on Coronation Day. Faintest sniff of a Middle East connection and they’re cocking their legs to lay down a marker.’

‘Yes, I did hear they wanted to flag the old Mecca Ballroom at Mirely!’

A reminiscent smile lit up Dalziel’s face, like moonlight on a mountain.

‘The Mirely Mecca,’ he said dreamily. ‘Had some good times there in the old days. There were this lass from Donny. Tottie Truman. Her tango could get you done for indecent behaviour—’

‘Yes, yes,’ interrupted Pascoe. ‘I’m sure she was a charming girl vertically or horizontally—’

‘Nay, ho’d on!’ interrupted the Fat Man in his turn. ‘You shouldn’t be so quick to put folk in boxes. It’s a bad habit of yours, that. Tottie weren’t just a bit of squashy flesh, tha knows. She had muscle too. By God, if they’d let women throw the hammer she’d have been a gold medallist! I once saw her chuck a wellie from halfway at a rugby club barbecue and it were still rising as it went over the posts. I thought of wedding her, but she got religion. Just think of the front row we could have bred!’

It was time to stop this trip down memory lane.

Pascoe said, ‘Very interesting. But perhaps we should concentrate on the situation in hand. Which is…?’

‘That’s the trouble with you youngsters,’ said Dalziel sadly. ‘No time to smell the flowers along the way. All right. Sit rep. Foot-patrol officer reported seeing a man in Number 3 with a gun. Passed on the info to a patrol car who called in for instructions. So here we are. What do you make of it so far?’

The Fat Man had moved into playful mode. It’s guessing-game time, thought Pascoe. Robbery in process? Hardly worth it in Mill Street, unless you were a particularly thick villain. This wasn’t the commercial hub of the city, just the far end of a very rusty spoke. The mill itself had a preservation order on it and there’d been talk of refurbishing it as an industrial Heritage Centre, but not even the Victorian Society had objected to the proposed demolition of the jerry-built terrace to make space for a car park.

The mill project, however, had run into difficulties over Lottery funding.

Right wingers said this was because it didn’t advantage handicapped lesbian asylum seekers; left wingers because it failed to subsidize the Treasury.

Whatever, plans to demolish the terrace had gone on hold.

The remaining residents had long been rehoused and, rather than have a decaying slum on their hands, the council encouraged small businesses in search of an address and office space to move in and give the buildings an occupied look. Most of these businesses proved as short-lived as the rathe primrose that forsaken dies, and the only survivors at present were Crofts & Wills, patent agents, at Number 6 and Oroc Video at Number 3.

All of which interesting historical analysis brought Pascoe no nearer to understanding what they were doing here.

Losing patience, he said, ‘OK, so there might be a man with a gun in there. I presume you’ve some strategy planned. Or are you going to rush him single-handed?’

‘Not now there’s two of us. But you always were a bugger for the subtle approach, so let’s start with that.’

So saying, the Fat Man rose to his feet, picked up a bullhorn from the bonnet of his car, put it to his lips and bellowed, ‘All right, we know you’re in there. We’ve got you surrounded. Come out with your hands up and no one will get hurt.’

He scratched himself under the armpit, then sat down again.

After a moment’s silence Pascoe said, ‘I can’t really believe you said that, sir.’

‘Why not? Used to say it all the time way back before all this negotiation crap.’

‘Did anyone ever come out?’

‘Not as I recall.’

Pascoe digested this then said, ‘You forgot the bit about throwing his gun out before he comes out with his hands up.’

‘No I didn’t,’ said Dalziel. ‘He might not have a gun and if he hasn’t, I don’t want him thinking we think he has, do I?’

‘I thought the foot patrol reported seeing a weapon? What was it? Shotgun? Handgun? And what was this putative gunman actually doing? Come on, Andy. I left a jug of home-made lemonade and a hammock to come here. What’s the sodding problem?’

Even diplomatic reticence had its limits.

‘The sodding problem?’ said the Fat Man. ‘Yon’s the sodding problem.’

He pointed toward the police patrol car parked a little way along from his own vehicle. Pascoe followed the finger.

And all became clear.

Almost out of sight, coiled around the rear wheel with all the latent menace of a piece of bacon rind, lay a familiar lanky figure.

‘Oh God. You don’t mean…?’

‘That’s right. Only contact with this gunman so far has been Constable Hector.’

Police Constable Hector is the albatross round Mid-Yorkshire Constabulary’s neck, the long-legged fly in its soup, the Wollemi pine in its outback, the coelacanth in its ocean depths. But his saving lack of grace is he never plumbs bottom. Beneath the lowest deep there’s always a lower deep, and he survives because, in that perverse way in which True Brits often manage to find triumph in disaster, Mid-Yorkshire Police Force have become proud of him. If ever talk flags in the Black Bull, someone just has to say, ‘Remember when Hector…’ and a couple of hours of happy reminiscence are guaranteed.

So, when Dalziel said, ‘Yon’s the sodding problem’, much was explained. But not all. Not by a long chalk.

‘So,’ continued Dalziel. ‘Question is, how to find out if Hector really saw a gun or not.’

‘Well,’ mused Pascoe. ‘I suppose we could expose him and see if he got shot.’

‘Brilliant!’ said Dalziel. ‘Makes me glad I paid for your education. HECTOR!’

‘For God’s sake, I was joking!’ exclaimed Pascoe as the lanky constable disentangled himself from the car wheel and began to crawl towards them.

‘I could do with a laugh,’ said Dalziel, smiling like a rusty radiator grill. ‘Hector, lad, what fettle? I’ve got a job for you if you feel up to it.’

‘Sir?’ said Hector hesitantly.

Pascoe wished he could feel that the hesitation demonstrated suspicion of the Fat Man’s intent, but he knew from experience it was the constable’s natural response to most forms of address from ‘Hello’ to ‘Help! I’m drowning!’ Prime it as much as you liked, the mighty engine of Hector’s mind always started cold, even when as now his hatless head was clearly very hot. A few weeks ago, he’d appeared with his skull cropped so close he made Bruce Willis look like Esau, prompting Dalziel to say, ‘I always thought tha’d be the death of me, Hec, but there’s no need to go around looking like the bugger!’

Now he looked at the smooth white skull, polished with sweat beneath the sun’s bright duster, shook his head sadly, and said, ‘Here’s what I want you to do, lad. All this hanging around’s fair clemmed me. You know Pat’s Pantry in Station Square? Never closes, doesn’t Pat. Pop round there and get me two mutton pasties and an almond slice. And a custard tart for Mr Pascoe. It’s his favourite. Can you remember all that?’

‘Yes, sir,’ said Hector, but showed no sign of moving off.

‘What are you waiting for?’ asked Dalziel. ‘Money up front, is that it? What happened to trust? All right, Mr Pascoe’ll pay you. I can’t be standing tret every time.’

Every tenth time would be nice, thought Pascoe as he put two one-pound coins on to Hector’s sweaty palms, where they lay like a dead man’s eyes.

‘If it’s more, Mr Dalziel will settle up,’ he said.

‘Yes, sir…but what about…him?’ muttered Hector, his gaze flicking to Number 3.

Poor sod’s terrified of being shot at, thought Pascoe.

‘Him?’ said Dalziel. ‘That’s what I like about you, Hector. Always thinking about other people.’

He stood up once more with the bullhorn.

‘You in the house. We’re just sending off to Pat’s Pantry for some grub and my lad wants to know if there’s owt you’d fancy. Pastie, mebbe? Or they do grand Eccles cakes.’

He paused, listened, then sat down again.

‘Don’t think he wants owt. But a nice thought. Does you credit. It’ll be noted.’

‘No sir,’ said Hector, fear making him bold. ‘What I meant was, if he sees me moving and thinks I’m a danger…’

‘Eh? Oh, I get you. He might take a shot at you. If he thinks you’re a danger.’

Dalziel scratched his nose thoughtfully. Pascoe avoided catching his eye.

‘Best thing,’ said the Fat Man finally, ‘is not to look dangerous. Stand up straight, chest out, shoulders back, and walk nice and slow, like you’ve got somewhere definite to go. That way, even if the bugger does shoot, chances are the bullet will pass clean through you without doing much harm. Off you go then.’

Up to this point, Pascoe had been convinced that the blind obedience to lunatic orders which had made the dreadful slaughter of the Great War possible had died with those millions. Now, watching Hector move slowly down the street like a man wading through water, he had his doubts.

Once Hector was out of sight, he relaxed against the side of the car and said, ‘OK, sir. Now either you tell me exactly what’s going on or I’m off back to my hammock.’

‘You mean you’d like to hear Hector’s tale? Why not? Once upon a time…’

Hector is that rarity in a modern police force, a permanent foot patrol, providing a useful statistic when anxious community groups press for the return of the old beat bobby. The truth is, whether behind the wheel or driving the driver to distraction from the passenger seat, a motorized Hector is lethal. On a bike he never reaches a speed to be dangerous, but his resemblance to a drunken giraffe, though contributing much to the mirth of Mid-Yorkshire, does little for the constabulary image.

So Hector plods; and, plodding along Mill Street that day, he’d heard a sound as he passed Number 3. ‘Like a cough,’ he said. ‘Or a rotten stick breaking. Or a tennis ball bouncing off a wall. Or a shot.’

The nearest Hector ever comes to precision is multiple-choice answers.

He tried the door. It opened. He stepped into the cool shade of the video shop. Behind the counter he saw two men. Asked for a description, he thought a while then said it was hard to see things clearly, coming as he had from bright sunlight into shadow, but it was his fairly firm opinion that one of them was ‘a sort of darkie’.

To the politically correct, this might have resonated as racist and been educed as evidence of Hector’s unsuitability for the job. To those who’d heard him describe a Christmas shoplifter wearing a Santa Claus outfit as ‘a little bloke, I think he had a moustache’, ‘a sort of darkie’ came close to being eidetic.

The second man (‘looked funny but probably not a darkie’ was Hector’s best shot here) seemed to be holding something in his right hand which might have been a gun, but it was hard to be sure because he was standing in the deepest shadow and the man lowered his hands out of sight behind the counter when he saw Hector.

Feeling the situation needed to be clarified, Hector said, ‘All right then?’

There had been a pause during which the two inmates looked at each other.

Then the sort-of-darkie replied, ‘Yes. We are all right.’

And Hector brought this illuminating exchange to a close by saying with an economy and symmetry that were almost beautiful, ‘All right then,’ and leaving.

Now he had a philosophical problem. Had there been an incident and should he report it? It didn’t take eternity to tease Hector out of thought; the space between now and tea-time could do the trick. So he was more than usually oblivious to his surroundings as he crossed to the opposite pavement with the result that he was almost knocked over by a passing patrol car. The driver, PC Joker Jennison, did an emergency stop then leaned out of his open window to express his doubts about Hector’s sanity.